Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Frontispiece

- Introduction to Ten Years On The Parish

- Notes on the Text

- Autobiography from Ten Years On The Parish

- Ten Years On The Parish

- Dear Garrett: An introduction to the Garrett–Lehmann Letters

- Letters between George Garrett and John Lehmann

- Additional information

- Index

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

Dear Garrett: An introduction to the Garrett–Lehmann Letters

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

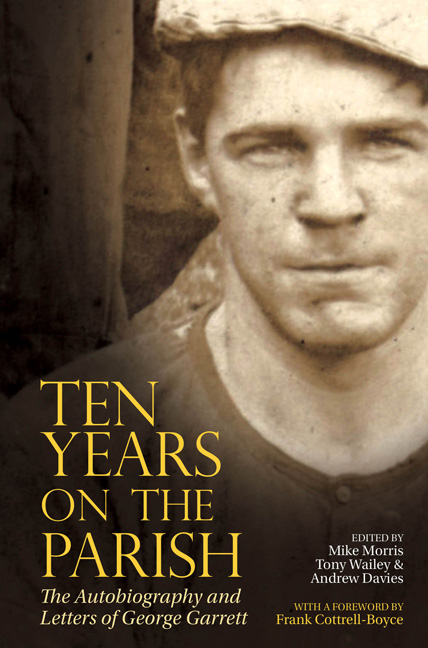

- Frontispiece

- Introduction to Ten Years On The Parish

- Notes on the Text

- Autobiography from Ten Years On The Parish

- Ten Years On The Parish

- Dear Garrett: An introduction to the Garrett–Lehmann Letters

- Letters between George Garrett and John Lehmann

- Additional information

- Index

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

Summary

The forty-eight letters exchanged between George Garrett and New Writing editor John Lehmann between January 1935 and July 1940 are a unique window into the relationship between a working-class writer and his editor, corresponding across boundaries of class and geography with the mutual aim of publishing Ten Years On The Parish.

George Garrett and John Lehmann's backgrounds could hardly have been more diverse. Garrett left his ‘slum school’ at the age of 14 and spent time ‘sleeping out’ in a stable before jumping ship, bound for Argentina and the hard life of a stoker. Lehmann was Eton and Cambridge educated, could trace his ancestry back to 1296 and ‘William de la Chambre, “Bailif e burgois de Peeble”’. Compare Garrett's early memories of mixing with children who went without shoes to that of Lehmann, who remembers being in his ‘father's library at our old family home of Fieldhead, on the Thames’ where ‘James the butler has been in to draw the blinds and curtains, and my father is reading under a green-shaded lamp’.

This introduction aims to put the letters between these two seemingly incompatible characters into context by exploring what brought them together, some of the issues highlighted within the letters themselves, and to try and reach some understanding of why Garrett left Ten Years On The Parish unfinished and, unbeknown to Lehmann at the time, moved on to new forms of writing and radical, social activities.

In 1926 the General Strike shook British society to its core. Its defeat, being called off by the Trades Union leadership after ten days, was a crushing blow to the working class. It is both symbolic and significant that Garrett's return from America should coincide with the end of the strike, when the colossal explosion of working class energy that had taken over the running of towns and cities across the country had dissipated into Garrett's lethargic description of ‘police and workers playing football together’.

John Lucas, who has himself played a crucial role in recovering Garrett as well as many other lost voices, argues that ‘the failure of the General Strike was of crucial importance to the development of radical thought and activity – including writing – and that it, rather than, say, the Wall Street Crash was decisive in shaping or conditioning attitudes both at the time and later’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ten Years on the ParishThe Autobiography and Letters of George Garrett, pp. 203 - 212Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2017