I Introduction

The rule of law – understood as a societal equilibrium in which state and society are bound by law, and in which the state provides an enabling environment for people to enjoy their rights – is considered an essential element to guarantee the development of modern societies. Around the world, however, strengthening the rule of law remains a pending task. Despite the democratizing waves that emerged after the Cold War and multiple advances in the areas of transparency and justice, the world seems to have entered a stage of institutional stagnation and democratic backsliding. In 2019, more than 5 billion people lacked access to justice,Footnote 1 and few countries made significant progress against corruption in the last decade.Footnote 2 Moreover, democracy has been in decline worldwide. In 2021, Freedom House reported the sixteenth consecutive year of democratic erosion and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) institute reported that the level of democracy enjoyed by the average global citizen in 2021 fell to 1989 levelsFootnote 3, which means that the advances of the third wave of democratization have receded.

In response to this crisis, scholars have recently turned their attention to documenting these trends and to examining why democracies are breaking downFootnote 4. These studies have focused on democratic backsliding but have neglected to study rule-of-law backsliding. There are virtually no empirical studies examining this issue, and the existing theoretical sources that discuss it only do so in reference to the European Union.Footnote 5 Although the principles of democracy and the rule of law are closely related, they are not the same. As stated by Shaffer and Sandholtz in Chapter 1, “The issue of democratic governance poses the question of who exercises power. Rule-of-law-concerns examine the question of how’ power is exercised.” More specifically, definitions of democracy are typically centered on free and fair elections (electoral democracy) and on the provision of civil liberties and political rights (liberal democracy). In contrast, definitions of the rule of law focus on compliance with and enforcement of the law, and the imposition of limits on the exercise of power, although there is no consensus on the specific elements to be included in a universal definition. Rule of law is therefore a broader concept than democratic governance and demands a more comprehensive analysis.

In this chapter, we explore whether the rule of law has deteriorated around the world in recent years, and if so, how this shift has occurred and where. We generate indicators using various conceptualizations of the rule of law, including some focused on the imposition of limits on the arbitrary use of power by agents of the state – such as proposed by Shaffer and Sandholtz in Chapter 1 – as well as thicker conceptualizations that include not only the imposition of limits on executive discretion but also the creation of an enabling environment where citizens can enjoy their rights. We then examine the variations in these indicators with a view to unpacking the sources of the rule-of-law backsliding. We also explore whether such backsliding has occurred in countries with high or lower levels of rule of law, and whether this trend is associated with the recent rise to power of leaders with populist or antipluralist tendencies.

It is clear to see that authoritarian leaders may seek to dismantle institutional checks and balances – or dismantle the “guardrails of democracy” mentioned by Levitsky and ZibblatFootnote 6 – in order to restrict fundamental freedoms and weaken transparency and accountability. However, it is not obvious that authoritarian leaders are interested in encouraging particularism and corruptionFootnote 7 or in causing a deterioration in administrative agencies or security and justice systems. Indeed, autocratic leaders have mixed incentives to develop state capacity. On the one hand, state-building can help address citizens’ demands and strengthen the control apparatus. On the other hand, state-building can generate resistance – for example, through the strengthening of bureaucracy – and fuel collective demands for the right to participate in the decision-making process.Footnote 8

To explore these questions, we use data from the World Justice Project’s WJP Rule of Law Index covering more than 100 countries from 2015 to 2022. This dataset contains indicators on various dimensions of the rule of law, including those that capture the limits on the exercise of power by state agents and the limits imposed by the state on the actions of members of society. These indicators’ scores are generated from assessments by the general public and in-country legal practitioners and range from 0 to 1, with 1 representing strongest adherence to the rule of law.

We find that the rule of law has indeed deteriorated in recent years around the world. Aggregate WJP Rule of Law Index scores, which capture perceptions about the functioning of the state and institutional checks and balances, fell in 74 percent of countries between 2015 and 2022, with the decline averaging −3.1 percent This fall, however, has not been homogeneous across indicators. The indicators of fundamental rights and constraints on government powers fell during this period in 76 percent and 68 percent of countries and by an average of −6.7% and −5.1%, respectively. Other indicators’ scores, constructed from disaggregated WJP Rule of Law Index data, tell a similar story. The scores of the indicators capturing the sources of arbitrariness proposed by Shaffer and Sandholtz fell in more than 60 percent of countries. Similarly, scores measuring anti-authoritarianism fell in 68 percent of countries by an average of −5.5%. In contrast, scores under the state capacity indicator, which capture perceptions of the functioning of the regulatory, security, and justice systems, fell in only 56 percent of countries and by an average of only −0.3%. To further investigate the backsliding and examine the countries in which it has occurred, we use cluster analysis of the change over time in the main indicators of the WJP Rule of Law Index. We identify three groups of countries. The first is composed of countries that have experienced a deterioration in all indicators, but most notably in those measuring limits to state power, open government, and respect for human rights, and that already had low rule-of-law levels in 2015. The second group is composed of countries where overall rule-of-law trends have also declined, but less severely. These countries had different levels of rule of law in 2015, although higher than the levels of the first group, and have also experienced considerable declines in the indicators measuring limits to state power and respect for human rights. The third group is composed of countries where most indicators have experienced slight improvements. This group is composed of countries in transition, such as Kazakhstan, and countries with high levels of rule of law located mainly in the European Union.

These results suggest that the rule-of law-backsliding has been incremental and driven by the weakening of limits on state power, as measured by the governmental and nongovernmental checks and balances and the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms, rather than by an acute deterioration in the application or enforcement of the law or in access to justice (except in those cases that have experienced a sharp decline). Furthermore, although significant, backsliding in most countries has been less pronounced, probably due to less severe shocks, greater institutional strengthFootnote 9, economic developmentFootnote 10, state capacityFootnote 11, developed bureaucracy, effective oppositionFootnote 12, free and critical press and civil society, or changes in administration during the period. Overall, our results indicate that the weakening of the rule of law appears to be associated, in part, with an increase in the authoritarian tendencies of certain regimes and, in part, with the rise of antipluralist and populist leaders. Our analysis is limited to the years 2015 to 2022, as the data for previous years is not comparable. Nonetheless, other data sources show improvements in the earlier periods, which may indicate a wave effect, rising in the preceding three decades and then falling more recently.

Our contribution to the literature is threefold. First, our chapter is the first to analyze empirically the issue of rule-of-law backsliding at the transnational level, approaching it from a broad perspective bearing in mind that there is no consensus about the meaning of this concept. Second, our chapter contributes to the debate on the way in which the ascension of antidemocratic leaders affects various dimensions of the rule of raw and, more broadly, to the literature on democratic decline. Finally, methodologically, very few studies have applied cluster analysis to analyze and group different trends across countries. In this regard, our work is closely related to the “democracy cluster classification” index developed by Ristei and Centellas, where the authors use hierarchical cluster algorithms to classify countries according to their regime types and trends in democratic governance.Footnote 13 Our work has several limitations. Our analysis is mostly descriptive and does not explore the causes of the rule-of-law backsliding or the different institutional structures that might explain the cross-country variations. The analysis focuses on national trends and omits subnational variations, which can be important in federalist and decentralized countries. Our analysis is also limited to recent years and uses perception data. In spite of this, the analysis is useful for laying the groundwork for in-depth comparative analysis and case studies.

The rest of this chapter proceeds as follows. In Part II, we explore the concept of the rule of law. In Part III, we describe the data. In Part IV, we develop our analysis. Finally, in Part V, we conclude.

II The Rule-of-Law Concept

The first step in determining whether the rule of law has deteriorated in recent years is to define the concept. Although the rule of law is considered central to achieving a wide variety of social goals –such as promoting peace, justice, and economic development – there is little consensus on what it means, and little literature exploring the notion of rule-of law-backsliding, its sources, or how the rule of law emerges or recovers in environments where it has deteriorated or does not exist.Footnote 14

Across the literature, it is possible to identify two principal conceptions of the term: a formalist, or “thin,” definition and a substantive, or “thick,” definition. Formalist definitions of the rule of law do not make a judgment about the legitimacy or justness of the laws themselves. Instead, they focus on procedure. They focus on whether rules exist and scrutinize whether those rules are followed by all, including the sovereign: “Stripped of all technicalities this means that government in all its actions is bound by rules fixed and announced beforehand.”Footnote 15. In contrast, substantive or “thick” definitions take into consideration certain rights that are seen to be fundamental to the rule of law and incorporate adherence to normative standards of rights, fairness, and equity.Footnote 16

A central element in most of these conceptualizations is that the law imposes limits on the arbitrary exercise of power by the government and other social actors, although the emphasis is usually put on the restraints imposed on the ruler. This approach can be found, for instance, in the working definition offered by the European Commission in 2014 in a communication titled A New EU Framework to Strengthen the Rule of Law, where it distinguished six core components based on various rulings by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU): legality; legal certainty; prohibition of arbitrariness on the part of executive powers; independent and impartial courts; effective judicial review including respect for fundamental rights; and equality before the law. Subsequently, this definition was slightly refined in a 2019 communication, Further Strengthening the Rule of Law Within the Union: State of Play and Possible Next Steps, in which the Commission observed: “Under the rule of law, all public powers always act within the constraints set out by law, in accordance with the values of democracy and fundamental rights, and under the control of independent and impartial courts.” Shaffer and Sandholtz similarly refer to some of these elements in their discussion of sources of arbitrariness and attendant rule-of-law definitions – i.e., application of law to rules, predictability of published rules, fora for bringing challenges, proportionality of means to ends, and reason-giving.Footnote 17

Other conceptualizations have gone beyond this narrow formulation – protection from the sovereign or from each other – to include additional organizational features of a society, such as the existence of an environment in which people can enjoy their rights, use the law proactively to pursue their goals, and secure redress when those rights are violated. This is captured, for instance, in the definition proposed by the United Nations: “The rule of law … refers to a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards.”Footnote 18 A similar approach can be found in the definition used by the World Justice Project (WJP):

The rule of law is a durable system of laws, institutions, norms, and community commitment that delivers four universal principles: accountability, just law, open government, and accessible and impartial justice.

Accountability

The government as well as private actors are accountable under the law.

Just Law

The law is clear, publicized, and stable and is applied evenly. It ensures human rights as well as property, contract, and procedural rights.

Open Government

The processes by which the law is adopted, administered, adjudicated, and enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient.

Accessible and Impartial Justice

Justice is delivered timely by competent, ethical, and independent representatives and neutrals who are accessible, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve.Footnote 19

These various definitions all consider the rule of law in terms of its goals or outcomes, as opposed to means (or inputs), which is important as it allows “rule of law” to be distinguished from “rule by law” and for different types of institutional arrangements to be used to attain them.

In this chapter, we distance ourselves from questions about how legal orders arise, or how various conceptualizations differ, and instead follow a practical approach to operationalize some of these definitions. We use the indicators of the WJP Rule of Law Index as a starting point. Taken together, these indicators capture the idea of the rule of law as a societal equilibrium in which the state and members of society are bound by law,Footnote 20 and in which the state limits the actions of members of society and provides an enabling environment so that the public interest is served, people enjoy their rights and are protected from violence, and all members of society have access to dispute settlement and grievance mechanisms. This approach has three advantages. First, it looks at the rule of law not only as an ideal of societal coexistence but also as an equilibrium arising from the interaction of institutions and beliefs that shape the behavior and collective actions of members of society. This equilibrium varies depending on the sphere of action of the law and, more importantly, the functioning of the legal and institutional frameworks, the relative power of the agents to whom they apply, and the role of social norms and voluntary compliance. In particular, the normative frameworks, which range from the constitution to secondary laws, executive regulations, and public policies, and the way in which the state agencies in charge of interpreting, enforcing, or making use of them function (congresses, judicial system, police, government agencies, etc.) shape agents’ behavior and beliefs and generate different types of incentives and equilibria.Footnote 21 These institutional frameworks reflect the fundamental patterns of social organization and power distribution in society and are shaped by the agents through institutional and political processes. Second, this approach is consistent with the definitions in the literature and envisages the rule of law comprehensively, incorporating classic guidelines on the exercise of power by the state as propounded in Hobbesian and Madisonian thinking.Footnote 22 It is state-centered and focuses on how governments perform – that is, how they exercise authority and how they administer and enforce laws. Thirdly, our approach is tailored to the data, allowing us to empirically assess the status and evolution of various rule-of-law outcomes and to dissect the factors contributing to the backsliding.

III Data

In this chapter, we explore three hypotheses: (1) The rule of law has deteriorated around the world in recent years. (2) This deterioration has manifested itself through a weakening of the limits on state power (i.e., the weakening of institutional checks and balances and a deterioration in civil liberties reflected in escalating authoritarian behaviors and legal, organizational, administrative, or budgetary changes (the first element of our definition)). In contrast, regressions in the rule of law have not been characterized by increased particularism or a deterioration in the functioning of state agencies in charge of interpreting, applying, administering, or enforcing the law (i.e., police, prosecutors, courts, ombudsmen, anticorruption agencies, regulatory bodies, etc.). (3) This backsliding has been brought about, in part, by a deterioration in institutional checks in authoritarian countries and, in part, by the rise, through relatively democratic processes, of leaders with antipluralist and populist tendencies during this period.

Through the lens of these hypotheses, we examine a selection of annual country indicators that measure different dimensions of the rule of law in a large number of countries around the world. Over the last ten years, the World Justice Project has been collecting information from citizens and legal practitioners in the countries surveyed in order to measure adherence to the rule of law in practice and comprehensively. This information, which forms the basis of the WJP Rule of Law Index, is structured around forty-four outcome indicators (or subfactors) and eight dimensions (or factors): constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice. These dimensions incorporate the two elements that characterize various rule-of-law definitions – constraints on executive discretion and an enabling legal environment that provides justice for the people. The scores under the eight factors and forty-four subfactors of the index are drawn from surveys of the general public and legal practitioners, experts, and academics with expertise in civil and commercial law, constitutional law, civil liberties, criminal law labor law and public health in the countries concerned. These data sources capture citizens’ and professionals’ experiences and perceptions of the performance of the state and its agents and the operation of the legal framework in their respective countries or jurisdictions. Therefore, these data capture the situations perceived within countries and do not touch on transnational institutions. The scores in the 2022 edition of the WJP Rule of Law Index were derived from more than 150,000 household surveys and 3,600 legal practitioner and expert surveys in 140 countries and jurisdictions.

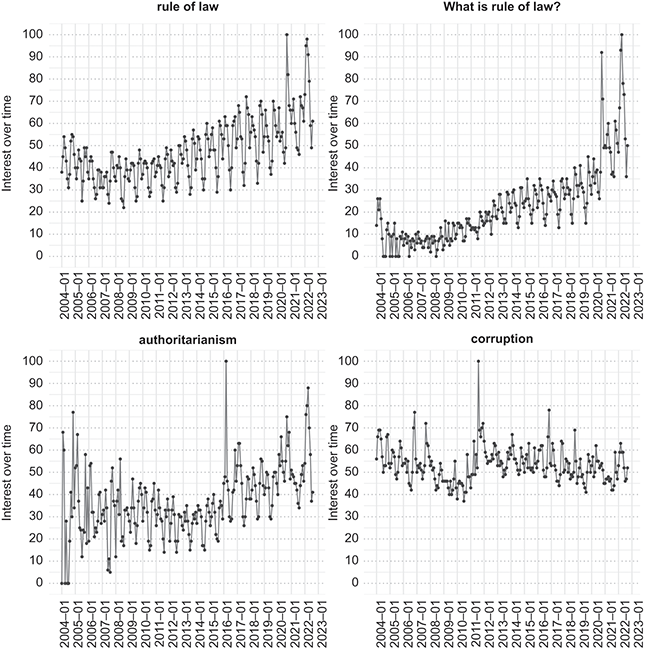

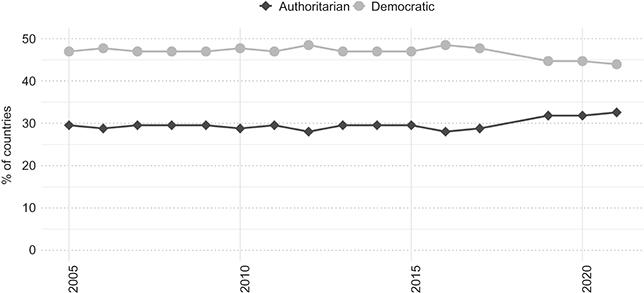

In our analysis, we use aggregate index scores, the scores of the index’s eight factors, and composite indicators constructed from combinations of the index factors and subfactors. The indicators use a scale of 0 to 1, where 1 signifies higher adherence to the rule of law. The data in our sample covers 102 countries and the following years:2015, 2016, 2017–18, 2019, 2020, 2020, 2021, 2022. This selection of years is for two reasons: First, it was in 2015 that the concept of rule of law began to have greater visibility. Figure 3.1 shows the relative importance in Google of various terms related to rule of law and authoritarianism, as well as some controls (such as corruption). In these graphs, the positive trend in recent years starts in 2015. These patterns are confirmed in longitudinal cross-country data sources measuring various governance aspects over a longer time frame, such as V-Dem (see Figure 3.2). The second reason is practical: the WJP data is not comparable to data published before 2015 due to the addition of new countries, changes in the methodologies of normalization, and the addition of concepts and questions from that year onwards. Our final data comprises 714 country–year observations (102 countries and 7 years of data).

Figure 3.1 Google trends of selected terms over time.

Figure 3.2 Percentage of democratic vs. authoritarian regimes (2005–21).

The main advantage of the WJP data is that it is multidimensional, which allows us to explore variations across the different dimensions of the rule of law and not just variations in aggregate scores. The underlying data captures information not only on respect of the law by state agents (or on the functioning of institutional checks and balances) but also on the state’s effectiveness in ensuring that citizens respect the law, enjoy their rights, and obtain access to justice. The data can be reorganized to form new indicators that approximate concepts used in different definitions, including those proposed by Shaffer and Sandholtz.Footnote 23 A further advantage is the data’s numerical nature, which allows us to calculate changes in the different indicators in percentage instead of ordinal terms, and to construct scores from a large number of variables that cover multiple facets of the concepts evaluated. The main disadvantage is that the time frame is relatively short. Nevertheless, the data covers the period of interest. Additionally, the data is based on perceptions and may not reflect the true underlying situation. However, perceptions are important to legal orders as they shape the behavior and beliefs of actors.Footnote 24 To test our third hypothesis, we supplement the WJP data with the V-Party dataset. The latter allows us to construct variables on countries’ exposure to authoritarian regimes over the years. Specifically, we use the V-Party dataset to construct two variables on the political party platforms of candidates coming to power (i.e., antipluralism and populism).

In the analysis, we focus on the percentage changes in the various indicators of the dataset between 2015 and 2022. We use four sets of indicators. The first two are from the WJP: its aggregate rule-of-law indicator, which is an unweighted average of the eight factors that make up the WJP index, and the eight factors of its index. Third, we indicators to approximate the sources of arbitrariness described by Shaffer and Sandholtz. We construct these indicators using the factors and subfactors of the WJP index; however, the matching between the concepts behind the sources of arbitrariness and the data is not very close, as the index indicators come from a different conceptual framework. Fourth, we approximate the indicator of application of law to rulers to the indicator of constraints on government powers of the WJP index (factor 1). This indicator measures the functioning of checks and balances, including legislative constraints, judicial constraints, auditing and review, sanctions, nongovernmental checks, and legally compliant power transitions.

The indicator of predictability of published rules is equivalent to the open government indicator (factor 3). This indicator measures the openness of government defined as “the extent to which a government shares information, empowers people with tools to hold the government accountable, and fosters citizen participation in public policy deliberations.”Footnote 25 The indicator of fora for challenges is equivalent to the civil justice indicator (factor 7), which measures “whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice system,”Footnote 26 and the indicator of proportionate link of means to end and reason-giving is the average of the indicators of judicial constraints (subfactor 1.2) and the absence of improper government influence in civil and criminal justice (subfactors 7.4 and 8.6, respectively). Finally, we also use indicators to capture the concept of control of authoritarianism (or anti-authoritarianism), control of particularism (or anti-particularism), and state capacity. We constructed the anti-authoritarianism indicator using the average of the scores of the indicators of constraints on government powers (factor 1), fundamental rights (factor 4), open government (factor 3) and absence of improper government influence in civil and criminal justice (average of sub-factor 7.4 and 8.6). The anti-particularism indicator is equal to the absence of corruption indicator (factor 2), while the state capacity indicator is the average of the indicators of absence of crime (subfactor 5.1), regulatory enforcement (factor 6), and civil justice and criminal justice (factors 7 and 8). We focus on changes over the last seven years because in most countries changes in the rule of law from one year to the next remain relatively small. In part of our analysis we nonetheless show changes over different time periods in order to encompass variations in indicators when a new administration takes over. Table 3.1 describes the factors used as measures in the WJP Rule of Law Index.

| Factor | Concepts measured |

|---|---|

| 1. Constraints on government powers | Factor 1 measures the extent to which those who govern are bound by law. It covers the means, both constitutional and institutional, by which the powers of the government and its officials and agents are limited and held accountable under the law. It also includes nongovernmental checks on the government’s power, such as a free and independent press. This indicator addresses the effectiveness of the institutional checks on government power by the legislature (1.1), the judiciary (1.2), and independent auditing and review agencies (1.3), as well as the effectiveness of nongovernmental oversight by the media and civil society (1.5), which play an important role in monitoring government actions and holding officials accountable. The extent to which transitions of power occur in accordance with the law is also examined (1.6). In addition to these checks, this factor also measures the extent to which government officials are held accountable for official misconduct (1.4). |

| 2. Absence of corruption | Factor 2 measures the absence of corruption in a number of government agencies. The factor considers three forms of corruption: bribery, improper influence by public or private interests, and misappropriation of public funds or other resources. These three forms of corruption are examined with respect to government officers in the executive branch (2.1), the judiciary (2.2), the military and police (2.3), and the legislature (2.4), and encompass a wide range of possible situations in which corruption – from petty bribery to major kinds of fraud – can occur. |

| 3. Open government | Factor 3 measures open government defined as a government that shares information, empowers people with tools to hold the government accountable, and fosters citizen participation in public policy deliberations. The factor measures whether basic laws and information on legal rights are publicized and evaluates the quality of information published by the government (3.1). It also measures whether requests for information held by a government agency are properly granted (3.2). Finally, it assesses the effectiveness of civic participation mechanisms – including the protection of freedoms of opinion and expression, assembly and association, and the right to petition (3.3), and whether people can bring specific complaints to the government (3.4). |

| 4. Fundamental rights | Factor 4 measures the protection of fundamental human rights. It encompasses adherence to the following fundamental rights: effective enforcement of laws that ensure equal protection (4.1), the right to life and security of the person (4.2), due process of law and the rights of the accused (4.3), freedom of opinion and expression (4.4), freedom of belief and religion (4.5), the right to privacy (4.6), freedom of assembly and association (4.7), and fundamental labor rights, including the right to collective bargaining, the prohibition of forced and child labor, and the elimination of discrimination (4.8). |

| 5. Order and Security | Factor 5 measures how well a society ensures the security of persons and property. Security is a defining aspect of any rule of law society and a fundamental function of the state. It is also a precondition for the realization of the rights and freedoms that the rule of law seeks to advance. This factor encompasses the effectiveness in controlling crime (5.1), the limitation of civil conflict (5.2), and the prevention of resorting to violence to redress personal grievances (5.3). |

| 6. Regulatory enforcement | Factor 6 measures the extent to which regulations are fairly and effectively implemented and enforced. Regulations, both legal and administrative, structure behaviors within and outside of the government. Strong rule of law requires that these regulations and administrative provisions are enforced effectively (6.1) and are applied and enforced without improper influence by public officials or private interests (6.2). Additionally, strong rule of law requires that administrative proceedings are conducted timely, without unreasonable delays (6.4), that due process is respected in administrative proceedings (6.3), and that there is no expropriation of private property without adequate compensation (6.5). |

| 7. Civil justice | Factor 7 measures whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice system. The delivery of effective civil justice requires that the system be accessible and affordable (7.1), free of discrimination (7.2), free of corruption (7.3), and without improper influence by public officials (7.4). The delivery of effective civil justice also presupposes that court proceedings are conducted in a timely manner and are not subject to unreasonable delays (7.5). Finally, recognizing the value of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, this factor also measures the accessibility, impartiality, and efficiency of mediation and arbitration systems that enable parties to resolve civil disputes (7.7). |

| 8. Criminal justice | Factor 8 evaluates the criminal justice system. An effective criminal justice system is a key aspect of the rule of law, as it constitutes the conventional mechanism for redressing grievances and bringing action against individuals for offenses against society. Effective criminal justice systems are capable of investigating and adjudicating criminal offenses successfully and in a timely manner (8.1 and 8.2), through a system that is impartial and nondiscriminatory (8.4), as well as free of corruption and improper government influence (8.5 and 8.6), all while ensuring that the rights of both victims and the accused are effectively protected (8.7). The delivery of effective criminal justice also needs correctional systems that effectively reduce criminal behavior (8.3). Accordingly, an assessment of the delivery of criminal justice should take into consideration the entire system, including the police, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, and prison officers. |

IV Empirical Analysis

1 Is the Rule of Law in Decline?

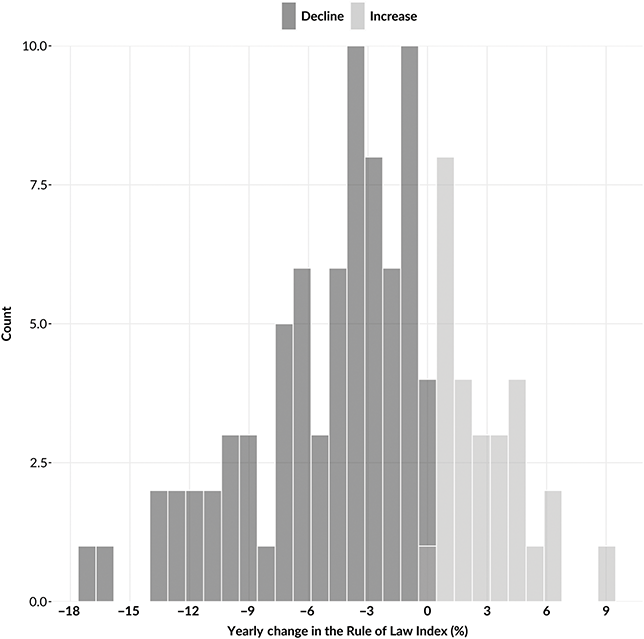

We first explore the hypothesis that the rule of law has been in decline around the world since 2015 and identify the types of countries in which it has regressed. Table 3.2 shows the percentage changes in the rule-of-law scores for the 102 countries analyzed between 2015 and 2022. Three facts stand out. First, the aggregate rule-of-law score has dropped over time. The average percentage change revealed by this indicator during the period of analysis was −3.1 percent. Approximately 74 percent of countries experienced a decline during these years, in some cases of significant magnitude, and only a few experienced improvements. Those that experienced a decline represent 69 percent of the world’s population. Figure 3.3 presents these changes in the form of a histogram. Moreover, the decline has affected all regions of the world, but particularly the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America, and East Asia and the Pacific.

Table 3.2 Annual percentage changes in rule-of-law scores

| Backsliding | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Δ15–16 | Δ16–17 | Δ17–19 | Δ19–20 | Δ20–21 | Δ21–22 | Δ15–22 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | −16.7% | −1.0% | −1.1% | 0.1% | −2.8% | −3.7% | −23.5% |

| Cambodia | −12.2% | −1.1% | 0.5% | 0.7% | −2.3% | −2.3% | −16.1% |

| Venezuela, RB | −13.7% | 4.0% | −3.5% | −2.6% | −1.5% | 3.0% | −14.4% |

| Nicaragua | −1.1% | 3.2% | −6.9% | −2.6% | −3.7% | −3.0% | −13.6% |

| Myanmar | 4.0% | −3.2% | −0.5% | 0.0% | −6.3% | −6.6% | −12.3% |

| Belarus | 1.4% | −4.6% | 0.8% | −0.5% | −7.5% | −2.2% | −12.2% |

| Bolivia | −2.7% | −5.2% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.9% | −5.0% | −11.4% |

| Philippines | −3.6% | −7.7% | 0.4% | 0.8% | −2.9% | 1.7% | −11.0% |

| El Salvador | −3.2% | −2.8% | −0.4% | 3.2% | −3.3% | −4.1% | −10.3% |

| Poland | −0.2% | −5.8% | −0.9% | −1.1% | −2.4% | 0.2% | −9.9% |

| Turkey | −7.2% | −3.1% | 2.7% | 0.3% | −2.5% | −0.3% | −9.9% |

| Mexico | −1.7% | −0.7% | −0.2% | −2.8% | −2.9% | −1.8% | −9.8% |

| Cameroon | −8.0% | −0.1% | 2.8% | −4.4% | −2.1% | 2.1% | −9.7% |

| Hungary | −1.3% | −3.9% | −2.2% | −1.1% | −1.4% | 0.8% | −8.8% |

| Georgia | −0.2% | −6.7% | −0.2% | −1.1% | 0.5% | −0.9% | −8.3% |

| Ghana | −3.7% | 2.4% | −2.5% | −1.9% | −2.2% | −0.5% | −8.2% |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | −1.7% | −4.9% | −0.2% | −1.4% | −0.8% | 0.9% | −8.0% |

| Brazil | 2.9% | −3.1% | −1.2% | −2.9% | −2.9% | −0.5% | −7.6% |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 7.5% | 1.8% | −6.2% | −4.2% | −2.3% | −3.1% | −6.9% |

| Cote d’Ivoire | −1.4% | 1.4% | −1.3% | −0.4% | −3.4% | −1.2% | −6.1% |

| Albania | −3.2% | 0.8% | −0.3% | −1.2% | −1.7% | −0.6% | −6.1% |

| Bangladesh | −2.1% | 0.2% | 1.4% | −1.6% | −2.8% | −0.1% | −4.9% |

| China | 0.3% | 3.8% | −2.7% | −1.5% | −1.9% | −0.8% | −2.9% |

| Tanzania | −1.4% | 0.2% | −0.3% | 0.5% | −1.1% | −0.1% | −2.1% |

| Average | −2.9% | −1.5% | −0.9% | −1.1% | −2.5% | −1.2% | −9.7% |

| Neutral | |||||||

| Country | Δ15–16 | Δ16–17 | Δ17–19 | Δ19–20 | Δ20–21 | Δ21–22 | Δ15–22 |

| Korea, Republic of | −7.7% | −1.0% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 0.4% | −0.4% | −7.0% |

| Botswana | −9.9% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.7% | −1.5% | 0.7% | −6.9% |

| Morocco | 1.4% | −3.4% | −1.2% | −0.5% | −2.6% | −0.2% | −6.4% |

| Zambia | 0.5% | −0.8% | −1.2% | −2.6% | −2.3% | 0.0% | −6.4% |

| Honduras | −0.5% | −3.9% | −0.3% | 0.2% | −2.2% | 0.2% | −6.3% |

| Tunisia | −4.6% | 0.3% | −0.2% | 0.7% | −1.5% | −0.8% | −6.0% |

| Lebanon | −5.4% | 2.7% | 0.2% | −3.3% | −0.9% | 1.0% | −5.8% |

| Uganda | −4.1% | 2.6% | 0.6% | −1.8% | −0.9% | −0.7% | −4.3% |

| Russian Federation | −4.1% | 3.2% | 1.0% | −1.4% | −0.7% | −2.0% | −4.1% |

| Hong Kong SAR, China | 1.3% | −0.4% | −0.2% | −0.4% | −2.0% | −2.3% | −4.1% |

| Singapore | 1.0% | −2.6% | 0.0% | −0.9% | −1.0% | −0.6% | −4.0% |

| Colombia | 1.2% | −0.4% | −1.4% | 0.8% | −2.2% | −2.0% | −4.0% |

| North Macedonia | −1.7% | −2.3% | 1.8% | −0.9% | −0.3% | −0.2% | −3.6% |

| Thailand | −0.3% | −1.8% | −0.4% | 0.9% | −2.2% | 0.1% | −3.6% |

| United States | 1.4% | −1.1% | −1.5% | −0.6% | −2.9% | 1.2% | −3.6% |

| United Arab Emirates | −2.1% | −1.5% | −0.7% | 0.6% | −0.9% | 1.2% | −3.6% |

| Liberia | 0.1% | 1.2% | 1.4% | −1.3% | −2.6% | −2.0% | −3.3% |

| Panama | −1.9% | −0.3% | −0.2% | 0.5% | −0.7% | −0.7% | −3.2% |

| Jordan | 4.1% | 1.5% | −4.8% | −0.1% | −3.0% | −0.6% | −3.2% |

| Madagascar | 0.6% | −3.9% | −1.4% | 2.4% | −0.6% | −0.1% | −3.2% |

| Peru | 3.1% | 1.7% | −2.9% | −1.5% | −2.0% | −0.8% | −2.6% |

| Vietnam | 2.9% | −2.1% | −2.4% | 0.6% | −0.6% | −0.7% | −2.3% |

| Austria | 1.3% | −2.4% | 1.0% | −0.6% | −0.6% | −1.0% | −2.3% |

| Chile | 0.8% | −2.4% | 1.5% | −0.9% | −0.8% | −0.2% | −2.0% |

| Portugal | 1.7% | 0.9% | −0.8% | −1.1% | −0.6% | −2.0% | −1.9% |

| Australia | 0.5% | 0.2% | −0.4% | −0.3% | −1.2% | 0.1% | −1.2% |

| India | 1.4% | 0.9% | −1.2% | −0.5% | −1.9% | 0.3% | −1.0% |

| France | −2.9% | 2.8% | 0.0% | −1.3% | −0.9% | 1.6% | −0.8% |

| New Zealand | 0.0% | −0.3% | −0.5% | 0.3% | 0.7% | −0.6% | −0.4% |

| Costa Rica | 0.4% | −0.1% | 0.3% | −0.5% | −0.8% | 0.4% | −0.2% |

| Japan | −0.8% | 1.1% | −0.8% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| United Kingdom | 3.0% | −0.1% | −0.7% | −1.7% | −0.4% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| Netherlands | 3.4% | −0.7% | −1.5% | −0.5% | −0.5% | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| South Africa | 1.7% | 0.3% | −1.6% | 1.4% | −0.4% | −1.0% | 0.4% |

| Guatemala | −0.1% | 0.1% | 4.6% | −2.3% | −1.2% | −0.6% | 0.4% |

| Sri Lanka | 0.6% | 2.8% | −0.9% | −0.2% | −3.0% | 1.2% | 0.4% |

| Uruguay | 1.9% | −1.9% | −0.6% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| Sweden | 1.3% | 0.2% | −0.4% | 0.2% | 0.0% | −0.5% | 0.8% |

| Dominican Republic | −3.4% | −0.4% | −0.4% | 3.1% | 0.0% | 2.1% | 0.9% |

| Pakistan | 1.1% | 1.9% | −0.2% | −0.7% | −0.4% | −0.6% | 1.0% |

| Belize | −2.8% | −0.2% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 3.6% | 1.3% |

| Nigeria | 9.0% | −1.2% | −1.0% | −0.9% | −3.7% | −0.2% | 1.5% |

| Croatia | 1.0% | 1.0% | −0.6% | 1.1% | −1.0% | 0.7% | 2.3% |

| Norway | 1.7% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.1% | 0.5% | −1.5% | 2.3% |

| Romania | 6.6% | −0.7% | −1.9% | −1.5% | −0.8% | 0.9% | 2.4% |

| Canada | 3.8% | 0.3% | −0.1% | −0.2% | −1.0% | 0.1% | 2.9% |

| Slovenia | 1.9% | −0.3% | 0.5% | 1.7% | −0.4% | −0.4% | 3.0% |

| Average | 0.2% | −0.2% | −0.3% | −0.2% | −1.1% | −0.1% | −1.8% |

| Improving | |||||||

| Country | Δ15-16 | Δ16-17 | Δ17-19 | Δ19-20 | Δ20-21 | Δ21-22 | Δ15-22 |

| Ethiopia | −9.4% | −0.8% | 3.3% | 5.6% | −1.0% | −2.7% | −5.6% |

| Serbia | −0.7% | −0.3% | 0.1% | 0.6% | −1.8% | −0.9% | −3.0% |

| Afghanistan | −2.2% | −0.3% | 0.9% | 4.3% | −2.7% | −2.8% | −2.8% |

| Nepal | −2.2% | 1.1% | 0.8% | −0.7% | −1.1% | 0.5% | −1.7% |

| Kyrgyz Republic | −0.7% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.4% | −3.7% | −0.2% | −1.7% |

| Malaysia | −5.2% | −0.5% | 3.6% | 5.1% | −1.4% | −2.4% | −1.1% |

| Bulgaria | −0.8% | −2.4% | 2.4% | 0.5% | −1.0% | 0.8% | −0.6% |

| Senegal | 0.8% | −4.0% | 0.3% | −0.1% | 0.5% | 2.7% | 0.2% |

| Mongolia | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.3% | −2.2% | 2.0% | −1.7% | 0.3% |

| Ecuador | −3.4% | 3.7% | 1.2% | 2.0% | −0.1% | −2.5% | 0.7% |

| Kenya | −3.5% | 4.0% | 0.5% | −0.2% | −0.9% | 1.0% | 0.7% |

| Indonesia | −0.1% | −0.9% | 0.9% | 1.3% | −1.0% | 1.2% | 1.3% |

| Czech Republic | 4.1% | −1.2% | −1.4% | 0.6% | −0.4% | 0.5% | 2.1% |

| Germany | 2.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.4% | −1.0% | 2.3% |

| Finland | 3.0% | −0.3% | 0.6% | −0.1% | 0.4% | −0.9% | 2.6% |

| Sierra Leone | 0.1% | −0.9% | −1.5% | 1.3% | 2.8% | ||

| Jamaica | 1.5% | 0.7% | −2.0% | 0.8% | 0.4% | 1.4% | 2.8% |

| Greece | −0.2% | 0.5% | 2.3% | −0.9% | −0.5% | 1.9% | 3.1% |

| Belgium | 2.8% | −2.0% | 2.4% | −0.5% | 0.6% | −0.1% | 3.1% |

| Denmark | 1.9% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 3.6% |

| Malawi | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 0.2% | 4.0% |

| Italy | 0.1% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 1.6% | 4.1% |

| Ukraine | 1.9% | 1.6% | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.6% | −1.3% | 4.7% |

| Kazakhstan | 1.3% | 2.2% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.3% | −0.9% | 4.9% |

| Argentina | 6.7% | 5.0% | 0.1% | −0.5% | −3.7% | −1.9% | 5.4% |

| Burkina Faso | 3.1% | 4.8% | 0.5% | −0.1% | −0.9% | −1.4% | 6.1% |

| Estonia | 1.8% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 0.0% | −0.1% | 1.7% | 6.2% |

| Spain | 2.0% | 0.9% | 2.4% | 1.3% | 0.1% | −0.2% | 6.6% |

| Zimbabwe | 0.8% | 0.6% | 7.1% | −1.5% | 0.0% | 0.7% | 7.7% |

| Moldova | 2.4% | −0.5% | −1.0% | 2.2% | 3.2% | 1.9% | 8.6% |

| Uzbekistan | −1.4% | 1.9% | 1.0% | 1.7% | 4.1% | 1.4% | 8.9% |

| Average | 0.3% | 0.6% | 1.1% | 0.7% | −0.3% | 0.0% | 2.5% |

Figure 3.3 Distribution of year-to-year changes in rule-of-law scores (2015 to 2022).

Second, rule-of-law backsliding has been more pronounced in countries that were already authoritarian and where the rule of law was already weak (i.e., Belarus, Cambodia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela) or in countries that have been exposed to emerging leaders with authoritarian tendencies (i.e., Brazil, El Salvador, Hungary, Poland, Philippines, Turkey). The average rule-of-law score for the ten countries in which the decline was steepest is 0.48, while the score for the remaining countries with negative changes is 0.58. In contrast, countries that experienced moderate declines between 0 and −5 percent during the study period (42 percent of the countries) are found across the entire rule-of-law spectrum. Countries that experienced improvements during these years comprise those that underwent ambitious reform processes (i.e., Kazakhstan, Moldova, and Uzbekistan), regime changes (Zimbabwe), changes of administration with ups and downs (i.e., Argentina and Burkina Faso), or minor improvements over the years (countries in the European Union). Finally, with the exception of countries that have experienced significant deterioration, in most countries the rule of law has waxed and waned over the years. In some cases, the rule of law strengthened at the beginning of the period and has weakened in recent years (i.e., Nigeria, Morocco, and Peru). In others, changes have occurred intermittently throughout the period (i.e., United Kingdom and South Africa). Interestingly, in some cases, year-to-year changes in the rate of changes – particularly when downwards – or changes from positive to negative, or vice versa, appear to be associated with changes in administration (i.e., Philippines in 2016, and the United States in 2016 and 2020). In other cases, however, they reflect small changes in the course of an administration (i.e., France since 2017). The greatest overall deterioration occurred notably during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Next, we explore changes in the index components and other indicators developed from the disaggregated data. Table 3.3 presents the descriptive statistics. In comparison with the overall rule-of-law scores, the scores for institutional checks on executive discretion, particularly factors 1 (constraints on government powers) and 4 (fundamental rights), have shown a much more pronounced deterioration during this period, both in terms of magnitude and number of countries. Factor 1 declines were experienced in 64 percent of countries and factor 4 declines in 76 percent of countries. The average percentage change for these indicators was −4.8 percent and −6.7 percent. The scores of other indicators constructed from the disaggregated data show similar trends. Scores for the sources of arbitrariness fell in more than 60 percent of countries, while those measuring anti-authoritarianism fell in 68 percent of countries (i.e., authoritarianism increased in 68 percent of countries), with the drop averaging −5.5 percent. In contrast, the indicators that measure the functioning of the legal system and, more broadly, the application of the law by state agents – i.e., security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, and criminal justice – fell relatively little. Scores for the state capacity indicator fell in only 56 percent of countries, by an average of −0.3 percent.

Table 3.3 Summary statistics based on the WJP Rule of Law Index

| Scores | Changes over time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average score in 2015 | Average score in 2022 | Δ 2015–22 | Proportion of countries that improved | Proportion of countries that declined | Δ 2019–22 | |

| Rule-of-law score | 0.57 | 0.55 | -2.4% | 40% | 60% | −1.4% |

| F1. Constraints on government powers | 0.58 | 0.55 | -4.8% | 36% | 64% | −2.2% |

| F2. Absence of corruption | 0.52 | 0.51 | -0.9% | 40% | 60% | −1.9% |

| F3. Open government | 0.55 | 0.53 | -2.6% | 48% | 62% | −0.5% |

| F4. Fundamental rights | 0.60 | 0.57 | -6.3% | 24% | 76% | −2.7% |

| F5. Order and security | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.0% | 44% | 66% | −0.3% |

| F6. Regulatory enforcement | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.9% | 60% | 40% | −1.0% |

| F7. Civil justice | 0.55 | 0.54 | -1.1% | 46% | 54% | −1.2% |

| F8. Criminal justice | 0.49 | 0.48 | -1.8% | 44% | 56% | −1.2% |

2 Unpacking the Backsliding: Country Groupings

These findings suggest that the rule of law has indeed weakened worldwide, and this drop appears to have been caused by a weakening of limitations on the exercise of state power and a deterioration in fundamental rights (including the closure of civic space). In this section, we explore this hypothesis and unpack the backsliding of the rule of law. Given the slight variation in the aggregate scores, our analysis is based on variations over time in the different dimensions (or factors) of the WJP Rule of Law Index. We use cluster analysis to group countries according to how far each country lies from the others in terms of the overall change in factor scores between 2015 and 2022. To use the maximum possible variations, our main analysis focuses on the percentage change in the factor scores of the index. Later, we perform a similar analysis using the percentage change in the scores of the other two sets of indicators to classify countries. This numerical method allows us to organize the information efficiently and assign labels that provide a concise description of patterns of similarities and differences in rule-of law-trends. Once the information is organized, we can explore (a) the variations in the rule of law over time for the different countries, (b) the characteristics of the countries that have experienced declines, (c) the variations in the components of the index that explain the movements in the rule of law for different countries, and (d) factors that could be associated with the declines and, more broadly, with variations in the rule of law over time. Since the number of groups to classify is unknown, we use hierarchical clustering techniques.Footnote 27

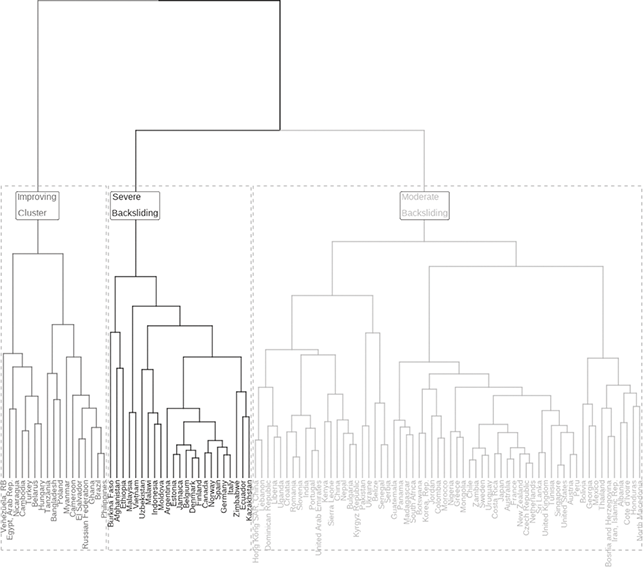

In our analysis, we identify three clusters. The dendrogram in Figure 3.4 shows the distribution of countries in each of these clusters. The first cluster comprises seventeen countries, the second sixty-two countries, and the third twenty-three countries. These groups show clear differences in rule-of-law trends. The panels of Table 3.2 present the cluster in which each country is located: backsliding, neutral, or improving. Although there are some exceptions, the clusters closely resemble the patterns identified in this table showing the aggregate scores. Figure 3.5 shows the changes in the aggregate rule-of-law indicator for the countries in each of the three groups. The countries in the first cluster experienced a drop in the rule-of-law score of −9.7 percent during the period. We label this group the “severe backsliding” cluster. Countries in the second group underwent a decline, but not as severe, with an average change of −3 percent. We call this group the “moderate backsliding” cluster. In contrast, the countries in the third cluster slightly improved their scores during the period, with an average change of 2.5 percent. We call this group the “improving” cluster. The difference between the three groups is statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

Figure 3.4 Distribution of countries by cluster.

Figure 3.5 Percentage changes in rule-of-law scores between 2015 and 2022, by clusters.

Table 3.4 shows additional statistics for the countries in the three clusters. The first section (A) presents the distribution of the clusters by region, the second (B) by income level, and the third (C) by socioeconomic characteristics. The fourth section (D) shows the rule of law scores at the beginning of the period. Three points deserve attention. First, as shown in Table 3.3, backsliding occurred in all regions of the world. Second, severe backsliding occurred mainly in middle-income countries, while moderate backsliding occurred mainly in high- and middle-income countries. Finally, countries in the backsliding cluster had lower scores than the other countries in 2015. Figure 3.6 is a scatter plot showing changes in the WJP Rule of Law Index between 2015 and 2022 and the levels of the rule of law in 2015 for the three groups of countries. Countries in the first group tend to have lower levels of rule of law, with the exception of Poland, while those in the second and third groups are spread across the entire rule-of-law spectrum.

Table 3.4 Country characteristics, by cluster

| Average for all countries | Backsliding | Neutral | Improving | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Distribution across regions | ||||

| EU, EFTA, and North America | 24% | 8% | 26% | 32% |

| East Asia and Pacific | 15% | 17% | 17% | 10% |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 13% | 21% | 4% | 20% |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 19% | 25% | 21% | 10% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 7% | 8% | 11% | 0% |

| South Asia | 6% | 4% | 6% | 6% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 18% | 17% | 15% | 22% |

| B. Distribution across income groups | ||||

| High | 32% | 8% | 47% | 29% |

| Upper-middle | 30% | 42% | 28% | 26% |

| Lower-middle | 29% | 50% | 19% | 29% |

| Low | 8% | 0% | 6% | 16% |

| C. Socioeconomic characteristics | ||||

| Δ% GDP per capita (2015–22) | 1.13% | 0.57% | 2.15% | 1.24% |

| Unemployment rate (2015) | 7.46% | 7.35% | 7.31% | 7.74% |

| Share of world population (2021) | - | 37% | 48% | 15% |

| D.: Rule of law | ||||

| Rule-of-law score in 2015 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

Figure 3.6 Rule-of-law changes and levels, by clusters.

3 Drivers of the Decline

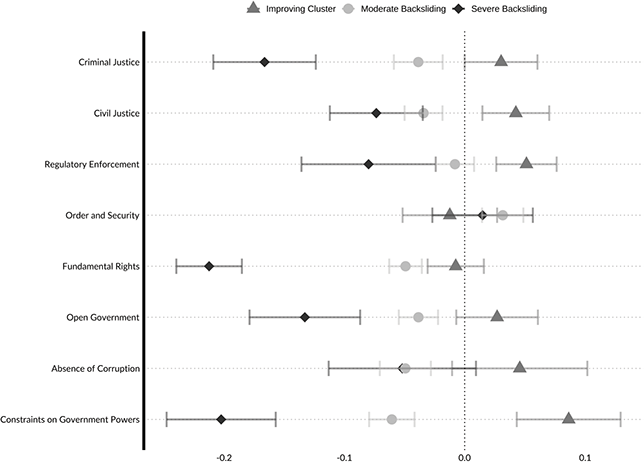

We next examine the main drivers of these rule-of-law patterns. Figure 3.7 shows the average change in the indicators (factors) of the WJP Rule of Law Index over the 2015–22 period for the countries in each of the three clusters. Three findings stand out. First, the indicators in each of the groups tend to move in the same direction. The countries in the severe backsliding cluster show a statistically significant drop in almost all indicators. The indicators in the moderate backsliding group experienced statistically significant declines in almost all indicators, albeit of lesser magnitude, while the indicators in the third group experienced improvements in most indicators. Second, the indicators that fell most in the severe backsliding cluster are those measuring constraints on government powers, fundamental rights, criminal justice, and open government, which fell by 20 percent, 21 percent, 17 percent and 13 percent respectively. The indicators measuring constraints on government powers and fundamental rights also fell in the moderate backsliding group and in some countries in the improving cluster. Figure 3.8, a scatter plot showing the percentage changes in these two indicators, confirms the clear differences that exist in these areas between the three groups of countries. The chart also reveals a clear link between checks and balances and the protection of individual rights. Finally, the indicators measuring corruption, order and security, regulatory enforcement, and civil justice fell much less in the countries in the severe backsliding cluster, declined slightly or remained unchanged in those in the moderate backsliding cluster, and improved in the third cluster countries.

Figure 3.7 Percentage changes in rule-of-law factor scores between 2015 and 2022, by clusters.

Figure 3.8 Percentage changes in scores for constraints on government powers and fundamental rights between 2015 and 2022, by clusters.

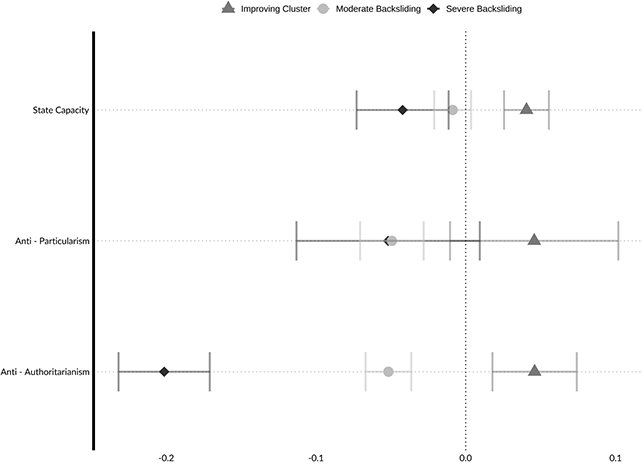

These differences between clusters are robust to different rule-of-law definitions. Figures 3.9 and 3.10 show the changes over time in different rule-of law-indicators for the three groups of countries. Figure 3.9 shows the average change in the indicators proposed by Shaffer and Sandholtz over the 2015–22 period for the countries in each of the three clusters. These indicators focus on the imposition of limits on the exercise of power. Countries in the first group (severe backsliding) suffered declines under all indicators, with more pronounced declines under those measuring application of the law to rulers and proportionate link of means to end and reason-giving. The countries in the second group (moderate backsliding) also worsened under all indicators, although to a lesser extent and in a more homogeneous manner. Finally, the indicators in the third group showed improvements in all areas. Figure 3.10 shows the average changes for the indicators measuring control of authoritarianism (anti-authoritarianism), control of particularism (anti-particularism) and state capacity. The results confirm the above patterns. Countries in the first group suffered significant declines according to the indicators measuring control of authoritarianism, and more moderate declines according to the other two indicators. The countries in the second group (moderate backsliding) suffered similar declines in all areas and of lesser magnitude. Countries in the third group improved in all areas.

Figure 3.9 Percentage changes in the scores under indicators measuring sources of arbitrariness between 2015 and 2022, by clusters.

Figure 3.10 Percentage changes in the anti-authoritarianism, anti-particularism and state capacity scores between 2015 and 2022, by clusters.

To explore the type of countries found in each of the groups, Figure 3.11 shows the percentage changes in different indicators over the study period and their levels in 2015. Consistent with the results in Table 3.2, rule-of-law backsliding has been more pronounced in authoritarian countries that began with weak rule of law. Countries with a less severe decline in the rule of law constitute a mixed group, some of them having strong institutions and higher levels of rule of law (France, Korea, Portugal), and others weak institutions and low levels of rule of law (India). Countries that have improved are either countries in transition, with weak rule of law, or countries with strong rule of law producing marginal changes. Although there is no single pattern, these results support the idea that the level of deterioration in the rule of law depends on the strength of institutions. Leaders of states with weak institutions have fewer constraints and can accelerate autocratization. In contrast, leaders of states with stronger institutions face greater constraints and checks, which serve as a buffer against backsliding. The source of these checks can be varied, and may include stronger legal and institutional frameworks, a developed bureaucracy, an effective opposition, a critical and free civil society and press, or free elections and democratic processes that allow for change of government.

Figure 3.11 Percentage changes (2015–22) and levels in 2015 for the indicators measuring constraints on government powers and fundamental rights, by clusters.

The clustering of countries may vary due to year-to-year variations in the different indicators or to different ways of organizing the rule-of-law data. To check the robustness of our results, we performed two exercises. First, we repeated the cluster analysis by changing the starting periods. We found that 47 percent of the countries in the 2015–22 severe backsliding cluster remained in this group in three of the five exercises conducted for the different study periods. This figure rose to 65 percent when we considered the countries in the severe and moderate backsliding groups. In contrast, many countries in the improving group moved after changing the initial periods.

These results make sense. The countries in the severe backsliding group have experienced a significant and steady deterioration in the rule of law, measured through declines in all or almost all of the index indicators/factors. In contrast, countries in the other groups have suffered less severe downturns, or even experienced improvements, but these have been of lesser intensity, shorter, and linked to changes in administrations throughout the study period. At the same time, these countries have made little progress in improving regulatory enforcement, fighting corruption, or advancing justice, their scores for the other index factors having changed (positively or negatively) to a lesser extent depending on the period of analysis. Second, we performed cluster analyses for the two groups of indicators explored above. In both cases, the classification yields three groups, one with severe declines and two other groups that are quite similar and less susceptible to change over the time period, in part because these exercises rely on fewer indicators. In spite of this, 82 percent of the countries in our original severe backsliding cluster fall into the clusters grouping countries with largest deteriorations resulting from the exercises involving the other two sets of indicators. In addition, we performed a cluster analysis on changes in index factors between 2015 and 2022 and the respective levels of these indicators in 2015. This analysis yielded a different classification comprising three groups: one similar to the severe backsliding cluster, another consisting of countries with high levels of rule of law, and a residual group containing the remaining countries.

Taken together, these results confirm the initial data trends. Of the countries in which the rule-of-law scores fell, 87 percent experienced a decline in the scores for constraints on government powers and 85 percent a decline in the scores for fundamental rights. In 79 percent of countries, both indicators fell. Similarly, 90 percent of countries in which the rules of law fell experienced a decline in the scores for freedom of opinion and expression or freedom of association, which are a proxy for civic space. These results lend support to our hypothesis that the deterioration in the rule of law is the result of a weakening of limitations on state power and a deterioration in fundamental rights, not the result of an increase in the level of particularism (or a rise in corruption) or a deterioration in the functioning of the legal system (i.e., law enforcement agencies, regulatory agencies, or judicial actors).

We now turn from manifestations of the decline trends in the rule of law to focus on political factors that could explain these trends. As we saw in Table 3.2, in many countries the rule of law moves in cycles – that is, an abrupt trend change between two years led to a situation that lasted several years until another abrupt trend change occurred. The length and extent of these cycles vary from country to country, which suggests that rule-of-law changes may be linked to changes in political leadership, and thus in the structure of government. Recent literature has shown that populism and antipluralistic trends are dangerous for the rule of law. According to the literature, populist and antipluralistic leaders rise to power because of the failure of governments, elites, and institutions to meet citizens’ growing demands. Such leaders use narratives centered on people and antigroups, often the political elite (antiestablishment). These narratives change little when the leaders come to power; on the contrary, they expand to include democratic institutions, media, and civil society. Bugaric and Kuhelj assert that the surge of populism and authoritarian populism in countries whose core principles no longer enjoy democratic support put the rule of law and liberal institutions in danger, largely because populist leaders have the legitimacy to change laws and even constitutions – as in Hungary – that protect minorities, limit discretion, and give voice to different political groups.Footnote 28 Sato and Arce argue that populist and antipluralistic leaders could be associated with democratic backsliding.Footnote 29 They found that the exclusionary rhetoric of populist leaders in some countries in Latin America and their attack on existing democratic norms have been used as a tool to win elections. In other cases, backsliding occurs through participatory processes, such as referendums or assemblies.Footnote 30

We examine this hypothesis using the V-Party dataset to construct a measure of exposure to authoritarian platforms. More specifically, we use two composite annual indicators based on the platforms and speeches of the political parties that have come to power in each country between 2015 and 2019:Footnote 31 (a) an antipluralism index that measures the extent to which representatives of a given party show a lack of commitment to democratic norms prior to elections; and (b) a populism index that measures the extent to which representatives of a given party use a populist rhetoric. The first indicator is an aggregate score that a group of experts assign to a political party based on the treatment of political opponents and minority groups by its leaders or the respect they show for free and fair elections or political freedoms, among other aspects. The second indicator is an aggregate score that a group of experts assign to a political party based on the use of antielite rhetoric or the frequency with which they glorify ordinary people and identify with them, among other aspects. We use these indices to define two binary variables that equal one if the head of government resulting from the election belongs to a political party whose antipluralism or populist index is above the seventieth percentile of the value for all parties recorded between 2015 and 2019. We say that a country experienced a change of party administration to an antidemocratic platform if at least one of these two variables is equal to one. Conversely, we say that a country experienced a change of party administration to a democratic platform if both these variables are equal to zero.

Table 3.5 shows the change in the rule of law between 2015 and 2022 for each of the countries in the three clusters, together with categorical variables indicating whether, during the 2015–19 period, there was a regime change in which the winning party used an antipluralist or populist (antidemocratic) platform, whether there was a regime change in which the winning party did not use either of these platforms (democratic), whether there was no platform change (although there may have been a change of party), or whether there were both democratic and antidemocratic changes in the country during the period of analysis. Although the data does not indicate whether the parties that came to power in 2019 were still in power in 2022 or whether there was a platform change after 2019, it reveals some interesting patterns. First, the vast majority of countries did not experience regime changes with different political platforms, which may simply reflect the shortness of the time frame. Despite this, the rule of law fell in many of them. Second, most of the countries listed as backsliding did not experience a regime change. This makes sense since many of those countries are autocracies, which supports the idea that a weakening of the rule of law, checks and balances, and accountability mechanisms tends to lead to a weakening of democratic processes. Nevertheless, several countries, including Poland, Turkey, Mexico, Brazil, Iran, and Côte d’Ivoire, did experience power changes and new leaders rising to power on antipluralist or populist platforms. On average, the rule of law in countries with no regime change and those with regime changes to antidemocratic platforms deteriorated by approximately the same amount within the backsliding cluster. Third, in general, the rule of law improved (or deteriorated less) in countries where leaders came to power on pluralist and nonpopulist (what we call democratic) platforms, compared to countries where the leaders used antipluralist or populist platforms.

Table 3.5 Rule-of-law backsliding and regime change

| Backsliding | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | Δ2015–22 | Regime change |

| Egypt | −23.5% | No change |

| Cambodia | −16.1% | No change |

| Venezuela | −14.4% | No change |

| Nicaragua | −13.6% | No change |

| Myanmar | −12.3% | Democratic to antidemocratic |

| Belarus | −12.2% | No change |

| Bolivia | −11.4% | No change |

| Philippines | −11.0% | No change |

| El Salvador | −10.3% | No change |

| Poland | −9.9% | Change to antidemocratic |

| Turkey | −9.9% | Antidemocratic |

| Mexico | −9.8% | Antidemocratic |

| Cameroon | −9.7% | No change |

| Hungary | −8.8% | No change |

| Georgia | −8.3% | No change |

| Ghana | −8.2% | No change |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | −8.0% | Democratic/antidemocratic |

| Brazil | −7.6% | Antidemocratic |

| Iran | −6.9% | Antidemocratic |

| Côte d’Ivoire | −6.1% | Antidemocratic |

| Albania | −6.1% | No change |

| Bangladesh | −4.9% | No change |

| China | −2.9% | No change |

| Tanzania | −2.1% | No change |

| No change | −10.2% | 16 |

| Antidemocratic | −8.4% | 6 |

| Democratic | - | 0 |

| Democratic to antidemocratic | −10.2% | 2 |

| Neutral | ||

| Country | Δ2015–22 | Regime change |

| Korea, Republic of | −7.0% | Democratic |

| Botswana | −6.9% | No change |

| Morocco | −6.4% | No change |

| Zambia | −6.4% | No change |

| Honduras | −6.3% | No change |

| Tunisia | −6.0% | No change |

| Lebanon | −5.8% | No change |

| Uganda | −4.3% | No change |

| Russian Federation | −4.1% | No change |

| Hong Kong SAR, China | −4.1% | No change |

| Singapore | −4.0% | No change |

| Colombia | −4.0% | Antidemocratic |

| Thailand | −3.6% | Democratic |

| Thailand | −3.6% | Antidemocratic |

| United States | −3.6% | Antidemocratic |

| United Arab Emirates | −3.6% | No change |

| Liberia | −3.3% | No change |

| Panama | −3.2% | Antidemocratic |

| Jordan | −3.2% | No change |

| Madagascar | −3.2% | No change |

| Peru | −2.6% | Democratic |

| Vietnam | −2.3% | No change |

| Austria | −2.3% | Democratic |

| Chile | −2.0% | Democratic |

| Portugal | −1.9% | Democratic |

| Australia | −1.2% | Democratic |

| India | −1.0% | Antidemocratic |

| France | −0.8% | Democratic |

| New Zealand | −0.4% | Democratic |

| Costa Rica | −0.2% | Antidemocratic |

| Japan | 0.3% | No change |

| United Kingdom | 0.4% | No change |

| Netherlands | 0.4% | No change |

| South Africa | 0.4% | No change |

| Guatemala | 0.4% | Democratic/antidemocratic |

| Sri Lanka | 0.4% | Anti-democratic |

| Uruguay | 0.5% | Democratic |

| Sweden | 0.8% | Democratic |

| Dominican Republic | 0.9% | No change |

| Pakistan | 1.0% | Antidemocratic |

| Belize | 1.3% | No change |

| Nigeria | 1.5% | Antidemocratic |

| Croatia | 2.3% | Democratic |

| Norway | 2.3% | Democratic |

| Romania | 2.4% | No change |

| Canada | 2.9% | Democratic |

| Slovenia | 3.0% | Democratic |

| No change | −2.9% | 22 |

| Antidemocratic | −1.4% | 9 |

| Democratic | −0.7% | 15 |

| Democratic/antidemocratic | 0.4% | 1 |

| Improving | ||

| Country | Δ2015–22 | Regime change |

| Ethiopia | −5.6% | No change |

| Serbia | −3.0% | Anti-democratic |

| Afghanistan | −2.8% | No change |

| Kyrgyz Republic | −1.7% | No change |

| Malaysia | −1.1% | Antidemocratic |

| Senegal | 0.2% | No change |

| Mongolia | 0.3% | Antidemocratic |

| Ecuador | 0.7% | No change |

| Kenya | 0.7% | Democratic/antidemocratic |

| Indonesia | 1.3% | Antidemocratic |

| Czech Republic | 2.1% | Democratic/antidemocratic |

| Germany | 2.3% | No change |

| Finland | 2.6% | Democratic |

| Greece | 3.1% | Democratic |

| Greece | 3.1% | Antidemocratic |

| Belgium | 3.1% | Democratic |

| Denmark | 3.6% | Democratic |

| Malawi | 4.0% | No change |

| Italy | 4.1% | Democratic |

| Ukraine | 4.7% | Antidemocratic |

| Kazakhstan | 4.9% | No change |

| Argentina | 5.4% | Democratic/antidemocratic |

| Burkina Faso | 6.1% | Democratic/antidemocratic |

| Estonia | 6.2% | Democratic |

| Spain | 6.6% | Democratic |

| Zimbabwe | 7.7% | No change |

| Moldova | 8.6% | Antidemocratic |

| Uzbekistan | 8.9% | No change |

| No change | 1.9% | 10 |

| Antidemocratic | 2.0% | 7 |

| Democratic | 4.2% | 7 |

| Democratic To antidemocratic | 3.6% | 4 |

Taken together, these results show that the rule of law has indeed deteriorated in most countries around the world. In some countries, this deterioration has been continuous; in others, it has varied over the years. The deterioration in the rule of law is associated with a weakening of limitations on state power, as measured by governmental and nongovernmental checks and balances and the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms. Except in those cases that have experienced a sharp decline, the weakening of the rule of law is not associated with an acute deterioration in the application or enforcement of the law or diminished access to justice. These indicators, however, have shown little improvement in recent years. The weakening of the rule of law appears to be associated, in part, with an increase in the authoritarian tendencies of already authoritarian regimes and, in part, with the rise of antipluralist and populist leaders. In general, the rule of law has strengthened in most high-income countries (although the United States is a noteworthy exception), which reveals an emerging global divergence between high-rule-of-law countries (liberal democracies) and low-rule-of-law countries (autocracies).

V Conclusion

In this chapter we have presented evidence of the backsliding in the rule of law around the world. This deterioration has been caused by the weakening of institutional checks and balances and the closing of civic space, and has not been homogeneous around the world. This backsliding of the rule of law raises important challenges.

From an academic point of view, there are questions that require immediate attention. For example, what are the mechanisms that have led to rule-of law-backsliding? What factors explain this deterioration over time? What institutional or social safeguards are most effective in preventing this erosion? Is it possible to reverse these trends? How does this type of backsliding impact other rule-of-law outcomes? How does it affect other socioeconomic outcomes? Answering these questions requires detailed cross-country datasets that go beyond perceptions, case studies, and the segmentation of the problems analyzed. More importantly, it calls for the rule of law to be understood as the result of interplay between a multiplicity of institutions and actors, each with differing degrees of power and incentives.

From a practical point of view, the deterioration of the rule of law can have an enormous social impact. The weakening of institutional checks and balances – by restricting the independence and autonomy of democratic institutions and closing civic spaces – reduces government accountability and the incentives of state agents to deliver results or improve their performance, as well as the ability of citizens to exert pressure or seek change through the ballot box. This is particularly worrisome, given other shortcomings in the rule of law that afflict people around the world – i.e., corruption, violence, legal marginalization, and lack of access to justice. Meanwhile, this deterioration continues to expand across the apparatus of government and the legal system, becoming all the harder to reverse.

Combating these tendencies is a complicated political problem, given the lack of incentives for authoritarian leaders and power groups to accept being bound by certain rules and the citizens’ growing disaffection with existing institutions and the establishment that populist and antipluralist leaders have been quick to exploit. That said, the fact that rule-of-law backsliding is often gradual means that it potentially can be reversed if a new administration that is more committed to the rule of law takes office.