Sculpture Gallery: 150 Statues from European and American Cinema

from PART II

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2018

Summary

Vito Adriaensens and Lisa Colpaert

The following pages make up a sculpture gallery featuring a selection of 150 sculptures that play noteworthy parts in the plots or mise-en-scène of films. This selection of works and films represents the major themes and tropes that frame the encounter of sculpture and cinema. The gallery is not an exhaustive one, but rather a personal selection of works and films that we find especially interesting, chosen from a considerably longer list and focused on European and American cinema. These entries resonate with the first part of the book and also complement it, including some cin¬ematic statues found in film genres and periods that were not the focus of previous chapters, thereby providing a historical overview of key sculptural motifs and cinematic sculptures. The gallery primarily includes many fic¬tional sculptures that were made especially for films, but it also showcases a number of existing works. Some of these are the main subjects of canonical art documentaries and experimental films, including Les Statues meurent aussi (Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet, 1953), L‘Enfer de Rodin (Henri Alekan, 1957), and Ritual in Transfigured Time (Maya Deren, 1946). Animating static artworks by means of camera movement, lighting, editing, and music, these films suggest that cinema is the perfect medium for the exploration and visualization of sculptural volumes, which can be perceived from various or shifting viewpoints.

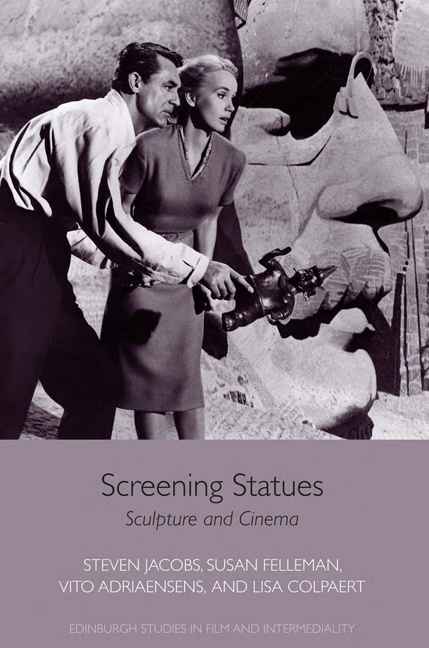

This gallery also includes some “real” sculptures that play an impor¬tant role in fiction films. Often, these are iconic statues, such as: Frédéric Bartholdi and Gustave Eiffel's 1886 Statue of Liberty, which is scaled in the epic closing scenes of Alfred Hitchcock's Saboteur (1942) and taken for a spin around Manhattan in Ghostbusters II (Ivan Reitman, 1989); Gutzon and Lincoln Borglum's Mount Rushmore National Memorial (1927–41), the location of another suspenseful altercation in Hitchcock's North by Northwest (1959); and the Vorontsov Palace marble lions (c.1830) – modeled in part after the Medici lions – that were immortalized and animated by Sergei Eisenstein's montage in Battleship Potemkin (1925). Such “real” statues retain their real world connotations but are also somewhat fictionalized when integrated into cinematic narrative.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Screening StatuesSculpture and Cinema, pp. 171 - 250Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017