Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Vignette: Quin's dark archive

- Introduction: Ways in to Quin

- Vignette: A bedsit room of her own

- 1 Berg: Shifting Perspectives, Sticky Details

- Vignette: That same sea

- 2 Three: A Collage of Possibilities

- Vignette: ‘Have you tried it with three?’

- 3 Passages: Unstable Forms of Desire

- Vignette: Moving onwards

- 4 Tripticks: Impoverished Style as Cultural Critique

- Vignette: Breakdown, breakthrough

- 5 The Unmapped Country: Unravelling Stereotypes of Madness

- Afterword: Where Next?

- Bibliography

- Index

Vignette: A bedsit room of her own

Published online by Cambridge University Press: aN Invalid Date NaN

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

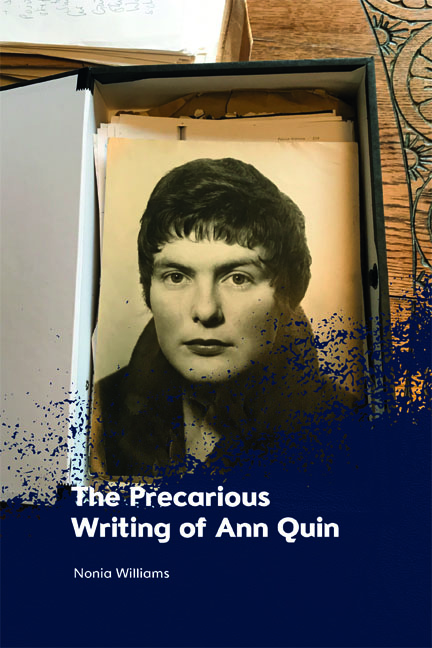

- Vignette: Quin's dark archive

- Introduction: Ways in to Quin

- Vignette: A bedsit room of her own

- 1 Berg: Shifting Perspectives, Sticky Details

- Vignette: That same sea

- 2 Three: A Collage of Possibilities

- Vignette: ‘Have you tried it with three?’

- 3 Passages: Unstable Forms of Desire

- Vignette: Moving onwards

- 4 Tripticks: Impoverished Style as Cultural Critique

- Vignette: Breakdown, breakthrough

- 5 The Unmapped Country: Unravelling Stereotypes of Madness

- Afterword: Where Next?

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Evenings spent in reading; half-heartedly doing homework, preferring to explore books discovered in the Public Library: Greek and Elizabethan dramatists. Dostoievsky (Crime and Punishment, and Virginia Woolf's The Waves made me aware of the possibilities in writing). Chekhov, Lawrence, Hardy, etc.

Quin, ‘Leaving School – XI’, p. 16Like Woolf, but in very different circumstances, Quin's literary education came more from library reading than formal schooling. In ‘Leaving School – XI’ (1966), she says she ‘sleepwalked through’ convent school years in Brighton, ‘More curious by what the nuns wore in bed. If they were really bald … than split infinitives’, ‘Amo, amas, amat’ and irregular verbs. The ‘possibilities in writing’ of ‘books discovered in the Public Library’ were far more inspiring, together with Saturday afternoons at ‘a seat in the Gods at the Theatre Royal’.

Except for a brief return to education in her late thirties, Quin's schooling ended in 1953, when she was seventeen. Her first job was as an assistant stage manager, where she wrote poems in her lunch breaks and dreamed of becoming an actor, while spending time gathering props, scrubbing the stage, sewing, making tea, laughing at ‘camp jokes I didn't understand’. But hopes of acting ended when nerves sabotaged an audition to RADA (Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), and Quin returned ‘to the world of books’ and to writing. She won a 10 shilling book token prize for her poem ‘The Lost Seagull’ and vowed: ‘I would be a writer: A poet.’ But without financial security, Quin was in desperate need of ‘a means towards bread and butter’, so she took a secretarial course and, ‘Armed with shorthand and typewriting certificates I went to a secretarial agency in London.’

From the mid-1950s to early 1960s, Quin was a secretary (and sometimes reader) in various legal, media and publishing offices, as well as at St Dunstan's in Brighton and the Royal College of Art in London, where she worked for three years. The year 1959 found her living in a room in Soho, working for a publishing firm during the day and writing her first novel, A Slice of the Moon, at night. Quin's living conditions at this time (and for much of her life) were precarious: as she put it, ‘The salary I earned was barely enough for rent and food.’

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Precarious Writing of Ann Quin , pp. 22 - 24Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2023