Book contents

- Princely Education in Early Modern Britain

- Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

- Princely Education in Early Modern Britain

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Book part

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 ‘Thys boke is myne’: how humanism changed the English royal schoolroom, 1422–1509

- Chapter 2 Chivalry, ambition andbonae litterae, 1509–1533

- Chapter 3 Erasmus’ Christian prince and Henry VIII’s royal supremacy

- Chapter 4 Educating Edward VI: from Erasmus and godly kingship to Machiavelli

- Chapter 5 Fortune’s wheel and the education of early modern British queens

- Chapter 6 Education and royal resistance: George Buchanan and James VI and I

- Chapter 7 Britain’s lost Renaissance? The Stuart princes

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

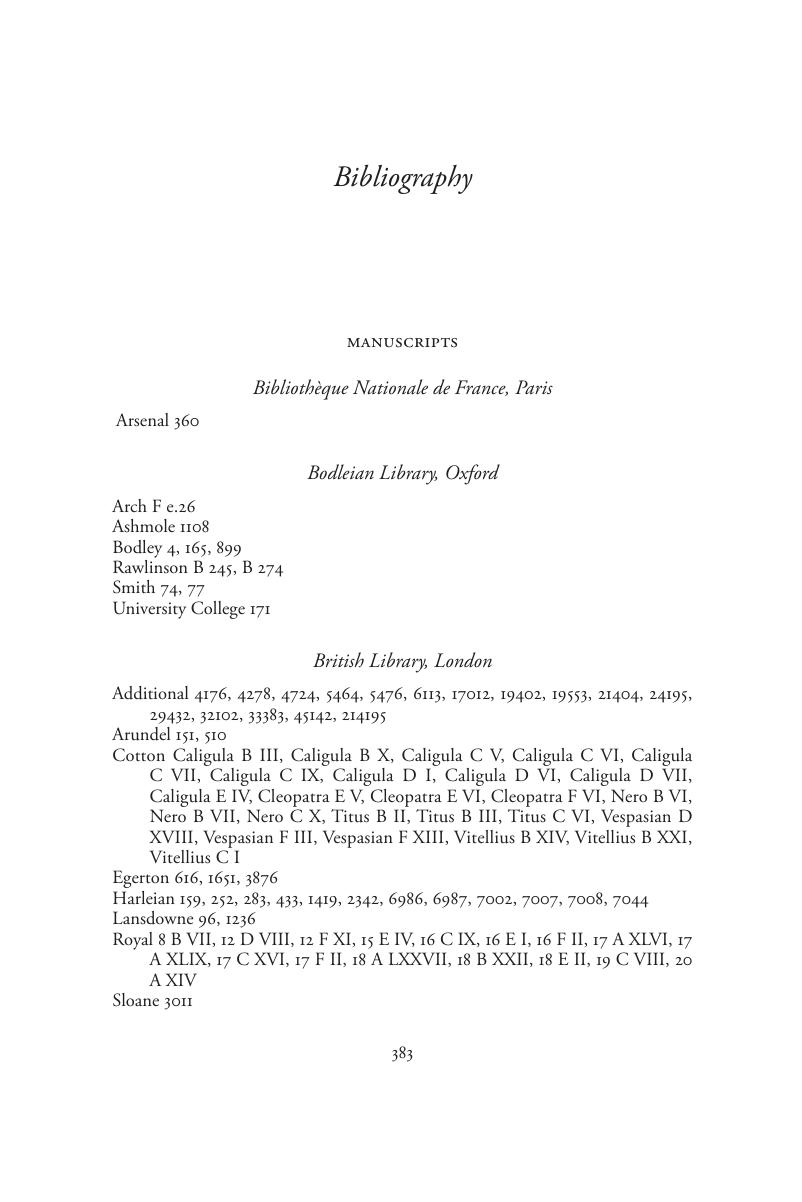

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2015

- Princely Education in Early Modern Britain

- Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

- Princely Education in Early Modern Britain

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Book part

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 ‘Thys boke is myne’: how humanism changed the English royal schoolroom, 1422–1509

- Chapter 2 Chivalry, ambition andbonae litterae, 1509–1533

- Chapter 3 Erasmus’ Christian prince and Henry VIII’s royal supremacy

- Chapter 4 Educating Edward VI: from Erasmus and godly kingship to Machiavelli

- Chapter 5 Fortune’s wheel and the education of early modern British queens

- Chapter 6 Education and royal resistance: George Buchanan and James VI and I

- Chapter 7 Britain’s lost Renaissance? The Stuart princes

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Princely Education in Early Modern Britain , pp. 383 - 431Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015