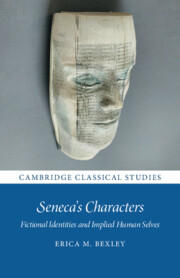

Now that we have come to the end, I would like you to turn back, dear reader, to the front cover of this book, or, in the more likely event of your reading it in digital form, to scroll back to the top. Take a close look. The image is of a face carved from the pages of an old volume, a piece of art combining the plastic forms of sculpture and mask with hints of more abstract fictional representation. As sculpture, the work’s medium and its content coincide in being fully three-dimensional: this is not a physically flat description in print, or a (slightly less flat) painting, but a material, graspable visage, and the very fact of its materiality draws a particularly close analogy to an actual human face. It is, however, a face with no back; the head stops abruptly at the book’s cover. Unlike more traditional sculpted portraits, this is not a bust, it has no neck and shoulders; it is a detached, free-floating face, and this incompleteness evokes, to my mind at least, the theatrical mask. Like a mask, this visage is purely forward-facing, it is the display of a face, the symbol of one, which somewhat – but only somewhat – belies its implied human qualities. Also like a mask, it can take on different expressions when viewed from different angles: smiling from the front; impassive from the side; troubled from above.

Most significant for my purposes, however, is the sculpture’s union of recognisably human features with a recognisably textual medium. It is made not just from paper, but from words on printed pages. This is a face that can quite literally be read, although to do so would mean having to approach so close to the work that one would lose sight of its form. A few steps back and the opposite occurs: the pages and words grow indistinct, merely instrumental to the image arising from them. Writing morphs into a face and that face dissolves back into writing.

I am sure you will have guessed by now, so I shall state it outright: this sculpture is a metaphor for the qualities of fictional character explored in this book. As a visage emerging from printed text, it encapsulates fictional characters’ duality of literary fabrication and implied human being, the recognisably ‘human’ characteristics that are sometimes undercut, sometimes complemented by the medium that gives them life. The character qua person comes out of the words, is built from the words, but also seems like more than the simple sum of those parts. It is easy for audiences to forget sometimes that the text is there, just as viewers can see the face without necessarily, momentarily, seeing the book. In both instances, though, the text is indispensable.

The sculpture’s evocation of a mask is likewise significant for my project, as a reference to the theatrical dimension of Seneca’s characters, for whom performance represents both an expansion and a diminution of humanness. On the one hand, the dramatic medium holds out the promise of corporeal reality, subjectivity, and agency, while on the other, it curbs individual autonomy and reduces the body to a spectatorial object. In similar fashion, the sculpture offers to viewers both a face and a symbol, the suggestion of embodiment coupled with the brute fact of its object status. The mask is at once an instrument and a second layer of skin.

The dialogue traced in this book between character in its textual and mimetic modes is by no means restricted to Seneca, but it is something Seneca’s work expresses especially powerfully. As a writer of philosophic prose as well as dramatic verse, moreover, as a philosopher chiefly interested in ethics, Seneca is ideally placed for a study that deals with the contours of fictional human beings, their relationship to their literary medium and tradition, and to actual models of human behaviour. Beyond this happy coincidence, though, is Seneca’s independent and distinct tendency to blur character’s two modes throughout his dramatic work, so that audiences do not have to minimise one in favour of the other, to experience the work only at the intradramatic level and not the extradramatic one, or vice versa. Rather, Seneca’s dramatis personae tend to draw on both modes simultaneously, to the same ends: coherence is both a moral and an aesthetic trait; vengeance, like acting, is an expression of individual agency; the exemplary replication that confers biological authenticity resembles a process of artistic reproduction, of making copies rather than originals. This intricate layering is a conspicuous aspect of Seneca’s style; it is what makes his dramatic creations so potent and makes their impressions last long after we have closed the book, or they have retreated backstage.