Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Marble Camera

- PART I

- 1 The Sculptor's Dream: Living Statues in Early Cinema

- 2 The Mystery … The Blood … The Age of Gold: Sculpture in Surrealist and Surreal Cinema

- 3 Carving Cameras on Thorvaldsen and Rodin: Mid-Twentieth- Century Documentaries on Sculpture

- 4 Anatomy of an Ovidian Cinema: Mysteries of the Wax Museum

- 5 The Night of the Human Body: Statues and Fantasy in Postwar American Cinema

- 6 From Pompeii to Marienbad: Classical Sculptures in Postwar European Modernist Cinema

- 7 Of Swords, Sandals, and Statues: The Myth of the Living Statue

- 8 Coda: Returning the Favor (A Short History of Film Becoming Sculpture)

- PART II

- Bibliography

- About the Authors

- Index

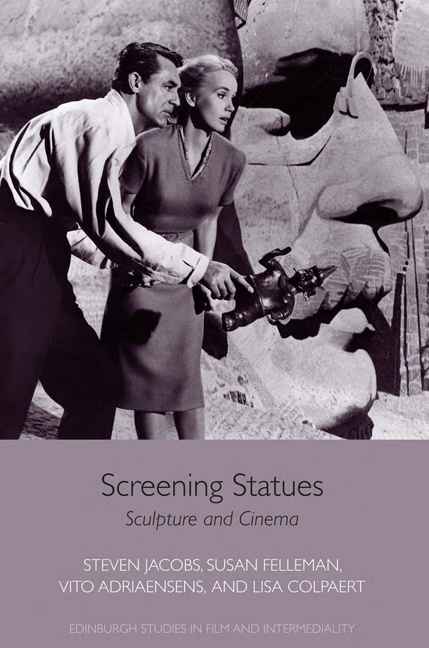

7 - Of Swords, Sandals, and Statues: The Myth of the Living Statue

from PART I

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Marble Camera

- PART I

- 1 The Sculptor's Dream: Living Statues in Early Cinema

- 2 The Mystery … The Blood … The Age of Gold: Sculpture in Surrealist and Surreal Cinema

- 3 Carving Cameras on Thorvaldsen and Rodin: Mid-Twentieth- Century Documentaries on Sculpture

- 4 Anatomy of an Ovidian Cinema: Mysteries of the Wax Museum

- 5 The Night of the Human Body: Statues and Fantasy in Postwar American Cinema

- 6 From Pompeii to Marienbad: Classical Sculptures in Postwar European Modernist Cinema

- 7 Of Swords, Sandals, and Statues: The Myth of the Living Statue

- 8 Coda: Returning the Favor (A Short History of Film Becoming Sculpture)

- PART II

- Bibliography

- About the Authors

- Index

Summary

Vito Adriaensens

As sculpture is the classical art par excellence, statues abound in films set in Greek or Roman antiquity. Moreover, many of the mythological tropes involving sculptures that have persisted on the silver screen have their origins in classical antiquity: the Ovidian account of a Cypriot sculp¬tor named Pygmalion who falls in love with his ivory creation and sees it bestowed with life by Venus, Hephaistos's deadly automatons, the petrifying gaze of the Medusa, and divine sculptural manifestation, or agalmatophany, for instance. This chapter investigates the myths of the living statue as they originated in Greek and Roman literary art histories and found their way to the screen. It will do so by tracing the art-historical form and func¬tion of classical statuary to the cinematic representation of living statues in a broad conception of antiquity. The cinematic genre in which mythic sculptures thrive is that of the sword-and-sandal or peplum film, where a Greco-Roman or ersatz classical context provides the perfect backdrop for spectacular special effects, muscular heroes, and fantastic mythologi¬cal creatures. The 1960s and 1970s proved a fruitful breeding ground, with stop-motion wizard Ray Harryhausen contributing heavily to the success¬ful animation of mythical statues in Jason and the Argonauts (Don Chaffey, 1963), The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (Gordon Hessler, 1973), Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (Sam Wanamaker, 1977), and Clash of the Titans (Desmond Davis, 1981); and after a second wave in the 1980s with sword-and-sorcery films such as Conan the Destroyer (Richard Fleischer, 1984), the trend surfaced once again in the 2010s with the action-packed Perseus chronicle Clash of the Titans (Louis Leterrier, 2010) and Wrath of the Titans (Jonathan Liebesman, 2012), and the teen updates Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (Chris Columbus, 2010) and Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters (Thor Freudenthal, 2013).

Dust to Marble

Lynda Nead has pointed out that the dream of motion has haunted visual arts from the classical period to the present, and the same can be said of the literature that spawned many of these visual representations. The fascination for breathing life into the lifeless is, of course, as old as time itself.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Screening StatuesSculpture and Cinema, pp. 137 - 155Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017