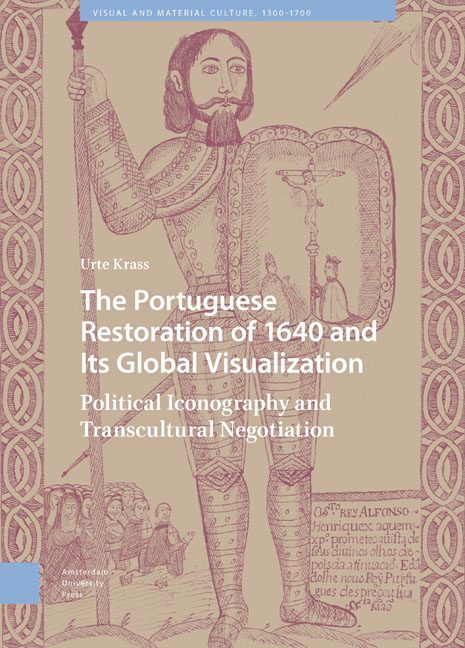

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

6 - Images in Diplomatic Service

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract: Among the first tasks of every newly installed ruler is having portraits of him- or herself made and distributed. The new Braganza king, however, had little chance of contracting first-class portraitists. The ambassadors who took royal portraits with them on their diplomatic missions abroad thus recognized these paintings’ virtue as being not in their high artistic quality, but in their ability to reveal truth about the person portrayed. The chapter traces the use of royal portraits and family trees on diplomatic missions to Paris, Rome, and London. The treatise Lusitania Liberata of 1645, presented to the English King Charles I, is then subjected to an in-depth analysis. Its engravings represent an ambitious attempt to reconceptualize Lusitanian iconography.

Keywords: royal portraits, Paris, Rome, England, Theatrum Europaeum, family trees, Lusitania Liberata

Portraits

Research on the theory of the Early Modern ruler portrait has shown that kings commissioned representations as one of their first acts upon taking office. The portrait was constitutive of that office: a real king was one who had been portrayed. As it happens, in the context of the reinstalled Lisbon court, little evidence has been preserved about the important task of commissioning official portraits. The portraits painted in the first years after John came to power can be counted on one hand; only two exist today, and these present a rather sobering picture of both artistic ability and possibility. The new king's portrait painters could not compete with the quality of the Spanish royal portraits; and the works do not reveal any iconographic or stylistic novelty.

This is understandable since during the Iberian Union, the production of portraits in Lisbon lay idle. During this period, high-ranking Portuguese nobility commissioned portraits of themselves and their families from Spanish painters. In Vila Viçosa, at the court of Duke John II—the future king—and his father, Teodósio II, painting was nevertheless consistently valued. In 1637, the Braganzas thus sent the painter Manuel Franco to Madrid to receive advanced training in the art of portraiture painting. Contemporary Italian painting was held in esteem and collected on grounds of prestige.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global VisualizationPolitical Iconography and Transcultural Negotiation, pp. 213 - 280Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023