“A bang, I see a flash of light before I get hit in the air. So this is what’s at the end of life, I think, imagining myself being thrown into the air, how long I don’t know. Lying in the snow waiting for everything to end.”Footnote 1 The Sámi civil rights leader Niillas A. Somby survived, but lost his arm in his failed attempt to blow up the bridge leading to the construction site of the Alta-Kautokeino river power plant. It was March 1982 and the Supreme Court had just ruled that the development of the waterway was lawful. Both events were front-page news in all major newspapers. After being told he faced at least a decade in prison, Somby fled with his family to First Nations people in Canada, who helped them to hide and escape extradition to Norway. In hindsight, the explosion at the bridge was an act of desperation, reflecting the breaking point of the bitterest Sámi civil rights and environmental conflicts in the nation’s history.

Somby was recovering in the hospital when Gro Harlem Brundtland, the Labor Party leader behind the decision to build the hydropower plant, was asked to chair the World Commission on Environment and Development. Wisely, she kept quiet about the invite as the timing was not right for the announcement of her as the United Nations’ voice for environmentalism and the interests of the Global South, including the rights of Indigenous people. Ten years later, in June 1992, Brundtland led a delegation of Norwegian environmental politicians to promote sustainable development at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (formally known as the UN Conference of Environment and Development). This chapter will discuss this decade and the ways in which Brundtland appropriated the Alta experience as Chair of the Commission. During the decade leading up to the Earth Summit in Rio, the Deep Ecologists became increasingly fundamentalist and politically irrelevant in Norway, while they also had their first international breakthrough in North America, thanks to the environmental organization Earth First! Yet the end of the Cold War in 1989, I argue, would lead to a shift away from Deep Ecological to global climatological perspectives. Propelled by the sentiment that capitalism had won over communism, Brundtland and her delegation to the Earth Summit would frame the solution to climate change in cost–benefit terms, rather than in socialist terms.Footnote 2

The Alta Demonstrations

In the late 1970s the Ecopolitical Cooperation Ring, the political arm of the Deep Ecologists, began organizing what became the most dramatic civil disobedience demonstration in post-war Norwegian history. In comparison, the events became as dramatic and poignant as the recent Dacota Access Pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in the USA. There is not enough space here to review the remarkable effort to save the Alta-Kautokeino waterway in the north of Norway from hydropower development. Fortunately, historians have already documented the remarkable events.Footnote 3 Shortly, after an application process that began in 1968, the Norwegian Parliament voted in 1978 in favor of the project, thanks to support from the Labor Party government with Gro Harlem Brundtland as Minister of Environmental Affairs. Key members of the Cooperation Ring were furious. “IS IT TIME FOR ANOTHER MARDØLA DEMONSTRATION?” they challenged.Footnote 4

The issue at stake was not only saving a truly pristine environment, but also protecting the civil rights of the Indigenous Sámi population who lived and worked in the Alta-Kautokeino canyon. The Sámi reminded the ecophilosophers of the Sherpa culture in Nepal they knew and idolized. The environmental future of the nation hung on this debate: should one build the hydropower project that would generate electricity for a consumer-capitalist society or should the river be preserved as an integral part of a steady-state society in harmony with nature? The events in Alta also became important in sending a message to the rest of the world, especially to the European Community, that it was possible to maintain and develop an ecological society free from the pitfalls of industrialism.

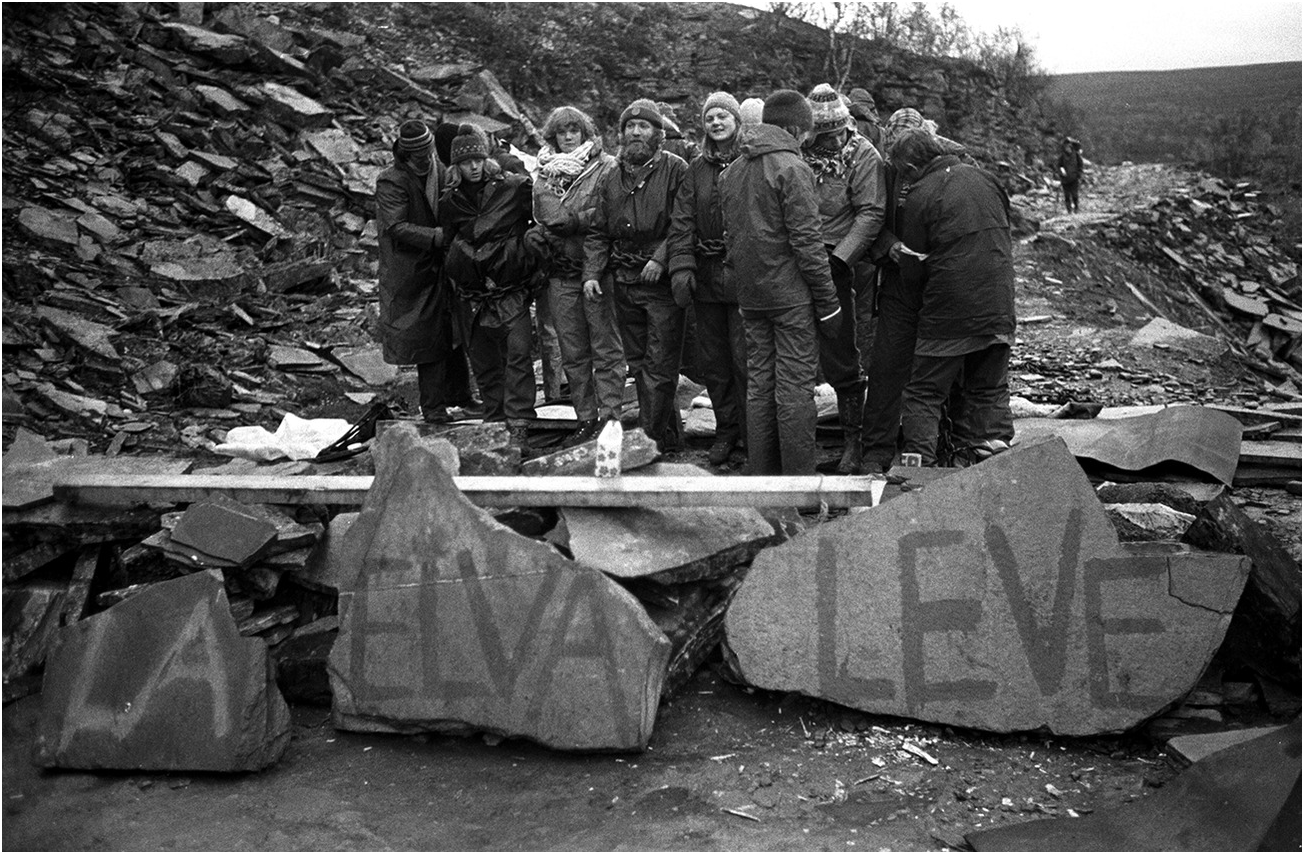

Though many people took on leadership roles in making the Alta demonstrations happen, Somby and Kvaløy became chief ideological spokespeople, respectively, on Sámi civil rights and environmental issues. Kvaløy had huge credibility among Deep Ecologists as the chief organizer of the earlier Mardøla demonstrations, along with his resistance to membership in the European Community. Hydropower or no hydropower, membership or no membership were the debates that divided friends from foes in Kvaløy’s world. Cast in a bipolar Cold War culture, his ecophilosophy came to reflect this either/or dichotomy. As a leading charismatic figure among the Deep Ecologists, Kvaløy framed the environmental debates throughout the 1970s in terms of what was either deep or shallow thinking. His ecophilosophy would boil down to a simple message: Do you support the “Industrial Growth Society” or the “Life Necessities Society”?Footnote 5 The Life Necessities Society was modeled on the lives of the Sherpa in the village of Beding in Nepal and also on the lives of the Sámi, while the Industrial Growth Society was the equivalent of membership in the European Community. The lack of philosophical subtleties in Kvaløy’s ecophilosophy was not a problem for the many demonstrators at Alta for whom the issue boiled down to whether or not they would build a hydropower dam there. Kvaløy coined their chief slogan: “La elva leve!” (Let the river live!), reflecting his ecophilosophy of letting the life force in nature flow (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Demonstrators blocking the road to the Alta hydropower construction site. The writing on the rocks reads “LA ELVA LEVE” (Let the river live). September 1979.

By the summer of 1979, demonstrators were in place blocking the road to the Alta-Kautokeino dam construction site, which they did until the fall of 1981 when the largest police operation in the nation’s history removed strictly non-violent but very determined demonstrators. For more than two years these events would occupy the country’s environmental and social debate, often as front-page news. The debates were no less intense at the universities as professors, as well as students, would leave their offices and classes to join the protestors.Footnote 6 Indeed, some classes were either suspended or ran at a minimum with substitution classes in ecophilosophy and ecology held instead on-site in Alta.Footnote 7 Yet, for all their efforts, the police operations put an effective end to the demonstrations. Frustrated with the situation, Kvaløy and a limited group within the Cooperation Ring contemplated sabotaging the construction as an alternative to protesting in order to halt the dam construction.Footnote 8 In February 1982 the Supreme Court ruled that the project for developing hydropower in the Alta-Kautokeino waterway was lawful, and the environmentalists gave up their cause, with the exception of Somby and two of his friends, who, in a last attempt to stop the dam, tried to blow up the bridge leading to the site. The Sámi and Deep Ecologists had lost, and Brundtland bore the majority of the blame for the disaster. As Minister for the Environment between 1974 and 1979 and subsequently Prime Minister from February to October 1981, she had wholeheartedly defended developing the waterway in the very heart of Sámi land.

The End of Deep Ecology in Norway

The defeat in Alta meant an end to Deep Ecology as a movement and intellectual endeavor in Norway. The failure to stop the hydro-dam construction caused much soul searching and bitterness among the Deep Ecologists.Footnote 9 Their vision for an alternative ecological steady-state nation had been held together by an ideological uniformity against industrial society, the European Community, and hydropower projects. When this shared vision for an alternative nation began to crack with the defeat in Alta, their arguments began to lose their relevance, students lost interest, and long loyal supporters began drifting away. This reflected a national trend. While twenty-five percent of Norwegian voters in 1977 had environmental issues as their top priority, the number had dropped to five percent by 1985.Footnote 10 As one Deep Ecologist noted about the early 1980s: “With the oil-age and the ‘YAP-period’ (Young Aspiring Professional) in Norway … the bottom fell out of the Norwegian commitment to nature-friendly lifestyles.”Footnote 11 At the institutional home of Deep Ecology, Environmental Studies at the University of Oslo, the students began voting with their feet as the numbers taking their courses would gradually drop. Those who stayed were advised not to seek a career as action researchers or ecologists, but instead find positions within the growing environmental bureaucracy.Footnote 12 When some students instead got research jobs in private biotechnology firms, a scholar at Environmental Studies asked: “Are the biologists selling their soul?”Footnote 13 His answer was yes. Among the Deep Ecologists there was time for self-examination. Had they in the midst of their efforts to save the environment forgotten to enjoy nature?Footnote 14

Some Deep Ecologists ended up drifting towards a less radical and more pragmatist position. At Environmental Studies there were seven full-time and ten to fifteen part-time employees, of which only their new leader, Ola Glesne, was tenured.Footnote 15 To keep the institution going under budget constraints, they established Stiftelsen miljøforskning (The Environmental Research Foundation) to avoid university bureaucratic red tape when accepting public and private research funds. They were following a general entrepreneurial trend in academia that enabled financial flexibility and at the same time established client relationships in research. The Foundation thus had the positive effect of keeping staff occupied with new projects and opportunities, while at the same time it drew attention away from the larger vision for an alternative nation. A report about the environmental virtue of flea markets for the Ministry of the Environment describing them as an “amusing trade in which everyone earns and nobody gets cheated,” may serve as an example.Footnote 16

For key Deep Ecologists the soul searching led to a hardening of their thinking, and the group’s core became increasingly fundamentalist. In the early 1980s Kvaløy inherited the farm Setreng at Singsås in Budalen, in South Trønderlag, from his uncle.Footnote 17 It is a charming old-fashioned farm that is steeped in history. He moved there and changed his name to Kvaløy Setreng to reflect a sense of the farm now being part of him. Anyone who wanted serious attention from the ecophilosopher would have to reeducate themselves and thereby forge a closer relationship with nature by working with him on the farm, if only for a couple of hours. Haymaking was a favorite. Eager to practice what he taught, Kvaløy Setreng made his farm into a Life Necessities Society showcase, complete with a tiny Buddhist temple a la Beding in Nepal. When staying in Oslo he lived in an apartment facing Bygdøy Allé, which at the time was one of the city’s worst streets in terms of pollution and heavy traffic. The contrast between the organic and industrial life could not have been starker and more personal. From his farm he would send a steady stream of warnings, to whoever would listen, about the immediate collapse of the industrial society. “[M]any will starve to death and kill each other,” he said in an interview with a magazine devoted to young environmentalists. Indeed, after the ecological collapse “a billion people will starve to death, and we will be forced to farm [potatoes] in Siberia.”Footnote 18 He also began substituting the Industrial Growth Society in his English lectures with “Advanced, Competitive, Industrial, Domination” using the acronym ACID.Footnote 19 His point was to focus on the destructive power of industrial society, which, like acid, would penetrate and destroy the organic Life Necessities Society.

To Kvaløy Setreng’s dismay, the village of Beding in Nepal, which had served as an idealized model in the 1970s for the future, changed – and not for the better. The power of ACID had arrived there in the form of tourism, roads, sanitation, and communication, all of which gradually brought Beding out of its harmonious state of ecological self-sufficiency. Disappointed, he turned his attention instead to Bhutan, at the time, an absolute monarchy largely closed to the rest of the world. To him, it was the world’s last bastion of ecological self-sufficiency in danger of being encroached upon by the ACID of the industrial world. Indeed, for the last part of his life Kvaløy Setreng would be a personal advisor to the young King of Bhutan, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, on how to make sure the country remained a true Life Necessities Society by promoting happiness in harmony with nature instead of capitalist consumption. In the role as the King’s advisor, Kvaløy Setreng would late in life find himself in heated debates about why people would flee from Bhutan due to the country’s human rights violations.Footnote 20

Kvaløy Setreng’s former teacher and fellow Deep Ecologist, Arne Næss, shared his admiration for life in Bhutan. In the late 1980s the country would for him also replace Nepal as the ideal state from which the world had to learn. For example, the country made sure its citizens would not drift into shallow ecological values after traveling abroad. Næss noted: “[In Bhutan] any students who go abroad for higher education must, immediately upon their return, spend six months travelling through the countryside for a re-education on the actual conditions and values of the people of their own country.”Footnote 21 Assuming that the students in question had learned what Næss termed a shallow ecological point of view, it meant that Bhutan used the power of the state rightfully in ordering their “re-education” after being contaminated by foreign universities. And Bhutan was not known for having a strong record when it came to human rights when forcing students to be reeducated in rural values.

Kvaløy Setreng was in favor of such reeducation policies as this reflected how he welcomed visitors at his farm, while Næss at heart was no such fundamentalist. Instead, Næss played with ideas, as his musings on Bhutan illustrate. The problem was that such ideas, whether or not they were to be taken entirely seriously, did not fascinate the young. The times were changing, and both ecophilosophers had lost touch with their followers, which dwindled in numbers. High-power introduction courses and textbooks in environmental ethics and ecology would not change this general trend.Footnote 22 Norway’s demographic was also shifting with the arrival of more immigrants. For Nina Witoszek, a refugee arriving in Norway after escaping communist Poland due to her translation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm and other underground publishing activities, Deep Ecology looked like an authoritarian peasant’s philosophy in its lack of appreciation of high-culture.Footnote 23 At the University of Trondheim and the University of Bergen, attempts were made to answer such criticisms and renew the ecophilosophical project by merging it with Karl-Otto Apel’s transcendental pragmatics.Footnote 24 While at the University of Oslo the last Deep Ecologists would seek refuge in the Department of Philosophy engaging in acute debates about the difference between “inherent” and “intrinsic” value in nature.Footnote 25 As important as such philosophizing may be, this thinking did not energize young environmentalists. As Næss later admitted, in Norway, Deep Ecology became “too narrow – [a] kind of sect.”Footnote 26

Deep Ecology Goes Global

While Deep Ecology dwindled away as an intellectual movement in Norway, Næss enjoyed an intellectual breakthrough internationally. The initial sign of this recognition came in an article by the American sociologist Bill Devall (1938–2009) entitled “The Deep Ecology Movement” (1980). It took Næss’s “Summary” from 1973 of his talk in Bucharest as a point of departure (see Chapter 4). In the same vein as Næss and additionally inspired by the historian of ecology Donald Worster, Devall would divide friends from foes by pointing to the legacy of “deep” thinkers, such as Aldo Leopold, Ernst F. Schumacher, George Sessions, Paul Shepard, and Gary Snyder, as opposed to “shallow” managerial ecology.Footnote 27 His article might have suffered the fate of most academic writings if it had not been for Dave Foreman who took Devall and Næss’s thinking to heart when he, in 1980, founded Earth First! The organization’s core principles stated: “Wilderness has a right to exist for its own sake. All life forms, from virus to the great whales, have an inherent and equal right to existence. Humankind is no greater than any other form of life and has no legitimate claim to dominate Earth.”Footnote 28 These principles became the backbone of a hard-hitting undercover organization that got much attention due to their military-styled radicalism and “ecotage” (as in “sabotage”). Devall and Sessions became the organization’s philosophers through the book Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered (1985). It not only endorses Earth First! but also lists the organization’s addresses around the world as places to go for readers interested in joining “deep ecology action groups.”Footnote 29 In the volume Næss is portrayed as Earth First!’s intellectual harbinger, and his Ecosophy T appears in its first English translation as an appendix at the end of the volume. This was all exciting for Næss, who had found a new audience willing to engage him. Indeed, inspired by these events, Alan R. Drengson started Trumpeter: Journal of Ecosophy (1983), a Canadian journal devoted to environmental philosophy in the spirit of Næss. At the time, there was only a limited amount of related material by Næss available in English. As a result, Næss began giving guest appearances in North America and published a string of articles on the topic for his new audience. The most important one was, perhaps, “Deep Ecology and Ultimate Premises” (1988), which laid out the core of his thinking. This included the widely distributed “A Platform for Deep Ecology,” which reflected and emulated Foreman’s “Statement of Principles” for Earth First!. Næss’s platform was published in The Ecologist, which portrayed him as “the father of the Deep Ecology movement.”Footnote 30

All the attention brought a series of mostly North American environmental philosophers to visit Næss at Environmental Studies in Oslo. Two of them included Peter Reed and David Rothenberg, who, in 1984, had just finished their undergraduate degrees, Rothenberg at Harvard University and Reed at Bowdoin College. Together with Esben Leifsen, they reestablished the Ecophilosophy Group, which had not been active for years. With self-designed stationary, they invited new recruits and reenergized former members. Næss was thrilled, and invited them along for philosophizing while mountaineering, climbing, skiing, and visiting Tvergastein. The result was a well-argued paper by Reed published after his unfortunate death (from an avalanche in Jotunheimen in 1987), and an equally elegant paper by Rothenberg suggesting a platform for Deep Ecology.Footnote 31 They both learned Norwegian in the process and set forth translating the reader for the Nature and Humans course, including Peter W. Zapffe’s poetic “Last Messiah” (1933), all of which appeared in English as Wisdom in the Open Air: The Norwegian Roots of Deep Ecology (1993).Footnote 32 While in Norway, Rothenberg also began translating Næss’s Økologi, Samfunn and Livsstil (Ecology, Community and Lifestyle, 1976), turning Næss’s dense idioms into elegant prose. When it appeared in 1989, it was an updated and revised volume relevant to the English-speaking audience and environmental affairs of the 1980s. Rothenberg also published a book-length interview with Næss, which is arguably the best introduction to his thinking.Footnote 33

As Earth First! grew in its radicalism in the 1980s, it came to erode the pluralism and non-violence prized by its parent philosophy. Earth First! took as its mission to defend the Earth from industrial society. It employed methods described in the group’s manual, Ecodefence (1985), which explains how to destroy defaulters’ bulldozers, puncture their car tyres, hack into the databases of their companies, return their executives' pollution to their own gardens, and use a sling to break the windows of people with environmentally destructive lifestyles.Footnote 34 Although professing pluralism and non-violence, the organization was run like a guerrilla group ready to destroy in order to prevent destruction. They were concerned about people, but the Earth came first. Some of Foreman’s followers became non-compromising ideologists using the Deep Ecology literature to promote ideas that were foreign to Næss. They concluded, for example, that draconian birth-control measures were necessary, and spoke of AIDS as a self-protective reaction of Earth against an overpopulated humanity.Footnote 35 They were not alone in these views. The founder of the Gaia theory, James Lovelock, who began engaging the Deep Ecologists in the early 1990s, wrote that humans were “like a disease” threatening to kill Gaia.Footnote 36 Soon Deep Ecologists found themselves in debates on whether mass starvation in Ethiopia was a good thing.Footnote 37

The direct association with Earth First! and their green rage made Næss and the Deep Ecologists vulnerable for criticism. After all, members of Earth First! were not inconsistent with his ecophilosophy in their radical approach to society and in arguing that AIDS and starvation could provide a long-term solution for the Earth.Footnote 38 The fact that most of the Deep Ecologists were men and that Earth First! had a military macho culture was questioned by an emerging group of eco-feminists. Perhaps the feminists were “deeper than deep ecology” with their gender-based social analysis?Footnote 39 Indeed, How Deep Is Deep Ecology? wondered another critic in a booklet from 1989, which questioned whether Næss had thought deeply enough about the structure of capitalism and possible Malthusian implications of this philosophy.Footnote 40 Næss also had to answer to a “third-world critique” of his ecophilosophy, despite his own self-understanding of being a stern supporter of the Global South.Footnote 41 Perhaps most damaging was the anarchist and social political theorist Murray Bookchin, who had a significant following within the US counterculture and beyond. He thought Foreman and the Deep Ecologists advanced “a ‘black hole’ of half-digested, ill-formed, and half-baked ideas … a bottomless pit in which vague notions and moods of all kinds can be sucked into the depths of an ideological toxic dump.”Footnote 42

As if the criticism from the feminists and social anarchists was not enough, in the mid-1980s, the animal liberation and rights activists also began questioning the Deep Ecologists. The specific issue at stake was Norwegian whaling. The dominating view in Norway was that whaling was an issue of resource management. Jørgen Randers, for example, argued in 1975 that, in order for the hunting “to be sustainable, one will have to keep the catch of whales below a certain annual quota securing their multiplication.”Footnote 43 Ten years later, the ecologist Arne Semb-Johansson and the physiologist Lars Walløe reiterated the argument, adding that there was a need for “a vigorous programme of research and monitoring.”Footnote 44 The Deep Ecologists, including Næss, had largely stayed away from the issue as whales were hunted by the rural fishermen-peasants they adored (see Chapter 1). Besides, they were, at heart, mountain climbers with a focus on the high altitude and not so much on what was going on in the ocean. Progressive young radicals were also generally in favor of whalers as they belonged to the idealized group of fishermen-peasants (see Chapter 1). Typically, when students in the early 1990s were served whale meat in the university cantina in Oslo, they would queue up in long lines for a plate in a show of support for whalers whose hunting the international environmentalists had tried to stop. It is telling that when the esteemed American environmental ethicist J. Baird Callicott visited Oslo in 1993 to lay out his well-thought-out criticisms of Norwegian whaling, he had to endure sitting next to an arrogant student of philosophy eating whale meat at a restaurant after his lecture.Footnote 45

International environmentalists were enraged by Norwegian hunting of minke whales in view of the nation’s grave history of hunting whales to the brink of extinction, and they began organizing boycotts of the nation’s seafood and tourism industry.Footnote 46 Greenpeace tried to stop commercial whaling, and the famed ocean activist Paul Watson and his Sea Shepherd organization went as far as to try to sink the whaling boat Nybræna in 1992. It was international news, and, according to a New York Times article, not of the type the “Green Queen” Prime Minister Brundtland preferred. “It’s a completely illogical, irrational wrongly-based campaign” against Norway, she argued, as “sustainable development” to her meant managing resources based on science, not emotions.Footnote 47 Most Norwegians would side with Brundtland who, in 1993, registered an objection with the International Whaling Commission’s ban on commercial whaling. The common sentiment in Norway was that killing minke whales was similar to that of butchering cows. It was a non-issue as long as the hunt was painless and minke whales were not endangered. Yet it was perfectly unclear how painful the hunt actually was to the whales, and even the closest associates of Brundtland had to admit scientific uncertainty with respect to estimations of whale populations,Footnote 48 with the joke being that it was like counting Russian submarines. Gradually, as a consequence of these debates, Næss would formulate an opinion against whale hunting, though he would endorse it if it could be proven to be healthy for the ecosystem (i.e. for reducing an overpopulation of whales).Footnote 49 These arguments focused on ecology and not the rights or welfare of individual whales. And this distinction was exactly what international animal rights and liberation activists found most troubling. Though whale defenders were unable to halt Norwegian hunting, they did manage to question the Deep Ecologists’ self-confidence of being the world’s environmental pioneers.

The situation was similar with respect to the yearly slaughtering of harp seal pups which was hardly questioned by the Norwegians discussed in this book, despite head-on resistance from Greenpeace and other international environmental organizations.Footnote 50 The Deep Ecologists would, in comparison, be more favorable to the protection of endangered animals such as wolves, beers, wolverines, and lynx, all of which rural farmers in Norway hunt with joy and determination to protect their oversized population of sheep. And these hunts were generally sanctioned and even financially supported by County or State environmental agencies. Næss and the ecologist Ivar Mysterud would defend both wolves and sheep in an article from 1987 in which they argued that both animals possessed intrinsic value as members of a “mixed community.”Footnote 51 They described the wolves in accordance with the Norwegian political ideal, namely as good social democrats within an ecocentric commune and that they should therefore be protected. Instead of a class/gender power struggle, they postulated a symbiosis of humans, animals, and plants – all of them guaranteed the right to self-realization. The ecocentric community was to be rational and yet compassionate, individualistic and yet ecological, creative and yet self-limiting. In effect, they proposed a utopian dream of Biblical proportions (in which “the wolf and the lamb shall graze together”Footnote 52) that overrode the individual rights and welfare of both animals, along with the interest of the rural farmers they idealized.

Næss enjoyed thoughtful criticism, and when he was attacked numerous scholars would rush to the defense of both him and Deep Ecology more generally. They argued that it was not a fundamentalist platform, but instead a respectable philosophy asking deeper questions about our relationship with the environment.Footnote 53 The Schumacher College founded in 1990 in the UK, for example, adopted Deep Ecology as its core message, along with the Gaia teachings of Lovelock. Yet the damage was done. The Deep Ecologists were somehow unable to shake off the image of them as raging Earth First!ers roaming the wilderness and carrying out ecotage. As Næss later confessed: “Dave Foreman had been a disaster for Deep Ecology.”Footnote 54

Our Common Future

If the Deep Ecologists were struggling after the Alta conflict, Gro Harlem Brundtland, the leader of the Labor Party, did not feel much better about how she had handled her decision. Indeed, many years later, she would look back at the events in Alta with regrets. By 1982 she had effectively won the battle, but had lost the larger war with the Sámi and the Deep Ecologists as she had lost face and credibility as defender of Indigenous rights and the environment. The Bravo oil spill of 1977 would still haunt her, as would the long vicious debate on how to handle acid rain (Chapter 8). The new conservative government that replaced her in the fall of 1981 would gleefully acknowledge the importance of national parks and point to the failures of callous technocratic planners and power-socialists within the Labor Party. She did not take these criticisms lightly.

The opportunity to recast herself as an environmentalist and champion of Indigenous rights came when Brundtland was asked to chair the World Commission on Environment and Development in March 1982. She was told by the Director of the United Nations Environment Programme that she was selected because she was the only person who had been both a Minister of the Environment and a Prime Minister.Footnote 55 In Oslo, she mustered a group of experts to whom she could turn for advice on how best to chair the Commission. The group included obvious choices like her former PhD advisor Walløe, the former Minister of Industry, Finn Lied, and the Labor Party’s former Deputy Director of the Planning Department in the Ministry of Finance and Professor of Law, Hans Christian Bugge. The long-time member of the Labor Party and ecologist Eilif Dahl (discussed in Chapter 2) was also on the list. More surprising was the choice of Paul Hofseth, the former leader of Environmental Studies who had been a stern opponent of the Alta power plant.Footnote 56 A conciliatory move by Brundtland, perhaps, or also a sign that the Deep Ecologist’ pragmatist leaning had taken hold.

There is no need to review the history of the Brundtland Commission here, as a recent thorough historical study has covered much of the material.Footnote 57 What is significant is that by the 1980s the vision for a “sustainable society” (as described in Chapter 7) began to have a life of its own outside Church circles. One early secular approach was the anthology The Sustainable Society: Implications for Limited Growth (1977), which does not refer to religious issues.Footnote 58 Lester Brown, the director of the Worldwatch Institute in Washington, introduced “the sustainable society” to a larger audience in 1981.Footnote 59 Around the same time, biologists began using the word “sustainability” as a descriptive term for factual processes in nature.Footnote 60 Reports by Brundtland’s patron, the United Nations Environment Programme, also used “sustainable development” as the guiding principle for nature conservation and environmental development in Africa in the early 1980s.Footnote 61 What is notable in these secular adaptations is that the longing for the Promised Land of harmonious sustainability as a resurrection of the lost Eden, remained. What Brundtland did when she made her opening speech for the Commission in Geneva in 1984 was to simply reinvigorate the terminology when arguing that “[p]olicy paths to sustainable development” were “a central concern.”Footnote 62 Humanity has to “meet … the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” as the World Commission would eventually come to define sustainable development in its final report.Footnote 63

Interestingly, in the same opening speech, Brundtland brought global warming to the forefront of the Commission. “Climatic changes induced by rising levels of carbon dioxide” could cause “massive economic and social consequences,” she argued.Footnote 64 The issue came to Brundtland and the World Commission’s attention in May 1984 through one of the World Resource Institute’s meetings, which provided a paper for policymaking on changing environmental conditions in the atmosphere, such as the depletion of the ozone layer, greater formations of acid rain, and accumulation of carbon dioxide.Footnote 65 As shown in Chapter 8, acid rain and atmospheric politics were familiar terrain for Brundtland, which she preferred discussing to the environment on the ground. Addressing acid rain had served her as a way of forging cooperation in Europe. “International Pact Sought on Acid Rain” was the headline in a newspaper announcing the creation of the “Brundtland Commission” in 1984, in which Brundtland told the press that the European agreement on acid rain “could become the basis for a global agreement” on also other climatic issues.Footnote 66 The branding of the Commission with her name was a way of building on her legacy of acid rain diplomacy. Perhaps the problem of climate change in a similar way as acid rain could facilitate world cooperation through the United Nations? Her attention to the issue of climatic change was reinforced through a written submission to the Commission’s public hearing in Ottawa in 1986 by the climatologist Kenneth Hare of Trinity College, Canada.Footnote 67 What caught Brundtland’s interest were not only the catastrophic consequences of climate change; ecological doom was old news to her, as Deep Ecologists for a decade had provided her with a stream of reports on the proximity of a civilizational collapse. Though she was genuinely concerned about ecological issues, the possibility of moving the environmental debate into the scientific domain of climatology was intriguing. Climate studies, it is worth noting, has deep traditions in Norway reaching back to the work of Vilhelm Bjerknes (1862–1951) and the Bergen School of Meteorology, which modernized the science of atmospheric weather and geophysics by the means of mathematical modeling and data analysis.Footnote 68 Norway also has a tradition of researching subjects relevant to understand climate change, such as glaciology, the movement of polar ice, and the storage of carbon dioxide in the ocean.Footnote 69 There was thus a scientific community in Norway ready to address global warming. Even more importantly, the politics of the atmosphere evoked a political regime that spoke to the patron of the Commission, the United Nations. In the narration of a global future in the Commission’s report, Cheryl Lousley notes, “imagine a world as if outside colonial histories and postcolonial contexts” and socio-political realities on the ground.Footnote 70 The problem of global warming had the potential of uniting the world through the United Nations, and the Commission’s final report, Our Common Future (1987), would thus spell out the dangers of climate change as one of the world’s chief environmental challenges.Footnote 71 And as a consequence, Brundtland and the Commission would initiate a process that led to the formation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1988, chaired by the Swedish professor in metrology Bert Bolin (1925–2007).

The World’s “Pioneer Country”

Brundtland received a half-hearted applause when she presented Our Common Future at home in 1987. The bitterness from Alta was still lingering among environmentalists during her second term as Prime Minister (1986–89). The rights and interests of Indigenous peoples had been mentioned several times in the World Commission’s report, and she would follow this up by establishing The Sámi Parliament of Norway for internal self-rule in 1989. Nevertheless, the fact that she would enjoy fame as an environmentalist abroad was understood among the Deep Ecologists as ironic, at best. They did not recognize her, in the words of international press, as a “Norse Goddess” who had successfully “managed to combine feminism and environmental concerns” at home.Footnote 72 And when she presented the report at Harvard University with the lecture “The Politics of Oil: A View from Norway,” in which she called for “a more equitable distribution of wealth” in the world, it was to the Deep Ecologists just plain political hypocrisy.Footnote 73 The initial reactions to Our Common Future among ecophilosophers were therefore to ignore Brundtland and assume that she had not been involved in the formulation of the report or in the writing of her Harvard lecture. Kvaløy Setreng, for example, did not mention her in his review of it, in which he argued that Our Common Future supported his own theories about the inevitable ecological collapse of the industrial world.Footnote 74 Similarly with Næss, who argued that “sustainability” was another word for ecological self-sufficiency he professed.Footnote 75 Brundtland, however, made it perfectly clear in the media that she, as Prime Minister, stood by the report, though few environmentalists took her seriously.

A top priority for Brundtland was to issue a white paper which would flatten criticisms at home that the Labor Party did not care about environmental issues. When the paper was sent for Parliamentary approval, Brundtland, as Prime Minster, put her full force behind it, determined to silence opponents and put both herself and the Labor Party on the environmental offensive. As was the tradition with Parliamentary papers, Miljø og utvikling (Environment and Development, 1989), as the white paper was entitled, had an anonymous author, though it was largely written by Hofseth and the biologist Peter Johan Schei under the guidance of the Ministry of the Environment.Footnote 76 At the core of the paper was a vision of Norway as “en pådriver” (“a driving force”) and “et foregangsland” (“a pioneer country”) for environmental change.Footnote 77 Norway was to show the world the path towards a sustainable society, a vision harboring back to Environmental Studies’ ecophilosophical idea of Norway being an alternative nation for the world to admire (see Chapter 5). The thought of Norway being a “pioneer country” also reflected the missionary longing that echoed the religious meaning of sustainability once provided by the World Council of Churches (see Chapter 7). Indeed, Brundtland would describe the ethos of the sustainability as “a religious belief.”Footnote 78 The white paper addressed a host of issues related to Our Common Future, such as the importance of protecting biodiversity, public transportation, financial support of developing countries, minimizing acid rain, ending ozone layer depletion, and protecting the oceans. It also promised to reorganize and strengthen Norway’s environmental agencies and, perhaps most exciting for the academic community, to increase research funds. Yet climatic change was at the forefront of Miljø og utvikling, labeled as “perhaps the most pressing environmental issue for the 1990s.” And Brundtland was determined to do something about it. She asked the Parliament to approve a policy that would “reduce the CO2 emissions so that they will be stabilized in the 1990s and in year 2000 at the latest.” Thereafter, the goal stated, the emissions were to “subside.”Footnote 79

The opposition naturally ridiculed the ambition as unnecessary and not founded on scientific facts, with the most vicious attacks coming from Ivan Rosenqvist, whom Brundtland, in 1977, had labeled a “ludicrous swindler” due to his views on the effects of acid rain (see Chapter 8). In 1989 he was shocked by the “ignorance, bluff, and partly dishonest use of data” among climatologists.Footnote 80 The underlying issue to him was not poor research, but how climate policies could undermine the industrialization of the nation and the production of petroleum. Rosenqvist had a captivating personality and a significant following. In his footsteps a series of prominent Norwegian scientists argued that anthropogenic climate change was a hoax.Footnote 81 This included a stinging critique of global warming research by the Nobel laureate in physics, Ivar Giæver,Footnote 82 as well as a plea for more “sobering talk” among climatologists from the same scientists who, back in 1972, had labeled acid rain researchers as “swindlers.”Footnote 83

To counter such claims, Brundtland initiated research programs and two new centers: the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), and a Center for International Climate Environmental Research, Oslo (CICERO). The task of these centers was to provide science to the politicians. They were to research how to realize the idea of “sustainable development” in Norway and beyond, and provide a path for how the nation could become the world’s “pioneer country” in this regard. Though officially independent, Labor Party environmental politics would in subtle and not-so-subtle ways frame research agendas at both centers. A portrait of Brundtland hung prominently in the meeting area of SUM (and is indeed still hanging at its Director’s office), for example, and the hands-on Chairman of its Board, Bugge, was one of her acolytes. Not only had he been one of her advisors for the World Commission, but, back in 1977, he was one of the principal authors of the Norwegian Official Report that vindicated Brundtland of any responsibility for the Bravo oil spill.Footnote 84

The Centre for Development and the Environment was not created from scratch, but instead absorbed Environmental Studies, which had been the bulwark of Deep Ecology scholar-activism since 1972 (see Chapter 5). As longtime opponents of Brundtland and her environmental policies, its researchers found this reorganization challenging. Soon tensions and disagreements emerged with respect to action research and the role of ecology in envisioning a sustainable future. Should the Center question the deeper foundations of society or simply (as Brundtland thought) generate ecological facts to be used at the political table? Unable to find a clear answer, environmental research at SUM became gradually marginalized by its Chairman. It is telling that when Reed and Rothenberg’s translation of the Nature and Humans Course Reader appeared in English in 1993, it was taken off the syllabus in Oslo. Instead of capitalizing on its growing international fame as the intellectual home of Deep Ecology, the Center that absorbed Environmental Studies sought to reinvent itself by focusing on developmental studies of the Global South. During this period, an aging Næss was the only scholar from Environmental Studies who stayed put in his office. To new scholars moving in, he was a charming emblem of the past with a ring of fame surrounding him, suitable for generating funds and public attention.

At the Center for International Climate Environmental Research the story was different.Footnote 85 Its first Chairman was Henrik Ager-Hanssen. He had served as Vice Chief Executive (and briefly as Acting Chief Executive) of the all-dominating, state-owned Norwegian oil company Statoil (“state oil”) for twenty-four years, and had just stepped down to be the company’s chief advisor on corporate greening. His role was to make sure that climate research at CICERO would not question or undermine Norway’s booming petroleum industry. Their first Director, Ted Hanisch, was a keen supporter of Brundtland, serving as her Parliamentary Secretary from 1986 to 1989. This close link to the Labor Party and Statoil was not accidental. The aim for CICERO was to envision a way forward where the ambitious Norwegian climate politics could exist in harmony with oil and gas exploitation. Typically, Hanisch would, in one of his first public appearances as CICERO’s Director, ridicule Næss and the Deep Ecologists for academic elitism and lack of understanding of the needs of ordinary people, all while avoiding a discussion on whether or not Norway would have to bring production of petroleum to a close due to climate change.Footnote 86

While these new research centers were in the process of establishing themselves, other large research programs began investigating climate change.Footnote 87 The Norwegian Research Council for Sciences and the Humanities (NAVF) and the European Science Foundation (ESF) arranged a large conference to kick start such research in Europe. It happened in the Norwegian city of Bergen in 1990 in the context of the Regional Conference addressing the World Commission’s Our Common Future. Most of Europe’s environmental ministers attended the meeting to prepare for the forthcoming 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Perhaps Europe’s environmental leaders could agree on a research path for climate change similar to the Acid Precipitation Program of the 1970s? Creating a coalition of European environmental ministers for sustainability was Brundtland’s ambition.Footnote 88 Politically, the conference was a disaster, as activists blocked the buses carrying the ministers on their way to the hotel. Ironically, the buses were supposed to showcase the excellent public transportation. The ministers were stuck for more than an hour, while the activists shouted “Bergen meeting talking and eating!,” after which the ministers had to run the gauntlet of activists in order to get to their meeting rooms. (The police did not intervene as they were settling scores with local politicians who had accused them of being too violent in an unrelated case.)

Among the 138 scientists attending the conference it was paramount to show that they were not only “talking and eating” but actually contributing. The result was a thick anthology, produced with great speed, in which climatic change was at the forefront. It included conclusions and recommendations for politicians preparing for Rio de Janiero, stating that climate change was real, and that the way forward was in the domain of international law, as well as “cost effective” financial initiatives designed to curb emissions of greenhouse gases.Footnote 89

A Sustainable Climate

All this was happening while Brundtland’s government was in opposition for about a year. The Labor Party would, however, regain power in the fall of 1990. For her third term as Prime Minister (1990–96), she appointed Thorbjørn Berntsen (b. 1935) as the new Minister of the Environment. Known by friends and foes as “The Slugger,” he was a man of action, and a clear sign that Brundtland was determined to reach her ambitious goal of making Norway into a pioneer country for the world by stabilizing the country’s climate emissions by the millennium. Yet the prospect of curbing the emissions that had looked reasonable in 1989 looked overambitious by 1990. What had changed was the gradual realization that emission reduction was not possible while Norway’s oil and gas production was, at the same time, dramatically increasing. How could one increase petroleum production and spur economic growth while at the same time reducing the emissions? Or, in the language of Our Common Future, how could one meet “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations?”

Brundtland appointed the leader of the Labor Party’s youth wing Jens Stoltenberg (b. 1959) to be the State Secretary at the Ministry of the Environment, and “The Slugger” delegated this difficult question to him. At the time, he was thirty-one years old and working for Statistics Norway. He had, back in 1985, completed his candidatus oeconomices degree which was specially designed for talented students of macroeconomics. What made the degree stand out was that its students could focus on economics for five years. The Department of Economics, it is worth noting, was the very jewel of the University of Oslo, having produced two former Nobel laureates and with an intense research tradition. It is a department from which historically most of Norway’s leading economic bureaucrats had emerged.

Despite their talents, the economists had, since the 1970s, hardly been a productive force with respect to environmental issues. With the Deep Ecologists framing the debate, economists were asked whether or not it was possible to put a monetary value on wilderness (it was not!), and how one could envision an alternative, non-growth, ecologically informed economy.Footnote 90 These were large questions, to which the economists provided few answers. Instead, economists tended to reduce environmental issues to the monetary value of natural resources.Footnote 91 Things were now changing with the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the general sentiment that capitalism had won over communism. Moreover, there was more of a tradition of mathematical modeling in climate research than in the life sciences, which may also, perhaps, explain why the economists rose to the podium with mathematical solutions to climate change. In any case, Stoltenberg saw in climatic change an opportunity to engage the macroeconomic tradition of the Labor Party with respect to environmental affairs.

Historically, the Department of Economics at the University of Oslo had been filled with dedicated leftists, with John Maynard Keynes as their protagonist and Milton Friedman as their antagonist. Stoltenberg was no exception to this trend. His degree thesis Makroøkonomisk planlegging under usikkerhet (Macroeconomic planning under uncertainty, 1985) was about developing an optimal plan for the nation’s future oil revenue. Today the thesis is widely accepted as the very architecture of what became the Government Pension Fund of Norway (known as the “oil fund”), which by 2011 evolved into the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, owning 1.3 percent of the world’s traded stocks and shares in addition to large portfolios of fixed-income investments and real estate.Footnote 92

In 1990, Stoltenberg knew what was worth knowing about the past, present, and future of Norway’s petroleum economy, and he was a keen proponent of exponential growth of its industry. He was also an outdoor enthusiast (an ardent hiker and cross-country skier), and he did not take environmental issues and climatic change lightly.Footnote 93 How could one nurture Norway’s oil and gas exploitation while at the same time curbing the world’s greenhouse gas emissions? Stoltenberg would bring the question to his former student friends and professors at the Department of Economics, while also including Hanisch and his colleagues from CICERO. Reflecting the end of the Cold War, a growing body of literature on environmental cost–benefit economics had emerged.Footnote 94 Drawing on the cost–benefit literature and inspired by the US emissions trading system for sulphur dioxide quotas, they came to the conclusion that the most cost-effective way of reducing greenhouse gases without having to curb oil production would be to introduce a similar system for Europe, and perhaps the entire world. With plenty of money from the oil, Norway could then buy such quotas and reach its millennium goal.

There was only one problem: One would first have to establish an emissions market supported by an international regime. Thanks to the remarkable political petroleum history by Gisle Andersen, Erik Martiniussen, Yngve Nilsen, and Anne Karin Sæther, there is now a viable account of what happened next.Footnote 95 In the years leading up to the Rio meeting, Norway engaged in an intense diplomatic campaign led by Stoltenberg’s father, Thorvald Stoltenberg, who was Brundtland’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. In keeping with the division of labor between scientists and politicians (suggested by Brundtland), the actual traveling was done by professional diplomats, mostly his Deputy Secretary Kåre Bryn assisted by Harald Dovland and Jostein Leiro. They were met with much resistance in European countries who argued that Norway should perhaps curb its own emissions instead of buying the achievement of others. The reception was not much better in newly industrialized countries such as India, Thailand, and Malaysia. When Brundtland traveled to Rio de Janeiro with her delegation to promote the idea, she too failed to convince the world about the virtue of carbon emissions trading. What was achieved was a Framework Convention on Climate Change that established a diplomatic way forward toward a 1997 meeting in Kyoto. The world’s delegates at the Earth Summit had widely diverse opinions about how to achieve sustainable development, and agreed, consequently, on a Convention on Biological Diversity.

Back in Oslo they realized that they would have to muster support from the Global South. Without these votes they would have no chance at getting acceptance for emission trading in the upcoming meeting in Kyoto. The following year Norwegian diplomats consequently spent time trying to convince the leaders of the world’s poorest nations about the value of carbon emissions trading. What they put forward was a system where a rich country would introduce a carbon-clean development initiative in a poor country and get credit for that in their carbon account at home. For example, if Norway installed solar cells in sunny Burkina Faso, they could get carbon emissions credit for the project in Norway. To prove their sincerity, Norway actually did install solar cells in Burkina Faso. Between 1992 and 1997 Norway undertook numerous projects like these, mostly in the Global South, mustering support for what would be called Clean Development Mechanism or CDM.

CDMs would mean business in Norway, as one of the nation’s more obscure industries is certifications provided by Det Norske Veritas (DNV), which is one of the three largest classification companies in the world (the others being Lloyd’s Register and the American Bureau of Shipping). With more than 10,000 employees, DNV is a voice to be reckoned with in a small nation. For them, the verification of emissions cuts, carbon equivalents, and the Clean Development Mechanisms paved the way for their employees to engage in environmentalism. Every CDM project would have to be researched and certified, and doing so meant corporate greening of a business closely associated with shipping and petroleum industries. Stoltenberg visited the DNV headquarters and promised jobs, and appeared in their intramural news bulletin. He would later take pride in having helped DNV to become the largest CDM certifier in the world, with about half of the global market certified through DNV. Though never a highly profitable business, DNV was a leader of such certifications until 2014 when the market for CDMs collapsed.Footnote 96

By 1997, Norway had secured a majority vote from the Global South with the help of CDM test projects, and Norwegian diplomats were confident when they arrived in Kyoto. In United Nations international agreements every vote is equal, whether you represent the United States or Antigua, Belize, and Guyana (the last three being allies of Norway). As a result, in Kyoto, countries committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. They could do so in different ways: at home, by trading carbon dioxide equivalent quotas, and by buying clean development mechanism certificates. Soon, the European Union established a market for emissions trading, and the certification industry began issuing purchasable CDMs based on projects mostly located in Asia and the Global South. As a significant buyer in these new markets, Norway could comply with the Kyoto protocols. Over the years, the purchasing of emission quotas and development certificates came at a significant financial cost.Footnote 97 Yet to understand this endeavor only in terms of economic efficiency would be to miss the point, as there is a long tradition for paying indulgences in a nation dominated by Christian moral codes. What was most important to the Labor Party environmentalists was to showcase Norway as a virtuous “pioneer country” to its own citizens and the world. Promoting “sustainable development” was, as this book has shown, a secular expression for a religious call to prepare the ground for the Promised Land. And it was all paid for by the very cause of climatic change – petroleum.