Book contents

- Time and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage

- Time and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Texts

- Introduction: The Actions and Delays of Gendered Temporalities

- Chapter 1 Virtuous Delay: The Enduring Patient Wife

- Chapter 2 Transgressive Action: The Impatient Prodigal Husband

- Chapter 3 Waiting and Taking: The Temporally Conflicted Revenger

- Chapter 4 The Delay’s the Thing: Patience, Prodigality and Revenge in Hamlet

- Conclusion: Echoes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 September 2020

- Time and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage

- Time and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Texts

- Introduction: The Actions and Delays of Gendered Temporalities

- Chapter 1 Virtuous Delay: The Enduring Patient Wife

- Chapter 2 Transgressive Action: The Impatient Prodigal Husband

- Chapter 3 Waiting and Taking: The Temporally Conflicted Revenger

- Chapter 4 The Delay’s the Thing: Patience, Prodigality and Revenge in Hamlet

- Conclusion: Echoes

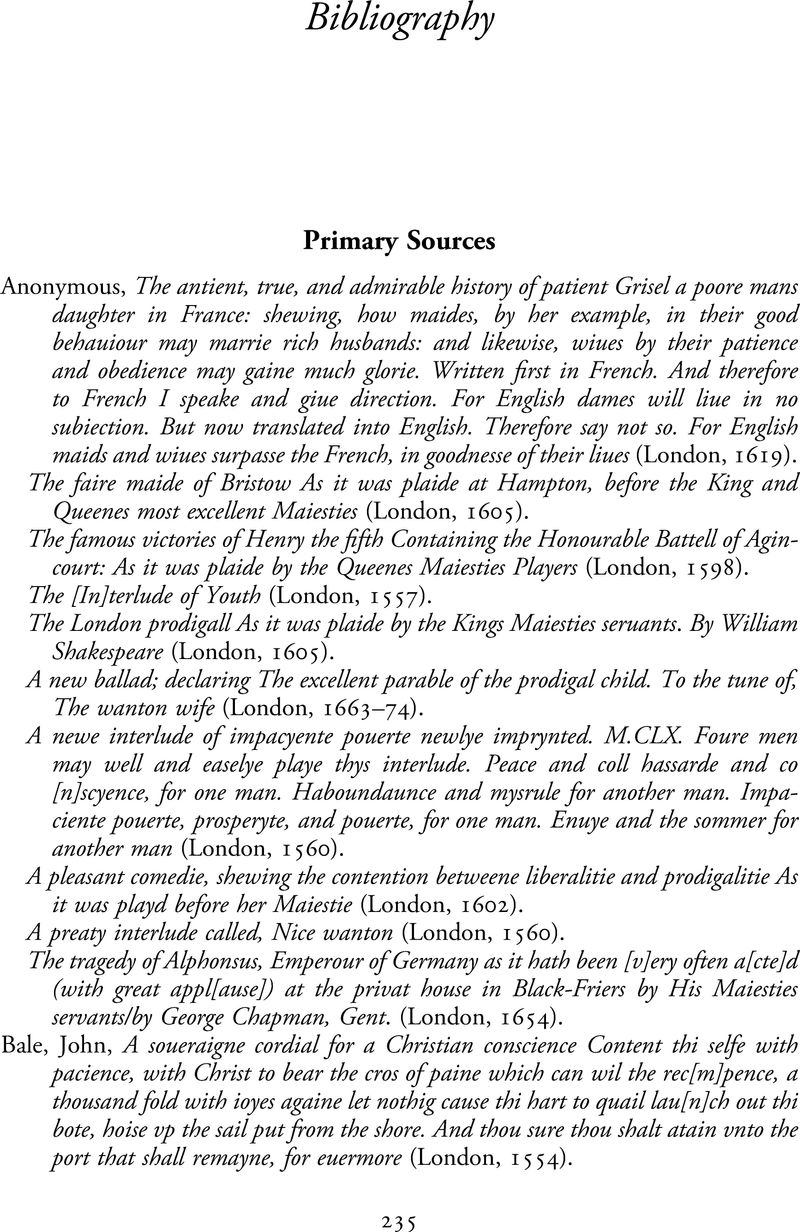

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Time and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage , pp. 235 - 270Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020