4 - “He’d Like to be Savior of the National Pastime”: Bill Clinton and the 1994–1995 Baseball Strike

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 October 2023

Summary

In February 1995, Pamela Owens, a mother from Texas who was campaigning for better educational opportunities for her autistic son, felt compelled to write to President Bill Clinton about his misplaced priorities. She had heard on the news that the president wanted to get involved in efforts to end a six-month strike in Major League Baseball (MLB) – a dispute that had led to an abrupt end to the 1994 regular season and the cancellation of the World Series for the first time in ninety years. “I would think there are a lot of more important matters to be handled by the President of the United States than the issue of baseball,” Owens wrote. Perhaps, Owens mused, she had over-valued the position of the presidency.

Pamela Owens was not alone in thinking that Clinton was misguided in his efforts over the winter months of 1994–95 to broker peace in an ill-tempered argument between 750 players and 28 owners about baseball’s labyrinthine labor practices and complex economic model. Some in Clinton’s cabinet harbored similar doubts: Vice President Al Gore feared that Clinton was being drawn into a “scorpion fight.” Labor Secretary Robert Reich recalled theories championed by the political scientist Richard Neustadt about the contingency of the persuasive powers of the presidency being “frittered away on lost causes.” The public appeared to agree: a poll circulating among White House staffers indicated that 74 percent of people were opposed to presidential intervention. Media commentators were similarly unconvinced: in the New York Times, Claire Smith wondered whether the president was “the last American willing to invest emotional energy in baseball.”

Yet despite the caution of colleagues, public suspicion, and the skepticism of much of the press, Clinton persisted in his belief that he had a role in saving professional baseball from self-destruction: he could not afford to let the national pastime die on his watch. And one of the driving forces behind his thinking was a myth that had been propagated by journalists, scholars, and politicians since the early twentieth century – that the health of the national pastime was a measure of the health and vitality of American society itself.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

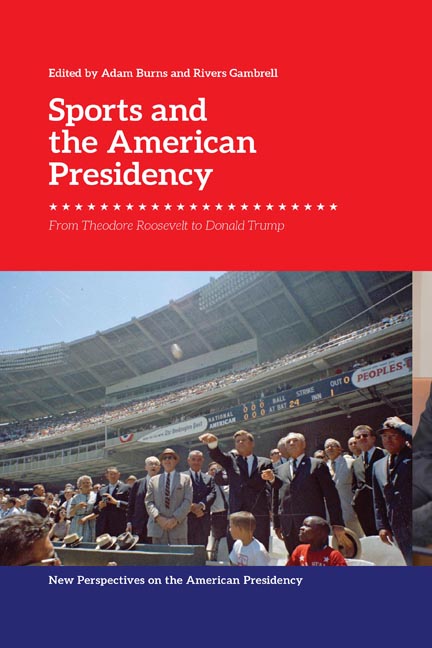

- Sports and the American PresidencyFrom Theodore Roosevelt to Donald Trump, pp. 78 - 100Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2022