The anarchists are and will be thus always very few, but they are everywhere. They are what I will call the leaven which raises the bread. Already, you see them involved everywhere … in the Free-thought Movement, in the Socialist Party … the trade unions, the co-operatives, they are everywhere. … There are even those who are unaware of it! Because once one explains to them what is anarchism, they say: “But if it is that, I am anarchistic! I am with you!”

Her development, her freedom, her independence, must come from and through herself. First, by asserting herself as a personality, and not as a sex commodity. Second, by refusing the right to anyone over her body.

This chapter will introduce the five theses that the social anarchist philosophical position comprises. No individual thesis is entirely original to the anarchist position; rather, they have been drawn from other philosophical camps, particularly the political philosophies advanced by libertarians and egalitarian socialists. However, the principles have been adjusted in various ways so as to render them more precise and plausible. The subsequent sections will present the five anarchist principles, explain how and why they differ from their more standard formulations, and defend their plausibility. Specifically, the chapter will begin with the principles typically endorsed by libertarians (Sections 1.1–1.3) before turning to the anti-propertarian and egalitarian theses that set social anarchism apart from standard libertarianism (Sections 1.5 and 1.6). It will also devote three sections (Sections 1.4, 1.7, and 1.8) to defending the anarchist interpretation of the self-ownership thesis presented in Section 1.3. The remaining anarchist theses will then be defended in subsequent chapters of the book.

1.1 The Consent Theory of Legitimacy

The first anarchist thesis is the consent theory of legitimacy, which holds that a state – or, more generally any agent – is legitimate with respect to its purported subjects if and only if they have consented to its legitimacy. This just-mentioned legitimacy relation can be understood as follows: Some person P is legitimate with respect to another person Q if and only if P has the Hohfeldian power to determine what obligations Q has via the issuing of edicts.Footnote 1 More specifically, P is legitimate with respect to Q if and only if Q is obligated to obey P’s edicts, where “P’s edicts” designates nonrigidly. Thus, if a state is legitimate with respect to Q and it enacts some law L at time t that mandates that Q ϕ, then Q is obligated to ϕ at t. By contrast, had the state instituted law M (rather than L) mandating that Q ψ, then Q would have been obligated to ψ at t rather than ϕ. Alternatively, one might say that P is legitimate with respect to Q if and only if when P issues an edict that Q must ϕ, Q is obligated to ϕ because P issued the edict. However, the counterfactual analysis of legitimacy is a bit clearer, so it will be favored for these purposes. The consent theory of legitimacy, then, maintains that P is legitimate with respect to Q if and only if Q has consented to being bound by P’s edicts in this way (where Q consents to some state of affairs only if she intends to consent to it, is reasonably informed about what she is consenting to, can refuse consent without incurring undue costs, etc.).

There are a few things to note about this account of legitimacy. First, legitimate states possess a Hohfeldian power to impose obligations, where, going forward, the term “legitimacy” will be used to denote this power (as well as the abstract relation that obtains between a legitimate agent and her subject). Second, the notion does not discriminate between states and private individuals: Either kind of agent can possess the power in question and, thus, be legitimate vis-à-vis some person or people. One reason for not distinguishing between state legitimacy and private legitimacy is that it is surprisingly difficult to provide an analysis of statehood that can satisfactorily demarcate states from non-state actors. This point will be discussed in detail in Section 7.2. Additionally, the suggestion here is that it is the power that is of moral significance rather than the bearer of that power, where this implies that the possession of that power is subject to the same theoretical constraints irrespective of who possesses it. In other words, if there is something problematic about a state possessing legitimacy without consent – as the consent theorist insists that there is – there will equally be something problematic about a private individual possessing this power without consent, as it is the mere possession of the power that must be justified by consent, not the fact that a state possesses this power.

Third, note that agents cannot be legitimate tout court; rather, they can only be legitimate with respect to some particular person. Thus, when one asserts that a state is legitimate with respect to a group of people, what is being asserted, strictly speaking, is that the state is legitimate with respect to each individual member of the group (unless the group qualifies as a group agent, in which case the state might be legitimate with respect to that agent). One might supplement this notion of legitimacy with a derivative scalar concept designed to capture the broader relation between the state and the aggregation of its claimed subjects. For example, to elaborate on a proposal from John Simmons (Reference Simmons2001, 130), one might say that a state is more legitimate on balance than another if and only if it is legitimate with respect to a larger proportion of its claimed subjects. However, while this notion might be useful in certain evaluative contexts, it is irrelevant to the consent theory of legitimacy, as consent theory posits a necessary and sufficient condition of the more primitive legitimacy relation obtaining between two agents.

Finally, this analysis of legitimacy differs in various ways from how others have defined the term. On one popular account, a legitimate state is one that has a Hohfeldian permission to make and coercively enforce rules (Wellman Reference Wellman1996, 211–12; Huemer Reference Huemer2013, 5). By contrast, the concept is here defined as the power to impose obligations by making rules. It, is thus, closer to what Huemer labels “political authority,” where a state possessing this property has both a permission to coerce (what he calls “legitimacy”) and a right that its subjects obey its rules (Reference Huemer2013, 5). However, note that, if one plausibly assumes that the obligations in question are coercively enforceable, a state’s power to impose obligations via edicts will entail that it has a permission to coercively enforce those edicts. Additionally, if one thinks that it is permissible to coerce someone to do something only if she is obliged to do it, then a state will have the power to impose obligations by issuing edicts if and only if it has a permission to coercively enforce those edicts – that is, what Wellman and Huemer call “legitimacy” turns out to be materially equivalent to the notion of legitimacy posited here.

It is also worth contrasting the proposed notion of legitimacy with Simmons’ (Reference Simmons2001) influential definition of the term. According to Simmons, legitimacy is a “complex moral right … to be the exclusive imposer of binding duties on its subjects, to have its subjects comply with these duties, and to use coercion to enforce the duties” (Reference Simmons2001, 130). This definition is a bit puzzling, as it seems like a category mistake to say that someone can have the right to be something rather than do something. One might interpret Simmons as suggesting that a legitimate authority has a claim against others imposing binding duties on its subjects – that is, against them exercising their power to oblige others. However, it seems more parsimonious to take Simmons to be simply asserting that if an authority has the power to oblige its subjects, then no other authority has this same power.Footnote 2 By contrast, the proposed account of legitimacy does not demand exclusivity in this way, with it being possible for multiple authorities to be legitimate with respect to the same person.Footnote 3

In short, the proposed analysis of legitimacy does not refer to any permission to coercively enforce duties and it also does not entail that only one agent can be legitimate with respect to any particular person (contra Wellman, Huemer, and Simmons). Rather, it limits itself to the assertion that an authority is legitimate if and only if that authority possesses the power to oblige via the issuing of edicts. Thus, the consent theory of legitimacy should be understood as asserting that consent is a necessary and sufficient condition of this moral power obtaining, with the book’s subsequent arguments for consent theory (presented in Sections 2.4 and 4.2) supporting this posited interpretation.

The final thing to note about the consent theory of legitimacy is that (practically) no people have actually consented to being governed, either by states or by others.Footnote 4 In other words, the necessary condition of legitimacy obtaining is (almost) never satisfied and, thus, there are no existing legitimate states or other authorities – at least, vis-à-vis the vast majority of the human population. This is not to say that there are necessarily no legitimate states. In fact, the consent theory of legitimacy entails that a state would be legitimate vis-à-vis all of its claimed subjects if, as a contingent matter of fact, they all happened to give it their consent to be governed. However, in the actual world, existing states are not legitimate with respect to practically any of their citizens; that is, they lack the power to impose obligations on their citizens by passing laws or issuing other edicts. This conclusion – a position known as philosophical anarchism – is a fitting implication of the anarchist position’s affirmation of the consent theory of legitimacy.

1.2 The Lockean Proviso

The second component of the social anarchist position is an endorsement of a particular interpretation of what has become known as the Lockean proviso. As a bit of context, libertarian property rights theorists typically maintain that the world starts out unowned such that all persons have a permission to use all things. Persons then carry out acts of initial appropriation whereby they convert those resources into private property – that is, they acquire a robust set of rights and powers vis-à-vis the appropriated objects. These rights include Hohfeldian permissions to use the owned thing; claims against all others using the thing; powers to waive these claims; immunities against the loss of these claims, permissions, and powers; and powers to transfer all of these listed rights to others.Footnote 5 Libertarians also uniformly hold that people can unilaterally carry out these acts of appropriation – that is, they do not need others’ consent in order to successfully appropriate some unowned resource. That said, many libertarian theories also include a proviso limiting the extent to which any given person can appropriate.Footnote 6 Most famously, right-libertarians adopt a particular interpretation of Locke’s contention that a person can appropriate some resource only if “there is enough and as good left in common for others” (Reference Locke2005, §33). Typically, they interpret Locke’s proviso as a non-worsening condition: To be left with “enough and as good” is to be left no worse off than if the act of appropriation had not occurred – or, more permissively, to be no worse off than if no appropriation by anyone ever occurred (as was proposed by Nozick Reference Nozick1974, 181).Footnote 7 Additionally, the proviso is taken to be not only a necessary condition of appropriation occurring via some suitable act but also a sufficient condition of that act successfully appropriating the thing in question.Footnote 8 Together, these interpretations yield (a preliminary statement of) the Lockean proviso (or “the proviso” for short): A person is able to appropriate some unowned resource via some suitable action if and only if her doing so does not leave anyone worse off.Footnote 9

Given that the proviso is a signature commitment of right-libertarianism, it may seem odd that it would be included within the social anarchist position, as right-libertarians famously reject the kind of distributive egalitarianism that will be endorsed subsequently. However, the anarchist position will incorporate this proviso for three reasons. First, the proviso’s proposed non-worsening condition is independently plausible. Specifically, it seems plausible that, by improving someone’s situation via some action – or, at least, not worsening it – one nullifies that person’s grounds for complaint about that action, where such grounds for complaint are both necessary and sufficient for precluding successful appropriation. After all, if no one is affected (on net) by the successful appropriation of some resource, then how could anyone object to that appropriation occurring? Further, if no one can reasonably object, then why should a theory of property disallow such appropriation?

Second, Chapter 2 will argue that the Lockean proviso follows from a plausible meta-principle (the moral tyranny constraint) that constrains which moral theories qualify as acceptable. The aim of this book is to derive the entire anarchist position from this meta-principle; thus, the fact that the principle entails the Lockean proviso is a decisive reason for including the proviso in the anarchist position. Finally, including the proviso in the anarchist position gives the anarchist dialectical leverage against right-libertarians who similarly endorse the proviso. As noted in the Introduction, Chapters 3 and 5 will argue that a commitment to the proviso surprisingly entails that one must deny the existence of external private property and, instead, endorse the egalitarian position presented in Section 1.5. Thus, the inclusion of the proviso in the anarchist position helps to advance an argumentative strategy that aims to challenge right-libertarianism on its own terms.

Developing this argument will be the task of the remaining chapters of this book. For now, though, the aim is strictly to give the proviso determinate content by specifying its multiple ambiguous terms.Footnote 10 Some of these terms will be left underspecified such that others can fill in the details with their own preferred theories. For example, one must ultimately specify the respect in which others must not be left worse off by appropriation. The dominant position among the proviso’s proponents is that welfare is the relevant metric to employ when making this assessment.Footnote 11 However, for the purposes of this book, one can remain neutral on this point and allow that there might be other ways in which a person can be left worse off beyond having her welfare diminished (for this reason, this book uses the placeholder “diminished advantage” to denote a person being left worse off in the relevant respect).Footnote 12 By contrast, the anarchist position does endorse a particular specification of the comparison point relative to which persons cannot be left worse off. Specifically, it holds that the appropriation of some resource succeeds if and only if such appropriation would not leave anyone worse off relative to the closest possible world where the agent never existed to appropriate the resource in the first place. For example, if person Q enjoys sitting on a stretch of beach every weekend but P appropriates that beach and thereby precludes Q from using it, that appropriation would violate the proviso, as it results in Q ending up worse off than she would have been in the world without P that is most similar to the actual world.

A full defense of this specification will be presented in Sections 3.3 and 3.4. For now, this section will turn to specifying exactly what it is that cannot leave others worse off. The obvious suggestion is that it is the appropriation of the resource that cannot leave others worse off, where appropriation is the change in normative fact that occurs when non-appropriators go from having a permission to use the resource to an obligation to refrain from using that resource. However, it will now be argued that this natural interpretation of the Lockean proviso is implausible because it is trivially satisfied by all possible appropriations. Note that if initial appropriation makes strictly normative changes to the world, altering moral facts about what rights people have over objects, then it is unclear how an act of appropriation could have any causal effect on people’s advantage. Given the physical nature of causation, it is odd to suggest that changes in nonphysical moral fact could cause physical events of the kind presupposed by the natural interpretation of the proviso. Or, to put this point another way, the causal relation has events as its relata, where events are best understood as either spatiotemporal things or, more controversially, things that are either spatiotemporal or mental.Footnote 13 Given that a change in moral fact is neither a spatiotemporal event nor a mental event, it follows that initial appropriation cannot cause people to be worse off. This, in turn, implies that the proviso is trivially satisfied by any act of initial appropriation.

It might be objected that this account of causation is too stringent. Instead, one might propose the following counterfactual account of causation: A fact of any kind C causes some other fact E to obtain if and only if (i) C and E are sufficiently distinct (e.g., they are nonidentical and, insofar as facts have parts, neither is a part of the other) and (ii) if C had not obtained then E would not have obtained.Footnote 14 This account would make it metaphysically possible that initial appropriation causally affects others’ levels of advantage, as the difference in moral fact between the appropriation world and non-appropriation world might be accompanied by a counterfactual difference in advantage. However, the proponent of this suggestion would still need to provide some argument as to why this is more than a mere possibility. Most plausibly, she might posit that human minds are sensitive to moral facts such that people form beliefs in response to those facts and then act on those beliefs.Footnote 15 This would allow her to maintain that if the moral facts had been different due to an act of appropriation not occurring, then people would have formed different beliefs, behaved differently, and thereby had a different effect on others’ advantage. Thus, a counterfactual difference in advantage would obtain, thereby giving initial appropriation causal purchase in the physical world.

The problem with this argument is that, even if one accepts this unconventional account of causation, the responsiveness of minds to moral facts is limited at best. If minds were highly sensitive to moral facts, one would expect to see wide and enduring consensus about the truth of most moral propositions. However, there is persistent and widespread moral disagreement across time and region. Thus, at most, there is a highly inelastic relationship between moral beliefs and facts such that some people eventually come to have beliefs that correspond to the facts. Given the loose connection between moral fact and human action, there is no reason to think that any given act of initial appropriation will entail a counterfactual difference in advantage-affecting behavior.

Appropriation’s lack of causal power entails that one must reject any specification of the proviso that holds that it is the appropriation itself that must not leave others worse off. Such a specification would render the Lockean proviso trivially satisfied: Even if one person exhaustively appropriated all existing resources, she would not diminish others’ advantage, as the moral change would not have any causal effects whatsoever. Given that such a permissive proviso is both implausible and fails to express the idea that motivates it – namely, that, absent any proviso, certain appropriations would leave others worse off in a way that is theoretically problematic – some other specification is needed.

Fortunately, there is an alternative specification of the Lockean proviso that seemingly captures the motivation for building the proviso into a theory of property. This version of the proviso asserts that a person can appropriate some thing via some suitable action if and only if full compliance with her established claim rights would not leave others worse off than they would have been had she not existed to establish these claims (assuming that others similarly comply with the other demands of morality). Unlike the natural interpretation of the proviso, this interpretation is not trivially satisfied, as there will be cases where compliance with property claims would leave others worse off in this way. Additionally, it seems to capture the thought that motivates the proviso, namely, that there is something morally problematic about imposing costs on fully compliant people – and, thus, a moral theory should not license the imposition of such costs.Footnote 16 The natural interpretation of the proviso errs by articulating this thought in terms of the (nonexistent) causal effect of the obligations imposed by appropriation. However, this mistake can be corrected by simply stating the proviso in terms of the costs imposed by full compliance with those obligations.Footnote 17

In addition to these three bits of specification, one further amendment to the standard Lockean proviso is needed to yield the complete anarchist interpretation of the proviso. So far it has been proposed that a suitable act of appropriation succeeds if and only if its established claims do not leave anyone worse off under conditions of full compliance (relative to the world where the appropriator did not exist). However, note that initial appropriation does not just establish claims but also the power to waive the established claims. This fact is significant because those committed to the proviso must seemingly also affirm that the exercise of this power must not leave others worse off under conditions of full compliance. Otherwise, the endorsement of the proviso seems arbitrary: Why would one power to change others’ permissions vis-à-vis the use of natural resources (via appropriation) be subject to a non-worsening constraint but not another such power (namely, the power to waive)? In other words, if one holds that a person can appropriate some resource only if no one is left worse off as a result under conditions of full compliance, one should also hold that a person can waive her property rights only if that act similarly leaves no one worse off under conditions of full compliance.Footnote 18

Further, note that initial appropriation is generally taken to establish both rights against others using the owned thing and the power to waive these rights – that is, appropriation is a sufficient condition of the power to waive. However, if this is correct, then any necessary condition of the power to waive must also be a necessary condition of successful appropriation (for, if p entails q and q entails r, then p entails r). Given that the owner of some resource can possess the power to waive her rights over that resource only if no act of waiving would leave anyone worse off under conditions of full compliance, it follows that she can appropriate the thing only if no subsequent waiving of her rights would leave anyone worse off under conditions of full compliance. Thus, one must build this restriction into the Lockean proviso by restating it as follows:

The Lockean Proviso – A person appropriates some unowned resource via some suitable action if and only if (a) her established claims would not leave anyone worse off under conditions of full compliance and (b) no subsequent waiving of those claims would leave others worse off under conditions of full compliance (where, in both cases, the baseline for comparison is the closest possible world where the appropriator did not exist).

This statement of the proviso is still in need of slight revision for reasons that will be discussed in Section 3.4. Thus, technically speaking, this is not the official anarchist interpretation of the Lockean proviso. However, it has the virtue of being comparatively straightforward and easy to grasp while still being quite proximate to the final version of the proviso. For this reason, it will be left to stand here as the primary statement of the proviso that is affirmed by the social anarchist position.

1.3 The Self-Ownership Thesis

The third component of the social anarchist position is a qualified endorsement of the self-ownership thesis. This signature libertarian thesis asserts that each person has the same set of rights over her own body that she would have over a fully owned thing, including a permission to use her body, a claim against others using her body, a power to waive this claim, an immunity against the loss of any of these listed rights, and a power to transfer them to others.Footnote 19 These rights are then taken to entail a number of attractive moral conclusions. For example, a claim against use implies that a person is wronged if someone harvests her organs and redistributes them to other people. It also implies that persons have correlative duties to refrain from attacking or sexually assaulting self-owners. Additionally, this right to exclude others from using one’s body is typically taken to imply the permissibility of abortion, as fetuses who use a pregnant person’s body without consent infringe on this right (with abortion then becoming a form of permissible self-defense).Footnote 20 Proponents of the self-ownership thesis also maintain that the permissions to use one’s body entail the negation of (nonconsensual) moral slavery – that is, when one person possesses the moral rights that correspond to the legal rights of slave owners (including a permission to act on the slave’s body in whatever way the owner likes as well as a power to oblige the slave to act in whatever way the owner chooses) – as well as various Millian liberties such as the permission to use drugs or the permission to have consensual but socially disapproved of sex.Footnote 21

The anarchist endorsement of the self-ownership thesis is qualified in two important ways. First, contra the standard self-ownership thesis, it does not hold that all persons possess self-ownership rights (prior to waiving or forfeiting those rights). Rather, it allows that some people might lack these rights without having ever possessed them in the first place. This is because the proposed anarchist position posits that self-ownership is not native in the sense that persons start out with self-ownership rights as soon as they satisfy the sufficient conditions for moral personhood. Rather, it holds that persons must acquire ownership of their bodies – and must do so in just the same way that they would acquire property rights over any unowned resource, namely, via acts of initial appropriation. Call these acts of self-appropriation.

There are two reasons for favoring the view that self-ownership is acquired rather than native. First, the latter view seems unacceptably arbitrary. As the initial definition of self-ownership (at the start of this section) suggests, proponents of the self-ownership thesis take the ownership of one’s body to be of a kind with the ownership of any other object or resource. Given this similarity, it is odd to insist (as most self-ownership proponents do) that the ownership of all external things is established via acts of initial appropriation while the ownership of the body is simply a correlate of personhood. This posited difference seemingly demands explanation; however, it is not clear how property theorists can provide such an explanation while continuing to insist that persons own themselves in the same way that they would own anything else. For this reason, it seems better to treat like things alike by maintaining that self-ownership is acquired via self-appropriation.

The second reason for favoring this approach is that it might help to resolve a worry about the kind of moral equality presupposed by the proponents of native self-ownership. Briefly, those who affirm the self-ownership thesis posit that each self-owner starts out with the same set of rights as all other self-owners. At the same time, these rights are denied to all nonpersons including very young children, animals, plants, rocks, photons, etc. Further, the apparent reason that these nonpersons are denied self-ownership rights is that they lack certain cognitive capacities that moral persons possess.Footnote 22 However, note that cognitive capacity is scalar, and different people will possess any given capacity to different degrees. By contrast, the self-ownership thesis assigns rights in a binary fashion: An individual either possesses the specified set of rights or she does not. As a result, the proponent of moral equality faces two related challenges. First, she must explain why self-ownership rights are not also assigned in a scalar fashion such that persons who have greater cognitive capacities possess proportionately more rights (or weightier rights). Second, she must (a) posit some specific capacity threshold that divides self-owners from nonpersons where (b) this division is nonarbitrary such that she will be able to justify why two individuals who differ only minutely in cognitive capacity – but who happen to fall on either side of the threshold – have very different rights while two individuals who differ significantly in cognitive capacity but are both above (or below) the threshold possess the same set of rights.

While there have been various attempts to address these challenges, assessing their merits would take things too far afield. Rather, the aim here is merely to show that the proponent of self-appropriation can offer a promising alternative reply to the two challenges and thereby provide a novel reason for thinking that self-owners all have the same set of rights (prior to waiving, transfer, and forfeiture). Specifically, note that the proposed theory of self-appropriation does not appeal to cognitive capacities to explain why moral persons possess self-ownership rights while nonpersons do not. Instead, it holds that individuals possess these rights in virtue of having exercised their respective powers to appropriate resources. Thus, it sidesteps the first challenge to moral equality because the binary property of possessing self-ownership rights is now a function of another binary property, namely, the property of having performed a suitable act of self-appropriation. Similarly, it resolves the second challenge to moral equality because one can explain why two people might have very similar capacities but only one possesses self-ownership rights: The self-owner has carried out an act of self-appropriation while the other person has not.

Granted, one must still answer the question of why some people have the power to appropriate while others (very young children, cats, etc.) do not. And, given that the answer to this question must seemingly appeal to differences in cognitive capacity, one might reasonably worry that the aforementioned proposal simply passes the buck, as one must still ground a binary normative property (the possession of the power to appropriate) in a scalar property (the degree of cognitive capacity possessed). However, the suggestion here is that it is easier to meet the two previously presented challenges if the normative property in question is possessing the power to appropriate as opposed to possessing self-ownership rights. Recall that the first challenge for proponents of native self-ownership is to explain why ownership should not also be treated as scalar, with persons receiving rights in proportion to their cognitive capacities. While perhaps such an explanation can be provided, the proponent of self-appropriation has an easier response to this challenge: Unlike the possession of ownership rights, the possession of the power to appropriate simply cannot be treated in scalar fashion, as it is strictly a binary property. The reason that ownership can be treated as scalar is because it is really a bundle of distinct rights that can be disaggregated and then assigned in proportion to persons’ respective cognitive capacities. By contrast, the power to appropriate is not an aggregate of more basic Hohfeldian incidents that can be unbundled and assigned in a scalar fashion. Thus, the proponent of self-appropriation does not face any analogous challenge of explaining why the possession of the power to appropriate is not proportionate to cognitive capacity.Footnote 23

What about the challenge of positing a nonarbitrary capacity threshold that divides those who are able to self-appropriate from those who lack this power? Here, again, the proponent of self-appropriation seems better positioned to resolve this challenge than those who contend that self-ownership is native. Specifically, she can propose a nonarbitrary threshold by appealing to her account of which acts qualify as acts of initial appropriation: A person is able to (self-)appropriate if and only if she has the requisite cognitive capacities to carry out an act of initial appropriation. For example, Carol Rose proposes that persons appropriate unowned resources by asserting that they own the resources in question (Reference Rose1985, 81). Thus, someone would be able to self-appropriate if and only if she both possesses the capacity to make assertions and grasps the relevant concepts of ownership such that she can meaningfully assert that she owns her own body. Such a proposal would simultaneously (a) provide a nonarbitrary threshold demarcating potential appropriators from those who are unable to appropriate, (b) plausibly entail that young children and animals are not able to appropriate, and (c) plausibly entail that practically all human adults are able to self-appropriate. Additionally, given that practically every person has, at some point, asserted that her body belongs to her, the account would entail that all persons have carried out acts of self-appropriation.Footnote 24 Thus, assuming that these acts satisfy the Lockean proviso – which, as Chapter 3 will argue, they necessarily do – it follows that practically all persons own themselves (at least, prior to waiving or transfer), even though it is at least possible that some persons never self-appropriate. In this way, the self-appropriation proponent is able to explain why persons own themselves, explain the moral equality of adult persons, explain why children and animals are excluded from the set of morally equal persons, and explain why the threshold that divides those who can self-appropriate from those who cannot is principled rather than arbitrary.Footnote 25

In addition to making self-ownership an acquired status rather than a native one, the anarchist position further qualifies the self-ownership thesis by endorsing a more permissive interpretation of the concept of self-ownership. As noted previously, one of the core self-ownership rights is a claim against others using one’s body. According to the classical interpretation of the concept of self-ownership, this claim against use is to be understood as a claim against trespass – that is, a claim against any person taking an action that makes unwanted contact with the self-owner’s body.Footnote 26 By contrast, the anarchist interpretation of self-ownership limits this right to exclude by permitting bodily contact that uniquely generates supplemental benefit:

ASO – Each self-owner has a right against any other person taking any action that (a) results in physical contact being made with her body and (b) does not uniquely provide anyone with supplemental benefit on net.

Predicate (b) contains a number of technical terms that are in need of explication. However, before explaining these terms and, by extension, which actions ASO forbids and which it permits, it will be helpful to, first, provide some elaboration of Predicate (a). Specifically, this predicate establishes the first necessary condition of an action infringing upon a person’s self-ownership rights: The action must cause physical contact with the self-owner’s body. There are a few things to note about this necessary condition. First, the action need not make bodily contact directly as one does with a punch or a kick. Rather, it might simply initiate a causal chain that ultimately results in physical contact being made with the owned body. Second, if that causal chain includes another person acting in a way that causes the contact – where an alternative action by that person would not have caused any physical contact with the self-owner’s body – then the condition should be understood as not having been met. In such a case, it is the other person who infringes upon the self-owner’s rights, not the original agent. Finally, the infringing agent need not intend that her action results in physical contact; rather, Condition (a) is satisfied by the mere fact that the action does result in such contact.

Predicate (b) of ASO asserts a second necessary condition of self-ownership infringement (where the joint satisfaction of both Condition (a) and Condition (b) is a sufficient condition of such infringement occurring). Specifically, it holds that an action that satisfies Condition (a) infringes upon a self-owner’s rights if and only if that action does not uniquely provide anyone with net supplemental benefit – where both of the italicized terms need to be explicated if this proposition is to have clear content. With respect to the latter notion, consider an action that satisfies Condition (a) because it causes physical contact to be made with a self-owner. This action generates supplemental benefit if and only if it also benefits someone on net excluding all of the effects caused by contact with the self-owner’s body. For example, an action might generate supplemental benefit because it causes two distinct events, one of which is contact being made with a body and the other of which independently produces benefits for some person. In such a case, the resulting benefits would be supplemental benefits, as they are caused by the agent’s action but not the resulting bodily contact.

To make this proposal a bit more precise, let “A” stand for the world where the agent carries out some body-impacting action and “B” stand for any arbitrary comparison world where she does not carry out the action in question. Finally, let “C” stand for the world where the agent carries out the action but the impacted self-owner never existed (but all of the self-owner’s previously imposed costs and benefits still obtained).Footnote 27 If some person P is x units better off in A than in B, then the action benefits P relative to B. One can then determine what share of that benefit is supplemental by comparing P’s level of advantage in B to her level of advantage in C. Specifically, if P is y units better off in B, that should be taken to imply that those y units of benefit were caused by the bodily contact with the self-owner and, thus, do not count as supplemental. One can, thus, conclude that the action generates x – y units of supplemental benefit relative to B (i.e., it produces supplemental benefit if and only if x > y).

This comparison helps to clarify what it means to say that some benefit is caused by bodily contact (and is, thus, non-supplemental). Consider the case where an agent can win a race only by pushing a loiterer out of the way by opening a door. There is a sense in which the bodily contact initiated by the action causes the agent to benefit: Absent that contact she would not win the race, where these corresponding counterfactual differences imply that the contact causes her to win the race according to counterfactual theories of causation.Footnote 28 However, if one applies the proposed test, one sees that the bodily contact does not cause the agent to benefit in the sense of “cause” being employed here. This is because the agent acquires the same benefit in the world where she shoves the loiterer with the door as she does in the world where she opens the door and the loiterer never existed (i.e., y = 0). Thus, no portion of her acquired benefit is caused by the bodily contact, at least in the sense of “cause” that is being employed here; rather, the benefit is entirely supplemental. While this usage of “cause” is perhaps idiosyncratic, this is how the term should be understood in the subsequent discussion of what counts as supplemental benefit.

As we continue with the explication of Condition (b), note that this condition does not merely assert that the absence of supplemental benefit is a necessary condition of self-ownership infringement; rather, it insists that an action infringes on someone’s self-ownership rights only if it does not uniquely generate supplemental benefit. This notion is defined as follows: An action that satisfies Condition (a) uniquely generates supplemental benefit if and only if it generates benefit for some person and there is no alternative action available to the agent that would generate at least as much supplemental benefit for that person without satisfying Condition (a). In other words, if an action makes contact with a body and does not generate supplemental benefit, then it infringes on self-ownership rights. Similarly, if it does generate supplemental benefit but that benefit can be equally provided without making bodily contact, then the self-owner has a claim against the action. By contrast, if it generates supplemental benefit and there is no way to generate the same (or more) supplemental benefit without bodily contact, then the action in question is permitted by ASO.

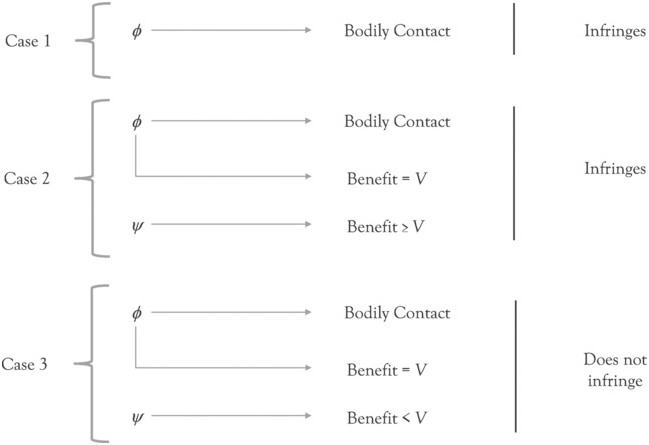

This explication of ASO is summarized in Figure 1.1, which schematically illustrates whether an action infringes upon a person’s self-ownership rights.

Figure 1.1 Causal chains and rights infringement.

In Case 1, some action ϕ causes physical contact to be made with some self-owner’s body, where this causal relationship is represented by the right-facing arrow. In this case, no supplemental benefit is generated by the agent’s ϕ-ing. Thus, the action straightforwardly satisfies both Condition (a) and Condition (b) of ASO and thereby infringes upon the self-owner’s right against others using her body.

Case 2 is identical to Case 1 except, in this case, ϕ-ing also causes someone to obtain a supplemental benefit of value V, where this benefit is supplemental in virtue of the fact that it is caused by the ϕ-ing but is not caused by the contact that is made with the self-owner’s body. However, in this case, the agent could provide the beneficiary with that same quantity of benefit and avoid bodily contact by ψ-ing instead of ϕ-ing. Given these stipulations, the agent’s ϕ-ing generates supplemental benefit beyond that caused by bodily contact, but it does not uniquely generate this benefit. Thus, ϕ-ing still meets Conditions (a) and (b) and thereby infringes upon the self-owner’s rights according to ASO.

Finally, Case 3 modifies Case 2 such that there is no longer any alternative action that can provide the beneficiary with a benefit of equal or greater value to V – that is, the quantity of supplemental benefit generated by ϕ-ing. In this case, it is stipulated that ψ is the action that provides the beneficiary with the greatest quantity of benefit relative to all actions that are not identical to ϕ. Given that this quantity is less than the quantity of supplemental benefit generated by ϕ-ing, ϕ-ing uniquely generates supplemental benefit and, thus, does not infringe upon the self-owner’s rights according to ASO.

To make this more concrete, consider the case where P discovers her roommate Q asleep on the kitchen floor. Annoyed, P decides to vent her anger by pouring a glass of water on Q’s head. Such an action instantiates Case 1: while P enjoys seeing Q jolted awake, this benefit is caused strictly by the bodily contact that she initiates (as her action of pouring the water would not produce this benefit in the world where Q did not exist). Thus, her action does not generate supplemental benefit and infringes on Q’s self-ownership rights. Alternatively, suppose that P decides to take this opportunity to clean the kitchen by starting up her robotic vacuum. P knows that the vacuum will bump into Q’s head and thereby wake her up, an outcome that P will enjoy. Additionally, P will derive satisfaction from the kitchen floor being clean. Given this latter stipulation, it follows that P derives supplemental benefit from her action beyond the benefits produced by bodily contact. However, further specification is needed to determine whether starting the vacuum uniquely produces this supplemental benefit. Suppose that P could get the same satisfaction by sweeping the floor while avoiding contact with Q. In that case, starting the vacuum would not uniquely produce supplemental benefit; that is, her action instantiates Case 2 and infringes on Q’s rights. By contrast, if P has no alternative way of cleaning the floor – for example, because no broom is available – then starting the vacuum instantiates Case 3, and Q does not have a self-ownership right against P taking that action.Footnote 29

1.4 The Advantages of Anarchist Self-Ownership

The foregoing discussion has attempted to clarify the content of ASO without providing a defense of the principle, that is, explaining why one ought to accept ASO over rival versions like the classical concept of self-ownership. While the primary argument for ASO will be presented in Chapter 3, this section will note some attractive implications of ASO, where the fact that ASO generates these implications is one reason to accept the principle. First, note that ASO appears to preserve most of the attractive implications of the classical self-ownership thesis. For example, it would still forbid the involuntary redistribution of kidneys or other organs to needy individuals, as such redistribution initiates bodily contact (thereby satisfying ASO’s Condition (a)) without uniquely generating supplemental benefit in the sense defined previously (thereby satisfying Condition (b)). Granted, the organ recipients and their loved ones would benefit from the actions in question; however, because this benefit is caused by the contact made with self-owners’ bodies, it would not qualify as supplemental benefit. Thus, ASO implies that involuntary organ redistribution infringes upon persons’ self-ownership rights. Similarly, ASO forbids agents from slapping someone to blow off steam or drawing crude images on a sleeping person for amusement, as, again, these actions make bodily contact without generating supplemental benefit. Additionally, because fetuses make bodily contact that does not generate supplemental benefits beyond those caused by the contact itself, ASO would entail that pregnant persons have a claim against the fetus using their bodies in this way, thereby opening up the possibility that abortion is permissible.

Second, ASO is able to make sense of many – though, admittedly, not all – of the standard intuitions that people have about Trolley Problem-related cases.Footnote 30 Ethicists have now put forward a large number of these cases, but the two paradigmatic ones worth considering here are the switch case and the footbridge case. In the switch case, a trolley is going to run over five people unless the agent flips a switch and redirects the trolley onto a different track where it will hit and kill one person. In this case, the standard intuition is that it is permissible to redirect the trolley.Footnote 31 By contrast, in the footbridge case, the only way to stop the trolley from killing five people is to push a person off a footbridge in front of the trolley, thereby making it grind to a halt. In this case, the standard intuition is that it is impermissible to push the person off the footbridge. The problem, then, is trying to explain why there might be this difference in permissibility despite the fact that both flipping the switch and shoving the person amount to killing one person to save five from dying.

The advantage of ASO is that it is able to provide such an explanation. Note that, in the switch case, the benefits that are generated by flipping the switch are all supplemental benefits; that is, they are caused by the action but are not caused by any bodily contact initiated by that action. Indeed, if the single person on the secondary track had never existed, the five people on the main track would be no worse off than if the trolley hit the person, where this counterfactual comparison reveals that the benefits they derive are supplemental. Further, flipping the switch uniquely generates these supplemental benefits, as there is no alternative action that would save the lives of the five people on the track. Given that flipping the switch uniquely produces supplemental benefit, the action does not satisfy ASO’s Condition (b) of self-ownership infringement. By contrast, shoving the person from the footbridge does not generate any supplemental benefits, as all of the benefits produced are caused by the contact made with her body; absent any such contact, the trolley would not stop and the five people on the track would not survive. Thus, the shove satisfies both Condition (a) and Condition (b) of ASO and thereby qualifies as a self-ownership infringement. In this way, ASO is able to explain why flipping the switch is permissible but shoving the person is not: Only the latter action violates a person’s self-ownership rights.Footnote 32

The third advantage of ASO is that it solves what, following Nicola Mulkeen (Reference Mulkeen2019), might be called the self-ownership thesis’ pollution problem. As noted previously, the classical interpretation of self-ownership assigns each self-owner a claim against others making nonconsensual contact with her body. The problem with this assignment is that it seemingly renders almost all activities impermissible. For example, a claim against all bodily contact would forbid people from protecting their crops with insecticide if the emitted aerosols would drift downwind and make contact with other people’s lungs (Railton Reference Railton2003, 190). People would also be forbidden from operating any sort of vehicle that produces particulates that land on others’ skin (Sobel Reference Sobel2012, 35). Rights-infringing particulates would not be limited to exhaust fumes; simply kicking up dust with a car would seemingly infringe on others’ self-ownership rights if the dust were to land on them (Brennan and van der Vossen Reference Brennan, van der Vossen, Brennan, van der Vossen and Schmidtz2018, 205). Even human respiration produces a form of pollution (carbon dioxide) whose contact with others might wrong them (Friedman Reference Friedman1989, 168). Similarly, because sound waves exert force on others’ bodies, the classical interpretation of the self-ownership thesis would forbid yelling at someone (Fried Reference Fried2004, 78) or driving up one’s own driveway if others will hear the rumbling (Mack Reference Mack2015, 196). Further, given that photons are particles, it would be impermissible to turn on a flashlight or start a fire if doing so would slightly illuminate another person’s body (Zwolinski Reference Zwolinski2014, 12). Even walking into another’s line of sight would seemingly wrong her, as doing so would bombard her eyes with redirected photons. Thus, the classical interpretation of the self-ownership thesis seems to implausibly entail that a huge portion of indispensable human activity is impermissible.

By contrast, ASO avoids these problematic implications by permitting actions that make bodily contact but also uniquely generate supplemental benefit. For example, when an agent operates a factory that produces particles that land on others’ skin, she is also producing material goods that will benefit others – where, presumably, there is no way to produce these goods without emitting pollutants that will make bodily contact. Thus, operating the factory does not infringe upon anyone’s self-ownership rights according to ASO. Similarly, while respiration inevitably bombards others’ bodies with carbon dioxide molecules, it would be permissible because it uniquely generates supplemental benefits for the respirator. And the same goes for actions like driving past one’s neighbors, turning on lights, etc. In each of these cases, the agent’s action bombards others’ bodies with various small particles; however, at the same time, these actions all uniquely produce benefits that are caused by the action and not the bodily contact that it initiates.Footnote 33 Given that ASO does not count such actions as self-ownership infringements, it permits the countless indispensable, everyday activities that the classical interpretation of self-ownership forbids.Footnote 34

Fourth, ASO is able to explain a number of other commonsense distinctions that people might be tempted to draw when assessing the permissibility of various activities. For example, one might want to draw a distinction between nudism (where people enjoy being naked for its own sake) and exhibitionism (where people reveal their bodies because they derive pleasure from being seen naked), with the former being judged permissible and the latter wrongful. ASO is able to support this distinction because it entails that sexual exhibitionism infringes on people’s self-ownership rights while nudism does not. To see why this is the case, note that exhibitionists make bodily contact with others because they bombard their victims’ eyeballs with photons, thereby satisfying Condition (a) of ASO. Additionally, because exhibitionists derive their enjoyment from perceiving the reaction of their victims – that is, all of the benefit produced by their action is caused by the bodily contact they initiated – their action does not generate any supplemental benefit. Given that exhibitionism also satisfies Condition (b) of ASO, it follows that it infringes upon other people’s self-ownership rights. By contrast, nudists, by hypothesis, derive unique pleasure from being naked. Thus, while they also bombard others’ bodies with photons, they get unique supplemental benefit from being naked and, therefore, do not satisfy Condition (b) of ASO. As a result, ASO entails that nudism does not infringe upon anyone’s self-ownership rights.

ASO also supports a related distinction between speech that is merely blasphemous (e.g., printing a picture of the prophet Muhammad in a history textbook) and speech that is designed deliberately to antagonize religious believers (e.g., distributing rude caricatures of Muhammad). Both kinds of speech satisfy Condition (a), as they bombard people’s bodies with photons or soundwaves. However, blasphemous speech, by hypothesis, uniquely generates some other benefit such as educating people about history. It, thus, does not violate anyone’s self-ownership rights because it does not satisfy Condition (b) of ASO. By contrast, the benefits of antagonistic speech are produced by a causal chain that passes through self-owners’ bodies: Like the exhibitionist, the antagonist gets her satisfaction from perceiving the reaction that her action elicits. In other words, the benefits produced by antagonistic speech are not supplemental benefits, with such speech thereby satisfying Condition (b) and, by extension, infringing on others’ self-ownership rights. Admittedly, many liberal and libertarian proponents of free speech will find this result objectionable; however, for those who share the intuition that there is a moral distinction between blasphemy and provocation, this result will count in ASO’s favor, as ASO provides a theoretical basis for affirming this distinction.

Finally, in addition to forbidding paradigmatic self-ownership infringements, supporting commonsense moral distinctions, and solving the pollution problem, ASO also solves a less-discussed problem with the classical self-ownership thesis, namely, that the latter fails to adequately differentiate aggressors from victims. To see why this is the case, recall that the classical interpretation of the thesis asserts that an agent wrongs a victim when she touches the victim without consent. For example, a pedestrian who punches a rapidly moving bicyclist wrongs the bicyclist by virtue of her having made nonconsensual contact with the bicyclist’s body. The problem is that, while the classical thesis yields the favorable result that the pedestrian infringes on the bicyclist’s self-ownership rights, it also entails that the bicyclist infringes on the pedestrian’s self-ownership rights – at least, if one assumes that the concept of touching is analyzed in a reasonably thin way.

To see why this is the case, suppose that one holds that P touches Q if and only if P’s body makes physical contact with Q. This very thin physicalist analysis of touching entails that the pedestrian touches the bicyclist, as physical contact is made between their bodies; however, given this contact, the analysis of touching also implies that the bicyclist touches the pedestrian. Further, given that the touching relation is symmetrical on this account, the standard self-ownership thesis would deliver the seemingly incorrect result that the bicyclist infringes on the pedestrian’s rights when her face makes unconsented-to contact with the pedestrian’s fist.

To correct for this problem, one might insist upon a thicker analysis of touching that makes reference to not only physical contact but also various counterfactual considerations. Specifically, one might suggest that P touches Q if and only if their bodies make contact and a different choice by P would have resulted in their bodies not making such contact. This proposal is promising in that it opens up the possibility of the touching relation being asymmetrical, as it possible that only one party could have avoided physical contact by making a different choice. Additionally, one might think that this thicker account supports the intuition that it is the pedestrian (not the bicyclist) who does the touching given that no bodily contact would have occurred had the pedestrian chosen not to punch the bicyclist. However, this proposal does not, in fact, deliver the desired asymmetry, as the bicyclist could equally have chosen in a way that avoided the contact (e.g., she could have ridden in the other direction). Thus, the thicker account still yields the result that the bicyclist touches – and thereby wrongs – the pedestrian.

The general conclusion to draw from this discussion is that proponents of the self-ownership thesis cannot assume that there is some pre-theoretical fact of the matter about who touches whom. Rather, they need to either provide an even thicker analysis of touching or adopt the thin analysis and modify the self-ownership thesis to limit which touchings qualify as infringements. Otherwise, they will be unable to correctly differentiate aggressors from victims. ASO represents the latter approach to solving this problem, as it restricts the set of contact-initiating acts that qualify as rights infringements in a way that allows for aggressors to be suitably demarcated from victims. Notably, while mere contact is a symmetrical relation, contact without supplemental benefit can be asymmetric: When two persons come into contact, that contact might be the product of one person acting in a way that generates supplemental benefit while the other’s action produces no such benefit. For example, when the bicyclist makes contact with the pedestrian, this contact is the result of her carrying out an action (riding her bike somewhere) that uniquely generates supplemental benefits (getting where she is going in the most efficient way). By contrast, the pedestrian’s action does not produce any supplemental benefit, as the only benefit she gets is the satisfaction caused by the physical contact . Thus, ASO entails that the pedestrian infringes on the bicyclist’s self-ownership rights by punching but the bicyclist does not infringe on the pedestrian’s rights by taking her trip. In this way, ASO is able to adequately differentiate aggressors from victims in a way that the classical interpretation of the self-ownership thesis cannot. This is an additional theoretical advantage for the proposed principle.Footnote 35

This is not to say that ASO does not also have its theoretical drawbacks. For example, Sections 1.7 and 1.8 will consider (and try to ameliorate) worries that it is both too permissive and also too restrictive. However, the hope here has been to show that the anarchist interpretation of self-ownership has much to recommend it, where these advantages must be weighed against the soon-to-be-discussed theoretical disadvantages. Additionally, in Chapter 3 will be argued that there is a supplemental reason for endorsing ASO beyond its attractive implications, namely, that it is the kind of self-ownership that persons can acquire in accordance with the Lockean proviso.

1.5 The Rejection of Private Property

The fourth component of the anarchist position is fairly straightforward, and, thus, requires limited exposition. Specifically, it holds that, while many people own their own bodies in virtue of having self-appropriated, there have been practically no successful appropriations of external unowned resources and nor will there be more than a handful of such appropriations in the future. In other words, practically no one has – or ever will have – any private property rights over any external thing, be it land, objects, or other natural resources.Footnote 36

It is this conclusion that sets social anarchism apart from libertarian views, all of which posit that most things are privately – or, at the very least, collectively – owned.Footnote 37 Up to this point, the proposed anarchist theses have all been paradigmatic libertarian positions (albeit with a few heterodox adjustments having been made to them). However, no self-identified libertarians endorse the view that all natural resources are unowned. Rather, the rejection of private property is a signature commitment of socialist philosophical positions, where socialism and libertarianism are generally taken to be diametrically opposed views. One might therefore worry, that the inclusion of this thesis in the social anarchist position renders the view incoherent. The aim of Chapters 3 and 4 is to show that this is not the case and that, in fact, the anarchist denial of property rights follows from the libertarian theses presented previously.

1.6 Anarchist Claim Rights

While the anarchist holds that no one owns ‒ or could come to own ‒ practically any natural resources, this does not commit her to the view that persons are free to do whatever they like with these resources. Rather, she insists that a luck egalitarian principle of distributive justice determines which uses of those resources are permissible and which are forbidden. Specifically, she assigns persons distributive claims over unowned resources and objects, where these claims correspond to the prescriptions of a luck egalitarian principle of distributive justice. This section will introduce the luck egalitarian theory of justice and then explain what it means to say that persons have distributive claims corresponding to this theory.

To introduce the luck egalitarian theory of distributive justice, it is helpful to contrast it with what might be called a strict egalitarian view. According to the strict egalitarian, a distribution of resources is just if and only if everyone has equal advantage, where “advantage” refers to whatever it is that matters as far as justice is concerned.Footnote 38 For example, one might implausibly take advantage to be the total number of calories that a person has consumed, with justice obtaining if and only if every person has consumed the same number of calories. More plausibly, one might take advantage to be a quantity of money such that justice requires that all persons have equal wealth. More plausibly still, one might take “advantage” to refer to the amount of welfare that a person experiences either over some specified interval of time or over the course of her entire life. For these purposes, it will be assumed that what is to be equalized ‒ that is, the equilisandum or, alternatively, the currency of egalitarian justice ‒ is the quantity of welfare experienced across a lifetime. This assumption is made because it seems intuitively plausible and will simplify some of the subsequent discussion (though no derived conclusions depend on it). However, it is worth emphasizing that both strict egalitarianism and luck egalitarianism are neutral with respect to what it is that must be equalized. For this reason, the book will use the ambiguous term “advantage,” thereby allowing for those with rival views about the proper currency of egalitarian justice to specify luck egalitarianism as they see fit.

In contrast to strict egalitarianism, luck egalitarianism does not insist that justice requires an equal distribution of advantage. Rather, luck egalitarians are willing to declare certain inequalities just if and only if those inequalities correspond to some choice for which the worse-off parties are responsible. For example, Cohen provides a representative statement of the luck egalitarian position when he asserts that “an unequal distribution whose inequality cannot be vindicated by some choice or fault or desert on the part of (some of) the relevant affected agents is unfair, and therefore, pro tanto, unjust” (Reference Cohen2009, 7).Footnote 39 As this statement indicates, a defining feature of luck egalitarianism is that it holds people responsible for making sanctionable choices, where a theory holds someone responsible for a choice if and only if it reduces the size of her just share (but not others’) in virtue of that choice.Footnote 40 In other words, luck egalitarianism holds that, prior to human action, the distribution is just if and only if everyone possesses equal advantage; however, if people then make sanctionable choices, the distribution will be just if and only if each sanctionable chooser (and no non-sanctionable-chooser) ends up with a smaller share of advantage than she was originally assigned, where the size of this reduction is a function of her past sanctionable choices.Footnote 41 Of course, to give this statement of luck egalitarianism determinate content, two further specifications must be made. First, one must provide an account of which choices qualify as sanctionable. And, second, one must provide an account that specifies the extent to which any given sanctionable choice diminishes the size of the chooser’s just share.Footnote 42 Providing such a specification will be the task of Chapter 6.

To briefly illustrate the difference between strict egalitarianism and luck egalitarianism (setting aside the just-raised question of how to best specify the latter position), consider the case of two equally well-off tennis players, P and Q, each of whom owns two tennis rackets. At their weekly game, P gets very frustrated and breaks both of her rackets by throwing them against the court surface. According to strict egalitarianism, justice requires that Q transfer one of her rackets to P, as, absent such a transfer, P would end up worse off than Q due to no longer being able to play tennis. By contrast, according to practically all plausible specifications of luck egalitarianism, P’s decision to destroy her rackets qualifies as a sanctionable choice. Thus, her just share would be diminished relative to what it would have been had she not chosen sanctionably, which, in turn, implies that she would not be entitled to an equalizing transfer from Q. Further, if she were to carry out such a transfer herself by seizing one of Q’s rackets, the resulting state of affairs would be unjust according to luck egalitarianism, as P’s level of advantage would exceed her just share (while Q would end up with less than her just share of advantage due to the loss of her tennis racket).

With an account of luck egalitarianism having been provided, it is now possible to explain the anarchist’s contention that persons have distributive claims that correspond to its prescriptions. Specifically, the anarchist assigns each person a set of claims such that the luck egalitarian principle would be satisfied if all persons respected the claims of others ‒ that is, any inequality would appropriately correspond to some sanctionable choice on the part of the worse-off individuals. Or, to put this point slightly differently, each person would have a claim against anyone else using an unowned resource in some way if and only if that use would leave her with less than her appropriate share of advantage, where her appropriate share is either (a) equal to the respective shares of those who have not yet chosen sanctionably if she has also not yet chosen sanctionably or (b) adjusted downward from this value if she has chosen sanctionably (where the magnitude of this adjustment is specified in Chapter 6).Footnote 43 Thus, persons would still have rights vis-à-vis external resources, just not property rights of the kind posited by both left- and right-libertarians. Call this the anarchist conclusion.Footnote 44

To expand on the contrast between anarchist distributive claims and libertarian property rights, note that the two kinds of rights differ in the following ways. First, distributive claims are not acquired in the historical fashion that characterizes property rights, that is, they are not established via initial appropriation or subsequently acquired via transfer. Rather, moral persons start out with these rights in virtue of the fact that they possess the capacities that make them the appropriate subjects of a theory of distributive justice.Footnote 45 In other words, the world comes to persons pre-populated with resource-related exclusionary claims. This stands in contrast to the standard Lockean picture wherein all persons start out with a permission to use all things until acts of appropriation establish property claims that negate some of those permissions.

Second, distributive claims do not come bundled together in the same way that property rights do (at least, according to practically all prominent theories of private property). For example, on almost all accounts of property ownership, if one has a claim against one person using some object in some way ‒ and one has not waived or forfeited any of one’s prior claims ‒ then one also has a claim against each other person using the object in this way. Additionally, one would also have a claim against the original person (and all other persons) using the object in all other ways, that is, one would have a general claim against all others including that object in their actions irrespective of what form those actions take. By contrast, a person might have a distributive claim against one person using an object but not another person using it in an identical fashion (e.g., because only the former’s use would generate an unjust inequality). Similarly, she might have a claim against a person using the object in one way but not another. Thus, distributive claims are radically unbundled relative to property claims.

Additionally, property theorists uniformly take property claims to come bundled with various other Hohfeldian incidents such as powers to transfer and waive these claims as well as immunities from the loss of these claims. By contrast, while people can forfeit their distributive claims (as discussed in Chapters 2 and 6), they cannot waive them with respect to chosen persons. When P chooses sanctionably, she might forfeit a claim against Q using a resource in a way that disadvantages P (and advantages Q); however, P cannot simply allow Q or some other person R to use the resource, as such use might upset the just distribution. Additionally, the anarchist conclusion entails that persons lack many of the immunities from the loss of their claims that property owners possess. For example, suppose that P has a luck egalitarian distributive claim against Q using a small guest house. Given that this claim is luck egalitarian in character, it must be the case that Q’s use of the guest house would generate an inequality such that P ends up comparatively worse off relative to Q (assuming that neither P nor Q has chosen sanctionably in the past). However, suppose that an unforeseeable forest fire burns down Q’s home. Given this environmental change, it is no longer the case that Q’s use of the guest house would leave her better off than P; rather, Q would be left worse off if she did not use the guest house. Thus, P cannot retain her distributive claim against Q, as she can have a claim against some resource use only if that use would leave her with less than her appropriate share of advantage. In other words, the claims posited by the anarchist conclusion are not stable like property claims. As the guest house case demonstrates, people lack an immunity from the loss of their distributive claims, with certain unlucky events negating those claims.Footnote 46 The fact that distributive claims are unbundled from the other Hohfeldian incidents of ownership represents another significant difference between the anarchist conclusion and the theories of private property posited by libertarians (including left-libertarians).

Finally, having clarified the difference between the anarchist’s distributive claims and libertarian private property claims, it is also worth noting how the anarchist conclusion departs from standard luck egalitarianism. The key difference here is that ownership limits the domain of things whose permissible use is regulated by the distributive principle. Standard luck egalitarianism allows that the permission to use any object can be assigned to any person, that is, the right to use P’s kidney might be equally assigned to either P or Q in just the same way the permission to use an apple tree might be assigned to either person. Similarly, either P or Q might have a claim against some third party making contact with P’s body. By contrast, the anarchist conclusion maintains that if P acquires self-ownership rights over her body via an act of self-appropriation, then others cannot have distributive claims over her body. Rather, they can only have distributive claims over those things that remain unowned (with the theory adjusting these claims in response to P’s self-appropriation such that everyone discharging their correlative duties would still produce a luck egalitarian-approved distribution).

1.7 Is Anarchist Self-Ownership Too Permissive?

Now that the anarchist conclusion has been introduced, it is possible to address a potential worry about ASO, namely, that it permits bodily contact that an extensionally adequate moral theory would forbid. While ASO has many attractive implications (as discussed in Section 1.4) and independent theoretical grounding (to be discussed in Chapter 3), it also has some admittedly unattractive implications that have led philosophers to reject similar revisions of the self-ownership thesis.Footnote 47 Consider, for example, the case where a thrill seeker decides to throw glass bottles off of the top of a twenty-story building onto the street below. While she knows that some of the bottles will seriously injure pedestrians when they shatter, she derives no enjoyment from this outcome. Rather, she tosses the glass bottles strictly for the thrill of seeing them hit the ground. Given that the thrill seeker derives unique supplemental benefit from this activity ‒ assume she cannot get this same degree of satisfaction any other way ‒ it follows that she does not infringe upon their self-ownership rights according to ASO. However, critics of ASO would contend that this result is disqualifying: any acceptable account of self-ownership will entail that the thrill seeker’s bottle-throwing infringes on the pedestrians’ self-ownership rights.

This objection would be a serious problem for the ASO proponent who takes self-ownership claims to be the only claims that people have against others acting in ways that affect their bodies. Such a position would implausibly entail that the pedestrians have no claim against the thrill seeker throwing bottles at them from the rooftop. However, if one accepts the anarchist position as a whole, then one has the theoretical resources to avoid this conclusion by affirming that the pedestrians do have such a claim. Specifically, one can appeal to the anarchist conclusion presented in the previous section to point out that, when the anarchist denies the existence of property rights, she does not thereby conclude that persons are free to do whatever they like with natural resources. Rather, persons have distributive claims against others using resources in a way that would leave them worse off absent any sanctionable choice on their part. For example, if a lumberjack chopping down a tree would block a jogger’s path and thereby generate a luck-based inequality, the jogger has a distributive right against the lumberjack chopping down the tree.

By assigning people luck egalitarian distributive rights vis-à-vis objects and resources, the anarchist is able to avoid the objection that ASO entails that the pedestrians have no rights against the thrill seeker bombarding them with bottles. Contra this conclusion, the anarchist can insist that the pedestrians have distributive claims against the thrill seeker using the bottles in this way (even if they lack any self-ownership claims against her throwing the bottles). In short, proponents of ASO who take the set of claim rights to be coextensive with property rights (i.e., most natural rights libertarians) would be stuck with a highly implausible result if they endorsed ASO ‒ namely, that the thrill seeker does not infringe upon the rights of the pedestrians. By contrast, anarchists who endorse ASO merely have to maintain that the thrill seeker does not infringe upon the pedestrians’ self-ownership rights. This is a much smaller theoretical cost to bear than the extensional inadequacy of a theory that affirms that the thrill seeker does not wrong the pedestrians at all. And, given that ASO both follows from Lockean proviso (as will be argued in Chapter 3) and solves the many problems discussed in Section 1.4, it does not seem as though its potential failure to properly categorize certain wrongs warrants its rejection.