Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Vignette: Quin's dark archive

- Introduction: Ways in to Quin

- Vignette: A bedsit room of her own

- 1 Berg: Shifting Perspectives, Sticky Details

- Vignette: That same sea

- 2 Three: A Collage of Possibilities

- Vignette: ‘Have you tried it with three?’

- 3 Passages: Unstable Forms of Desire

- Vignette: Moving onwards

- 4 Tripticks: Impoverished Style as Cultural Critique

- Vignette: Breakdown, breakthrough

- 5 The Unmapped Country: Unravelling Stereotypes of Madness

- Afterword: Where Next?

- Bibliography

- Index

1 - Berg: Shifting Perspectives, Sticky Details

Published online by Cambridge University Press: aN Invalid Date NaN

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

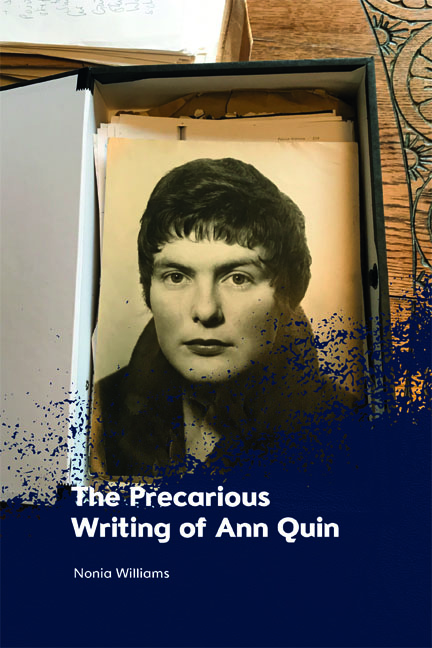

- Vignette: Quin's dark archive

- Introduction: Ways in to Quin

- Vignette: A bedsit room of her own

- 1 Berg: Shifting Perspectives, Sticky Details

- Vignette: That same sea

- 2 Three: A Collage of Possibilities

- Vignette: ‘Have you tried it with three?’

- 3 Passages: Unstable Forms of Desire

- Vignette: Moving onwards

- 4 Tripticks: Impoverished Style as Cultural Critique

- Vignette: Breakdown, breakthrough

- 5 The Unmapped Country: Unravelling Stereotypes of Madness

- Afterword: Where Next?

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Opening up Oedipus

A man called Berg, who changed his name to Greb, came to a seaside town intending to kill his father …

Many readings of Berg have attended to this superb opening. As Kate Zambreno puts it, ‘that first line of Berg, so stunning in its simplicity as to require its own page’. Danielle Dutton has remarked, ‘Rare enough is a book that begins by stating its intention’, and Dulan Barber, Quin's editor, claimed that this opening announces the ‘plot and essence’ of the book and is ‘incredibly well designed to lead the reader in and on’. The ‘intention’, or ‘plot and essence’ of the book are this: Aly Berg, disguised as Alistair Greb, and inspired by an anxious, uneasy desire to please his mother, Edith, tracks down his estranged father Nathaniel, moves into a bedsit room next door to the one occupied by Nathaniel and his lover Judith, and fantasises about patricide.

That Quin is reworking Oedipus – in terms of both the Greek play and the psychoanalytic ‘complex’ – is clear, and this offers one way in to reading Berg. As Barber rightly points out, though, ‘Berg is an uncompromising, a ferocious Oedipal statement. It is not a retelling of the Oedipal story.’ Quin's setting is an out-of-season ‘seaside town’, and the Oedipus story is subverted via a bawdy camped-up theatre of hair, make-up and character substitution. Take, for example, Berg as Greb. Reversing the letters of Berg's name so that the invented and inverted Greb takes his place means that its protagonist enters the text as an already parodic, back-to-front subject. The name ‘Greb’ is like a nonsense word, and the narrative plays with the idea of who the ‘real’ or ‘original’ version is, Berg or Greb, as well as whether the fantasised patricidal act would enable him to become his ‘real’ self. As Berg suspects, however, this is a world in which ‘not even the most indulgent of all actions “I shall kill” can make me declare “I am”’ (31). As this example suggests, and as my readings throughout this chapter show, Quin's brilliant and witty reimagining of Oedipus works to open up and deconstruct both the form and content of the story, to reimagine its triangular geometry, and to refuse closure and heteronormativity, retaining space for uncertainty and, as Loraine Morley puts it, ‘uninhibited exploration’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Precarious Writing of Ann Quin , pp. 25 - 51Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2023