‘Campaign finance and state capture’ provides a new perspective on topics that are at the heart of the literature on the political economy of development. In particular, the study of democracies in the developing world tends to focus on issues of clientelism or political exchange – directly or indirectly providing private benefits for constituencies in exchange for electoral support. However, as this chapter points out convincingly, not only are different forms of political exchange targeted at voters, different forms of political exchange are also practised by firms, each with potentially different implications for economic development and democratic consolidation. One problem with the literature on clientelism is that it tends to focus on political exchange between voters and politicians, without regard for the strategies of firms. Arguably, not only does this miss an important part of the dynamic for understanding political exchange more broadly, it also understates the developmental impact of clientelism. In focusing on small-scale ‘retail’ strategies, such as vote buying or patronage, we may be missing the more important forms of ‘wholesale’ strategies, such as capture or cooptation – strategies that arguably have more distortionary effects on both economic development and democratic consolidation.

As a result, in addition to highlighting important dynamics in Benin with implications for political institutions and economic development, this chapter addresses a first-order question in the literature on clientelism. This work is exemplary in leveraging results from a specific country context in order to make broader theoretical arguments. It does so by contributing both a novel framework – bringing together the two literatures on clientelism at the voter and firm levels – and bringing new data from Benin to test it.

I Networks

One potentially helpful area for exploring extensions to this work is to think more about firm and politician networks. Theories of networks underlie both the literature on clientelism and the literature on firm capture and cronyism, making it a natural fit given that this project is bringing new data to create a unifying framework for the two literatures. Furthermore, networks are implicit in the chapter’s analysis (even if not sufficiently explicit) and, in fact, networks were a key part of the data collection because of the snowball sampling techniques.

Networks matter not only because of the direct connections, but also for understanding the broader structure of how business interests interact with clientelism. This short note addresses two types of networks, firm networks and politician networks, in order to suggest potential extensions to the analysis. Firm networks matter because they determine access to political ‘goods’, but also because the types of networks that firms invest in may provide evidence of their priorities and strategies for lobbying. As a result, firm networks would be expected to matter for the range of demands that firms might pursue, and their techniques for doing so. It is also possible that networks operate as a constraint on firm strategies – to the extent that firms invest in developing ties and cultivating relationships with a broad range of industry and government actors, it may be difficult for them to switch strategies even when political circumstances change (Fisman, Reference Fisman2001).

Similarly, politician networks matter not only for electoral competition, but also for the types of strategies they may pursue once they are in office. For example, a large literature links politician networks to different types of electoral strategies. In particular, clientelistic political exchange requires dense, hierarchical networks for the identification of clients and the delivery of benefits and monitoring of voter behaviour. Compared to the internal organisational problems inherent in programmatic parties, for clientelist politics the problem is monitoring and controlling the political brokers at each level in the process (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007). Such mechanisms require elaborate networks to monitor actors and manage exchange relations (Stokes, Reference Stokes2005). Kitschelt and Wilkinson (Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007) describe these networks as necessary because of the need to monitor political actors at each level in the process. Research by Calvo and Murillo (Reference Calvo and Murillo2009) has argued that clientelist politics requires different types of political network structures to programmatic politics: clientelist countries have large, heterogeneous, vertically integrated parties, while programmatic countries have smaller, homogeneous, horizontally integrated parties. The ability to monitor is a fundamental aspect of successful politician networks (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Larreguy, Reference Larreguy2013).

II Firm Networks

It is widely accepted that better-connected firms exercise more political influence. However, it remains little understood how different types of ties affect different types of political action. The notion that the type of ties matters underlies much of the work on politician networks and political parties. With this type of analysis, it becomes possible to explore whether firm connections affect the strategies firms pursue, or the ways in which they engage with politicians.

For example, Cruz and Graham (Reference Cruz and Graham2021) contrast the effect of ties to other firms in the same industry (peer ties) with direct ties to elected officials and bureaucrats (government ties). Their framework proposes that peer ties facilitate collective action, most often with respect to broad policy issues that affect many firms, while government ties are primarily used to address narrow, particularistic issues. Cruz and Graham use a new survey of foreign-owned firms operating in the Philippines to demonstrate that different ties are associated with different approaches to lobbying. Consistent with theories of collective action among firms, ties to other firms are associated with efforts to influence policy at the national level, where issues are broader based and affect larger numbers of firms. By contrast, ties to government actors (bureaucrats or politicians) are associated with seeking policy influence at the local level, where actors have narrower scope but can direct specific benefits and concessions to firms.

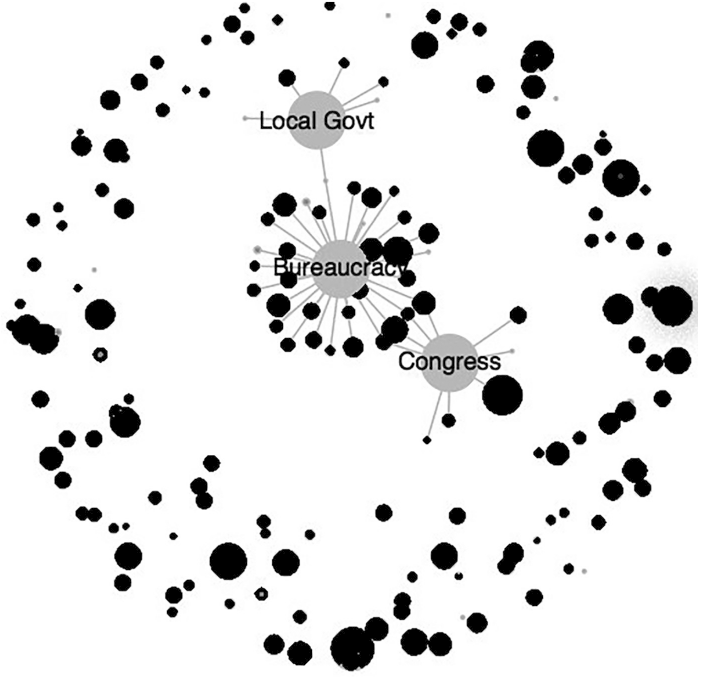

For example, Figure 4.3a is a visual illustration of firms’ ties with politicians, bureaucrats, and other firms.Footnote 14 Each of the black circles (nodes) represents an actual firm in the sample and the grey circles represent political actors: congress, local government, and the bureaucracy (labelled). For each firm, the figure presents (1) ties to congress, bureaucracies, or local government, depicted by connecting lines between the firm node and the government actor node; and (2) ties to peer firms, represented by the size of the circle, where large circles are those firms that report a larger number of peer firms. A substantial number of firms, including many with a large number of peer ties, have no direct government ties.

Figure 4.3a Peer and government ties

III Politician Networks

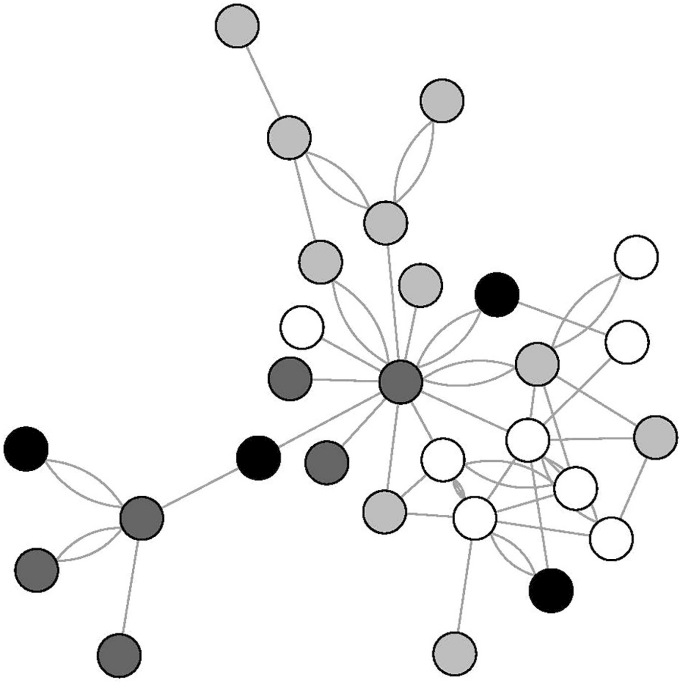

Another important aspect of networks that could extend the important findings in this chapter are differences in the networks and strategies of politicians. Figure 4.3b is a visual illustration of ties among mayors in Isabela province, in the Philippines. Some mayors are well connected horizontally, while others have vertical connections: instead of ties to other mayors, they have ties down to the village-level officials and up to the congressman (or congresswoman) and governor of the province. The structure of these ties affects the incentives of politicians to pursue different types of political exchange.

Figure 4.3b Effective mayor network in Isabela (1st district–white; 2nd–light grey; 3rd–dark grey; 4th–black)

Vertical ties are associated with individually targeted political exchange, because in a political context where there are overlapping constituencies, politicians can reduce the costs associated with individually targeted political exchange by pooling their efforts. Politicians at higher levels collude with lower-level politicians and political brokers. The higher-level politicians provide funding and the lower-level politicians provide the personnel and oversight for the implementation. A big part of the costs of vote buying involves logistics: identifying targets, sending personnel to conduct the transaction, as well as monitoring and enforcing the transaction. Once a system for monitoring or verification has been set up and the political broker has already been hired to hand out the envelope of money, the marginal cost of asking the voter to also vote for another politician on the same ballot is relatively small. The overlapping constituencies create incentives for such collusion among politicians organised through vertical networks.

Horizontal ties, by contrast, facilitate group-targeted strategies like pork-barrel politics. When pork-barrel funds take the form of spending allocated to more than one municipality, mayors who are able to cooperate with each other can act collectively to demand pork-barrel projects that benefit their municipalities. In these cases, the funding is typically controlled by politicians at the national level (such as governors or congressmen) or national government agencies. Very few local-level politicians are influential enough to lobby successfully for these types of funds on their own. However, groups of mayors acting collectively can successfully bid for large-scale projects affecting their areas. Examples of such projects include fisheries and shoreline support for coastal municipalities, irrigation systems for municipalities along a river, or construction and road projects that go through more than one locality. Horizontal ties are important not only for the process of bidding for national- or provincial-level projects, but also for ensuring that mayors cooperate throughout the project implementation process.

Extended to firms, we might also expect that the form of political alliances and political networks might also condition how politicians engage with firms. For example, politicians with ties to the bureaucracy might offer to negotiate with firms by offering regulatory deals. Politicians with more discretionary funding may prefer to offer concessions and kick-backs. As a result, in addition to considering the preferences of firms for direct or indirect forms of capture, it is equally important to consider that politicians may be differentially positioned to offer these different types of ‘policy goods’.