Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: “What's it going to be then, eh?”: Questioning Kubrick's Clockwork

- 1 A Clockwork Orange … Ticking

- 2 The Cultural Productions of A Clockwork Orange

- 3 An Erotics of Violence: Masculinity and (Homo)Sexuality in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange

- 4 Stanley Kubrick and the Art Cinema

- 5 “A Bird of Like Rarest Spun Heavenmetal”: Music in A Clockwork Orange

- REVIEWS OF A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, 1972

- A Glossary of Nadsat

- Filmography

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

5 - “A Bird of Like Rarest Spun Heavenmetal”: Music in A Clockwork Orange

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 January 2010

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: “What's it going to be then, eh?”: Questioning Kubrick's Clockwork

- 1 A Clockwork Orange … Ticking

- 2 The Cultural Productions of A Clockwork Orange

- 3 An Erotics of Violence: Masculinity and (Homo)Sexuality in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange

- 4 Stanley Kubrick and the Art Cinema

- 5 “A Bird of Like Rarest Spun Heavenmetal”: Music in A Clockwork Orange

- REVIEWS OF A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, 1972

- A Glossary of Nadsat

- Filmography

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

INTRODUCTION: “INVISIBLE REALITIES”

Toward the beginning of Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, the young protagonist, Alex, describes an ecstatic moment in Geoffrey Plautus's one-movement Violin Concerto: “a bird of like rarest spun heavenmetal, or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now, came the violin solo above all the other strings, and those strings were like a cage of silk round my bed” (p. 39; Part 1, Chapter 3). Part of the longest sustained musical passage in the novel, it's a striking account. It's undeniably accurate, too – not because it precisely mirrors the actual score, but rather, paradoxically, because there's no actual score to mirror. For like several other pieces mentioned in the novel – both popular songs and, more important, “classical' works – the Plautus Violin Concerto has no existence in the world outside the novel.

What is the function of such references to imaginary music? Why, for instance, does Burgess use a brief phrase from Das Bettzeug, by the invented composer Friedrich Gitterfenster, to trigger the crucial fight between Alex and Dim (p. 33; Part 1, Chapter 3)? One might plausibly think that such allusions serve primarily to reinforce the futuristic aura of Burgess's invented “nadsat” language. As Burgess was acutely aware, any slang, no matter how trendy at the time a novel is written, can quickly become stale and appear outdated.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

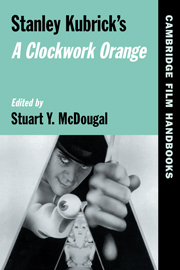

- Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange , pp. 109 - 130Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2003

References

- 3

- Cited by