What Counts as Facts?

so there is a factual story about a project that has huge potential and can be developed without having major impacts and to bring about many benefits to Greenland’s society. Then there are rumors, there are myths that are designed to cause people to be scared and concerned and they are two different things. We want to continue to be able to educate people so that they can be able to understand the project in a factual sense and not in a sense that is removed from science and the facts

With these words John Mair, CEO of Greenland Minerals, at the hearing on the Kuannersuit project in South Greenland, Narsaq on 9 February 2021, answered a question about whether the town of Narsaq will end up having to be evacuated if the mine is launched. The questioner found that two very different stories about the mining project were dividing the population: a story where uranium plays a big role and where there is talk of the town being evacuated, and another story where uranium plays no role, and the mine will have no environmental consequences. In other words, the questioner from Narsaq wanted to know which story to believe. To the citizens of Narsaq the two storylines about saving or destroying the local community were conflicting (Bjørst, Reference Bjørst, Fondhal and Wilson2017). In Mair’s response, one of these narratives was equated with rumors, myths, scare campaigns, and non-factual information (see quote), the other with scientific facts. The part of the population that believed in rumors needed to be educated – a task that the CEO argued the company had taken on. Thus, Mair constructed and mobilized an opposition that worked as an organizing mechanism for producing, categorizing, and understanding voices.

Mair himself was clearly affected by emotion when he made the above statement at the end of a two-and-a-half-hour-long consultation meeting. It was not the first time he answered these kinds of questions. Since the beginning of the project development, the coexistence with the active open-pit mine has been questioned by some of the local citizens (Bjørst, Reference Bjørst2016; Hansen & Johnstone, Reference Hansen and Johnstone2019). At this point during the event, Mair was tired and clearly annoyed. The time difference to Australia also had to be taken into consideration (he participated via an online Zoom call). Even on a deeper level, however, Mair’s own argumentation was marked by emotion. By equating the mining project with “potentials” and “benefits” to the Greenlandic society, Mair evoked hope and optimism for future happiness, both for the individual and for society as a whole. It was indeed a prosperous future that the Greenlanders would block if they opposed the mining project. Yet, he took the right to define emotion as something that was neither associated with him nor the narrative he represented but only the party opposing the mining project.

The opposition between facts/support of mining versus emotions/resistance to mining is a firmly established rhetorical figure in conflicts concerning extractive industries (Sejersen & Thisted, Reference Sejersen, Thisted and Nord2021). In the hegemonic discourse on mining and extraction, financial gain is equated with facts, while taking into account “softer” values such as well-being and ecology equates to “emotion.” Inherited from a centuries-long European discourse on enlightenment, there is a consensus that reason ranks above emotion. To a wide extent, social scientists (e.g., Febvre, Reference Febvre1941; Durkheim, Reference Durkheim2008 [1912]; Elias, 2010 [Reference Elias1939]) have promoted a perspective on emotion as a kind of instinct that at all times threatens to overwhelm man and take power over intellect and reason. Society and socialization must therefore undertake to tame impulses and desire, with the intention of curbing barbarism and ensuring enlightenment and progress (Vallgårda, Reference Vallgårda2013). Thus, there is a vast discursive power associated with the right to judge what can count as reason and what must be dismissed as emotion. Therefore, an essential part of getting control is to gain the power to define what counts as facts. To get the facts right is only the next step. An obvious topic for a humanities-based approach to mining and extraction is to take a closer look at such speaking positions. In previous work, we have argued that instead of accepting the prevailing discourse that emotions should be seen as irrelevant to the issue of extraction, we must analyze how emotions are included in the debate and with what effect (Bjørst, Reference Bjørst2020; Thisted, Reference Thisted2020; Sejersen & Thisted, Reference Sejersen, Thisted and Nord2021; Thisted, Sejersen, & Lien, Reference Thisted, Sejersen and Lien2021). Hence, we ask: What is the significance of the affective, which is usually excluded from the analysis of mining?

This chapter focuses on the consultation processes in Narsaq, South West Greenland in connection with Greenland Minerals’ mining project in Kuannersuit, located approximately seven kilometers away from the town. According to the Mineral Resources Act (Naalakkersuisut, 2009), the consultation meetings are mandatory when the environmental impact assessment (EIA) and the social sustainability assessment (SSA) are made available for public consultation. The Act states in §87c that: “[d]uring the consultation period, the Government of Greenland must conduct public consultation meetings in towns and villages particularly affected by the activities” (Naalakkersuisut 2009; 34). Apart from this, the Mineral Resources Act does not give a lot of information about the format of the meetings. Minutes must be taken, and on the Government of Greenland web page it is promised that all questions, answers, and comments will be included in the White Paper and thereby form part of the basis for the Government’s decision. If a company wants to pursue mining in Greenland the process of engagement appears quite transparent, straightforward, and with appropriate time and space allowed for legitimate voices (Sejersen, Reference Sejersen, Gad and Strandsbjerg2018). Hence, as an inherent component of the mining project apparatus, the public hearing in Narsaq had to take place.

The hearing was one step in a long chain of sequential procedures driving the project forward. The hearing process was choreographed as questions and answers, where persons “outside” the project (like NGOs, local people, stakeholders etc.) could ask questions to institutions “inside” the project (like the company, authorities, experts etc.). This hearing choreography is not universal, and in the Arctic many models have been pursued (Arctic EIA project, 2019) when industrial development was on the drawing table. Since 2010, there have been several public consultation and hearing processes related to potential mining projects in Greenland. According to Ackrén (Reference Ackrén2016), public consultation processes or hearing processes in relation to mining industry projects can be characterized as deliberative democracy processes. However, during and after the public hearings, locals often expressed their frustration over a lack of meaningful involvement, and researchers in the field have criticized the process as well (Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2012a, b; Sejersen, Reference Sejersen2015). Critics have been pointing out the problems with one-way communication, the dominance of one knowledge regime, technical concepts and figures, as well as information not related to everyday life in Greenland.

The Emotional Approach: A Review

Greenland extractivism has constantly been promoted as a pathway to welfare (Hastrup & Lien, Reference Hastrup and Lien2020; Sejersen, Reference Sejersen2020), and many assessments and consultations have been pursued. Public consultation processes in Greenland have been analyzed and described, for example, from the perspective of social science (Aaen, Reference Aaen2012; Hansen, Reference Hansen2014; Sejersen, Reference Sejersen2015; Ackrén, Reference Ackrén2016; Heinämäki, Reference Heinämäki, Koivurova, Broderstad, Cambou, Dorough and Stammler2020; Johnson, Reference Johnson, Coates and Holroyd2020; Nuttall, Reference Nuttall2013, Reference Nuttall, Jensen and Hønneland2015), law (Basse, Reference Basse2014), and planning and engineering (Hansen & Kørnøv, Reference Hansen2010; Olsen & Hansen, Reference Olsen and Hansen2014; Hansen & Johnson Reference Hansen and Johnstone2019). Many of these studies are structured around the question of how local involvement can be pursued in proper and meaningful ways. The critical approach pursued by the authors directly or indirectly lean on normative ideas of what constitutes proper or adequate involvement. Aaen (Reference Aaen2012), for example, uses Habermas’ ideas about democratic legitimacy, while Basse (Reference Basse2014) applies ideas agreed in the Aarhus convention. Merrild Hansen (Hansen, Reference Hansen2010; Hansen & Kornøv, Reference Hansen and Kornøv2010; Hansen & Johnstone, Reference Hansen and Johnstone2019) has pointed at how hearing phases and procedures could be optimized and elaborated in order to improve the integration of local voices. In a historical analysis Klaus G. Hansen (Reference Hansen2014) applies three levels of legitimacy (formal, factual, and public), and concludes that a growing formal political influence in a postcolonial context might create space for an increasing number of voices and a diversity of positions in public debates and in decision-making processes.

The requirement for more disclosure, openness, and transparency is, however, still an issue. Dodds and Nuttall (Reference Dodds and Nuttall2016) criticize how contemporary local experiences and knowledge are erased, silenced, forgotten, or downplayed when mining projects are pursued, due to the fact that the production of technical knowledge becomes so dominant and is taking place in a state formation process, which deterritorializes space. In a similar way, Sejersen (Reference Sejersen2015) argues that the circulation of data and perspectives on mega projects is embedded in an empire of expertise, which in itself makes it difficult to have many voices present at the same time. Sejersen (Reference Sejersen2015, Reference Sejersen, Gad and Strandsbjerg2018) proposes that this particular knowledge regime not only marginalizes some voices but also disciplines the remaining voices in order to make them fit the process.

This body of studies clearly shows that there is a critical focus on how public hearings could be organized in a better way. Our intention in bringing in the theoretical perspective of affect is to supplement these studies with a focus on some of the micro dynamics, where language, time, narrative, and atmosphere play a role. We point at how affect plays a role in setting the stage and how people are making sense of what is going on. The “affective turn”2 in cultural and social sciences (c.f. Clough, Reference Clough2008; Greco & Stenner, Reference Greco, Stenner, Greco and Stenner2008) has had a growing influence, not least because it bridges the social and the biological, which have conventionally been treated as separate analytical objects. Thus, affect theory has brought the body back into the political arena, also in its own right and not just as a background for studies of (mis)representation (Thrift, Reference Thrift2007; Wetherell, Reference Wetherell2012).

Rather than regarding emotions as individual psychological states, social sciences view emotion as social practice, located in interaction. Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s concept habitus, the historian Barbara Rosenwein (Reference Rosenwein2006:15) coined the concept emotional communities in order to explain how emotions are never “pure” or unmediated, but products of experience, shaped by the person’s household, neighborhood, and larger society. Communities are not only based on shared repertoires of interpretation or discourses, as Michel Foucault showed, but also on shared repertoires of emotional practices, which like discourses have a disciplining function (Rosenwein, Reference Rosenwein2006: 25). Like Rosenwein, the social psychologist Margaret Wetherell (Reference Wetherell2012: 52) refrains from specifying the exact relation between emotions and discourses but prefers to see them as interwoven in what she describes as affective meaning-making: “affective assemblages operating in important scenes in everyday life along with their social consequences and entitlements.” Hence, it is through such affective practices that norms, values, discourses etc. become embedded in the individual as a “potential” (Wetherell, Reference Wetherell2012: 22). Wetherell rejects the idea, put forward by many scholars, that discourse should have a taming effect on affect. Rather, discourse makes affect powerful and provides the means for affect to travel and spread from one person to another (Wetherell, Reference Wetherell2012: 19). Following Wetherell, the CEO John Mair’s response cited at the beginning of this chapter can be seen as such an assemblage of discourse and affect.

A situation like this has the character of a practice: a speech act (Austin, Reference Austin1975 [1962]) with the purpose of closing the discussion or keeping it from being understood as political. In her studies of the Greenland mining sector, Bjørst (Reference Bjørst2020), for example, introduces a critical approach toward emotions presented as flirtation around “partnerships” as they play out in the mining sector. She argues that “the political seduction involved works best when it pretends to turn away from the political and focus on future relationships” (Bjørst, Reference Bjørst2020: 5). We will be looking further into this “anti-politics machine” later in the chapter (see section “Disciplining of Voices”). First, we will analyze how this distinction between facts and emotions gives power to one set of emotions but suppresses another. It will be demonstrated how the hearing can be seen as a form of apparatus in which atmosphere and emotions are orchestrated, allowing some emotional practices, while excluding other practices. The concept of atmosphere has become prominent, to the point where Bille and Simonsen (Reference Bille and Simonsen2021) argue that – in order to emphasize the spatial and material aspects of affect – “literature within geography has turned from affect to affective atmospheres.” Bille and Simonsen introduce the concept of “atmospheric practices,” and we will argue that the orchestrating of atmosphere of the hearing can be seen as such practice. Since human beings are not, as Bille and Simonsen (Reference Bille and Simonsen2021: 299) point out, “affective dopes,” but “practitioners of emotions,” an atmosphere is always open, unfinished. The organizers may control the apparatus of the hearing, and they can try to tune the atmosphere through a row of atmospheric practices but in the end, as we shall see, they cannot determine the atmosphere.

Working a Translocal Fieldwork Site

The study’s empirical focus is primarily the public hearing event in Narsaq, in February 2021. In event ethnography, meetings are not isolated events but part of an apparatus (further on this concept later) that could make mining possible. Studying mining takes the researchers to fora and unexpected networks both in and outside local communities. Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Corson, Gray, MacDonald and Brosius2014), who have studied global environmental meetings, describe meetings as an active political space and the atmosphere, scenery, and format of these meetings can influence the understanding of what happens and with what effect (Brosius & Campbell, Reference Brosius and Campbell2010).

The hearing in Narsaq stands out as an important event in the process of public consultation. It was followed by people situated in a number of countries. Because of the corona pandemic, only one hundred participants were allowed in the room. The event was broadcast to all of Greenland, and it was also possible to follow the event online (but with a somewhat problematic access to translation). Our study is thus based on online translocal observations (Rokka, Reference Rokka2010) where our focus was on the broadcasted event itself and the digital traffic it created, mostly on Facebook, which is the most used online platform in Greenland. We have identified the hearing in Narsaq as an important communicative event, since this hearing represents a culmination of the public dispute about the Kuannersuit project (also known as the Kvanefjeld project, named after the mountain). Suddenly, a lot was at stake as a parliamentary election was announced the day before the hearing. It was not only the future of Narsaq that was debated – but the future of all of Greenland and government principles. The many contrasting voices from when Greenland lifted the uranium ban in 2013 until this day were part of the conversation (directly and indirectly). Two different futures were present at the hearing: It was either a future with or without mining in Narsaq.

Narsaq, 9 February 2021: Public Consultation Meeting regarding the Kuannersuit Project

During the hearing, one participant suddenly aired a strong frustration over the answers that were given by the company, experts, and the authorities:

During the public meetings in Narsarsuaq, Qaqortoq and this evening in Narsaq, citizens raise their concerns about the EIAs and the answers have been that there is nothing to worry about. If it is impossible for you to be more specific about the environmental impacts that is a source of concern for the citizens, I sense that some feel or respond to me that they are questioning the credibility of the assessments. How come that no one addresses the concerns on the basis of the potential impacts.3

The statement resulted in applause from the audience. From the speaker’s point of view the procedures do not carry the legitimacy that they are claimed to have. Trust in the system is not obvious, and the person pointed to the inherent problem of the particular system: It does not have the community as its central focus but rather the mining project.

Recurrently, the questions showed distrust: Have they monitored everything in detail? The distrust is glued to two different understandings of research: one that sees research as inadequate because it does not understand the locality in detail, and a second that sees research as based on reductionism because it deals with “reality” as if it were a laboratorium, where elements (like the wind) can be turned into a solid factor, that is fed into a scientific system of developed causalities. One participant among the audience glued mistrust to the company itself, by putting focus on the intentions of the company: “I know you are only here because of the money … Do you plan to make the community pay or do you intend to leave our country quietly?” Again, the audience applauded. By bringing the motif of the company into the conversation, the person also addressed a particular understanding of the moral economy of the mining project.

This strategy of dismantling trust touched the fundamental understanding of the company as having mutual interests with the community. Furthermore, it produced affects linked to concern and anti-sociality. The company’s positive arguments about the mine’s contribution to the economy of Greenland as well as the global green transition were put in a shadow. All the good that the company wanted the mine to signal was challenged by part of the audience. One opponent to the mine argued that control of the mining activities had to be pursued by Greenlanders. Another participant was worried for her health: “Can you guarantee me that my health will not be affected? Yes or No?” The answer from the expert was a “yes” if the data and the models were correct and if proper control was implemented. To this response the citizen replied that “one feels that if one asks direct questions then the answers are always very vague. I do not feel comfortable, the project makes me worried. Therefore, I have to ask if I will be affected.” Applause from the audience.

Kell Svenningsen from the authorities guaranteed that the project would be stopped if the limits were crossed. The concern about health was underlined by another participant who borrowed examples from negative mining experiences in other parts of the world. The audience applauded. By situating the future Narsaq mine in a global space of existing mines this person opened up a possibility to destabilize the apparatus that isolated and contained the local project and protected it from comparative global perspectives (Sejersen, Reference Sejersen2015).

Organizing Affective Life at a Citizens’ Meeting

The meeting was held in the Narsaq assembly hall. The setting of the meeting was handled by a moderator appointed by the Government of Greenland, in line with the Minerals Act. Present were also interpreters, TV journalists (KNR), and – due to a bomb threat – uniformed police (Brøns, Reference Brøns2021). The framework was thus embedded in the debate culture that forms the basis of liberal democracy, where a precondition is that everyone can speak, and all voices can be heard. Public hearings on such projects, which can be expected to intervene decisively in citizens’ future everyday lives, are, however, a special genre within liberal democracy, not least because they are most often arranged by the project company (Hansen, Reference Hansen2014).

Public hearings may be events in a long chain of formal engagements of different characters and formats. In Foucault’s terminology, such an institution, embedded in a network of discourses, actors, genres etc. is called an apparatus (in French: dispositif). An apparatus may configure how temporality, space, agency, knowledge, and context are to be approached and performed. Hence the apparatus has a disciplinary impact on epistemology and ontology. Foucault characterizes “apparatus” as always being inscribed in a game of power and certain knowledge coordinates. Homi Bhabha (Reference Bhabha1994: 70) talks about the various colonial discourses as an “apparatus of power.” Apparatus, however, should not be understood as a passive instrument of observation but rather as material-discursive practices that produce differences and demarcations and hence phenomena (Højgaard & Søndergaard, Reference Højgaard, Søndergaard, Brinkmann and Tanggaard2010: 323). Through these practices an apparatus can constitute specific intra-actions, which results in agential cuts (Barad, Reference Barad2007: 155; Bjørst, Reference Bjørst2011: 72). In other words, agency is part of an inter-action and an enactment – not only something you have or do (Barad, Reference Barad2007: 214). Karen Barad writes the following about agency: “Agency never ends; it can never ‘run out’. The notion of intra-actions reformulates the traditional notions of causality and agency in an ongoing reconfiguring of both the real and the possible” (Barad, Reference Barad2007: 177). The apparatus influences what is legitimized as the right kind of knowledge about mining in Greenland.

According to cultural-political geographer Ben Anderson (Reference Anderson2016) the organization and mediation of affects is part and parcel of any such apparatus. Atmospheres are “spaces ‘tinted’ by the presence of objects, humans or environmental constellations … They are spheres of a presence of something, of its reality in space” (Böhme, Reference Böhme1995: 33, quoted from Anderson, 2016: 151). Due to their intangibility, atmospheres always remain open and ambiguous (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016: 156), always in the process of emerging and transforming (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016: 145). The organizers of a meeting may try to “tune” the space and control the atmosphere, but this does not ultimately predict or determine the outcome, since an atmosphere is always translated into individual experience through encounters (Anderson, Reference Anderson2016). This becomes extremely visible in this case, where the meeting was carefully staged in order to tune and maintain an atmosphere of peace and order, good governance, trust, and security, yet it ended up in anger, frustration, noise, and miscommunication.

First and foremost, the Narsaq hearing was framed by the prepared agenda, which appeared on one of the first slides in a power point presentation. The agenda was presented as the first item by the moderator. The moderator also instructed the audience in detail on how to behave during the meeting, in particular as to when to ask questions (after the three speakers had delivered their presentations), how to ask questions (which had to be asked in advance, during the break), how many questions to ask (only two each), and within which areas to ask questions (it was okay to address issues related to environment, society, and health but not to issues related to politics, husbandry, and fauna. It was, however, emphasized that all questions were welcomed if they were put in writing on a particular website). Thus, the moderator not only handled the meeting but also played an important role in the orchestration of feeling and atmosphere. With body language, facial expressions, and voice, he exuded calmness and control.

The fact that the entire first half of the meeting was occupied by three long informative speeches was the most crucial step in terms of orchestrating the atmosphere of the meeting. First, Jørgen T. Hammeken-Holm from the Ministry of Mineral Resources presented how the whole mining assessment and consultation process is divided into phases with fixed rules for pretty much everything in each phase. Next, Johannes Kyed from Greenland Minerals reviewed how the project will contribute to solving Greenland’s economic problems, while at the same time being a huge help to the global climate as the transition to electricity will reduce CO2 emissions. According to Kyed, problems regarding the mine, such as dust problems, disposal of waste (tailings) etc. have been thoroughly investigated – and solved. All calculations showed that there will be no risks for public health or the environment. Thus, Kyed created a chain of equivalence among the Kuannersuit project, economic opportunities, education and jobs, economic independence, and global green transition. Failure to start the project would consequently result in the absence of all these promising possibilities and lead to the situation described as “Dødens gab” (Death’s gap), indicating the gap between expected revenues and expenditures in the state budget (Rosing, Reference Rosing2014). The question in this study is not whether this is true or false, but how such statements frame and produce emotions and voices. Both statements glue good emotions to the mine by upscaling the effects of Kuannersuit. Consequently, a person’s critique of the mine makes the person a killjoy that is unable to see the benefits to the common good, locally, nationally, and globally (Thisted, Reference Thisted2020).

In fact, the third speaker, Christian Juncker Jørgensen from the Danish Centre for Environment and Energy, expressed several reservations, as the EIA-report concludes that extraction without measures to limit environmental impact will lead to extensive pollution. Likewise, the EIA report concludes that further studies should be carried out in a number of areas. Jørgensen also emphasized that staff must be hired who can monitor compliance with regulations once the mine is in operation. However, these reservations were expressed in an academic language with lots of subjunctive constructions and adverbs, which made translation difficult. With its factual, scientific style, the third presentation was thus adding to the atmosphere of good governance, professionalism, and authority associated with scientific discourse (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1992; Baker, Reference Baker2006), inspiring trust and confidence, even though the presentation touched on sensitive risk issues.

The atmosphere of security, trust, and good governance, which was promoted inside the hall, was counteracted by a demonstration taking place outside the hall. The demonstration could not be seen on TV, and it was completely ignored by the moderator, emphasizing that only disciplined voices should be heard. Nevertheless, the demonstration outside could be heard very clearly inside the hall and on several occasions drowned out the meeting itself, so that the interpreter had difficulty translating. Outside, there was an atmosphere of anger, indignation, and rebellion, driven by a sense of unity and community. Slogans were shouted rhythmically, alternating with the protest movement’s song against uranium mining. Obviously, the demonstration outside had the intention of disrupting and undermining the disciplined atmosphere that was being built inside. The loud demonstration was silently present inside, where some of the participants wore red vests with the yellow anti-uranium logo and the text uraani naamik (uranium no).

While the first two speakers took the same position as the moderator and completely ignored the demonstration outside, the third speaker asked the audience “in the red shirts” to go out and ask “their friends” to quiet down, before beginning his presentation. Later, as the music outside drowned out his speech, he suggested that the audience started dancing. In such moments, a crack occurred in the otherwise sharp separation between the two spaces: inside and outside. The crack revealed the strongly opposed emotions that prevailed around the subject. As opposed to the emotional meaning-making represented by the first two speakers especially, the participants in the demonstration outside invested hope for the future in stopping the project. As demonstrated by the red vests with the yellow anti-uranium logo, this opinion was shared by a large proportion of the participants inside the room.

This contradiction became even clearer in the second half of the meeting, where the audience was allowed to ask questions. Despite the fact that all panelists maintained a matter-of-fact, friendly, and accommodating tone, even when exposed to direct attacks from the questioners, the atmosphere in the hall became more and more strained – maybe even hostile in some parts. People asked questions but did not feel they were getting any real answers. In particular, the fact that there was no possibility to follow up on the questions after the answer from the panel aroused frustration. A woman tried to code-switch from Greenlandic to Danish in order to address the Danish-speaking panelists directly, avoiding the tedious translation. However, her intervention was ignored, as her remarks were translated anyway and answered in the same neutral tone as all the other questions and remarks. Even when a person asked if the company would demand compensation if the citizens succeeded in getting the project closed, the answer he received was a long account of the usefulness of the consultation process. Paradoxically, in the logic of the mining apparatus, even the most critical questions help to create an atmosphere of good governance, because all questions will be heard and answered. As simply stated by John Mair, “We [Greenland Minerals] use best practice!” Or as stated by Jørgen T. Hammeken-Holm, “We [Greenland] have the world’s best Minerals Act!” The mining project and its legitimacy, indeed, took center stage and overshadowed any critical questions.

Seen from one perspective, it appears as if the demonstrators outside were undermining the democratic process (i.e., the “system” itself) by making it difficult for the speakers to be heard. From another perspective, it can be argued that they rescued the democratic process, because no room had been created for divergent voices in the mining apparatus inside. In fact, the citizens were trying to live up to the requirements that the Minerals Act places on them as active and co-responsible citizens. The constant flow of publications issued by the Greenlandic government regarding the extractive industries and large-scale projects has repeatedly emphasized the importance of citizens contributing their local knowledge: “The public can possess knowledge of practical conditions (e.g., weather and road conditions) that improve a raw material project or minimizes the inconvenience to those citizens who live close to the mine” (Naalakkersuisut, 2013: 6). For example, a citizen opposed the EIA-report’s statement that there is thirty-one hours of southern wind per year in the Narsaq area. The citizen pointed out that in the period in which the hearings had been held alone, there had already been thirty-one hours of wind from the south. According to this citizen, the equipment that makes the measurements is set up in a place where there is often no wind, even though there are storms everywhere else. The statement was met by a very long and very technical answer that did not seem to contain any clarification. Nevertheless, the moderator concluded that an answer had now been given and proceeded to the next question.

Thus, the meeting ended in an atmosphere of anticlimax, without the parties having approached each other or obtained any clarification of the issues on which the meeting intended to shed light. This observation was repeated by the participants on social media and interviews given to Danish and Greenlandic news media. Also, the absence of political representation to discuss this as more than a technical challenge left most questions still to be answered.

Time and Legitimacy

Time and its production are a key part of the apparatus of mining hearings. The premise is that the mining company expects and performs mining as something that will take place in the near future. Thus, at the point when hearings take place it is still very unclear whether a project will proceed. Nevertheless, the temporality presented at hearings is inscribed in a game of power over when and if the project can proceed. Zooming in on the presentation of Johannes Kyed from Greenland Minerals, any assumption about a possible contradiction between outside businessmen, scientists, and local Greenlanders is counteracted by his presentation in Greenlandic. Kyed (who is from South Greenland himself) reminded the audience about his own engagement since 2008, the different steps in the project and the urgency of the global green transition, Greenland’s economy, and the jobs in Narsaq. He illustrated the process since 2007 with PowerPoint slides in order to emphasize what he understood as a long timespan. In one of the slides the headline was “Societal gains,” illustrated with a graph showing the prospects for Greenland’s national economy to combat Greenland’s “Death’s gap” followed by the upbeat invitation: “We can close the gap in Greenland’s economy!” Thus, Kyed constructed a collective “we” made up by a united society: the Greenland Self Government and Greenland Minerals. However, this upbeat version did not align with the general atmosphere in the room, where most of the audience had their arms crossed and sparsely applauded his presentation.

Kyed was trying his best to evoke an affective community that, according to his presentation, was formed back in 2008 as the first meetings started. The creation of this timeline also evoked an image of Narsaq as a community with long-term involvement and thus also responsibility and moral obligation to the project. The presentation represented the local community as part of the temporality of the mining project, and the division of labor was described in the following way: “At the first meetings we as company facilitated and you were involved in back, and it was expressed that the work needed to be done with the most value [for society].” The argument seems to be that the company had been working for the community that along the line had assigned it a specific task (i.e., create as much value as possible). In other words, we [Greenland Minerals] just did what you told us to, and more than twelve years have passed – and we kept our part of the deal!

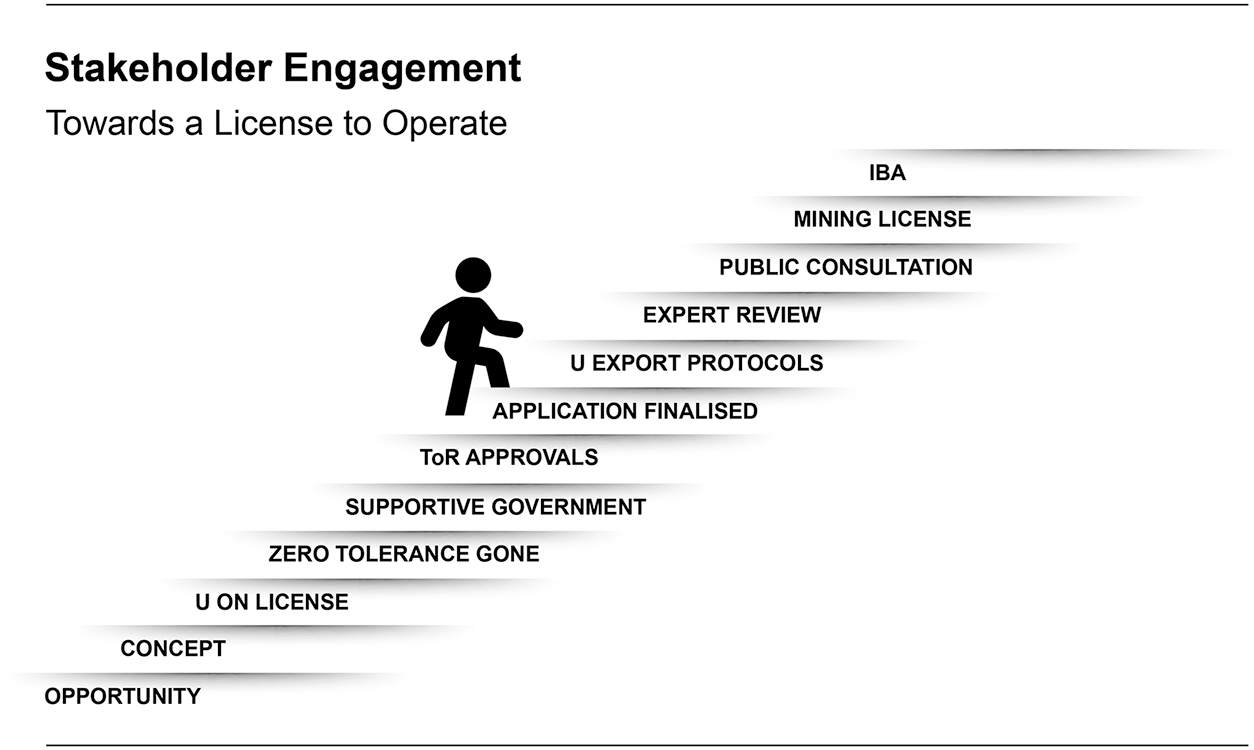

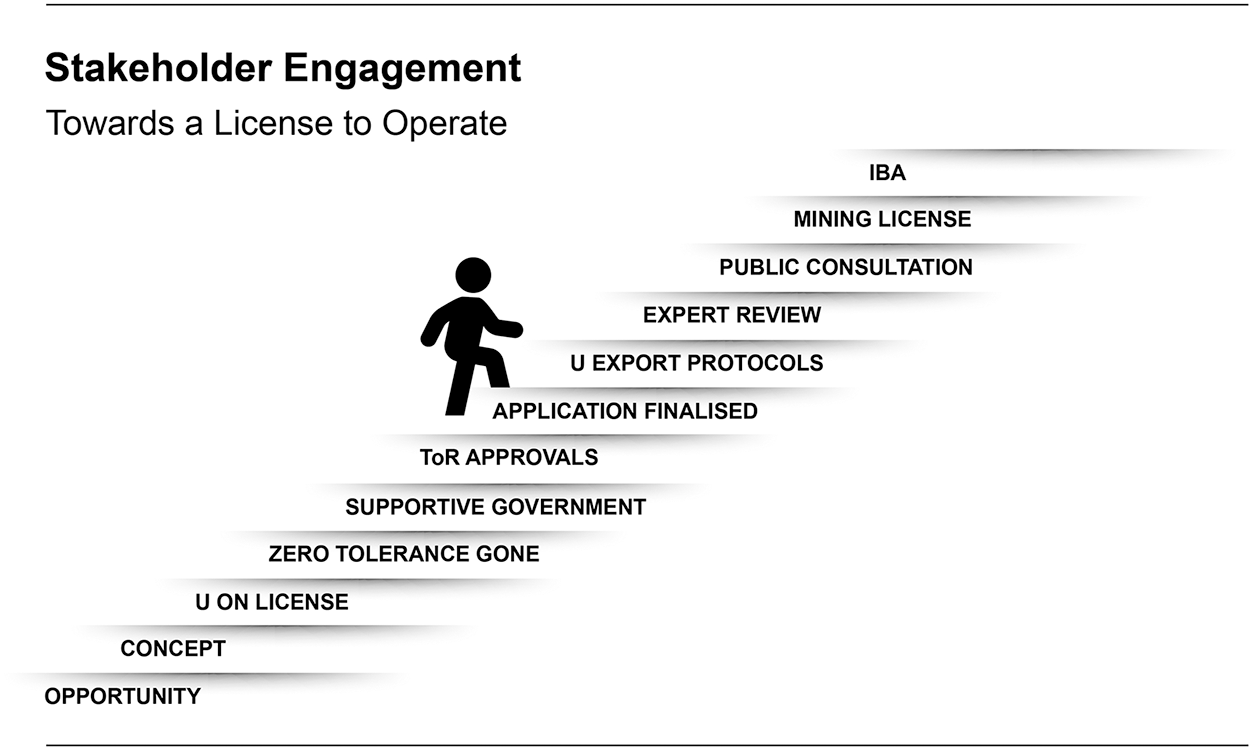

Time becomes an argument in itself. According to the anthropologist Nathalia Brichet (Reference Brichet2018), time is often mobilized in the making of minerals in Greenland. Thinking about time through resource projects is a general trend in how mining is communicated. Kyed’s presentation in Narsaq in 2021 was one of many presentations about the project by Greenland Minerals all over the world at conferences in Australia, China, Canada, Denmark etc. from 2013 to 2021. Forms of temporality are organized in particular ways for the minerals to become valuable and to establish a “license to operate,” as it was already stated on Greenland Minerals’ slides at the mining conference PDAC in Toronto in 2016 (Figure 7.1). In 2016, the slides were not accompanied by a precise year. They only illustrated an upward movement, and through this the realization of the project would emerge. From this slide you get the impression that it is not a long way to go and that all steps on the ladder are equal in workload. There are no hindrances on the way to the top, and the license to operate is part of a natural movement upward. When the company evokes a temporality of evolution it also mobilizes positive affects for this kind of temporality and negative affects to statements contesting timeline progression.

Time is creatively illustrated like a staircase, but according to our analysis, it is more like an endless escalator where more and more stairs appear. The dominant narrative links to an understanding of the process as smooth and that the only way is up with no barriers and setbacks and a process that is disciplined by the apparatus. In 2018, “long-term stakeholder engagement” is illustrated by a timeline going from 2007 to 2017 (Figure 7.2). The fact that citizens have been part of the process for more than a decade is used as an argument legitimizing the project itself. On the slide it stated that “a solid foundation is in place.” Even though they have only moved one step and added yet another step in two years, they characterize this as an “actionable development path forward for 2018” (Figure 7.2). In other words, time itself becomes central in managing minerals and Greenland’s future as a mining country. It is also within the temporal framework that citizens are evoked as particular subjects moving in concordance with the flow and phases of the project “up the stairs,” so to speak. Citizens are allowed to perform and be included in certain ways at each step. In effect, their legitimate room for maneuver can be interpreted as limited (Faurschou, Reference Faurschou2021: 4). If they are not moving forward in the process as laid out it is understood as violating the hearing process and the future of the project.

Figure 7.2 A replica of a slide from Greenland Minerals and Energy Limited’s presentation at the PDAC Convention 2018 organized by the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada.

The hearing shows that mining projects are as much about futures as about mining (Sejersen, Reference Sejersen2020). The futures are creatively scaled in all directions in order to link project activities to certain affects. The company upscaled a future narrative where the metals from the mine would underpin Greenlandic independence and accelerate the world’s green transition. This kind of time- and future-making stood in sharp contrast to the downscaled future narratives of residents in Narsaq, which focused on the health of local people and the wellbeing of the community. Another contrast that emerged was one between the abstract models and systems of the apparatus on the one hand and the concrete experienced lifeworld of people. The focus was on the temporalities of the mine and not the community.

The Disciplining of Voices

Kuannersuit was politically framed and legitimized. These casualties of mining as framed by policymakers situate the mining project in a highly sensitive arena, which has been challenged (see, e.g., The Committee for Greenlandic Mineral Resources to the Benefit of Society (Rosing, Reference Rosing2014)). But these highly speculative casualties are translated into “facts” as they are situated on par with other project facts. A highly political question is therefore transferred into what has been cultivated as a non-political sphere. James Fergusson (Reference Fergusson1990) uses the phrase “the anti-politics machine” to describe this rhetorical move. Highly complex political issues and decisions emerge as purely technical and fact-based. The diversity of political voices and ideas is compressed and filtered into the technical rationality of the mining project, which underlines its central position. Voices at the hearing are thus disciplined to think in a particular way: Their complex concerns and hopes about the small and big futures must have the project as a central driver.

The mining project is the only future horizon to navigate, and it is isolated from other alternative futures. Therefore, statements (or rather questions and answers) are disciplined, shaped, and tamed accordingly. Highly political matters are turned into a simple exchange of “information” and “facts.” By pursuing a question/answer configuration of the event, the mining project itself becomes the organizing device of thinking about futures, which is a fraught topic in Arctic discourse, locally and pan-Arctic (Wormbs, Reference Wormbs2018). Hence, voices are disciplined to narrow their future-making in particular directions laid out by the project, as manifested in the bureaucratic procedures and rationalities as well as in the avalanche of documents. On the one hand, this reduces complexities and emotional maneuver room (limits thinking about what constitutes a good life in Narsaq), as it only allows certain ways to address the future of the community (ideas, hope, and concerns have to be wrapped in project terms). On the other hand, the apparatus itself that drives the momentum, focus, and legitimization of the process can become invested with emotions. This is indeed an interesting paradox.

In particular, trust seems to be the emotion that is mobilized and invested in the process. During the event, the company, the authorities, and specialists concurrently referred to the requirements laid out in the regulations and standards decided on by the authorities, including “best practice” etc. In fact, the regulation became an argument in itself when answering questions. Technical questions were answered by reference to the fact that procedures (assessments etc.) have followed the regulations and requirements. Thereby, the answer was enveloped in mobilizing trust in the system. “Good,” “security,” “trust,” and “no-fear” were glued to the rules and procedures of the apparatus.

During the hearing, few attempts were made by the company to engage the temporalities of the mine with the temporalities of the community. Because the company solely focused on finding and legitimizing the best possible mining set-up, the company was neither able nor competent to address the imminent question that all residents struggled with: In what way would the community like to protect and transform itself, its values, and its social relations? The cluster of optimism (Berlant, Reference Berlant2011: 23) that constituted the desires attached by the company and authorities to the mining project was challenged by the audience’s infusion of distrust. This affective move – during the event – evoked the relation to the mining project as cruel optimism (Berlant, Reference Berlant2011: 1), where the company’s desire to mine would constitute an obstacle to the community’s flourishing. During the event, the company was unable to create an atmosphere of hope because it worked within the logics of the mining apparatus and upscaled the potential benefits of the mine to such an extent that Narsaq and its residents were turned into means to a goal outside their everyday life.

When residents ask “what is going on?” and “what is going to happen?” it is a process of complex sensemaking that draws on a multitude of affects and also takes place outside the formal process of the mining apparatus (Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, Reference Weick, Sutcliffe and Obstfeld2005). In a critical review of Greenlandic hearing practices and structures, Aaen (Reference Aaen2012) points out that many of the problems at the hearings emerge because the Greenlandic authorities have not been clear about what they want to achieve. However, Greenland’s Mineral Strategies are actually very clear with respect to the purpose of the hearings. The hearings are supposed to create goodwill toward the mineral resources company and to boost and smooth the process for the mining companies (Naalakkersuisut, 2014, 2020). This further supports Aaen’s conclusion that hearings easily become a proforma activity that must be overcome in order for the companies to move forward in the application process. We agree with Aaen (Reference Aaen2012: 14) that this is probably in reality the biggest barrier to meaningful engagement of the public. Aaen (Reference Aaen2017: 93) therefore suggests that the central question about “What is going on?” must, to some extent, be answered from the point of view of the social. Fundamentally, this means that the project should adapt to the lifeworld of citizens rather than require the citizens to adapt to the project.

The Significance of the Affective in the Analysis of Mining

By using an affective analytical approach in understanding extractivism we have demonstrated how emotions are always present, even when the opposite is claimed. Affects and emotions emerge as essential social drivers within planning, advocating, modifying, or banning extractive projects. The analysis has shown how affects are used productively to evoke legitimacy and trust. We have shown how the orchestration of atmosphere and the disciplining of voices hindered a meaningful conversation with and integration of local citizens. Hence, such an analytical attention opens up the black boxes of the mining apparatus, in this case the part belonging to the consultation process.

Our affectual analysis opens up a number of points of attention that can be useful to observe carefully in the study and organization of consultation processes:

Events: Public hearings are pivotal contact zones and arenas for affectual exchange. In what ways do the orchestration of hearings work actively to open or close spaces for the legitimate airing of emotions?

Time: Affects and temporality are often closely connected. The orchestration of hearings works actively with time, and by doing so also the emotions that are invested. What hierarchies are installed by the use of temporality and how are voices and imaginations disciplined?

Anticipation: Hearings are arenas to negotiate and anticipate futures. Many emotions are at stake in such future-making. What emotional hierarchies are established, and how do these hierarchies affect meaning-making and imagination?

Facts: Hearings, often, work with a hegemonic understanding of “truth.” Ideas about “facts” and the knowledge regime that legitimizes these “facts” are part of the mining project apparatus. Affects are invested in this praxis of fact-production. How can hearings legitimize perspectives, testimonies, and witnesses that are not easily demarcated as “facts”?

Gravity: The present apparatus has the mining project as the hegemonic center. As a central force it pulls everything in its own direction. In what ways can community futures take center stage in the elaboration of the mining project?

Atmosphere: Hearings are dense contact zones, and much is invested in creating and cultivating a certain atmosphere. How can they be orchestrated in order to recognize a multiplicity of voices?

Transformation: Reflections on mining implementations are closely entangled with discussions about societal transformations. How does the political system secure citizens’ formal opportunity to engage in a qualified discussion of how society should and could be transformed – before the mining project sets the agenda?

Introduction

During a cold winter in a small town in the high North, strange things are happening. In the darkness of a deep underground mine, a mysterious white object is found. This is the starting point of White Wall (Salmenperä, Reference Salmenperä2020) a Finnish-Swedish television mystery drama that premiered in 2020. The eight-part series occurs in a fictional mining town in northern Sweden, site of the world’s largest nuclear waste depository. With its slogan, “Are all mysteries meant to be solved?,” White Wall is a tale of humankind’s limited understanding of nature and the universe. An underground mine located in the high latitude comprises a particularly fitting backdrop for pursuing such a theme, as both the subterranean world and the high North have long been regarded as extraordinary and mysterious places (e.g., Davidson, Reference Davidson2005; Naum, Reference Naum2016; Herva & Lahelma, Reference Herva and Lahelma2019; Herva, Varnajot, & Pashkevich, Reference Herva, Varnajot and Pashkevich2020).

The repurposing of the mine in White Wall brings together the past and future, realities and fantasies, and hopes and fears, and it is within a similar frame that we discuss extractive industries in this chapter. Contemporary perceptions and discourses of Arctic mining are linked to concerns of local and global futures, especially in relation to climate change and its diverse ramifications for the Arctic and the world. The European far North and its resources have long been associated with hopes for a better future through extraction: The discovery of silver from northern Swedish mountains in the seventeenth century triggered hopes of colonial wealth in Sweden, and in the eighteenth century the North became a land of the future where opportunities and riches awaited exploitation. The representation of both the North and the subterranean in White Wall replicates centuries’ old imaginations of the far North and of the underground as mysterious and enchanted worlds, with both ideas converging in the context of mines and mining.

This chapter explores how extractive industries in the Arctic, and more generally, are entwined with such beyond-the-rational conceptualizations and the associated long-running fears and dreams linked to otherworldliness and danger but also treasure and a better future. These ideas and perceptions have a substantial affective potential, which is evident in historical and contemporary discourses of mining and the North. “The North” has been a continuous target of outside projections with various cultural, scholarly, and imaginative constructions since classical antiquity (Byrne, Reference Byrne2013: 7; Herva & Lahelma, Reference Herva and Lahelma2019), commonly associated with features evoking connotations with death, coldness, barrenness, desolation, and remoteness (Hansson, Reference Hansson2012; Ryall, Reference Ryall2014: 122, 124). Alongside this, however, there is also a long tradition of placing visions of upcoming prosperity in the North. For example, the ancient Greeks believed that, beyond the barrenness and cold of the far North, a paradise of peace and plenty existed. The utopian visions regarding the North may have been fueled by the fact that the region was for centuries a source of many coveted treasures: furs, amber, ivory, and magical unicorn horns (Davidson, Reference Davidson2005: 51, 24). This entanglement of underground and Arctic imaginaries thus complicates our understanding of extractive industries in the region, and we demonstrate here that more attention should be paid to such phenomena.

We propose that the controversies around and affective qualities of contemporary mines and mining are entangled with the broader cultural ideas and perceptions of the subterranean. These ideas may not always be readily obvious or consciously recognized, but they nonetheless comprise a “sound board” that can amplify emotional responses to mines and mining. We explore how the cultural heritage of very long-term human entanglements with subterranean and extractive practices feature in perceptions of and attitudes to mining. As few people have extensive first-hand experience of the subterranean world, popular culture – here exemplified by White Wall – plays a central role in reproducing to the wider public centuries- and millennia-old cultural motifs associated with the underground realm. The emotional and affective power of mines and mining – their ability to elicit responses such as fear, excitement, and fascination – goes “beyond-the-rational” (Wright, Reference Wright2012: 1113), which must be accounted for in order to unravel our complex historically and culturally mediated relationship with the world underneath.

Underground Worlds

The story of White Wall begins when, from the depths of an underground mine that is being repurposed as a storage facility for nuclear waste, a white wall is found. The wall turns out to have some kind of agency, and it is questioned throughout the series whether the wall would have been better left undiscovered. The storyline repeats an age-old cultural motif of the underground as a place with supernatural properties, as discussed in this section. Exploring the depths of an underground world can reveal wonders and bring wealth, but the exploration of a forbidden or non-human domain can just as well unleash terror and destruction (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Facing the subterranean world in the limestone mine of Hangelby, Sipoo, 1956.

Rich orebodies linger in a space between imaginaries and reality, with agency-like qualities assigned to them, and having an aura of otherworldliness, similar to how treasures are described in folklore. Treasures are (potentially) material but simultaneously spectral, extraordinary, and otherworldly (Dillinger, Reference Dillinger2011). Both hidden treasures and orebodies are characterized by their great potential accompanied with great uncertainty. Indeed, it is not uncommon to see metals and minerals referred to as “treasures” even in present-day Finnish news articles about mining (e.g., Malin, Reference Malin2008; Ronkainen, Reference Ronkainen2018). By the same token, Norwegian Industry Minister Trond Giske boldly declared in 2010 that “God knew what he was doing when he made Norway,” referring to the minerals located in Norwegian mountains, describing mineral prospecting as a “treasure hunt” (Tønset & Langørgen, Reference Tønset and Langørgen2010, authors’ translation). Treasures embody the human dream of gaining happiness through sudden wealth (Sarmela, Reference Sarmela2007: 452–459). Likewise, metals and minerals today hold a symbolic value beyond their mere material worth through their inherent promise of a better future (Engwicht, Reference Engwicht2018: 263).

Human life and culture have built on and been critically entangled with various subterranean realities and imaginaries for thousands of years. At the same time, however, the subterranean world has been, and still is, a strange and unknown realm that inspires awe, fear, anxiety, and fascination (Kroonenberg, Reference Kroonenberg2013; Hunt, Reference Hunt2019). In this view, it is not by coincidence that there are signs of “ritual” activities documented in relation to caves and other (artificial or natural) openings in the ground, from prehistory to the present. Cave art research shows that underground spaces have been invested with special meaning in Europe since the Upper Palaeolithic (c. 46,000–12,000 BP) for spiritual and cosmological reasons, exemplified in cave art. The Neolithic (c. 10,000–3,300 BCE) marked the emergence of new ways of life and being in the world, which involved increased material and symbolic engagement with the subterranean world (Herva & Lahelma, Reference Herva and Lahelma2019). The discovery of metal-making intensified engagements with the underground world further, and extractive pursuits have been intertwined with major transformations in human culture, cosmology, and society since at least the Bronze Age (c. 3,300–500 BCE). Problematic as the division of prehistory into the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages may otherwise be, it does illustrate the deep importance of metals and, by implication, extractive practices to the human story for a very long time. This was not simply about accessing “better” materials for tools, but metals and metal-making, including the procuring of ores, mediated environmental relations and worldviews, and affected the very organization of societies, including early state formation in the Near East and eastern Mediterranean.

Later still, the introduction of iron brought about further socio-cultural changes, and not least because iron ore was readily available, unlike copper and particularly tin. This significance of iron in huge socio-cultural shifts was to be echoed in the making of the industrial world millennia later. Iron is a particularly powerful material in European folklore from the medieval and early modern periods to recent times: fairies, ghosts, witches, and other supernatural beings fear it, culturally reflecting the power humans can gain over the supernatural and the unknown through potent treasures from the underground. In addition to bringing about myriad social, economic, and cultural transformations, industrialization further marked new scales and ways of engaging with the subterranean world, including, for example, the increased construction of underground infrastructure, which in turn was associated with such metaphysical matters as truth-seeking through excavation (Williams, Reference Williams1990) in Enlightenment antiquarianism.

Modern cultures and lifestyles are built on the products of mining: aircraft, buses, trains, cars, phones, televisions, fertilisers, medical and surgical equipment, water, electricity and gas infrastructure, and the processing of solar, wind, and water energy. All these things need minerals (Taylor, Reference Taylor2014). We are surrounded and supported by products of the subterranean and underground infrastructures that effectively make possible the human world as we know it today. Yet relatively few have first-hand experience of extraction sites, which tend to be inaccessible and invisible in the everyday flow of life (Bridge, Reference Bridge2015). Despite advances in technology and human capability to exploit mineral resources, underground worlds still are and appear alien and unpredictable; they are deeply different from the ordinary human lifeworld aboveground and “cannot be directly visualized, touched, or manipulated outside of excavation or sampling” (Kinchy, Phadke, & Smith, Reference Kinchy, Phadke and Smith2018: 31). Underground mines, for example, are distinctive places where the boundaries between the natural and cultural are mixed and blurred. This is cinematographically shown in White Wall, with the subterranean as a jumble of lights, shadows, forms, and things difficult to distinguish from each other. The subterranean world is presented as governed by laws and processes distinctly different from those aboveground. Even time is experienced differently underground. Like caves, mines can similarly be imagined as “portals, worm-holes between two worlds in which time and space work differently” (Bridge, Reference Bridge2015).

The strangeness and otherness associated with the subterranean – whether natural caves or constructed underground spaces – is not founded only on imaginations of that unfamiliar world, but the bodily experience of them as well: “The physical geography of rock and spaces affects how a human body may encounter and experience caves, shaping sensuous and intimate underground knowledges” (Cant, Reference Cant2003: 68). The peculiar bodily-sensory and cognitive effects of mines are related to the play of light, colours, sounds, material features, sense of time, and so forth, all of which creates a form of “infrastructure of enchantment” (Holloway, Reference Holloway2010) for curious phenomena and experiences that feed miners’ folklore (see, e.g., Hand, Reference Hand1942). Rather than mere anecdotes and “beliefs,” historical and contemporary folklore accounts of the strange subterranean world are better understood as reflecting the complex human relationship with the subterranean, as well as the difficult conditions underground requiring special knowledges and practices.

Besides the peculiar sensory properties of subterranean spaces, the underground has yielded various tangible wonders from crystals, gems, and ores to ancient artefacts, fossils, and human remains – the wondrous wall in White Wall resonates readily with this broader theme. Such finds materialize and solidify many otherwise intangible notions of subterranean otherworldliness. Finnish folklore, for example, contains numerous stories about hidden treasures and instructions for obtaining them, often communicating a moral lesson about the futility of pursuing the unattainable (Sarmela, Reference Sarmela2007: 452–459). The underground also has a transformative effect on things, as seen in alteration of organic matter, changing their appearance or constitution, or devouring them completely. This reflects the dynamic nature of the underground: it “is not fixed, inert, or lifeless,” but “comes to be through interlinked political, economic, cultural, and technoscientific practices and processes” (Kinchy et al., Reference Kinchy, Phadke and Smith2018: 23–24; see also Kroonenberg, Reference Kroonenberg2013).

Importantly, industrialization and modernization have not erased the supernatural from the lived world (e.g., Virtanen, Reference Virtanen and Kvideland1992). Narratives, rituals, and supernatural beliefs continue to haunt engagements with the underground and thus affect extractive approaches and practices. One of the greatest markers of modernity and urbanity, the building of underground railways, first in London from 1863, might have appeared to finally dispel any vestiges of magical thinking in relation of the underground by normalizing being-in-the-underground, or colonizing the underground, through technological achievement. However, as Alex Bevan (Reference Bevan and Bell2019) has illustrated, the London Underground is as susceptible as anywhere to supernatural associations, arising in great part from centuries-old associations of the underground as the realm of the dead and its connotations with hell. Further, classic ghost stories such as E. F. Benson’s In the Tube (1923) have shown that fiction was inspired by the fast-accreting narratives of the eery and supernatural in the urban underground – or, simply, Gothic imaginations were inspired by being in such an environment.

It has been suggested that the dualistic nature of various spirits, such as the both malevolent and benevolent Wild Man in Renaissance Germany, occupying underground mines, has personified the simultaneous danger, uncertainty, and desirability of the mining industry (Asmussen & Long, Reference Asmussen and Long2019: 14, 21). The motif is also known from early modern Sweden, where the “keeper spirits” of orebodies had the same ambiguous nature (Fors, Reference Fors2015). The subterranean is a place of monsters, gods, alien technology, and communities outside normal society, alongside the potential for new worlds and discoveries. Myriad books and films build on ideas of hidden underground places, natural and artificial, and feature magical, supernatural, and frightening elements, ranging from Tolkien’s Middle-earth (e.g., Tolkien, Reference Tolkien1995 [1954–1955]) to Tim Powers’s The Anubis Gates (1983) and Jeff Long’s The Descent (1999), to name a few. Some of these works are “genre” fiction, such as horror, science fiction, or fantasy, but similar themes appear also in mainstream culture, as exemplified by White Wall.

Monumental and Extraordinary

Some scenes of White Wall were filmed in the Pyhäsalmi underground copper and zinc mine in Finland. Pyhäsalmi (Figure 2.2) is one of Europe’s deepest and oldest operative underground mines, although the plan was to close its operations in 2021 (First Quantum Minerals, 2020). The fact that some of the filming took place 700 meters below the surface has been heavily utilized in the marketing of the series. Working in such extraordinary conditions necessitated, according to the director Aleksi Salmenperä, the presence of a psychiatric nurse during the filming in case deep tunnels proved to be too distressing for the cast and crew members (Broholm, Reference Broholm2020). This echoes the special character of mines as operational environments, underscored by newspaper articles stressing the special, mysterious, unnatural, and potentially dangerous nature of working deep underground, which calls for particular safety measures in order for humans to operate there (see, e.g., Koivuranta, Reference Koivuranta2020; Myllykoski, Reference Myllykoski2020).

Working underground poses numerous physical and psychological hazards to people, and managing the non-human conditions hinges, in part, on non-human agents, such as technology. Mines are arenas where entanglements and interaction between humans and sometimes autonomous non-humans, technological or otherwise, are acutely felt and in part produced and mediated by working with mechanical and digital devices (Figure 8.2). This emphasizes the “unnatural” aspect of mines and mining, which resonates with divided and disturbing emotional responses: It is an environment where people must deal with inherent uncertainty and rely on non-humans, whether machines or spirits, not only to be successful but also to simply survive, regardless of whether workers wear “low-tech” hard hats or more “hi-tech” breathing masks (LeCain, Reference LeCain2009: 46–47). Mines have been compared to spaceships: both are highly engineered environments that enable survival and operation in otherwise lethal non-human, or beyond-human, conditions (LeCain Reference LeCain2009: 55). Modern technology is used to give humans superhuman or supernatural qualities so that they can adequately deal with the beyond-human supernature of the underground. In this sense, mining machines comprise an elementary constituent of the “ecologies” of extraction sites, which is obvious in White Wall. A curiously malfunctioning machine sets the plot going, and human–machine interaction is a recurrent motif both in terms of the storyline and aesthetics of the series. People, machines, and underground spaces are often shown in ways where boundaries between them are difficult to identify, which enhances the sense of the extraordinary, abnormality, and the mysterious. In the early modern period, too, mines in northern Fennoscandia were subject to intrigue that revolved around the simultaneously scientific and enchanted nature of technology and the subterranean, and human interaction with them (Naum, Reference Naum2019).

Figure 8.2 A loading machine in a mine.

Another unsettling and emotionally affective aspect of modern mines and mining is their monumental scale. Modern mining is embedded in development ideology, with the image of mining the industry wishes to convey that of “greatness of economic success linked to grandeur of technological scale and high-quality human performance,” often through “repetitive proclamations about the extremely large scale of the technology” (Trigger Reference Trigger1997: 165–166). The sheer scale of mines evokes feelings of awe, unease, and fear in a similar way to other natural and built monuments from Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon to pyramids and skyscrapers (e.g., Nye, Reference Nye1994) (Figure 8.3). Indeed, the admiration and dread that people potentially experience when faced with new and strange technologies has been likened to a religious experience (Mikkola, Reference Mikkola2009: 207). Huge open pits or hundreds and thousands of kilometres of tunnels and galleries underground, alongside monumental piles of waste material and massive infrastructure, also make mines seem like monstrous and constantly changing giants, “dragons” or “tricksters,” not completely controllable by humans (Ureta & Flores, Reference Ureta and Flores2018). Mining may represent the triumph of human control over chaotic nature through technology but underlying this are concerns that this changing giant may get out of control yet, with catastrophic consequences. It is fitting, then, that mines are often characterized as “sacrifice zones,” as Reinert (Reference Reinert2018) discusses in his examination of a prospective mine in northern Norway: Places are destroyed or damaged both below ground and above ground in exchange for the supposed gains that the underground is expected to provide.

Figure 8.3 A monumental “sacrificial” mining landscape in Kiruna.

Mining is a thoroughly technological pursuit, and technology, in turn, has always been subject to wonder and magic, as illustrated by European travellers’ fascination with the extraordinary technology in early modern Swedish mines (Naum, Reference Naum2019) or the present-day “techno-paganism” among ICT specialists (Aupers, Reference Aupers2009). For Gell (Reference Gell1988), technology is indeed a form of magic due to its power to enchant us and thus also provoke emotions. Hornborg (Reference Hornborg2015: 52) argues that “modern technology is magic. It is a specific way of exerting power over other people while concealing the extent to which it is mediated by human perceptions.” Magical thinking is not absent in spaces of modern mining and industry either, but mines can provoke supernatural experiences and narratives (e.g., Hand, Reference Hand1942).

In more concrete terms, Hemminki (Reference Hemminki, Äikäs and Lipkin2020: 213) discusses the continued relationship between metallurgy and the supernatural during industrialization in Finland in the twentieth century and shows, for instance, that factory-made metal objects were thought to possess magical powers and could be used for curing diseases. Indeed, as Aupers (Reference Aupers2009: 171) saliently points out, “technological progress may paradoxically be responsible for the growth and flowering of mystery and magic in the late-modern world.” Technology often works in mysterious ways and affords a sense and awareness of a deeply interconnected (and broadly spiritual) nature of lived and experienced reality. Mines as extraordinary spaces where diverse powers and agents are in operation readily emphasize that the world is not only about humans, but that they co-inhabit it with a host of non-human entities that have diverse influences on human life, ranging from lichen to spectral animals to ghosts and from trolls to spiritual keeper entities of ores that can manifest themselves and be experienced in various ways. In some ways, modern mines with their myriad non-human beings and powers can be compared to the age-old shamanistic ideas of the enchanted underworld.

Magic and Volatility

Early on in White Wall, the viewers learn that the project to create a nuclear waste deposit in the mine has been delayed for some time. There is a pressure to open the facility as soon as possible because the company in charge is running out of money, motivating the site manager to find out the nature of the strange object found underground (the “white wall”) quickly and without publicity. Money, of course, is an important driver in the drama around mines and mining in real life. It is simultaneously enmeshed in contemporary magical thinking: “capitalism and its supporting mechanisms are not often as rational as they made themselves out to be” (Moeran & Waal Malefyt, Reference Moeran, de Waal Malefyt, Moeran and de Waal Malefyt2018: 2; see also, e.g., Hoffman, 1967 on the folklore of Wall Street). One function of magical practices is to manage with uncertainty and unpredictability (see Moeran & Waal Malefyt, Reference Moeran, de Waal Malefyt, Moeran and de Waal Malefyt2018: 10–12), which in turn are integral aspects of both contemporary extractive industries and economies, affected by invisible, mysterious, and volatile forces of the “markets” and the “invisible hand of capital.” Modern money and the markets can seem to behave quite erratically, and indeed have a life of their own and are frequently out of control, which renders them as mysterious as the premodern world with its spiritual powers, which add to the affective dimensions of such megaprojects as mines.

The growth of the finance sector over the 2000s and the increased separation of speculative economies from real economies may be particularly evident in the extractive sector that is heavily dependent on attracting enormous outside investments, which, according to Tsing (Reference Tsing2000: 120, 127), is done through the “self-conscious making of a spectacle.” Capital is conjured through magic, and excitement toward new projects is created with grandiose promises and “manufacturing of drama.” In other words, the projects are made to look better than they are in order to attract finances, which make it difficult to distinguish viable mining projects from unrealistic ones (Tsing, Reference Tsing2000: 120, 127; see also Reinert, Reference Reinert2018). Simultaneously, however, mining projects may have very real and large-scale environmental and social impacts already in the planning stage of mines. This duality between the invisible (or speculative) and visible (or real) worlds can readily create discomfort and thus emotional engagement, whether “negative” or “positive,” with mines and mining, alongside the environmental and aesthetic degradation that comes with them.

Perceptions of mining revolve around fear and hope, associated with notions such as mining bringing salvation to economically challenged peripheral regions or else bringing doom through destruction of the environment, with uncertain or unsubstantiated positive impacts. Through centuries, mining has been seen in negative terms as morally suspicious treasure-hunting driven by greed, as well as a positive force that generates economic and social well-being. The twenty-first century has largely been marked by a moral condemnation of greed, which is now seen as destructive for society, and global companies have become the icons of greed and excess (Oka & Kuijt, Reference Oka and Kuijt2014: 36, 41, 44). For example, a quick Google search offers numerous cautionary opinion pieces where it is suggested that current mining ventures are being driven by greed (e.g., Koskiniemi, Reference Koskiniemi2012; Hartio, Reference Hartio2015; Rutledge, Reference Rutledge2017; Huttunen, Reference Huttunen2018; Widdup, Reference Widdup2018; Prashad, Reference Prashad2019).

Naum (Reference Naum2019) observes that, in the seventeenth century, critics of mining considered it an “unnatural” and “destructive” activity, governed by greed that would cause harmful social and environmental repercussions by “wounding the organic body of the Earth.” For these critics, interfering with the underground world was morally and cosmologically wrong, whereas the proponents emphasized the material and social benefits of mining – industrial work was taken to improve people and their quality of life (Naum, Reference Naum2019: 2–3, 19). The “unnatural” character of mining echoes, to at least some degree, the fear of the strange and unknown subterranean realm and how the greed for harvesting its riches may bring destruction not only through natural causes but also supernatural agency – a theme that has been pursued in modern fiction.

In J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1995 [1954–1955]), the greedy dwarves mined too deep for their desired mithril in Moria, awakening an ancient demonic entity, a Balrog, which in turn results in the annihilation of the dwarf kingdom under the mountain. Similarly, the existence of the entire planet of the Na’vi is threatened by resource extraction in James Cameron’s film Avatar (2009). Mining has come to exemplify the destructive side of modernity, as evidenced by historical and contemporary ruined, toxic, and monstrous landscapes that extractive industries produce. The real and fictional views on the destructive character of mining stem from such concrete phenomena as environmental disasters, social problems, violence, and warfare associated with mining (Ballard and Banks Reference Ballard and Banks2003), but cultural and cosmological ideas about the troubling nature of engaging with the subterranean otherworld are also in play, however vague and subconscious they may be.

While the real and fictive greed for underground resources can have dystopian consequences with potentially supernatural dimensions, the positive views on mining also tend to have an aspect of faith and miracle-work to them. Extractive industries are seen to generate wealth and well-being almost by magic. Mining projects are frequently portrayed, and understood among supporters, as eliciting dream-like expectations of prosperity and a better future, documented among communities of diverse cultural and geographical backgrounds. This has been demonstrated in recent research addressing expectations toward modern mining projects (Filer & Macintyre, Reference Filer and Macintyre2006; Pijpers, Reference Pijpers2016; Engwicht, Reference Engwicht2018; Haikola & Anshelm, Reference Haikola and Anshelm2018; Poelzer & Ejdemo, Reference Poelzer and Ejdemo2018; Wiegink, Reference Wiegink2018). Moreover, it is intriguing that, as Wilson and Stammler (2016) observe in the context of Arctic mining, “expectations tend to be the same, no matter how many times such expectations have been disappointed, or opportunities wasted in other regions in the past” (Wilson & Stammler, 2016: 1; see further Wormbs, 2018). This is perhaps, as Filer and Macintyre (Reference Filer and Macintyre2006: 224) suggest, because there is enough evidence of wealth generated through mining to feed fantasy-like expectations toward new mining projects.