A disproportionate impact on health system performance

Private health insurance makes a small contribution to spending on health in most countries around the world, but its effect on health system performance can be surprisingly large owing to market failures and weaknesses in public policy. Because private health insurance can have a disproportionate impact, leading to risk segmentation, inequality and inefficiency, it should be considered and monitored with care.

Proponents of private health insurance fall into two camps. Some see private health insurance as attractive in its own right: in their view, a permanently mixed system of health financing will enhance efficiency and consumer choice. Others regard private health insurance as a second-best option in the context of fiscal constraints: not as desirable as public spending on health, but preferable to out-of-pocket payments. In richer countries, it is argued, encouraging the wealthy to pay more for health care or allowing public resources to focus on essential services will relieve pressure on government budgets (Reference Chollet and LewisChollet & Lewis, 1997). In poorer countries, private health insurance can play a transitional role, helping to boost pre-paid revenue and paving the way for public insurance institutions (Reference Sekhri and SavedoffSekhri & Savedoff, 2005). A key assumption in both contexts is that private health insurance will fill gaps in publicly financed health coverage, even though economic theory indicates that gaps may be filled for some people, but not for others. Analysts who acknowledge this tension suggest that it can be addressed through regulation (Reference Sekhri and SavedoffSekhri & Savedoff, 2005).

Evidence of international interest in private health insurance first emerged in the early 1990s, in work funded by the European Commission. Studies systematically analysing private health insurance in the European Union (Reference 40SchneiderSchneider, 1995; Reference Mossialos and ThomsonMossialos & Thomson, 2002; Reference Thomson and MossialosThomson & Mossialos, 2009) were later extended to cover other countries in Europe (Reference Thomson and KutzinThomson, 2010; Reference Sagan and ThomsonSagan & Thomson, 2016a, Reference Sagan and Thomson2016b). Comparative analysis of experience outside Europe began to appear from the late 1990s, with publications focusing on high-income countries (Reference JostJost, 2000; Reference Maynard, Dixon and MossialosMaynard & Dixon, 2002; OECD, 2004; Reference Wasem, Greß and OkmaWasem, Greß & Okma, 2004; Reference GechertGechert, 2010) as well as low- and middle-income countries (Reference Chollet and LewisChollet & Lewis, 1997; Reference Sekhri and SavedoffSekhri & Savedoff, 2005; Reference Drechsler and JüttingDrechsler & Jütting, 2005; Reference Preker, Scheffler and BassettPreker, Scheffler & Bassett, 2007).

This volume adds to comparative research by offering an analysis of private health insurance in 18 high- and middle-income countries globally, which together account for one third of the world’s population. It focuses on several of the world’s largest markets, both in terms of population coverage and contribution to spending on health; covers a range of different market roles; and includes countries in which private health insurance is the only form of health coverage for some people.

The chapters that follow are mainly single-country case studies based on a standard format to enable international comparison. Each case study examines the origins of a particular market for private health insurance, considers its development in the light of stakeholder interests and discusses its impact on the performance of the health system as a whole. Country case studies reflect national developments up to 2017.

By examining national successes, failures and challenges with private health insurance, the volume aims to:

identify contextual factors underpinning the emergence, evolution and regulation of private health insurance, including the role of internal and external stakeholders in influencing market development and public policy;

assess the performance of private health insurance against evaluative criteria such as financial protection, equity in access and use, efficiency and quality in service delivery, and contribution to relieving fiscal and other pressures on the health system; and

inform policy development in countries in different income groups.

The following sections of this chapter define private health insurance; outline market failures in voluntary health insurance and their consequences; summarize the history of and politics around the development of private health insurance, to understand how we got to where we are today; review data on the size of contemporary private health insurance markets; consider evidence on how well private health insurance performs; and draw policy lessons for countries seeking to introduce or extend the role of private health insurance or to minimize its adverse effects on health system performance.

No two markets for private health insurance are the same

Private health insurance is often defined as insurance that is taken up voluntarily and paid for privately, either by individuals or by employers on behalf of employees (Reference Mossialos and ThomsonMossialos & Thomson, 2002). This definition recognizes that private health insurance may be sold by a wide range of entities, both public and private in nature. It distinguishes voluntary from compulsory health insurance, which is important analytically because many of the market failures associated with health insurance only occur, or are much more likely to occur, when coverage is voluntary (Reference BarrBarr, 2004). The reference to private payment signals a further defining characteristic: private health insurance premiums are typically linked to a person’s risk of ill health or set as a flat rate, whereas pre-payment for publicly financed coverage is almost always linked to income.

The main focus of this volume is on voluntary private health insurance, defined in terms of the role it plays in relation to publicly financed coverage. Table 1.1 highlights four distinct roles and shows the countries in this volume in which they are present. Understanding the role private health insurance plays in a given context matters because role often influences the nature of public policy towards a market.

Table 1.1 Private health insurance (PHI) roles

| PHI role | Driver of demand for PHI | Main reason for having PHI | Country examples in this volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplementary | Perceptions about the quality and timeliness of publicly financed health services | Offers faster access to services, greater choice of health care provider or enhanced amenities | Australia, Brazil, Egypt, India, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Republic of Korea, South Africa, Switzerland, Taiwan, China |

| Complementary (services) | The scope of the publicly financed benefits package | Cover of services excluded from the publicly financed benefits package | Canada, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Switzerland |

| Complementary (user charges) | The existence of user charges (co-payments) for publicly financed health services | Cover of user charges (co-payments) for goods and services in the publicly financed benefits package | France |

| Substitutive | Rules around entitlement to publicly financed coverage | Covers people excluded from publicly financed coverage or allowed to choose between publicly and privately financed coverage | Chile; Egypt; Germany; the Netherlands before 2006; the United States |

Note: Markets often combine elements of the first two roles; some combine elements of the first three.

People buy supplementary private health insurance as a way of obtaining pre-paid access to private facilities, avoiding waiting times for publicly financed specialist treatment or benefiting from enhanced amenities in public facilities. Complementary private health insurance fills gaps that occur when the publicly financed benefits package is not comprehensive in scope or involves user charges (co-payments). In contrast to supplementary private health insurance and complementary private health insurance covering services, which can be found in many countries, complementary private health insurance covering user charges is much less widespread. People buy substitutive private health insurance because they are excluded from publicly financed coverage on grounds of age or income, or are allowed to choose between public and private coverage.

Three chapters in this volume focus on what the System of Health Accounts (OECD, Eurostat, WHO, 2017) refers to as compulsory private health insurance in the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States, included here as examples of the transition from voluntary to compulsory private health insurance. Parts of the private health insurance market in Chile, France and Germany are also classified as compulsory private health insurance in the System of Health Accounts. With the exception of Chile, private health insurance in these countries initially operated on a voluntary basis, played a significant role in the health system and became compulsory as part of a drive to extend coverage to the whole population, as described in Box 1.1. Chile has allowed the whole population to choose between public and private coverage since 1981; it is compulsory to be covered and everyone must contribute the same minimum share of their income towards coverage, regardless of which option they choose. Although the decision to opt for private rather than public coverage is voluntary in Chile and for higher earners aged under 55 years in Germany, substitutive private health insurance in these countries is classified as compulsory pre-payment in the System of Health Accounts.

Box 1.1 From voluntary to compulsory private health insurance in five countries

Health insurance in Switzerland has always been provided by private entities. In 1996, it became compulsory for the whole population for the first time. People pay premiums related to their risk of ill health to non-profit private insurers. People with low incomes receive subsidies from local government.

Publicly financed coverage became compulsory for lower earners in the Netherlands in 1941. Between 1941 and 1986, higher earners were allowed to choose between public and private coverage. In 1986, the richest third of the population was excluded from public coverage and relied on substitutive private health insurance. A national health insurance scheme was introduced in 2006. It is compulsory for all residents, operated by a mix of for-profit and non-profit private entities (former sickness funds and private insurers), governed under private law, extensively regulated by government and financed through a combination of flat-rate premiums, income-related contributions and subsidies for poor people.

In 1970, Germany allowed higher-earning employees to choose between public, private and no coverage; previously they had been excluded from publicly financed coverage. Since 1994, those who opt for substitutive private health insurance can no longer return to public coverage after the age of 65 years, lowered to 55 years in 2000, even if their earnings fall below the income threshold. In 2009, health insurance became compulsory for all residents. Those over 55 years old who had already opted for private coverage were no longer entitled to public coverage. Substitutive private health insurance is now their only source of coverage.

The Affordable Care Act introduced in the United States in 2014 made health insurance compulsory for people under the age of 65 years for the first time. Compulsory coverage provided by private insurers in return for risk-rated premiums now operates alongside publicly financed coverage for older people (Medicare) and poor people (Medicaid) introduced in 1965.

France allows private entities to cover user charges (co-payments) for publicly financed health services. By 2015, over 90% of the population was covered by complementary private health insurance covering co-payments. In 2016, it became compulsory for employers to provide this form of private health insurance for their employees. Employees now have compulsory private health insurance covering co-payments, while those who are not employed may have voluntary private health insurance covering co-payments.

Table 1.2 presents information on health spending in the 18 countries in 2017, the most recent year for which internationally comparable data are available.

Market failures lead to risk segmentation, inequality and inefficiency

Market failures in health insurance are well established (Reference BarrBarr, 1992). Economic theory posits that voluntary forms of health insurance will only result in an optimally efficient allocation of health care resources if certain assumptions hold: the probabilities of becoming ill are less than one (no pre-existing conditions), independent of each other (no endemic communicable diseases) and known or estimable (insurers are able to estimate future claims and adjust premiums for risk); and there are no major problems with adverse selection, risk selection, moral hazard and monopoly (Reference BarrBarr, 2004).

Table 1.2 Overview of spending on health in the countries in this volume, 2017

| Countries | Public spending on health as a share of GDP (%) | Public spending on health as a share of current spending on health (%) | Other compulsory spending on health as a share of current spending on health (%) | Voluntary PHI as a share of current spending on health (%) | Out-of-pocket payments as a share of current spending on health (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-income countries | |||||

| Australia | 6.3 | 69 | 0 | 10 | 18 |

| Canada | 7.8 | 74 | 0 | 10 | 14 |

| Chile | 4.5 | 50 | 10 | 6 | 34 |

| France | 8.7 | 77 | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Germany | 8.7 | 78 | 7 | 1 | 13 |

| Ireland | 5.3 | 73 | 0 | 13 | 12 |

| Israel | 4.7 | 64 | 0 | 11 | 22 |

| Japan | 9.2 | 84 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| Netherlands | 6.5 | 64 | 17 | 6 | 11 |

| Republic of Korea | 4.4 | 57 | 1 | 7 | 34 |

| Switzerland | 3.8 | 30 | 33 | 7 | 29 |

| United States of America | 8.6 | 50 | 34 | 0 | 11 |

| Upper middle-income countries | |||||

| Brazil | 4.0 | 42 | 0 | 29 | 27 |

| South Africa | 4.4 | 54 | 0 | 36 | 8 |

| Lower middle-income countries | |||||

| Egypt | 1.8 | 33 | 0 | 1 | 60 |

| India | 1.0 | 27 | 0 | 5 | 62 |

| Kenya | 2.4 | 49 | 0 | 10 | 24 |

Notes: GDP: gross domestic product. ‘Public spending on health’ comprises government budget allocations and social insurance contributions. In Chile, this includes income-based contributions for substitutive PHI. ‘Other compulsory spending on health’ comprises the following non-income-based contributions: for substitutive PHI above the income-based contribution (Chile); for complementary PHI covering co-payments among employees, which has been compulsory for employees since 2016 (France); for substitutive PHI, which has been compulsory for people who opt out of national health insurance since 2009 (Germany); for national health insurance above the income-based contributions (the Netherlands); for national health insurance (Switzerland); for compulsory and voluntary cover offered by private insurers (United States of America). In Taiwan, China, PHI accounts for 9.5% and out-of-pocket payments for 34.7% of current spending on health (Kwon, Ikegami & Lee, this volume). If tax subsidies for voluntary PHI are included, then the share of current spending on health channelled through voluntary PHI rises from 36% to 47% in South Africa and from 10% to 13% in Australia and Canada.

Moral hazard and monopoly issues can be problematic for both compulsory and voluntary health insurance and researchers have questioned whether moral hazard poses a genuine threat to efficiency in health insurance (Reference NymanNyman, 2004; Reference Einav and FinkelsteinEinav & Finkelstein, 2018). This leaves probabilities, adverse selection and risk selection as the most likely sources of failure in markets for voluntary health insurance.

Insurance premiums are a function of the probability of illness and the expected costs of treating ill health. They are considered to be actuarially fair when they reflect the health risk of the pool of people being covered, allowing the insurer to meet its obligations to members of the pool and avoid financial losses for the firm.

Actuarial fairness is challenging to achieve for several reasons. First, it is difficult to sustain a voluntary health insurance market among people who are already ill or at high risk of becoming ill and in the context of epidemics (Reference BarrBarr, 2004). Second, if people conceal information and buy insurance for a premium that does not accurately reflect their health risk, the financial viability of the pool will be jeopardized: premiums will rise over time and those with a lower risk of ill health will leave to buy cheaper insurance from other firms (Reference AkerlofAkerlof, 1970). So-called adverse selection can lead to the collapse of a market. Ensuring stability is the main reason why private health insurance markets require financial regulation in the form of standards for insurer entry, operation, exit and reporting, although adverse selection is most effectively addressed by making health insurance compulsory. Third, to prevent adverse selection, insurers will engage in risk selection, attempting to attract low-risk people to the pool and deter high-risk people from enrolling.

Owing to risk selection, some people may not be able to obtain insurance if insurers reject applications for coverage; some may not be able to obtain sufficient insurance if pre-existing conditions or certain types of treatment are excluded from coverage; and some may not be able to obtain insurance at a price they can afford to pay. Private health insurance will therefore segment risk among enrollees as well as between those with and without private health insurance. This in turn limits redistribution between rich, poor, healthy and sick; violates the equity principle of access to health care based on need rather than ability to pay (Reference CulyerCulyer, 1989); and exacerbates inequality in the health system. Some of these consequences can be avoided through material regulation involving rules around premiums, benefits and other contractual conditions (Reference HsiaoHsiao, 1995).

Risk selection has other unwanted side-effects. It is a pure cost from a health system perspective, because it fails to produce any social benefit, and it may lower incentives for efficiency in the organization and delivery of health insurance and health services if insurers maintain margins by selecting low-risk people rather than by streamlining operations and exerting leverage over providers (Reference EvansEvans, 1984; Reference RiceRice, 2001; Reference RiceRice, 2003).

While risk segmentation is primarily the outcome of market failures, it is sometimes compounded by public policy regarding the boundary between publicly and privately financed coverage and the nature and extent of regulation.

How we got to where we are now: the importance of history and politics

Economic theory clearly indicates some of the likely outcomes of fostering private health insurance. To understand how private health ins- urance affects health system performance also requires context-specific analysis. The diversity that makes private health insurance difficult to define means its impact will vary depending, to a large extent, on public policy. Two markets that play the same role can have divergent outcomes because of differences in public policy, which in turn may reflect the way in which public policy has been shaped by history (past events) and politics (stakeholder interests).

Each case study in this volume reviews the origins of private health insurance and developments over time. Taken together, the case studies reveal a number of patterns in how markets were established, their evolution and the role that private health insurance has played in national debates about moving towards universal health coverage.

As the precursor to publicly financed coverage, private schemes were usually organized around employment

Private health insurance generally predates national health insurance. In its earliest forms, before the rise of modern medicine, its primary purpose was to compensate people for earnings lost through illness. For this reason it was exclusively linked to employment. Over time, loss-of-income schemes, first established by guilds of skilled workers in Europe in the Middle Ages, gave way to occupation-based mutual aid associations serving industrial workers, laying the foundation for contemporary welfare states (Reference Abel-SmithAbel-Smith, 1988).

By the mid-19th century, employment-based private health insurance offered by mutual associations had become the norm across much of Europe (Reference Saltman, Busse and FiguerasSaltman, Busse & Figueras, 2004). In South Africa, private schemes were introduced at the turn of the 20th century, under British rule, for white mine workers; they remained the preserve of white South Africans until the 1970s (McIntyre & McLeod, this volume). The non-profit health plans operating in Israel today emerged from the trade union movement of the early 1900s and came under government regulation following the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 (Brammli-Greenberg & Waitzberg, this volume).

As medical care progressed and treatment became more costly, health care providers began to develop health insurance themselves, to enable patients to pay for their services. From the beginning of the 20th century, physicians in the Netherlands and hospitals and physicians in Australia, Canada and the United States were active in setting up schemes, some of which are still in operation. Provider-initiated schemes were usually linked to hospitals run by the voluntary (charitable) sector. Consequently, many were non-profit-making entities operating according to social principles such as open enrolment (accepting all applicants) and community rating (basing premiums on average risk rather than individual risk).

In a third stage of development, schemes organized around employment or initiated by health care providers were joined by insurers operating on a commercial basis.

The middle-income countries in this volume have tended to follow a different path. In Chile, Brazil, Kenya and India, private health insurance emerged following government decisions to enhance private involvement in the health system after some form of national health insurance had already been established. These decisions took place in 1976 in Brazil, 1980 in Chile, the 1980s and 1990s in Kenya and 1999 in India. Something similar occurred in central and eastern Europe in the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when new laws allowed private health insurance to operate alongside publicly financed coverage (Reference 39Kornai and EgglestonKornai & Eggleston, 2001; Reference Thomson and KutzinThomson, 2010).

In Japan, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, China, private health insurance has its origins in accident or life insurance and continues to be linked to life insurance and other types of financial investment vehicle, often offering cash benefits in case of illness.

Compulsory publicly financed coverage was a response to the failure of voluntary schemes to cover the whole population

Very few of these early forms of private health insurance succeeded in covering more than a minority of the population, partly due to their roots in employment and their voluntary nature, but also because they were unaffordable for many people, including those most in need of protection from health care costs.

In some countries, access to employment-based health insurance was enhanced through schemes organized by charitable entities (most often linked to the Church) and local authorities, but even these were not enough to achieve universal population coverage. A census of the Swiss population held in 1903 found that only 14% belonged to any type of scheme, including those run by the Catholic Church, cantons and municipalities (Crivelli, this volume).

Following the example set by Germany in 1883 (Ettelt & Roman-Urrestarazu, this volume), governments began to think about setting up some form of national system that would extend coverage to more people. Private schemes were uniquely placed to play a major role in these new arrangements. Non-profit actors adhering to social principles formed the basis for what would eventually become national health insurance in Germany, the Netherlands and Israel, leaving other private actors to cover any remaining gaps. France proved to be the exception: when publicly financed coverage was established in 1945, the government chose to introduce new institutions rather than build on the tradition established by mutual associations known as mutuelles, even though the mutuelles covered around two thirds of the population by 1939.

It was at the point of instituting national health insurance that the key distinction between schemes shifted from type of actor to compulsory versus voluntary.

Private interests consistently tried to block the expansion of publicly financed coverage

In many countries a variety of stakeholders (health care providers, private insurers, people with private health insurance and political parties) have taken steps to prevent the development of national health insurance, most often by arguing that it should be limited to poorer people.

For example, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans created by health care providers in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s were part of a deliberate and ultimately successful attempt by the medical profession to construct an alternative to publicly financed coverage (Brown & Glied, this volume). To this day, the publicly financed schemes that were eventually implemented in 1965 are limited to covering older people (Medicare) and poor people (Medicaid), together accounting for only one third of the population.

In Germany, proposals to extend publicly financed health coverage to the whole population, which would effectively abolish substitutive private health insurance, have always been opposed not just by private insurers and health care providers (who benefit from charging higher fees when treating privately insured people), but also by the relatively rich households who rely on private coverage and fear having to accept a lower standard of access to health care under a universal scheme (Ettelt & Roman-Urrestarazu, this volume).

With the exception of Germany and the United States, private insurers have generally failed to prevent the implementation of a fully universal scheme. Nevertheless, in several instances they have delayed it and, by being part of the health system landscape, they have been able to influence the parameters for reform.

In Switzerland, the government’s first choice for national health insurance was to establish a system run by public entities, but opponents launched a referendum against it, and it was rejected by popular ballot in 1900 (Crivelli, this volume). Burnt by this experience, the government’s next attempt aimed to overcome opposition by leaving the management of the new system in the hands of private actors and allowing cantons to decide whether health insurance should be mandatory. Although the revised proposal was accepted by referendum in 1912, it paralysed reform efforts for over 80 years; health insurance only became compulsory for the whole population in 1996.

In the Netherlands, the national medical association not only ensured that the earliest attempts to introduce national health insurance, from 1901 onwards, were restricted to poor people so as not to damage physician incomes; they also encouraged physicians to set up their own health insurance schemes, which soon came to dominate the market (Maarse & Jeurissen, this volume). Lobbying by private insurers subsequently stood in the way of efforts to extend publicly financed coverage to the whole population throughout the 20th century (Maarse & Jeurissen, this volume). As in Germany, insurer resistance to change was bolstered by resistance on the part of those covered by substitutive private health insurance. It is therefore not surprising that when a universal scheme was finally set up in 2006, it compensated private insurers by allowing them to take part in the national scheme, alongside sickness funds, and limited the extent of direct cross subsidies from richer to poorer households.

Australia’s first attempt at creating a national scheme (known as Medibank) was achieved in 1974 under a Labour government after years of opposition from a coalition of private insurers, private hospitals, physicians practising privately and the politically conservative Liberal Party (Hall, Fiebig & van Gool, this volume). The scheme did not last long. In 1976, a newly elected conservative coalition turned it into a government-owned insurance company, renaming it Medibank Private, and forced it to compete with private insurers. A genuinely national scheme was not re-introduced until the Labour Party returned to government in 1984. Since then, private schemes have mainly played a supplementary role.

Government intervention in private health insurance markets has intensified

Looking at the development of private health insurance markets indicates minimal change in role. The only significant change has been the abolition of substitutive private health insurance in the Netherlands in 2006. By far the most striking and widespread phenomenon has been the intensification of government intervention over time. Box 1.2 highlights major developments in private health insurance markets across the 18 countries, starting in the second half of the 20th century, after some form of national health insurance had been established in most countries, and going up to the end of 2017.

Some of the need for greater intervention can be linked to changes in market structure leading to changes in market conduct. Initially, markets were often dominated or exclusively run by non-profit organizations offering people relatively easy access to private coverage based on social principles such as open enrolment and community rating. The entry of commercial insurers operating on different principles (risk rating, exclusion of pre-existing conditions, rejection of applications) threatened this business model in many countries, among them Australia, Canada, France, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States. In response, some non-profit entities adopted a more commercial approach, meaning that governments could no longer rely on the presence of mutual associations to ensure access to private health insurance.

Box 1.2 Major developments in markets for private health insurance in this volume, 1960–2017

1960s

The Netherlands reaffirms compulsory publicly financed coverage for lower-earning workers only, allowing higher earners to choose between public, private or no coverage (1964).

1970s

Germany makes public coverage compulsory for white-collar workers with earnings below a specified threshold and allows higher-earning white-collar workers to choose public, private or no coverage (1970).

Private insurers are allowed to operate in Brazil (1976).

1980s

Chile introduces choice of public or private coverage for the whole population (1981).

Australia introduces tax rebates for private health insurance (1981) and later removes them (1983).

The Netherlands abolishes choice of public or private coverage; those with earnings over a threshold are no longer eligible for publicly financed coverage; regulation of the substitutive private health insurance market intensifies (1986).

Germany extends choice of public, private or no coverage to all higher-earning employees (1989).

Publicly financed health plans in Israel institute compulsory supplemental coverage (mid-1980s); this is later prohibited (1995) but the health plans can offer it on a voluntary basis as separate financial entities.

Deregulation of the private health insurance market in South Africa (1980s, early 1990s).

1990s

The Third Non-Life Insurance Directive establishes a single European market in health insurance (1992).

Medical savings accounts established in the private health insurance market in South Africa (1994).

Liberalization of the private health insurance market in Ireland, as required by EU law; the government introduces material regulation of private health insurance, including a risk equalization scheme (1994).

Germany makes the decision to opt for private rather than public coverage irreversible for those aged 65 years and above; introduction of a standard tariff (premium) in substitutive private health insurance (1994).

National health insurance offered by competing health plans becomes mandatory in Israel (1995).

Australia introduces tax penalties for high earners who do not purchase private health insurance (1997).

South Africa introduces material regulation of the private health insurance market (1998, with effect from 2000).

Tighter material regulation of supplemental plans introduced in Israel (1998).

Australia re-introduces tax rebates for private health insurance (1999).

Legislation liberalizes the insurance sector in India, including health insurance (1999).

2000s

Creation of Superintendencia de ISAPREs as the regulator of private health insurance in Chile (2000).

Germany makes the decision to opt for private coverage irreversible for people aged 55 years and over (2000).

France provides free complementary private health insurance covering co-payments to poor households (CMU-C, 2000) and subsidizes private health insurance for poor households not eligible for CMU-C (ACS, 2002).

Introduction of lifetime community rating in private health insurance in Australia (2000).

All private health insurers in Brazil are mandated to offer a reference plan as an option (2000).

Health savings accounts established in the private health insurance market in the United States (2002).

Health plans in Israel to compensate national health insurance retroactively for the use of infrastructure and staff within supplemental insurance (2002).

Chile introduces minimum benefits for private health insurance (2003).

The Fillon Law in France introduces tax exemptions for employers offering mandatory group private health insurance contracts that comply with certain rules (contrats solidaires) (2003) (further strengthened in 2010 and 2013); private health insurance contracts must meet additional criteria (contrats responsables) to enable insurers to qualify for exemption from premium income tax (2004).

Introduction of the Universal Health Insurance scheme in India (2004).

The Netherlands establishes a universal scheme, abolishing substitutive private health insurance (2004, with effect from 2006).

A court ruling against current restrictions on private health insurance in the province of Quebec in Canada (2005).

Israel introduces regulation to separate supplemental insurance from national health insurance (2005).

Proposed expansion of the private health insurance market in the Republic of Korea (2005).

Ireland triggers the risk equalization scheme (2005) and is challenged by BUPA in the High Court (2006).

Kenya strengthens the regulatory framework for private health insurance (2006).

Removal of tariffs from general insurance in India, including for private health insurance (2007).

South Africa commits to pursuing a national health insurance system (2007).

New commercial policies for private surgery in Israel are prohibited from covering expenses that are covered by supplemental insurance (2007).

Health insurance becomes universally compulsory in Germany; substitutive private health insurance is subject to extensive new regulations (2009).

2010s

Introduction of means testing for the private health insurance tax rebate in Australia (2010).

Tax on responsible contracts re-introduced in France but at lower rates than non-responsible contracts (2010).

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) enacted in the United States (2011, with effect from 2014).

Green Paper on national health insurance in South Africa suggests private health insurance could be restricted to so-called top-up insurance (2011; reiterated in a White Paper in 2015).

Risk equalization scheme implemented in Ireland (2012); private bed charges to be levied on the use of any bed in public hospitals by privately insured patients (2014); lifetime community rating introduced (2015).

Switzerland introduces choice of hospital for all (previously only available through voluntary private health insurance) (2012).

Commercial insurers in Israel are prohibited from reimbursing surgeries covered by national health insurance or supplemental private health insurance (2014).

France extends ACS eligibility (2015).

Employers in France are mandated to provide employees with complementary private health insurance (2016).

Greater intervention has also followed market expansion or growth, which makes problems with private health insurance more visible and less acceptable. In such instances, intervention has been driven by three aims:

enhancing consumer protection, occasionally in response to insurer fraud (Kenya) or malpractice (Germany), but more commonly to reduce financial and transaction costs for consumers in the face of multiple and potentially confusing coverage options (almost all of the countries in this volume);

protecting publicly financed coverage from fiscal pressures exacerbated by (mainly) substitutive and supplementary private health insurance; this type of intervention has usually tried to limit the damage associated with allowing people to choose between public and private coverage by restricting (Germany) or abolishing (the Netherlands) access to publicly financed coverage for some people; clarifying and enforcing boundaries between public and private coverage (Ireland, Israel); and reducing tax subsidies for private health insurance; and, overwhelmingly,

maintaining or enhancing access to private health insurance and financial protection for those with private health insurance; Table 1.3 provides examples of the types of material regulation introduced in the countries in this volume.

Table 1.3 Examples of measures to ensure voluntary private health insurance is accessible, affordable and offers quality coverage

| Measures | Countries |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | |

| Open enrolment | Australia, Germany, Ireland, Israel, South Africa |

| Lifetime cover | Brazil, Germany, Ireland |

| Guaranteeing supply of marketed policies | Australia, Brazil |

| Prohibiting switching penalties | Netherlands, Switzerland |

| Rating of plans to facilitate choice | Australia |

| Other | Francea, Kenyab |

| Affordability | |

| Community-rated premiums | Australia, Brazil, Chile, Ireland, Israel, South Africa |

| Risk equalization to support community rating | Chile, Ireland |

| Ageing reserves | Germany |

| Premium caps | Brazil, Germany |

| Premiums subsidized, discounted, waived or fully covered by the government | Australia, France, Germany, Ireland, South Africa |

| Limits on insurer profits | Australia, Chile |

| Scope and depth of coverage | |

| Cover of pre-existing conditions | Brazil, Germany, Ireland, Israel |

| Minimum or standard benefits | Brazil, Chile, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, South Africa |

| Caps on user charges in private health insurance | Chile, Germany, South Africa |

| Prohibition of benefit ceilings | France, Chile, South Africa |

| Provisions to encourage cover of gaps in publicly financed coverage | Australia |

Notes:

a Making it mandatory for employers to buy complementary private health insurance for employees (from 2016).

b Allowing monthly rather than annual payment of premiums.

The need to secure affordable access to private health insurance is arguably greatest where private health insurance plays a substitutive role or a complementary role covering co-payments. It is no coincidence, therefore, that these are the private health insurance markets in which governments have intervened most heavily and persistently (Chile, France and Germany, and the Netherlands before the introduction of a universal scheme in 2006). Intervention has intensified in the supplementary markets in this volume too, to meet all three of the aims highlighted above (Australia, Brazil, Ireland, Israel, Kenya and South Africa).

Private health insurance today: implications for health system performance

The case studies in this volume provide empirical evidence on the impact of private health insurance on health system performance in three areas (financial protection, access to health services, and efficiency and quality in health service organization and delivery) as well as on the contribution of private health insurance to relieving fiscal and other pressures on health systems. The focus of this section is on voluntary private health insurance rather than compulsory coverage operated by private insurers as in the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United States.

Does private health insurance enhance financial protection by filling gaps in publicly financed coverage?

Private health insurance will enhance financial protection for those who buy it by reducing their exposure to out-of-pocket payments. How well it is able to fill gaps in publicly financed coverage at health system level can be assessed by looking at data on private health insurance as a share of total and private spending on health and information on the share of the eligible population covered by private health insurance.

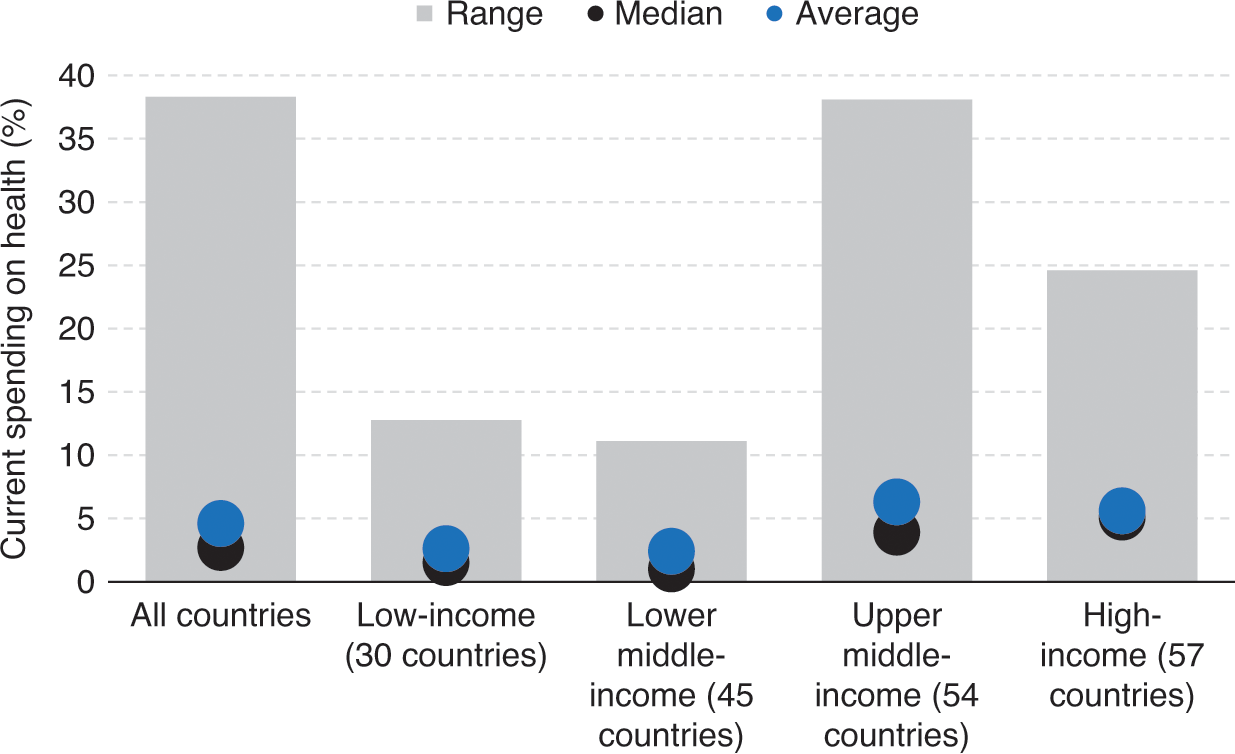

Global spending data show that the contribution of private health insurance to current spending on health is marginal in the vast majority of countries. Across all countries, voluntary private health insurance accounts for only 4.6% on average, ranging from 2.4% in lower middle-income countries to 6.3% in upper middle-income countries (Fig. 1.1). The range in Fig. 1.1 shows there is a great deal of variation at country level, particularly in upper middle-income countries.

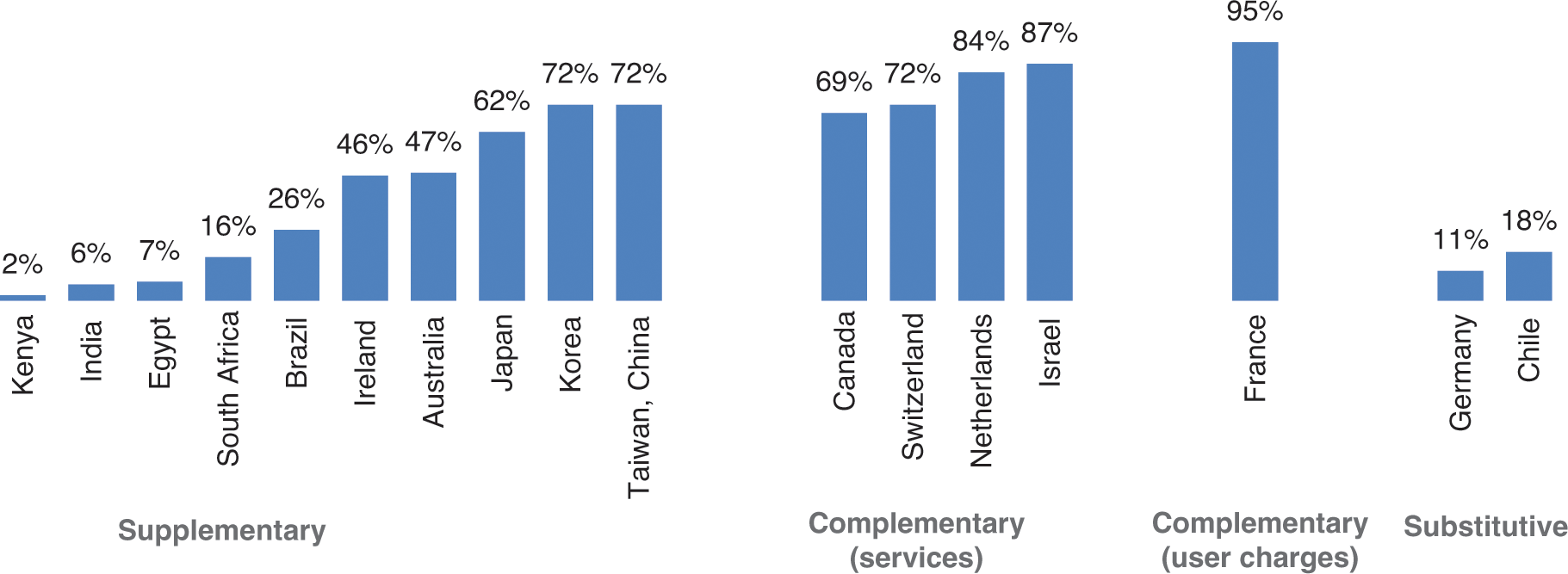

Figure 1.4 Share (%) of the population covered by private health insurance in the countries in this volume by role, latest year available

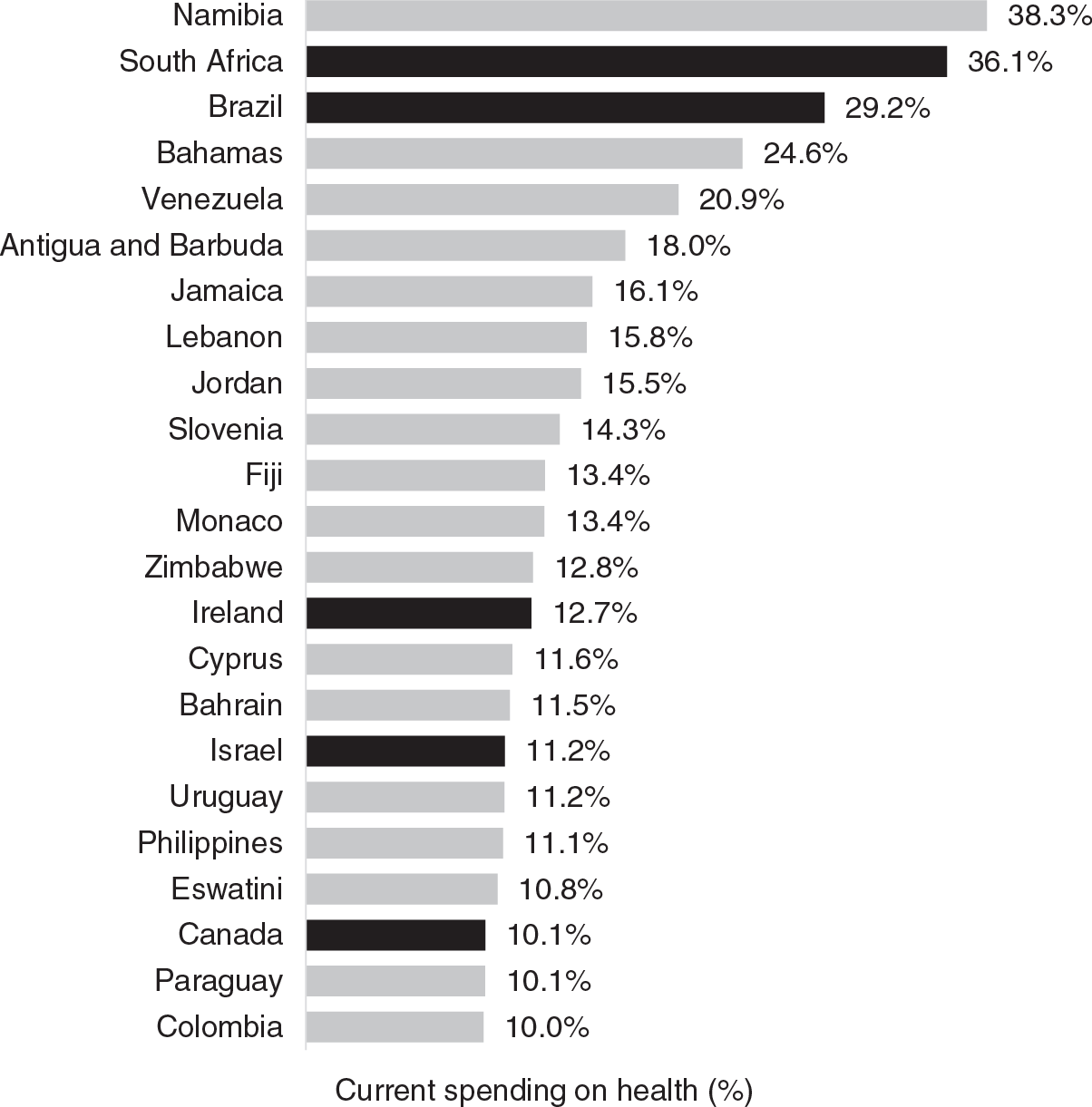

Voluntary private health insurance accounts for more than 10% of current spending on health in only 23 countries (Fig. 1.2). Over half of these are middle-income countries, many in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. In over 80 countries, voluntary private health insurance accounts for less than 2% of current spending on health. Over time, the voluntary private health insurance share of current spending on health has remained relatively stable.

Figure 1.2 Countries globally in which voluntary and compulsory private health insurance accounts for at least 10% of current spending on health, 2017

Figure 1.1 Voluntary private health insurance as a share (%) of current spending on health globally by country income group, 2017

Notes: Countries covered in this volume are marked in black. Voluntary private health insurance accounts for less than 10% of current spending on health in Australia, Chile, Egypt, Germany, India, Kenya, Japan, the Netherlands, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, China, Switzerland and the United States of America.

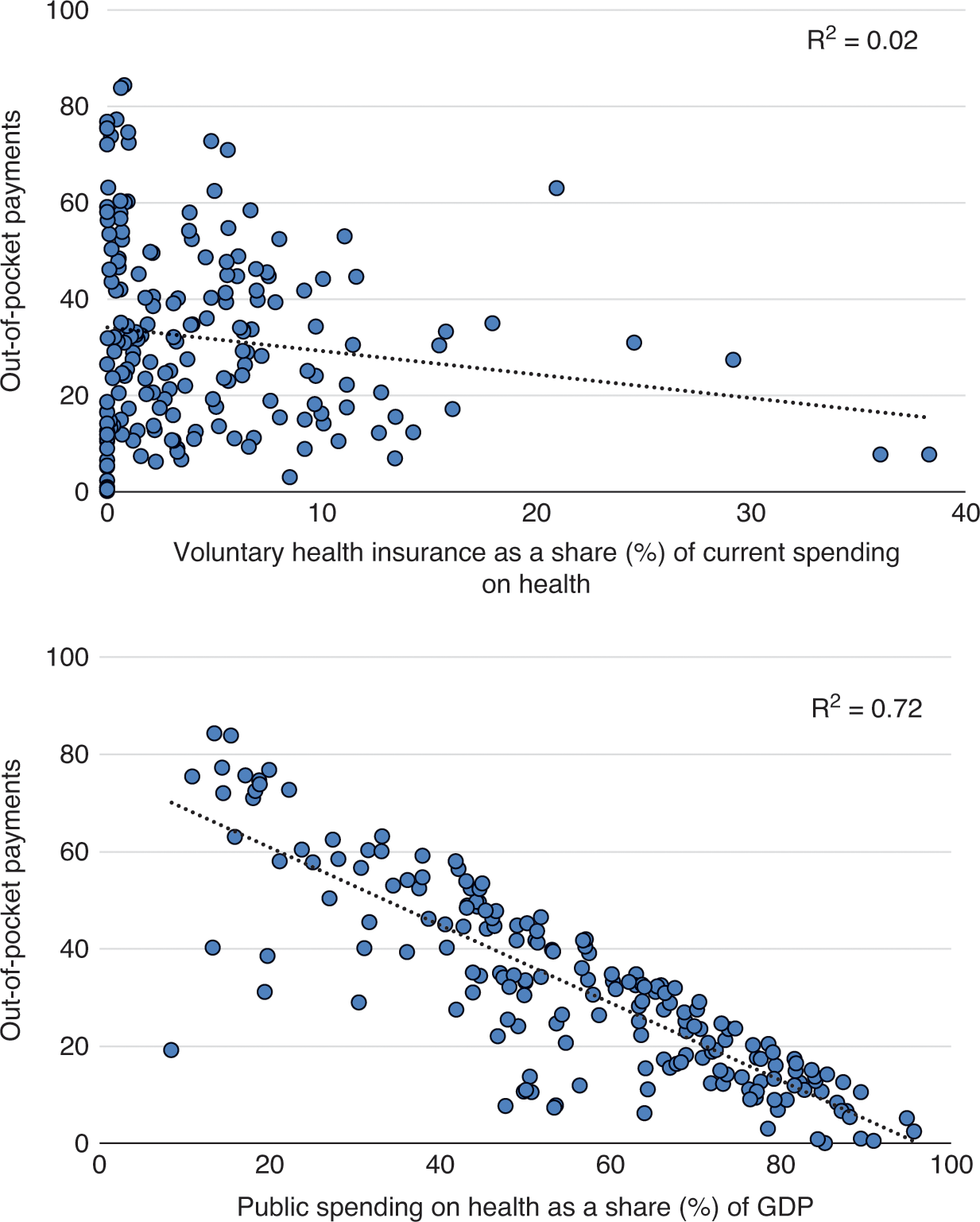

Globally, the relationship between voluntary private health insurance and the out-of-pocket payment share of current spending on health is very weak (Fig. 1.3, first panel). In spite of significant gaps in coverage in many countries, as demonstrated by high levels of out-of-pocket payments, spending on voluntary private health insurance is low. This indicates that while gaps in publicly financed coverage are a prerequisite for voluntary private health insurance, they are not enough for a private health insurance market to develop and grow. In 2017, out-of-pocket payments were the dominant source of private spending on health in over 95% of countries (WHO, 2020). The voluntary private health insurance share of current spending on health exceeded the out-of-pocket payment share in only 9 out of 186 countries: Namibia, South Africa, Brazil, Slovenia, Monaco, Ireland, Eswatini, Qatar and Botswana. Even among the generally large markets selected for this volume, voluntary private health insurance accounts for over 30% of private spending on health in only eight countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands and South Africa.

Figure 1.3 Relationship between out-of-pocket payments as a share of current spending on health and voluntary private health insurance and public spending on health globally, 2017

Across countries, there is a much stronger association between public spending on health and out-of-pocket payments (Fig. 1.3, second panel), which suggests that increases in public spending on health are much more likely to reduce gaps in coverage than increases in spending through voluntary private health insurance.

Data on voluntary private health insurance spending need to be interpreted alongside information on the role that private health insurance plays and the share of the population covered by private health insurance. In South Africa, for example, private health insurance playing a supplementary role covers around 16% of the population (Fig. 1.4), overwhelmingly people from higher income groups (McIntyre & McLeod, this volume), but voluntary private health insurance premiums account for over a third (36%) of current spending on health (Table 1.2). In contrast, supplementary private health insurance in Ireland accounts for a much smaller share of current spending on health (around 13%) but covers close to half of the population (46%). Similarly, private health insurance playing a complementary role in countries like France, Israel and the Netherlands accounts for a much smaller share of current spending on health than in South Africa, but covers over 80% of the population (Fig. 1.4). If tax subsidies are included in private health insurance spending, the share of current spending on health channelled through private health insurance in South Africa rises to 47% (WHO, 2020).

Notes: The figure includes 186 countries. GDP: gross domestic product.

Supplementary private health insurance does not usually achieve high levels of population coverage, as Fig. 1.4 shows. Relatively high demand in Australia and Ireland is fuelled by long waiting times for publicly financed specialist care, substantial tax incentives to buy private health insurance (although these have been reduced over time) and penalties for those who do not buy private health insurance at younger ages (Turner & Smith and Hall, Fiebig & van Gool, this volume). The very high levels of population coverage in Japan, Korea and Taiwan, China are not typical and largely reflect the sale of private health insurance alongside life insurance (Kwon, Ikegami & Lee, this volume).

Rates of population coverage appear to be high where private health insurance plays an explicitly complementary role (Fig. 1.4). Canada, Israel and the Netherlands are, however, outliers in terms of complementary private health insurance covering services; in other countries, this type of market rarely covers more than one third of the population and often much less than that (Reference Sagan and ThomsonSagan & Thomson, 2016a).

In markets for complementary private health insurance covering user charges, globally only Croatia and Slovenia come close to France in terms of population coverage (Reference Sagan and ThomsonSagan & Thomson, 2016a; Reference Vončina and RubilVončina & Rubil, 2018; Reference RegionalWHO Regional Office for Europe, 2019).

Various mechanisms help to explain high levels of take up in these markets for complementary private health insurance:

private health insurance being sold by the same entities that provide publicly financed coverage in Croatia, Israel and the Netherlands; this was also the case in Slovenia when the market was first established and high rates of population coverage were achieved;

easy access to the private health insurance market ensured through open enrolment in Croatia, France, Israel, the Netherlands and Slovenia;

affordable access to private health insurance ensured through regulation in Croatia, Israel and Slovenia and targeted tax subsidies that make private health insurance free for the poorest households in Croatia and France; and

linking private health insurance to employment so that it is compulsory for employees (France) or de facto near universal for employees (Canada).

Substitutive private health insurance is the only form of coverage available to some of the population in Germany (people aged over 55 years since 2000, people aged over 65 years since 1994) and the United States (non-poor people under 65 years), as well as in the Netherlands between 1986 and 2005 (richer households). Private health insurance has not been able to fully fill the gap in publicly financed coverage in the United States, even after the passing of the Affordable Care Act in 2014. In Germany and the Netherlands, however, gaps have been filled through extensive and increasing regulation of the private health insurance market involving open enrolment, lifetime cover, minimum benefits, premium controls and, eventually, compulsion.

Just because people have private health insurance does not mean that they do not experience gaps in coverage. In France, for example, the quality of private health insurance coverage (the extent to which it covers all the user charges a person has to pay) varies by socioeconomic status, with better-off people enjoying a greater degree of financial protection (Couffinhal & Franc, this volume). Erosion in the quality of private health insurance coverage over time has been one of the notable features of some markets. It is particularly evident in markets where medical savings accounts have been introduced (South Africa and the United States), but is also documented in France, Germany (through the growing use of deductibles for substitutive private health insurance policies) and Australia.

Does private health insurance enhance access to health services?

Across the countries in this volume, and beyond, voluntary private health insurance is systematically more likely to be bought by people who are relatively wealthy, employed, better educated and living in urban areas with access to private health care providers (Reference Sagan and ThomsonSagan & Thomson, 2016a). The lowest levels of take up are often among people in vulnerable situations: people living in poverty, older people and people who are ill or at high risk of ill health.

This pattern has three negative consequences for health system performance. First, it exacerbates socioeconomic inequality in access to health care in a wide range of countries: in Brazil, for example, fewer than 6% of people in the poorest income quintile had private health insurance in 2013, compared with around 65% of people in the richest (Diaz et al., this volume). Second, it skews the distribution of health care away from need, leading to concerns for efficiency in addition to concerns for equity. And third, it segments risk in the health system, as described in Box 1.3. The examples in Box 1.3 show that risk segmentation can arise by design as well as due to risk selection on the part of private insurers.

Box 1.3 Selected examples of risk segmentation linked to private health insurance

National health insurance in Germany was initially only compulsory for blue-collar workers, on the grounds that richer workers did not require protection organized by the state. Later, richer people were permitted to opt into the national scheme. If they chose not to, they could obtain voluntary coverage from private insurers. By design, the option of substitutive private coverage is limited to higher earners, segmenting the population by income. The privately insured are also generally healthier than those in the national scheme thanks to risk selection by private insurers, who are allowed to rate premiums on the basis of individual health risk and can offer subscribers lower premiums in return for higher co-payments in the form of deductibles. This exacerbates population risk segmentation and segments risk among those with private health insurance. Over time, people with private coverage aged, their health deteriorated and their premiums rose, in part owing to miscalculation of lifetime risk by private insurers. Some of them tried to return to the national scheme, adding to financial pressure in the publicly financed part of the health system. The federal government intervened heavily in the private health insurance market in 1994, prohibiting anyone who had opted for private coverage from returning to the national scheme if they were aged over 65 years. In 2000, it lowered the age restriction to 55 years and introduced measures to secure access and financial protection for people now forced to rely on private coverage, including a limit to deductible amounts (Reference Thomson and MossialosThomson & Mossialos, 2006).

In France, private health insurance plays a complementary role, covering user charges for publicly financed health services. Private health insurance coverage rose steadily after 1945, reaching 86% of the population in 2000. In response to evidence of socioeconomic inequality in access to health care linked to private health insurance, the Government introduced vouchers (CMU-C) for people on low income to purchase private health insurance in 2000 and subsidies (ACS) for those just above the threshold for vouchers in 2005. As a result of these measures, private health insurance coverage exceeded 90% of the population by 2015. Unequal access to private health insurance remains a challenge, however, with financial barriers being the most common reason that people give for not being covered. As in Germany, the population is segmented twice: first, because private health insurance is more affordable for richer people; and second, through subsidies to purchase private health insurance, which only benefit the poorest people. The 2016 requirement for all employers to offer private health insurance to their employees is likely to add another layer of segmentation. It aims to improve access to group contracts, known to be more advantageous than individual contracts. Although this may reduce unequal access to private health insurance among employees, it may increase inequality between salaried employees and other groups of people (students, retirees and unemployed or self-employed people.

The development of supplementary private health insurance in South Africa has led to segmentation by race and income. Before the 1970s, private health insurance only covered white workers. Later, take up encompassed other people, encouraged by tax subsidies for government employees. Today, private health insurance offers access to private health care providers to a relatively wealthy minority (16% of the population), while the majority (84%) rely on publicly financed services in public facilities. The magnitude of spending through private health insurance (about 47% of total spending on health) significantly limits the potential for income and risk cross-subsidies in the health system. Medical savings accounts introduced in 1994 and held by about 45% of those with private health insurance segment risk within the market.

Does private health insurance enhance efficiency and quality in health service organization and delivery?

The premise underlying this question is that private entities are more likely than public bodies to improve some aspects of health system performance because of incentives created by the pursuit of profit (or margins) in a competitive environment (Reference Gilbert and TangGilbert & Tang, 1995; Reference JohnsonJohnson, 1995; Reference Chollet and LewisChollet & Lewis, 1997). In health insurance markets this would be achieved through strategic purchasing leading to greater efficiency and quality in health service delivery and through efforts to minimize administrative costs.

In practice, however, striving for efficiency gains through strategic purchasing has not been the driving force behind private health insurance markets. Historically, it was common for health insurance markets to operate on a retrospective reimbursement basis, simply offering people compensation for health care costs that they had already incurred. Markets for private health insurance often kept this model, even after purchasers operating under national health insurance had switched to the provision of in-kind benefits, either because of their need to provide customers with enhanced choice of provider in substitutive and supplementary markets or because their role was to cover the costs not covered by national health insurance in complementary markets.

As a result, outside the United States, insurers in most private health insurance markets have not engaged in strategic purchasing. Very few have been able to exercise leverage over health care providers through selective contracting, prospective payment, performance monitoring or vertical integration. Instead, many have maintained margins by selecting risks, especially when competing with national health insurance (as in Chile, Germany and the Netherlands before 1986), and by shifting costs onto households through the use of co-payments, benefit ceilings, deductibles and medical savings accounts.

The failure of private insurers to carry out strategic purchasing can push up prices throughout the health system, undermining overall performance. In South Africa, for example, private insurers have had limited purchasing power over health care providers and the introduction of medical savings accounts in the 1990s further weakened their leverage (McLeod & McIntyre, this volume). As a result, private hospital prices in South Africa are similar to prices in countries with much higher levels of GDP, such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom, making it more expensive for the public sector to recruit and retain medical specialists (Reference Lorenzoni and RoubalLorenzoni & Roubal, 2016).

Where data are available, they suggest that administrative costs are almost always higher in private health insurance markets than under publicly financed coverage (OECD, 2018; Reference Sagan and ThomsonSagan & Thomson, 2016a). Higher administrative costs in private health insurance markets may be attributed to the bureaucracy required to assess risk, rate premiums, design products and review claims, as well as the duplication of tasks necessitated by fragmented pooling.

Does private health insurance relieve fiscal and other pressures on health systems?

Private health insurance may relieve fiscal pressure if it covers a significant share of the population. It is difficult to think of private health insurance as providing genuine fiscal relief when it draws financial and other resources away from those who need them most, however: in other words, when the relief for the government of not having to pay for the things private health insurance covers is offset by a reduction in the performance of the publicly financed part of the health system.

The experience of the countries in this volume highlights different ways in which private health insurance affects the magnitude and allocation of public resources and can therefore add to fiscal pressure. These effects are often most evident in substitutive private health insurance markets and large supplementary private health insurance markets promoting faster access to health care and enhanced choice of health care provider.

Loss of financial contributions to public coverage:

In Chile and Germany (and in the Netherlands before 2006), publicly financed coverage loses higher than average income-related contributions when people opt for private health insurance, in Germany because only richer people are given this choice and in Chile because those opting out are more likely to come from richer groups. This leaves the publicly financed scheme with a lower level of funding per person than it would have if it covered the whole population. The loss of contributions from richer people is compounded by the fact that public funds cover a pool with a higher than average risk of ill health than the private health insurance pool (Box 1.3; Ettelt & Roman-Urrestarazu, this volume; Maarse & Jeurissen, this volume). In the Netherlands, this led the government to introduce a levy on those with private health insurance, to compensate the publicly financed scheme for the additional cost of covering older people.

Porous borders between public and private coverage:

In Germany, private health insurance premiums rose rapidly with age in the 1980s and early 1990s (in part due to miscalculation on the part of private insurers), causing some older and sicker people to take early retirement so that they could return to public coverage. The influx of older people added to the fiscal pressure faced by the publicly financed scheme and led the government to prohibit people aged over 55 years from returning to public coverage once they had made the decision to opt for private health insurance. In turn, the government was then compelled to introduce a wide range of regulations to ensure that private health insurance would remain accessible and affordable for these older people.

The Netherlands faced a similar situation in the 1970s and early 1980s, which was why choice of public or private coverage was abolished in 1986 in favour of excluding richer people from public coverage. As in Germany, this move required the government to intervene heavily in the market to ensure access and affordability for those reliant on private health insurance.

Porous borders between public and private coverage are also an issue in Chile.

Inadequate compensation for use of public facilities by people with private health insurance:

In Brazil, Chile and Ireland, a significant share of people covered by private health insurance continue to use public facilities. The use of public facilities by those with private health insurance is permitted by law, but in Brazil and Chile the compensation that private insurers are supposed to pay public facilities has been difficult to enforce (Diaz et al. and Ettelt & Roman-Urrestarazu, this volume), and is now being sought through the courts in Brazil. In Ireland, private insurers have never been charged the full economic cost of the use of public hospital beds by privately insured patients, although this anomaly is beginning to be addressed (Turner & Smith, this volume).

Migration of health professionals from public to private facilities where demand for private facilities is sustained by private health insurance:

In Kenya, the vast majority of doctors work in private facilities. In South Africa, the rate of doctors per 100 000 people is more than five times higher in the private sector than the public sector (McIntyre & McLeod, this volume). This drain on human resources can have major implications for the quality of care in public facilities.

Without private health insurance, the demand for private facilities would be hugely diminished in both countries. In spite of this, a fragmented private health insurance market has not been able to exert leverage over private health care providers. As a result, private insurers have responded to having to pay the very high prices charged by private hospitals in South Africa (Reference Lorenzoni and RoubalLorenzoni & Roubal, 2016) by shifting costs onto subscribers through medical savings accounts, eroding the quality of private health insurance coverage and adding to fragmentation (McLeod & McIntyre, this volume).

Another consequence of the growth and power of private facilities in South Africa and the associated imbalance in human resources and inflation in health care prices has been to make a genuinely national system of health insurance seem unduly expensive if it must purchase services from private facilities or attract staff to work in public facilities (McIntyre & McLeod, this volume).

Failure to align provider incentives leads to increased waiting times for publicly financed treatment:

In countries like Germany, Ireland and Israel, doctors permitted to work in both sectors face strong financial incentives to prioritize private health insurance-financed patients, for example, being paid more to treat people with private health insurance or when working in private facilities, which has increased waiting times for publicly financed patients. Although this has not been such an issue in Germany, where waiting times are not significant, it has been problematic in Ireland, where waiting times are the main reason for purchasing supplementary private health insurance, and in Israel.

The problems in Ireland stem from the fact that nearly half of the population has supplementary private health insurance, which is high by international standards. The large size of this market, encouraged not only by long waiting times for specialist treatment but also by extensive tax subsidies and (more recently) financial penalties for those who fail to buy private health insurance before the age of 35 years, exacerbates inequality in timely access to health care.

Indiscriminate tax subsidies for private health insurance:

Inequality in access to health care and fiscal pressure are intensified by indiscriminate use of tax subsidies to encourage take up of private health insurance, especially tax subsidies applied to marginal tax rates, as in Canada, Ireland before 1995 and the United States, which increase as people pay higher rates of tax, meaning wealthier people receive the highest tax subsidies and the poorest people may not receive any tax subsidy at all. France is the only country covered in this volume to target tax subsidies for voluntary private health insurance at poor people.

The use of tax subsidies has had a particularly marked effect on the availability of public funds for health care in Brazil and South Africa, where tax subsidies for private health insurance amount to around 30% of federal government spending on health (Brazil) and around 30% of all government spending on health (South Africa), even though private health insurance covers only a fraction of the population (24% in Brazil and 16% in South Africa) and is heavily skewed in favour of the richest people in both countries.

In Australia and Ireland, tax subsidies for private health insurance have also been substantial in relation to public spending on health, and analysis has shown that these subsidies are not only inequitable but also an ineffective and therefore inefficient means of relieving pressure on public hospitals and reducing waiting times for publicly financed patients (Hall, Fiebig & van Gool and Turner & Smith, this volume).

Tax subsidies are shown to be particularly inappropriate in markets for supplementary private health insurance. To the extent that tax subsidies encourage the growth of such markets, they also ensure that negative spill-over effects are more pronounced.

Finally, markets for private health insurance often result in other spill-over effects, which may be less tangible or quantifiable than the skewing of public resources but can have important and lasting consequences. These include the following outcomes.

Limited transparency and the associated increase in transaction costs for governing bodies and people facing multiple health insurance options. In the Netherlands, a dual system of public and private coverage was deemed to be cumbersome and was eventually abandoned, but Chile, Germany and the United States have not yet managed to make the transition to a unified universal scheme. In Egypt and Israel, some households have triple coverage.

Significant capacity and resources deployed to oversee and regulate market actors who are often recalcitrant, sometimes fraudulent and frequently litigious. Government efforts to regulate private health insurance have encountered legal challenges in many countries, including Chile, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United States.

Time and energy spent debating issues that would not arise in the absence of powerful private interests. One of the most frequently raised questions is whether private insurers should play a role in providing publicly financed coverage in addition to private health insurance, which has dogged policy debates about moving towards universal health coverage in almost every country in this volume (most recently in Chile, Egypt, Germany, India, Ireland, the Netherlands, South Africa and the United States).

Lessons from international experience

The countries in this volume show great diversity in the role that private health insurance plays in health systems and in the size and functioning of different markets. In spite of such diversity, it is possible to identify patterns across countries and lessons for policy-makers thinking about establishing, expanding or addressing problems in a market for private health insurance.

Private health insurance rarely lives up to the expectations set out at the beginning of this chapter: in essence, that it can be used to relieve pressure on government budgets and enhance health system performance. An overview of the history, politics and performance of some of the world’s largest markets for private health insurance reveals a disappointing picture. While private health insurance benefits some people – generally those who are already relatively advantaged – it often has negative consequences for the performance of the health system as a whole, even when its contribution to spending on health is small.

Common problems with private health insurance include:

an inability to fill gaps in publicly financed coverage and reduce out-of-pocket payments in the vast majority of countries globally, demonstrating limited potential to improve financial protection at the level of the health system;

inequality in access to health services between people with and without private health insurance as well as between those with private health insurance; because voluntary private health insurance is systematically more likely to be bought by people in higher socioeconomic groups, the larger the market, the more visible and less acceptable this inequality is likely to be;

the absence of incentives for private health insurance to enhance efficiency and quality in organization and health service delivery in most countries, combined with fragmented purchasing power, means very few private insurers engage in strategic purchasing; in some instances, this pushes up prices in the wider health system;

a tendency to add to fiscal pressure, particularly where boundaries between public and private coverage are not clearly defined or enforced, incentives are not aligned across the health system and tax subsidies for PHI are indiscriminate; as a result, financial and human resources are drawn away from publicly financed coverage to the benefit of people with private health insurance; and

other less obvious effects such as an increase in transaction costs due to limited transparency; the capacity and resources required to oversee the market; and the time and energy spent debating issues that would not arise in the absence of private health insurance.

Many of the problems associated with private health insurance can be attributed to failure on the part of policy-makers to recognize and manage what are essentially predictable risks; predictable because they are clearly set out in economic theory on market failures in health insurance. History and politics have also posed a challenge to effective public policy towards private health insurance, resulting in struggles to ensure adequate oversight of the market and mitigate negative spill-over effects.

Learning from international experience, policy-makers can try to ensure that private health insurance contributes to attaining policy goals through:

clarity in national health financing policy frameworks about the role of private health insurance in the health system;

better understanding of the way in which private health insurance affects health system performance: anticipating predictable risks and likely problems should result in a lowering of expectations about what private health insurance can achieve at health system level; and

better oversight of private health insurance: this requires willingness and capacity to set and enforce clear boundaries between public and private coverage, align incentives across the health system, regulate for financial and consumer protection, and carefully monitor the market.

Policy-makers will benefit from acknowledging from the outset the very limited extent to which a poorly regulated market can enhance health system performance; paying attention to the risks inherent in creating new actors and institutions that may be difficult to direct and impossible to dismantle; and recognizing where a particular policy design reflects history and politics more than informed choice. For example, the countries that opted to establish national health insurance using employment-based private schemes did so for historical and political reasons rather than technical considerations. In today’s context, taking this route would not be an optimal pathway to universal health coverage. Similarly, giving people the ability to choose between public and private coverage – perhaps the most egregious policy design of all – was not the outcome of a desire to foster choice and competition in Germany or the Netherlands but of historical decisions reflecting the needs and circumstances of a very different time. In both countries, the difficulty of mitigating negative effects has been exacerbated by politics, as seen in strong and effective opposition to change from health care providers, private insurers and people with private health insurance. Chile’s decision to opt for a policy design that was already causing problems elsewhere (and soon to be abandoned in the Netherlands) reflected politics too: an ideological belief in the value of choice and competition.

The experience of these and other countries suggests that it is challenging to address negative effects once they have begun to be visible. Even when there is clear evidence of public policies that create or perpetuate inequality and inefficiency (indiscriminate tax subsidies, for instance, or incentives encouraging providers to prioritize people with private health insurance) some governments have been reluctant to take corrective action due to lobbying on the part of private insurers and health care providers or for fear of antagonizing the relatively wealthy and influential people most likely to benefit from private health insurance.

Finally, it is important to be aware of how frequently the interests created by private health insurance have obstructed the expansion of publicly financed coverage. Having to give thought to whether private insurers should play a role in providing publicly financed coverage has not only complicated policy debates about universal health coverage in many countries, it has also slowed national progress towards this goal.