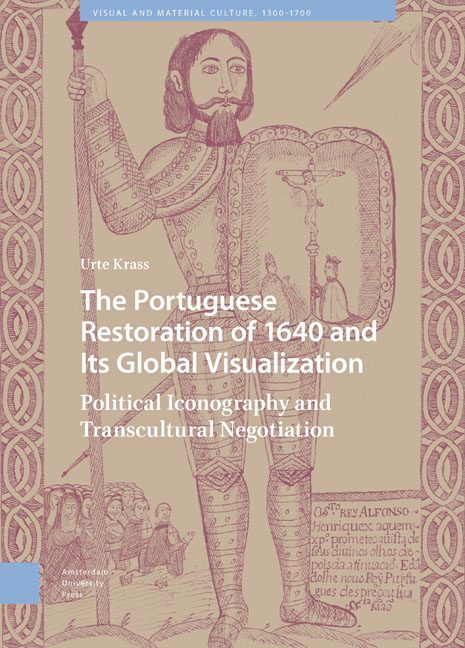

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization

The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global Visualization Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

1 - Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Signs, Miracles, and Conspiratorial Images

- 2 The Lisbon Miracle of the Crucifix (1 December 1640)

- 3 The New King’s Oath (15 December 1640)

- 4 Acclamations

- 5 Lisbon

- 6 Images in Diplomatic Service

- 7 The Imaculada as Portugal’s Patroness

- 8 The Funeral Apparatus of John IV (November 1656)

- 9 The Drawings in the Treatise of António de São Thiago (Goa 1659)

- 10 Ivory Good Shepherds as Visualizations of the Portuguese Restoration

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract: This chapter describes the system of signs, miracles, and images that existed in Portugal in the run-up to the revolt. Portuguese political providentialism is explained as a central component of the ideological framework of the Portuguese Restoration. A vital current that contributed to the events of 1640 was Sebastianism, the anticipated return of the last Avis king who allegedly had “disappeared” in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco. Linked to this belief was the movement of Bandarrism, which had its origins in a collection of verses composed by Gonçalo Anes Bandarra that were thought to have already pointed to the person of the Duke of Braganza as the new Portuguese king. The chapter discusses a sculpture in Alcobaça, a trove of ancient coins in Évora, as well as objects and images that might have served as conspirators’ “senhas.”

Keywords: Portuguese providentialism, Vision of Ourique, image miracles, clandestine image cultures, hidden Christians in Japan

Portugal 1640: National Identity, Providentialism

We will dive into the image worlds of the Portuguese Restoration by examining images that had a role in the run-up to the revolt. These were certain images woven into stories of miracles and others which we can assume were used for clandestine purposes by the coup's conspirators. A miracle-centered discourse formed the decisive ideological framework for images of the Restoration. This was true for autonomist texts appearing before 1640 and for legitimist texts that were published after the revolt. In both, Portugal was represented as an instrument of divine providence and the Portuguese as God's second chosen people. In its unwavering attempt to discern divine working in the temporal realm, Portugal was similar to other Early Modern empires. Strikingly, we also find comparable discourses in the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Empires. Nevertheless, in seventeenth-century Portugal, political providentialism interacted in a special way with the emergence of a national Portuguese identity. As we will see, the decisive aspect of this providentialism was its spread over a number of continents. It was present in both Portugal and the colonial territories, above all in Brazil and the Estado da Índia.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Portuguese Restoration of 1640 and Its Global VisualizationPolitical Iconography and Transcultural Negotiation, pp. 53 - 102Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023