Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Elizabeth's other isle

- 1 Spenser's Irish courts

- 2 Reversing the conquest: deputies, rebels, and Shakespeare's 2 Henry VI

- 3 Ireland, Wales, and the representation of England's borderlands

- 4 The Tyrone rebellion and the gendering of colonial resistance in 1 Henry IV

- 5 “A softe kind of warre”: Spenser and the female reformation of Ireland

- 6 “If the Cause be not good”: Henry V and Essex's Irish campaign

- Notes

- List of works cited

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture

4 - The Tyrone rebellion and the gendering of colonial resistance in 1 Henry IV

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 December 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Elizabeth's other isle

- 1 Spenser's Irish courts

- 2 Reversing the conquest: deputies, rebels, and Shakespeare's 2 Henry VI

- 3 Ireland, Wales, and the representation of England's borderlands

- 4 The Tyrone rebellion and the gendering of colonial resistance in 1 Henry IV

- 5 “A softe kind of warre”: Spenser and the female reformation of Ireland

- 6 “If the Cause be not good”: Henry V and Essex's Irish campaign

- Notes

- List of works cited

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture

Summary

When, at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the King of Scotland's brother, Edward Bruce, was crowned King of Ireland, “there was in prospect something very like a pan-Celtic alliance against the English” in which Scots, Irish, and Welsh would join forces around “their ‘common national ancestry,’ their ‘common language’ and their ‘common custom’.” Edward Bruce died in 1318, effectively ending hopes of an alliance at this time, but English anxieties about a coalition among Irish, Welsh, Scots, and other “outlandish” peoples remained a vestigial part of the national psyche. These anxieties surfaced again early in the fifteenth century when Owen Glendower sought Scottish support for his anti-English rebellion, thus infusing it with an air of “racial conflict.” By the later sixteenth century, fears of anti-English collusion focused upon the Scots–Irish mercenaries and Redshanks (“Scottish Irishmen”) who assisted their rebellious kinsmen in the north of Ireland. The English authorities also suspected that the rebellion in Ireland was fuelling broader structures of anti-English collaboration. Fears that Welsh malcontents were in league with Irish rebels were based in part on English awareness of the residual popularity of Catholicism in Wales and the conviction that Catholics would naturally support fellow Catholics. During an invasion alarm in 1594, the president of the council in the Marches of Wales was instructed to keep all “the more dangerous recusants … at least twelve miles from the coast,” to prevent them from giving assistance to a Spanish force, while in 1597 a Spanish observer, anticipating an invasion through Wales, claimed that at Milford Haven “There are many Catholics and the people are naturally enemies of the English and do not speak their language.”

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

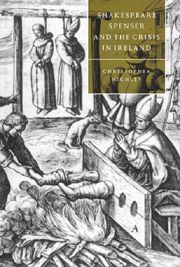

- Shakespeare, Spenser, and the Crisis in Ireland , pp. 86 - 109Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1997

- 1

- Cited by