True Weltanschauung

In 1942 the philosopher Arne Næss (1912–2009) decided to build something unusual: a tiny boxlike shed at the very peak of Hallingskarvet, which is one of the highest mountains in Norway. It was hard to construct so he mobilized his mountaineer friends to help with the job. Conquering mountaintops had been a chief passion in his life, and the decision to build a shed on the very summit came as a natural extension of his interests. The first attempt to build it failed. He envisioned the shed overhanging the abyss from the peak’s cliff with an entrance from below through a hatch in the floor, but this entailed a complicated and dangerous construction process. His friend Boss Walther died in the attempt to build this, and Næss decided to draw the shed back a bit to make it safer. When it was finished, he named it “Skarveredet” (“The mountain’s nest,” derived from what locals call “Skarven” – short for Hallingskarvet).Footnote 1 The only possible access to the shed is either by steep, almost impossible, hiking routes or by technical climbing. Skarveredet offers a secure place for climbers as protection from wind, rain, and snow. From the window the philosopher could look out on the world and truly think like a mountain. In his own words: “The only dignified way of life would be to remain on the mountain, not to descend. […] from here you have the proper perspective on the human being. The mountain is a symbol of the wide and deep perspective.”Footnote 2 Indeed, it is from this elevated, cold, and windy dwelling place he would later come up with the main principles of his ecophilosophy and environmental ethic of how to be good to the world.

From Skarveredet he would climb down to his somewhat larger cottage called Tvergastein, built in 1937 on a ledge directly below the shed. At this cottage, Næss explains, “I did all I could to educate myself to love everything here, to achieve the most love: the storms, the tiny flowers, the strong winds, and gray days.”Footnote 3 Næss hired some local mountain-peasants to build Tvergastein based on his own drawings. They worked extremely hard to carry no less than sixty-two loads of material to this remote location way above tree level. Two horses nearly died before a third horse managed to finish the job so that his mountaineer life could be satisfied. The larger cabin was for living and writing while Skarveredet was a climbing destination and a place for reflection.

Tvergastein was, along with Skarveredet, built to fulfill his desire for escaping from society into nature. The environmental philosophies of Næss and his followers, this chapter argues, reflected the periphery of this remote dwelling place, which offers an extraordinarily deep panoramic weltanschauung. Their reflections on the proper ethical relation between the individual and the environment are based on their experience of looking out on the scenery from this tiny shed. Their argument in environmental ethics about the importance of place, belonging, and identification with all species derives from their personal experience at Tvergastein and Skarveredet. Indeed, much of Næss’s later thinking around the balance of nature comes out of his experience of technical climbing, a sport where balance is everything.Footnote 4

Just less than a two-hour hike from Tvergastein, in the valley below, one finds a tourist resort called Ustaoset, where Næss used to get his supplies at the local grocery store. From its railroad station he would take a four-hour train ride to Oslo. At this resort, the well-heeled families of Norway enjoy a vacation spot with numerous weekend cottages supplied with electricity, roads, cars, and a monstrous hotel. The hotel was originally built in 1909 and, with its numerous additions, has evolved into a colossal cross-country ski-resort abode for the wealthy. Among those who enjoyed the hotel’s amenities was Næss’s close family, who had their own vacation cottage at Ustaoset. On his way down from Tvergastein, Næss walked past all these dwellings, which, to him, represented a shallow relationship with nature, and also the social milieu he sought to escape from.

Indeed, Næss was born in 1912 into a wealthy and well-known shipping family who provided him with a modest personal trust fund so that he could pursue his interests without economic worries. His early life can be understood as an attempt to run away from this background, and he succeeded fully in his escape at the age of twenty-five when he built Tvergastein so that he could have more time to enjoy nature and practice technical climbing.Footnote 5 He lived in his mountain home at Hallingskarvet for about ten years, and he would, for the rest of his life, continue to spend as much time as possible there. At the cabin he began gathering his own natural history collection of stones in order to emphasize the importance of science to himself and his visitors. Among them was his first wife Else (born Hertzberg, 1911–87). They went to the cabin on their honeymoon in the winter of 1937. Næss recalls:

We stayed for more than three months, and had storms we had never imagined were possible! … [T]he walls were just standing up into the air, and when we had the northern wind, the walls would bend so that when we had ink bottles, they would then rush all over the table. The wall was pushing the ink, the table, and the bottles all over. This was February, or March. And it looked as if – yes – the roof separated from the walls here, so you could look out onto the landscape. Hastily, I gathered all heavy things, and loaded down the roof so that it wouldn't collapse. If the roof had lifted just a little more, the wind would have taken all of it. We kept a heap of stones in the middle of the room here, so that if the roof went away, it wouldn't also take away the floor. We would hold onto all those stones, and try to somehow manage to live.Footnote 6

While holding on to the stones, Næss also worked on a regular basis as a philosopher at the University of Oslo. He explains in his own words: “I was made a full professor [in the autumn of 1939], with tremendous responsibilities. I managed to place all my responsibilities, including lectures, from Tuesday evening to before dinner Wednesday. So I could go by train to the mountains Wednesday and come back to the city on Tuesday the following week.”Footnote 7 In this way he made himself a sanctuary for serious thinking to evade the stress of administrative duties, teaching, debates, and polemics of the University. Consequently, Tvergastein soon attained a mythic status among Norwegian philosophers, since this is where they all had to travel to receive serious attention from their colleague or advisor. His cottage was a crucial tool in Næss’s self-fashioning as a sage, and, as a result, countless famous and not-so-famous celebrities, students, intellectuals, writers, and philosophers went on pilgrimages to the mountain guru.

Over the years they came home from the philosopher’s cabin with an almost endless stream of stories and anecdotes about the lively and eccentric professor, and some of these were noted down in mountaineering essays by his fellow technical climber, close friend, and student of philosophy Peter Wessel Zapffe (1899–1990). They were both prominent members of the Norwegian Alpine Club, which today regards them as their chief patrons. Conquering mountaintops was, until the early 1970s, their chief passion in life, and Næss’s closest friends were members of the Alpine Club. When Tvergastein was built, he was already the club’s most legendary member, having ascended 106 of the highest mountains in Norway before his eighteenth birthday. The club’s bon mot: “Climbing to other sports is like champagne to bock beer” – flaunted by Zapffe – captures the spirit of this upper crust fraternity. The club members, including Næss and Zapffe, would climb and conquer peaks, mostly in mountain-rich Norway. Having been at Skarveredet was a rite de passage for new club members, who were elected through a long and secretive vetting process.

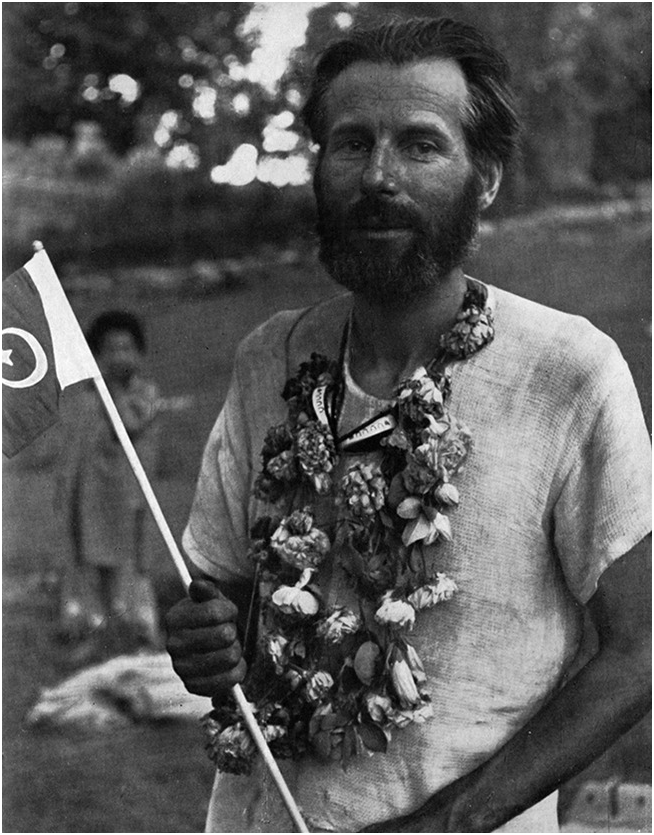

The Alpine Club would arrange challenging climbing vacations for its members at home and abroad. One of Næss’s most pleasurable climbing memories after the war was a trip to the north-west tribal region of Pakistan in 1950 (Figure 2). The Alpine Club organized the “expedition” so that its members could climb the mountain Tirich Mir and provide friends at home with thrilling accounts of how they, after much struggle, had managed to be the first climbers in the world to reach the top of this mountain. The Norwegian Geographical Society garnished the journey with some scientific activity by sponsoring the twenty-two-year-old botany student Per Wendelbo (1927–81), who later published an impressive study of the region’s flora.Footnote 8 Judging from the travel accounts, however, climbing was the all-dominating focus, besides participating in polo matches organized by local officials who went out their way to entertain the Norwegian tourists. In 1964 they repeated the success with another climbing vacation to Tirich Mir, which resulted in a book-length account of the achievement written by Næss. In it he would explain his ability to thrive as a technical climber as a mixture of pain and excitement in mathematical terms as T = G2/(LS + Ås) where T trivsel (thriving) equaled G2 glød i annen potens (excitement squared) divided by LS legemlige smerter (bodily pains) plus ÅS åndelige smerter (spiritual pains). The formula would later reemerge in his deep ecology inspired Ecosophy T, with the “T” being short for “thriving.”Footnote 9

Figure 2 Arne Næss on vacation with the Norwegian Alpine Club in Pakistan, 1950.

The Alpine Club and Næss’s mountaintop view suggests seeing both nature and society from above. Skarveredet and Tvergastein were located as far as possible from the social realm, yet close enough to suggest various household schemes for management of nature and society. The deep view from Skarveredet differs from the shallow view acquired by his family and their wealthy friends down in the valley bellow. Being situated above everybody else environmentally, socially, and intellectually resulted in a bipolar philosophy in which the good environmental life on the mountaintop and Tvergastein were juxtaposed with the evils of Ustaoset and urban life in general. This contrast would, as subsequent chapters will show, evolve in Næss’s and his friends’ thinking into a more general contrast between the clean and environmentally healthy Norway and a contaminated and unhealthy globe in need of Norwegian environmental wisdom. The high mountains represented what was clean, while the city was dirty and polluted, both literally and morally. Living simply on the mountain was crucial to the philosophers' aesthetic and moral image. Tvergastein served Næss and his ecophilosophy friends as a material representation and manifestation of a rich life with simple means. First among these friends was Zapffe.

The Last Messiah

“The mark of annihilation is written on thy brow. How long will ye mill about on the edge? But there is one victory and one crown, and one salvation and one answer: Know thy selves; be unfruitful and let there be peace on Earth after thy passing.” This was the dramatic conclusion in Zapffe’s essay, “The Last Messiah” (1933). Written in a poetic and somewhat archaic Norwegian, he argued that we humans are “a noble vase in which fate has planted an oak.”Footnote 10 As he saw it, humans are, with our ability to reason, the only species to be reflective enough to realize that the earth would be better off without us and that we consequently should be unfruitful and voluntarily cease to exist as a species. Our ability to reason was an accidental mutation gone wrong; it was an overdeveloped skill, and it made us unsuitable for our environment. As the earth will never satisfy human needs, hopes, and desires, we might as well leave it, instead of destroying it further. Or so was the revelation of the Earth’s last Messiah.

Zapffe’s deeply pessimistic view on the human condition was informed by a “biospheric” perspective he developed in the 1930s as a doctoral student of Næss. The result was Zapffe’s thesis, Om det tragiske (On the Tragic), published in 1941 when he was forty-two years old. Næss was, at the time, a full professor in philosophy, and only three years younger than his most talented student. Today Zapffe is almost unknown to the English-speaking community, but read by “everybody” in Norway. His works (sold in numerous editions) includes poems, philosophy, fairy tales, plays, and accounts from his mountaineering life. As an eminent storyteller, humorist, critic, iconoclast, and passionate environmentalist, his pessimist voice was taken seriously. Indeed, having read and marveled at his captivating essays was the secret handshake of environmental thinkers in Norway, who would rarely quote them but constantly reflect on them.

If one were not to follow Zapffe’s advice to be unfruitful and die out, what was then the human place in the environment? What was the human condition on Earth? Over the years, Zapffe himself would follow the various answers to such questions from ecologists, fellow philosophers, sociologists, and others from the academic sideline. He did not actively pursue university positions, but worked instead as an adjunct in philosophy. Yet, as an esteemed mountaineer, well-known technical climber, poetic writer, and environmentalist, he was the grandfather figure of philosophizing about nature. His argument – that we should leave Earth alone and die out – was not only the most radical, but also the best-articulated position in the room. And this was not a theoretical stand, as Zapffe refused to have children himself. He could not be ignored. As will be shown, Næss was greatly influenced by his student, as his thinking about ecology can be understood as an answer to Zapffe’s pessimism. Indeed, the history of Norwegian ecophilosophy can be understood as an ongoing reflection on how to address Zapffe’s arguments. The outdoor seminars at the remote Stetind Mountain in the north of Norway, which have been regular events since the mid-1960s, may serve as an example of this.

Though Zapffe certainly had a close circle of admirers among technical climbers in the 1930s, it was not until the late 1960s that his writings were canonized as required readings for outdoor enthusiasts, culminating with his 70th birthday in 1969. Compilations of his essays, a book-length philosophical introduction to his thinking, and a bestselling anthology about outdoor life entitled Barske glæder (Harsh Pleasures, 1969) would hit the bookstores. Using the metaphor of archeology, a reviewer in one of the nation’s largest newspapers noted that a “philosophical son of the wild [has been] dug up” by publishers from obscure and forgotten journals.Footnote 11 While the larger public would muse on Zapffe’s cunning reflections on the deeper meaning of sleeping bags, a new generation of young nature philosophers would take his academic work very seriously.Footnote 12 Two of them, to whom this chapter will turn shortly, were the philosopher Sigmund Kvaløy (1934–2014), who was the editor who “dug op” the essays in Barske glæder, and Nils Faarlund (b. 1937) who saluted Zapffe by asking: “Why waste your time on Marcuse and Habermas? Zapffe has already addressed the essential.”Footnote 13

First formulated in the early 1930s, Zapffe’s thinking can in its modus operandi be compared to Oswald Spengler’s Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West, 1918–23). By making analogies to the evolution of organisms, Spengler argued that the Western world had reached its last stage in life, and that the European civilization was at its decline. Zapffe would not make such sweeping generalizations about civilizations, but would place his pessimistic view of human future on a similar organismic footing. Næss was, while serving as his advisor in the late 1930s, committed to the Vienna school of positivism, and he consequently told Zapffe that he had to provide a scientific base for his thinking. Following this advice, Zapffe turned to Estonian-born German biologist Jakob von Uexküll’s work on the ways in which different species experience and react to their Umwelt (environment). In a similar manner, Zapffe analyzed the human condition within the environment and concluded that our “tragedy” was that our mental capacities made us overqualified to live in our Umwelt, the Earth.Footnote 14

In 1961 he restated his pessimistic stance on humanity in a “biosophic perspective” in which he would, for the first time in Norwegian philosophical debate, introduce ecology as one of the keys to understanding the human condition. The “survival of the fittest and the luckiest” captures well the biological drama of human life in the natural world, he argued. Yet the tragedy is that our inner metaphysical aspirations do not match our ecological condition.Footnote 15 The fact that our aspirations will never be satisfied on Earth, did not entitle us, Zapffe argued, to carry on with ecological destruction. Indeed, in the late 1950s he published what became some of the best-known – and certainly best articulated – prose in defense of nature conservation that exists in the Norwegian language. He wrote a very moving “funeral hymn” to the Gaustad Mountain, for example, when NATO built a trolley inside it for military purposes.Footnote 16 All of this made Zapffe the most prominent philosopher of nature and most famous advocate of nature conservation and outdoor life in the late 1960s. The fact that he operated outside academia made him even more attractive to a new generation of counterculture students suspicious of accredited philosophizing.

Zapffe and Næss were close friends as members of the Alpine Club, yet over time their friendship would run aground. They had different personalities: Zapffe was not particularly lighthearted, while Næss was playful and easygoing. “Sickness enters the body ‘by the kilo’ and has to be fought back ‘gram by gram’,” Zapffe would say, noting that “longstanding friendships often end because of a trifle.”Footnote 17 The “trifle” that ended their friendship was the fact that Næss would not endorse Zapffe’s book Den logiske sandkasse (The Logical Sandbox, 1966) for the syllabus for core courses in logic, and instead favored his own Endel elementære logiske emner (Some Elementary Logical Topics, 1941–75).Footnote 18 Having limited sources of income, Zapffe was in need of the royalties that Næss, in effect, denied him. This tension between them would place Zapffe in the margin of university life at the very moment that his thinking rose to the forefront of environmental philosophy and activism.

The Nation’s Philosopher

Næss was also marginalized in the late 1960s by a new generation of students engaged in social and environmental affairs. At the time he very much represented the older generation and the old way of doing things, and thus he felt he urgently needed to refashion himself as a philosopher of current affairs.

How did this come about? Back in the 1930s, Næss would not reflect on environmental issues. Instead, he devoted his thinking to epistemological and logical positivism. Before building Tvergastein, he had visited Vienna as a student to attend the famous logic seminar arranged by Moritz Schlick in the academic year of 1934/1935. He stayed in the city for fourteen months, and during this time he attended daily sessions of psychological therapy with Edward Hitschmann, a student of Sigmund Freud, as a part of a program to study psychology. Upon returning to Norway he went straight back to his parent’s cabin at Ustaoset where he wrote his PhD thesis on philosophy of science, which is clearly inspired by the Vienna Circle.Footnote 19 It got modest attention.Footnote 20 He then wrote a treatise on the meaning of the word “truth” as it was conceived of by those who are not professional philosophers, specifically based on semantic surveys of high-school students.Footnote 21 It was an untraditional way of pursuing philosophy, to say the least. Later in his life, the treatise would hurt his reputation, especially after Willard Van Orman Quine pointed to it as an example of “unimaginative” philosophy.Footnote 22

After finishing the treatise on truth, in the academic year of 1938/1939, Arne and Else Næss went to the University of California to study behaviorism with Edward C. Tolman. Arne recalls studying the psychology of rats by tracking their movements and behavior in specially made labyrinths. Though there is only evidence of him giving a philosophical lecture in Tolman’s archives,Footnote 23 Næss apparently worked on a manuscript about the rat experiments (which is lost) based on research he did with Kurt Lewin.Footnote 24 In any case, Næss returned to Norway as a behaviorist.

“I have learned as much from my rats as I have learned from Plato,” Næss told a competitor for the vacant position in philosophy at the University of Oslo, who had an interest in platonic metaphysics. The Platonist did not answer.Footnote 25 A debate arose at the time between those in favor of philosophy in the tradition of German geisteswissenschaft, and those who favored empirical philosophy inspired by the Vienna Circle. Of the three applicants Næss was the only empiricist, and, as the committee had a bias in that direction, he got the position at the young age of twenty-seven. His opponents saw his appointment as evidence of a problematic instrumental, material, rational, and reductive view of humanity taking hold on the field of philosophy.Footnote 26

With the onslaught of war, Næss became involved in the secret intelligence unit XU of the resistance movement, along with other science students, such as the radio-chemist Ivan Th. Rosenqvist and the botanist Eilif Dahl (discussed elsewhere in this book).Footnote 27 While working for XU, some of his students (who were involved in other aspects of the resistance) had to cover for him, by making it look as if he was working while he was actually out delivering secret documents. This, at least, could possibly explain why the book Oppgavesamling i logikk (Set of Exercises in Logic, 1942), written by one of his students, Mia Berner (1923–2009), was published with Næss’s name on the cover.Footnote 28 Whatever the motive, Næss would subsequently often get help from students in the production of teaching material and textbooks, thus blurring the boundary between authorship and assistantship.

After the war Næss published his major work Interpretation and Preciseness (1953), which became the foundation for the “Oslo group” in semantics, which, despite recognition at home,Footnote 29 failed to gain influence internationally due to a series of harsh reviews,Footnote 30 of which an evaluation by Benson Mates from the University of California, may serve as an example. A major point in Næss’s treatise was a formal procedure on how to generate precise interpretations of texts by developing alternative readings. Mates created a telling illustration of the procedure to readers of the prestigious Philosophical Review by using two interpretations of the statement “He yawned,” which were “He yawned voluntarily” and “He yawned involuntarily.”Footnote 31 The problem with Næss’s semantics was not that they were incorrect, but that they were boring.

Yet some people did find the Oslo group interesting, most notably the biologist Julian Huxley, who, in his capacity as the Director-General for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), hired Næss to study the semantics of the ambivalent word “democracy” as it was used in different political systems. It was an effort to find a unified language in a world of increasing bipolar Cold War tensions. Næss was, to Huxley, an example of a positivist philosopher who took science seriously. Under UNESCO’s patronage, and with the assistance of his student Stein Rokkan (1921–79), who later became a well-known sociologist, Næss consequently surveyed professors and leading intellectuals from around the world about the semantic meaning and different interpretations of the word “democracy.” The result was a fine contribution to objective political science about what democracy is while avoiding unscientific suggestions about what democracy should be.Footnote 32 To many delegates of the United Nations, it was rather shocking to read about Stalinism as one possible semantic interpretation of democracy, and despite a large amount of interest UNESCO never reprinted the report. To scholarly critics, the study and a follow-up done by the Oslo group were seen as “merely another useless addition to such compendia of semantic jiu-jitsu covering this field of definitions and re-definitions.”Footnote 33

Næss had more on his mind than semantic jiu-jitsu, which is apparent in his first popular philosophy book. Mahatma Gandhi’s teaching of non-violence came to the forefront of his thinking after his first visit to Pakistan with the Alpine Club in 1950. Back in Oslo he gave a lecture series about Gandhi’s political ethics, which resulted in a book co-authored with the young sociologist Johan Galtung (b. 1930), published in 1955.Footnote 34 Gandhi’s teachings, they argued, could be helpful in finding a peaceful transition away from the Cold War deadlock. In 1960 Næss followed up with a shorter version, which was translated into English and published as Gandhi and the Nuclear Age in 1965. Here he argued that people from the West had much to learn from Gandhi, given the threat of nuclear Armageddon. The book became Næss’s first international success with favorable reviews in academic as well as popular journals.Footnote 35 What was especially encouraging with Gandhi and the Nuclear Age was its appeal to young students. This was much welcomed, as his previously published books and articles had been generally ill received or ignored.Footnote 36

Næss also had to deal with the intellectual and social jiu-jitsu of teaching and maintaining the Examen philosophicum courses at the University. All students entering universities in Norway were required to take a preliminary set of core courses designed to introduce them to the academic culture and methodology, which meant studying logic and the history of philosophy for one semester. As higher education was (and still is) cost free in Norway, and as most studies were open to all, the chief social function of the tests was to filter out unsuitable candidates. Thus, for many, these tests would be their only academic experience. The tests have a rich history reaching back to the founding of the University of Oslo in 1811 and even further back to antecedents of preliminary exams of 1675 taken at the University of Copenhagen. Much of the identity of Norwegian academic life was built around these courses: they served as a model to other universities in the nation, as a demarcation of inclusion in and exclusion from academia, and would consequently cause a continuous stream of public debates.Footnote 37

The preliminary courses were important to the philosophers who put much energy into maintaining their social position. The courses were a key for recruitment of both students and faculty to the field, they meant employment opportunities for graduate students, and the syllabus provided the professors with healthy royalties from textbooks. Næss was in the focal point of these courses, as the only tenured professor in philosophy until 1967 (when the student of Quine, Dagfinn Føllesdal (b. 1932), was called upon and given a full professorship by the President of the University).

Næss was the author of a textbook on the history of philosophy and a textbook on logic, which were both required readings, not only in Oslo, but at most institutions of higher education in Norway.Footnote 38 These textbooks gave him a public persona as most scholars and students in Norway would read them at some point in their lives. Moreover, most students at the University of Oslo (with the exception of students in medicine) would have heard his lectures, usually given in the University’s largest auditorium. This gave him not only royalties (which he used to hire assistants), but also an important platform to spread his thinking. For at least three decades his philosophy of semantics and interpretations were part of the required curriculum and the subject of intricate exam questions for freshman students with absolutely no interest in the topic. Yet the art of semantic precession when providing an interpretation of a text was of paramount importance in order to stay on campus, as a forty percent failure rate on the exams was not uncommon.

With the number of students at the University of Oslo growing from about 6,000 in 1946 to more than 16,000 in 1970, teaching and managing Examen philosophicum became a daunting task for Næss and his growing cohort of teaching assistants and adjuncts. More and more time was spent in Oslo, and less and less in the mountains at his beloved Tvergastein. In his personal life, his wife, Else, had divorced him back in 1946. In 1955 he married the psychology student Siri (born Blom, 1927), which prevented him from seeing his children, but not from having to pay dependency allowances into the 1960s. His salary was a necessity to keep these commitments, though Siri became financially independent after her studies. By 1969 Næss was fifty-seven years old, had paid his family dues, and was craving the personal freedom and the simpler mountaineer life he had once had at Tvergastein. As a professor, “I am only functioning instead of living,” he said, and – to everyone’s surprise – he resigned.Footnote 39

Mastering the Mountains

His desire for freedom and longing for outdoor life was not the only reason Næss quit. When he signed his resignation letter in January he did not do so in his office, as it was occupied by radical leftists and followers of Mao. Indeed, the entire Department of Philosophy was in turmoil due to a weeklong occupation of all its facilities by students demanding a new curriculum, which in effect meant abandoning the syllabus arranged by Næss. He represented decidedly the old guard with his Vienna Circle-inspired philosophies of semantics, interpretations, definitions, and empiricisms. This was not an asset to students who thought of positivism as another word for the administrative nihilism they associated with the technocratic military complex of the Vietnam War.Footnote 40 Besides, technical climbing and bourgeois mountaineering did not prepare the mind for a revolution. If Næss wanted to leave his professorship, so much the better.

Not all the students would throw themselves upon the treasure troves of Lenin, Stalin, and Mao’s philosophies. Some of the more sophisticated criticism of Næss’s positivism began with the essay Objectivism and the study of man (1959) written by Hans Skjervheim (1926–99). In it he criticized the unity of science doctrine of logical empirisism from Næss’s early work, arguing that it led to a society in which nature, humans, and society could be treated as objects for social management.Footnote 41 In 1969 Skjervheim’s criticism of Næss was applied to environmental issues in a seminar, and he continued with a series of papers that later emerged in the anthology Vassdrag og samfunn (Watercourse and Society, 1971), edited by the ecologist Rolf Vik. Here Skjervheim would lash out against “technocratic politics” in which “one would plan and execute things over people’s heads” when implementing hydropower projects.Footnote 42 The young sociologist Øyvind Østerud (b. 1944) and the philosopher Gunnar Skirbekk (b. 1937) followed suit with similar criticisms.Footnote 43 To them hydropower politics illustrated the pitfalls of the managerial politics of power-socialism that emerged in the context of Næss’s positivist thinking. The fact that one possible interpretation of positivism would endorse hydropower development and exploitation of nature must have been a wakeup call to Næss, as he would soon agree with his critics.

Two people who were consistently loyal to Næss through this period were Sigmund Kvaløy and Nils Faarlund. Kvaløy was a thirty-five-year-old former student of Næss, who had grown up in the picturesque mountain village of Lom. He later moved to Eidsvold to attend high school, where he became friends with Faarlund, and he subsequently became an air mechanic for the Norwegian Air Force. His chief interests were philosophy and jazz, while he also, along with Næss, Zapffe, and Faarlund, pursued mountaineering interests as an active member of the Alpine Club and was a regular visitor at Tvergastein.

Faarlund was not a student of Næss but shared his interests. He had a graduate degree in engineering and biochemistry, and had been trained in landscape architecture and ecology in Hannover, Germany. As an active member of the Alpine Club he too had interests that drifted toward the field of philosophy. In 1967 he founded his own school, the Norwegian Mountaineering School, located in the mountain village of Hemsedal, while he also lectured in the art and practice of outdoor life at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences in Oslo from the time of its inauguration, in 1968, onwards. His lectures became legendary among environmentalists seeking a combination of philosophical training and practical experience in dealing with the wild, and his tiny Mountaineering School evolved into a hub for practical and philosophical reflections on how to live within the environment. Many of these reflections were published in the school’s journal Mestre fjellet (Mastering the Mountains, 1968–99), which was devoted mostly to cross-country skiing in the mountains, glacier hiking, and technical climbing. Faarlund was the chief editor and a regular contributor, and there were contributions from his outdoor-life friends and fellow alpinists, including his childhood friend Kvaløy, who would regularly contribute articles on the existential experience of wilderness while climbing, and the pitfalls of mass tourism.Footnote 44

Faarlund saw “outdoor life as a means to pursue scientific research,” and ecologists took him seriously by sending students – in need of courses in everything from tenting and outdoor cooking to survival strategies for harsh winter climates – to his school.Footnote 45 This type of knowledge was important for carrying out research in the field. Along with the practical know-how came an ethic of “using without consuming” nature and ecological reflections about the Earth being like a giant spaceship.Footnote 46 To Faarlund, being “outside” was actually being “inside,” as nature was the only true human home. Following this line of reasoning, he formulated his own philosophy of “free-air-life” of the “free-air-person,” thinking which inspired not only Næss, but the inner circle of Norway’s most devoted young mountaineers and environmentally concerned ecologists.Footnote 47

Kvaløy worked as an assistant to Næss in 1961, and he submitted an MA thesis under his supervision in 1965 on the philosophy of music communication. Both Næss and Kvaløy were passionate about music, the former of classical piano and the latter of jazz, which raised the question of how to “talk about music” within Næss’s philosophy of semantics.Footnote 48 Kvaløy’s thesis is decidedly an alternative piece of scholarship for which Zapffe’s biosophy would serve as the underlying methodology, while Kvaløy, at the same time, tried to be more empirical than his advisor. He would, for example, substitute page numbers with a metric system of measuring text. In any case, the thesis led to a lectureship in philosophy starting in 1967, and subsequently to a fellowship at the Institute of Biology where he would have his office next to the ecologist Ivar Mysterud, who became a close friend.Footnote 49 Mysterud would over the years engage not only Kvaløy but also Næss in numerous discussions. It was through these conversations that many of the Oslo philosophers and other non-biologists learned about ecological concepts and terms.

Though Næss had resigned in early 1969, for practical reasons he still had to remain in his position until the end of the year. However, he did not stay on campus. In his office he left Kvaløy in charge with “a pile of the Department’s letter-paper with Arne’s signatures – in the middle, further down, and at the bottom” so that Kvaløy could expedite things as he thought best.Footnote 50 He also left his seminar “Nature and Humans” in Kvaløy’s hands, which enabled Kvaløy to use Næss’s name as he saw fit and to organize the seminar according to his own mind.

Kvaløy did not stay put in the office, but instead invited Næss to drive what was known as the “Hippie Trail” from Oslo to Varanasi, along with Galtung in his Peugeot station wagon. As they left in January 1969, the trip marked Næss’s newfound freedom, while for Kvaløy and Galtung it was an attempt to heal the wounds inflicted by the students’ occupation of the Philosophy Department. Judging from Kvaløy’s charming flashback, the eighteen-day road trip undoubtedly created some of his very fondest memories.Footnote 51 Upon arrival in Varanasi, they celebrated Gandhi’s centenary with a month of peace researching at the Gandhi Institute. They then went on a vacation in Nepal, where they climbed to the top of the mountain Nagarkot, north of Katmandu, before flying back to Norway where Næss would continue to enjoy the mountains at Tvergastein. To Kvaløy the trip was like a “pilgrimage” to pristine beautiful mountains. He would, on his way home, travel through Iran and climb Mount Damavand together with Stein Jarving (1945–2005), who, taken with Kvaløy’s thinking, went home to found an ecologically inspired steady-state peasant community.Footnote 52

The Mardøla Demonstrations

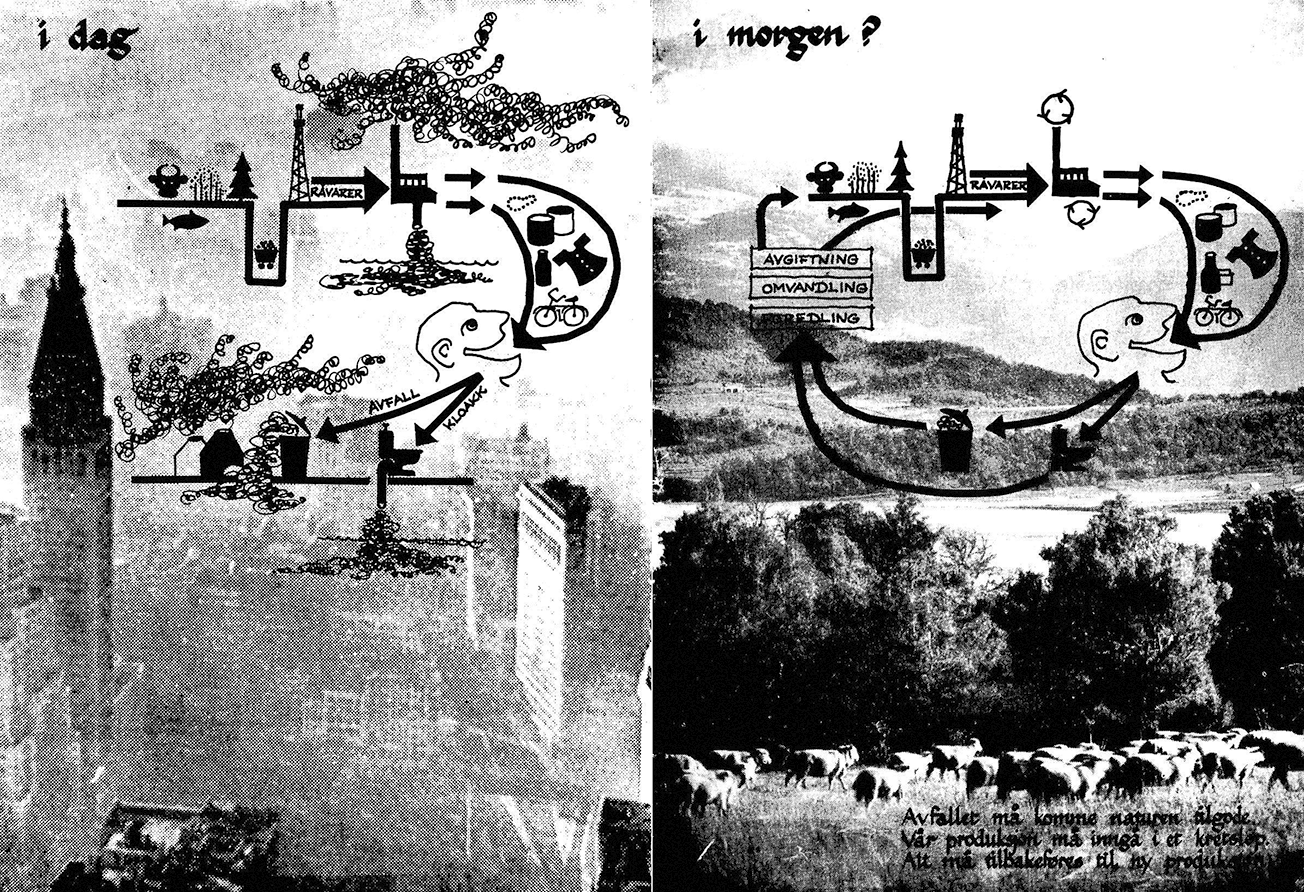

Upon his return to Oslo, Kvaløy saw the exhibition, Og etter oss … (And after us …), created by students of the Oslo School of Architecture in June 1969. They drew attention to the possibility of children “after us” having no environment to live in.Footnote 53 Built in specially designed tent structures and placed at the University Square at Karl Johansgate in the center of the city, it was seen by 80,000 people in Oslo alone. It was a travelling exhibition of ecological doom and gloom inspired by Vik’s popular writings about the eco-crisis and sponsored by the Norwegian Society for the Conservation of Nature.Footnote 54 With the help of dramatic graphic design, the architects crystallized a clear message about the world “after us” being either a disaster or a harmoniously balanced ecosystem. The self-sufficient ecological harmony of tomorrow was depicted as a remote picturesque Norwegian landscape, while the epicenter of environmental problems of today was at the Madison Square Park in New York City (Figure 3). This either/or dichotomy between the polluted city or the clean remote countryside, a future of industrial doom or ecological bliss,came to dominate the environmental debate in Norway thanks to Kvaløy and the emerging group of ecophilosophers.

Figure 3 Today (left) and tomorrow? (right). From the exhibition And after Us ... (1970) with the polluted society of New York to the left and the future ecological self-sufficient society in Norway to the right.

Kvaløy was very impressed with the exhibition, and invited the architects to join hands with students of ecology, philosophy, and members of the Alpine Club, to create Samarbeidsgruppa for natur- og miljøvern (Co-working Group for the Protection of Nature and the Environment), known in the English-speaking community as the Deep Ecologists. Those with a philosophical bent met at the Nature and Humans Seminar at the University of Oslo, which was a subsection of the association. In the fall semester of 1969 they turned Næss’s seminar into a hub for students and scholars who were both seeking deeper philosophical answers and questioning how humans should (and should not!) relate to the natural world. With the formal termination of Næss’s professorship at the end of the semester, they would continue to meet at the Department of Zoology where Ivar Mysterud worked. In the spring of 1970 they became known as the Ecophilosophy Group. Though the ecophilosophers were to have an equal say, Kvaløy would actually set the agenda of the seminar. His mountaineering interests from the Alpine Club would initially dominate with his philosophizing on the aesthetic and recreational quality of the environment in general, and mountains and waterfalls in particular. As a consequence, the historian of science Nils Roll-Hansen accused the ecophilosophers of favoring an “escape from the daily reality to the vacation paradise” of untouched nature.Footnote 55

Kvaløy and the Co-working Group quickly gained a significant following of students seeking radicalism within the acceptable socio-political boundaries of the Cold War. Soon the Co-Working Group grew into “Groups” as new subsections formed in Oslo, Bergen, and beyond. Ecophilosophy was not the only active group. Some chose to focus on coordinating the logistics of the broad-spanning association, while others chose to study hydropower and its alternatives, and others again chose to read aesthetics.Footnote 56 A significant number would gather to read Gandhi and study non-violence, inspired by Galtung and Næss’s book, and discuss whether or not direct action was a possible way to save pristine nature.Footnote 57 The groups were allied with neither the left nor the right, and thus were non-threatening in the bipolar political terrain. “What we stand for may seem archconservative and at the same time extremely radical,” Kvaløy argued. “We will therefore strike in both directions, and we will be attacked from all sides.”Footnote 58 They became an effective hard-hitting association attacking hydropower developments in particular.

The Co-working Groups were indeed “attacked from all sides” in their dramatic attempt to save the Mardøla river from hydropower development during the summer and early fall of 1970. The Mardøla Waterfall was Norway’s highest waterfall (and the 4th highest in the world). One of the activists, the technical climber and novelist Finn Alnæs, would climb up right beside the waterfall and take dramatic pictures of it, which he later published in a booklet.Footnote 59 Though the demonstrators had support from the neighborhood peasants who would lose their water, they got no sympathy from local workers in the neighboring valley, who could not care less about the waterfall and saw nature more as a resource for securing their jobs. They threatened the activists with violence and displayed banners, such as: “HIPPIES GO HOME – IF YOU HAVE ONE” and “TRY SOMETHING NEW – WHAT ABOUT A JOB?”Footnote 60 Most of the demonstrators had jobs. The underlying issue at stake was instead how to understand nature. Was it a resource to be used to secure jobs, a scenic place in which to enjoy country-life vacations, or an environment in which humans should learn to live in a different way? Thanks to well-organized Co-Working Groups, the demonstration evolved into a dramatic – yet still strictly non-violent – civil disobedience sit-in with more than 150 protesters blocking the construction site, followed by 50 journalists covering the story. In the end the demonstrators left voluntarily or, as in the case of Kvaløy and Næss, were carried away by the police. The whole event was made into an innovative documentary film, Kampen om Mardøla (The Battle for Mardøla, 1972), in which cameras were hand-held, creating a visual language of authenticity (as opposed to the official newsreels by the Norwegian national television).Footnote 61 For more than a decade the Mardøla demonstration was the defining event for environmentalism in Norway, in which taking a stand on this or other hydropower developments would distinguish friends from foes.

The demonstrators failed to save the waterfall, but managed to create an intense public debate around the nature of democracy and the importance of nature conservation. Though there were sympathies in the press for nature conservation, the confrontational mode of the Co-Working Groups caused general head shaking. There is not much of a tradition in Norway for civil disobedience, so this method of engaging the public became a topic of debate. One of the demonstrators, the philosopher Hjalmar Hegge (1920–2003), would take the lead, using much ink defending it as a way of protecting the nation against majority rule, technocratic bureaucracy, and the excesses of a representative democracy.Footnote 62 It is also clear from the press cuttings that the Co-Working Groups got either the credit or blame for what happened at Mardøla, and that Kvaløy was seen as the groups’ leader.

Perhaps the best articulated rhetorical defense of Kvaløy and the Co-Working Groups came from Zapffe and his wife Berit. In a long feature article, “At the Crossroad,” they would give “Sigmund Kvaløy and his collaborators our warmest thanks” for their heroic fight against “the moral pollution of government services with their bulldozer souls.” They then juxtaposed the defenders of nature’s “egenverdi” (inherent values) with those who were willing to sell the land so that we would all end up “chewing aluminum” (a chief product of hydropower electricity).Footnote 63 In their rage against hydropower, philosophical nuances were lost. With the question being whether or not to build a dam, the environmentalists got all the praise, while defenders of a dam were labeled in derogatory terms. This black and green way of thinking would, from now on, continue in the soon-to-be-written ecophilosophies of both Kvaløy and Næss. Kvaløy had edited Zapffe’s Barske glæder, he had used Zapffe’s biosophic perspective as a methodology in his master thesis, and he knew him personally through a common interest in technical climbing. Yet getting this kind of public endorsement from the old and much-respected philosopher, who was most certainly not known for scattering praise, must have been most heartwarming.

Næss did not participate in organizing the Mardøla demonstration, nor did he take much interest in environmental issues before the summer of 1970. He had published a short statement on the importance of creating a national park in 1965, and that was about it.Footnote 64 He was brought to Mardøla by Kvaløy in the last dramatic week of the demonstration, so that his fame in Norwegian intellectual life could bring momentum and attention to the cause (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Sigmund Kvaløy being taken away by the police at Mardøla, 1970.

A photo of the nation’s philosopher being taken away by the police was published twice in the press (and over time it has become perhaps the best known image of him) though only one journalist asked Næss questions while he was at Mardøla.Footnote 65 Instead it was Kvaløy who did most of the talking. Yet Næss’s sense of being involved with the young became a formative experience for him, given the occupation of the Department of Philosophy only one year earlier. He would, from now on, devote himself to the environmental cause, and thereby refashion himself as a philosopher of current affairs.

Unlike his resignation letter and newspaper interviews from 1969 – which are all about being liberated from the professional duties of a professor – he would now claim that he resigned so that he could devote himself to saving the environment. This, at least, is what he said on the book jacket of his next book, The Pluralist and Possibilist Aspect of the Scientific Enterprise (1972). His critics, who gave the book the most damaging reviews,Footnote 66 took it as an admission of philosophical failure: “Many philosophers have been led to the conclusion that philosophy is futile, but few have taken their own arguments seriously enough to act on them. On the book jacket we read that Arne Næss resigned from this Chair of Philosophy at Oslo in order to devote himself more fully to the urgent environmental problems facing man.”Footnote 67 Though it is true that Næss did not resign to devote himself to the environmental problems, in retrospect he probably wished he had or thought he had actually done so, as Næss after the summer of 1970 would spend the rest of his life thinking about the deeper meaning of ecology and spend his time arguing in favor of environmentalism. And he would pick up the philosophical ammunition to do so from the Ecophilosophy Group.

The Ecophilosophy Group

The Mardøla experience would energize and radicalize the philosophy students attending Næss’s former Nature and Humans Seminar. This was especially the case in the thinking of Kvaløy, the charismatic seminar leader. The fall of 1970 would prove to be their most active and productive semester. Why had they been unable to save the Mardøla waterfall? The majority of Norwegians were in favor of the hydropower development and opposed to the demonstrations. A survey from the time shows that fifty-seven percent of Norwegians thought the non-violent civil disobedience practiced at Mardøla was wrong.Footnote 68 Yet the activists thought they had done the right thing and that history would judge them differently. At the seminar it was time for soul searching.

The attendees were both students and faculty members with an interest in philosophy, and most of them had been at Mardøla that summer. Besides Kvaløy, Faarlund, and Næss, these participants included: Finn Alnæs, Reidar Eriksen, Per Garder, Jon Godal, Jon Grepstad, Hjalmar Hegge, Paul Hofseth, Oddmund Hollås, Karl Georg Høyer, Johan Marstrander, Ivar Mysterud, Sven Erik Skønberg, Ragnhild Sletelid, Svein Smelvær, Erna Stene, Arne Vinje, Jon Wetlesen, and probably many more.Footnote 69 Some of these attendees would, in subsequent years, shape Norwegian environmental academic, political, and bureaucratic institutions. At the seminar they read texts and discussed topics ranging from ecology to psychology of perception, social psychology, anthropology, nature philosophy, pedagogy, information theory, thermodynamics, and cybernetics. This was all done in an effort to understand the state of national and global environmental problems as revealed from the periphery of Mardøla.

The debate would gradually swing from aesthetic appreciation of scenic nature and waterfalls to broader ecological concerns about the harmony of nature as expressed by Mysterud and other ecologists. What started with reflections about the recreational quality of mountains would thus lead to social criticism concerning industrialism’s lack of steady-state and ecologically informed thinking about the human status within the environment. It was not a shift without tensions. In the end, broader eco-political ideas for a steady-state society came to dominate the discussion. The alternative vision that would gradually emerge was that of a self-supporting nation in equilibrium inspired by fishermen-peasants who had once lived in harmony with Mardøla’s ecological balance. This alternative nation could then be the model for the world to admire. The Western consumer society and mentality, along with population growth, was at the heart of the environmental problem, and life at Mardøla was the remedy.Footnote 70

Kvaløy would cast the Mardøla conflict as being that of a reckless industrial society destroying a harmonious nature. As he saw it, the natural ecological complexities of the environment were broken down by the industrial society, and the task of the environmentalist was to stop the process by non-violent means.Footnote 71 After the Mardøla experience, he adopted from ecology the idea that complex ecosystems are more robust than a simple one. Inspired by Herbert Marcuse, he argued that a complex human society would have a better chance of surviving the environmental crisis than the “one dimensional man” of the industrial society.Footnote 72 What living in an ecological steady-state society entailed was rather unclear, though it implied some sort of agrarian “green lung” away from industrial and urban pollution.Footnote 73

Despite his resignation, Næss would stay on campus in the fall of 1970 in order to participate in the seminar. This is evidence of Næss taking a sincere interest, as he was known to be impatient with long meetings. He was intrigued by the questioning of the way in which humans treat the environment, and began taking notes for a possible publication. The first result of this came in a short article in which he questioned the ethics of the Alpine Club, including the “conquest” of mountains.Footnote 74 Næss also kept his office on the condition that teaching assistants to the Examen philosophicum course also could use it. In the fall of 1970 one of them was the philosopher Thomas Krogh (b. 1946). He challenged Næss to rethink his philosophy of science, and he must have been quite successful at it, as Næss would, from then on, give up much of his positivist informed thinking and come to agree with his opponents.

This turnaround came about when Næss co-wrote a preliminary textbook about the philosophy of science with Krogh, which was meant for the University’s core courses. Krogh had Marxist sympathies and encouraged Næss to analyze the social relations of science, including “the dark sides of the gigantic science apparatus of our century.”Footnote 75 In working with Krogh, Næss was confronted with the writings of John Bernal and other socialist critics of the role of science in society. As a result he came to agree with the critiques that the good things science can do are overshadowed by an abuse of science, which has led and will lead to a dehumanized society and environmental degradation of the planet.

As an alternative, Krogh and Næss pointed to the way “a scientific field’s general ecology” or “ecosophy” addressed environmental problems in an interdisciplinary fashion, as “ecosophy” was understood by Wetlesen (at the time a graduate student of Næss and attendee of the seminar).Footnote 76 Unfortunately, there is no other record of what Wetlesen meant by “ecosophy” in what is probably the first appearance of this term in Norwegian (and international) literature. Næss would soon adopt it as his own term in formulating his own environmental ethic. Krogh and Næss argued that the ecological sciences could offer a constructive alternative to the pitfalls of its competing disciplines. “We are all ‘thrown into’ our cosmic, social and individual existence,” they noted. “It is impossible to resign from the ecological context.”Footnote 77 Thus, it was imperative to develop a new interdisciplinary mode of research that addressed shared ecological needs and existence.

By the spring semester of 1971, the Nature and Humans Seminar was simply known as the Ecophilosophy Group. According to Mysterud’s recollections, Næss was one of the few who took notes at the meetings, and he would transform them into a couple of lectures entitled Økologi og filosofi 1 (Ecology and Philosophy 1), which he gave at the Student Association’s meeting at the University of Tromsø in May the same year. In them he introduced, for the first time, his “ecosophy”:

[It is] a type of philosophy, which takes an identification with all life as its point of departure in this life-giving environment. It establishes in a way a classless society within the entire biosphere, a democracy in which we can talk about a justice not only for humans, but also for animals, plants, and minerals. And life will not be conceived as an antagonism to death, but as being in interaction with surroundings, the life-giving environment. This represents a very strong emphasis on everything hanging together and the idea that we are only fragments – not even parts.Footnote 78

The eco-centric notion of humans as fragments of a larger whole was inspired not only by the ecological view of species as fragments in nature’s energy-circulation patterns, but also by Chinese social philosophy. The politics of Mao were popular with those young philosophers who had occupied Næss’s former department, and Mao’s collected poetry had just been translated into Norwegian. They include a rich body of metaphors concerning nature’s harmony, which caught Næss’s attention. Mao’s poem “In Praise of the Winter Plum Blossom” may serve as an example:

Næss would read this as an analogy of the individual’s relationship to society and the ecosystem. In China, he claimed, “the human being is not in the foreground, but instead an entire ‘ecological system,’ in which humans take part as fragments. Mao has perhaps kept a part of the classical Chinese outlook. In his political poetry, animals, plants, minerals, and landscape elements have a place that seems ludicrous to rough Western observers.”Footnote 80 The harmony of nature Mao endorsed, it is worth noting, was tough on both nature and humans, treating them indeed as fragments. Yet Næss would, like many of his contemporaries, fail to see this. Eager to gain acceptance, he wrote a sympathetic booklet about Mao, and included Mao’s thinking in a revised edition of his history of philosophy textbook in which he went out of his way to appeal to young radicals, as it was required reading for all the students at the University. The textbook had, for a while, a portrait of Mao on its front cover.Footnote 81

Næss’s adaptation of Mao’s thinking should be understood as an opportunistic attempt to gain acceptance among students and not as a sincere endorsement of Maoism. Moreover, the Mao quotes are taken from a first “preliminary edition” that in its physical shape looks more like a manuscript for circulation within the Ecophilosophy Group than a real publication. Though there are some references to Barry Commoner and Paul Ehrlich, American nature philosophers such as Aldo Leopold are notably absent from the analysis and did not enter Norwegian ecophilosophical debate until the 1980s (as discussed in Chapter 9). Moreover, as will be argued in Chapter 4, by 1973, Mao would fade away from Næss’s ecophilosophical writings and would be replaced by Gandhi. Indeed, the academic year of 1970–71 was, for the ecophilosophers, a period of asking questions rather than coming up with well-thought-out and articulated answers. A comprehensive “eco-philosophy” addressing the environmental crisis, Kvaløy noted in his orientation to the seminar in May 1971, “has not yet been formulated.” It was still in “the sketching stage.”Footnote 82 That would soon change, as the next chapter will show, as the ecophilosophers and activists from Mardøla would formulate a platform for what was soon to become known as the Deep Ecology movement.