Black Saturday began on the morning of December 6, 1975, in Lebanon’s seaside capital, Beirut. After months of fighting, the city’s residents had become accustomed to violence. But they were unprepared for what came that morning. Enraged over the killing of four of their comrades, Christian militiamen had thrown up barricades along several of Beirut’s major highways. Armed men demanded that drivers produce their official identity cards, which marked individuals by religion. Many of those identified as Muslim were dragged from their cars and executed, setting off a wave of panic throughout the city. By 2 p.m., state radio declared the city streets unsafe and warned residents to remain inside. Cars careened through dangerous neighborhoods, pulling violent U-turns and dodging potentially deadly roadblocks. Meanwhile, reports of summary executions spread through the capital. Sporadic gunfire and grenade explosions echoed against the concrete and glass sides of Beirut’s high-rises. Some estimates placed the number of massacred Muslims at higher than 300. Muslim militias responded by launching an assault on three of the city’s largest hotels – the St. George, Phoenicia, and Holiday Inn – which lay under the control of Christian forces. The fighting set off a wave of sectarian cleansing punctuated by more massacres in the coming weeks as Lebanon descended deeper into a dystopia of ethno-religious warfare.Footnote 1

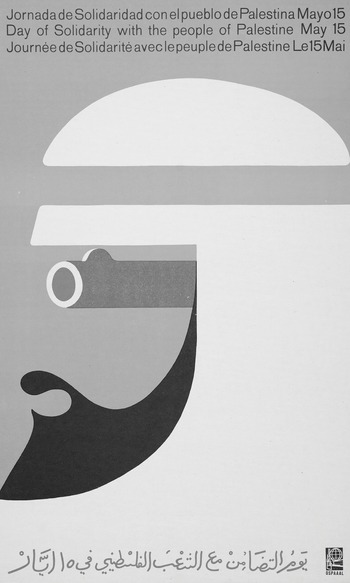

The sectarian violence raging in Lebanon confounded observers around the world. That quarreling religious communities inside a prosperous, modern state could fall into a vicious civil war flew in the face of prevailing Cold War logic. It was assumed that late twentieth-century wars were fought over political ideology, not religious faith. And 1975 should have been a banner year for the secular revolutionaries, who had long championed the vision of a Third World united in the face of world imperialism. Progressive forces around the world that supported the cause of Palestinian liberation (Figure 3.1) began the year rejoicing in the news Yasser Arafat – leader of the secular Palestine Liberation Organization – had delivered a triumphal speech on the floor of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly to thundering applause only weeks earlier. In January, North Vietnamese forces launched a military campaign that would bring them final victory in April with the Fall of Saigon. That same month, Cambodian communists seized control of Phnom Penh, creating the new socialist state of Democratic Kampuchea. In June and November, Mozambique and Angola gained independence from Portugal, driving the final nail into the coffin of the Portuguese empire and ending an era of European imperialism that had lasted some 500 years. The year 1975, then, marked the high tide of a movement of secular left-wing forces sweeping through the Third World. But even as the revolutionaries celebrated, events such as Black Saturday suggested that that revolutionary tide had begun to recede.

Figure 3.1 Support for Palestine emerged in the late 1960s as a key element of the Tricontinental movement, providing a shibboleth of revolutionary solidarity that stretched beyond the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa. In Europe and the Americas in particular, solidarity with Palestine helped differentiate the New Left from the old. OSPAAAL, Faustino Perez, 1968. Offset, 54x33 cm.

Between 1975 and 1979, secular revolutionaries around the postcolonial world suffered a series of devastating blows as an array of forces aligned against them. Geopolitical transformations in the Cold War, the increasingly acrimonious Sino-Soviet split, and the emergence of a new set of religious revolutionaries combined to slow the series of left-wing victories and open the door to a resurgence of ethnic and religious conflict around the developing world. By the end of the decade, left-wing forces found themselves embattled and the world they had sought to create in turmoil. Although this process was not confined to the Middle East, the region provided perhaps the clearest indications of the shift away from secular-progressive forms of revolutionary activity and toward ethno-sectarian models.Footnote 2 These changes were driven not only by the failures of secular postcolonial states to deliver on a range of programs but also by the deliberate policies of anti-Soviet governments in Washington, Beijing, Cairo, Islamabad, and Riyadh; the emergence of dynamic new political actors who sought to use ethnic and sectarian politics as a vehicle in their efforts to seize official power; and the disintegration of global communist solidarity. These three forces would combine to transform the face of revolutionary politics in the late Cold War and the coming twenty-first century.

Several factors have served to obscure these dynamics in traditional studies of the period. The most basic of these is the artificial scholarly separation between East Asian and West Asian history. For generations, historians in Europe and the United States have tended to cordon off East Asia from the Middle East. However, recent scholarship has begun to transcend these boundaries as global and international historians have sought to trace the connections between regions previously treated as distinct. A second factor came as the result of conventional Cold War historiography, which tended to impose an East versus West binary upon the international politics of the post-1945 era. This binary, in turn, obscured the deep fractures within the communist world, which, by the late 1970s, were in many ways even more acrimonious than the rivalry between Washington and Moscow.Footnote 3 Third, the nature of the anti-Soviet coalition between Washington, Beijing, Islamabad, Riyadh, and Cairo was largely covert. The cooperation between these regimes in theaters such as the Soviet-Afghan War was rarely well-publicized. A fourth factor in obscuring these dynamics lay in the difficulties that many US leaders had in recognizing the rising power of ethno-sectarian revolution. Mired in a Cold War mindset, officials in the Carter and Reagan administrations frequently underestimated the impact of these new forces.Footnote 4 Indeed, even Zbigniew Brzezinski’s much discussed 1978 warning of an “Arc of Crisis” focused on the threat that Soviet forces would capitalize on the upheavals in the postcolonial world rather than the threat posed by the revolutionary forces themselves: “An arc of crisis stretches along the shores of the Indian Ocean, with fragile social and political structures in a region of vital importance to us threatened with fragmentation,” Brzezinski posited. “The resulting political chaos could well be filled by elements hostile to our values and sympathetic to our adversaries.”Footnote 5 For all these reasons, the late Cold War transformation of revolutionary politics has flown under the scholarly radar. Only in the twenty-first century has it become clear that events such as the 1979 revolution in Iran were neither a communist foil nor were they some sort of aberration – rather, they helped to announce the rise of a new revolutionary politics in the postcolonial world that would eclipse the secular progressive movements of the 1960s.

The Unraveling of Cosmopolitan Revolution

No force was more disruptive to the spirit of cosmopolitan revolution than the growing rift between Moscow and Beijing. By the mid-1970s, that cleavage hit the developing world with full force. While Soviet and Chinese leaders hurled insults at one another and their troops patrolled the border along the Ussuri River, left-wing parties in the Third World were left to choose between the two communist powers. Meanwhile, China itself had emerged from the depths of the Cultural Revolution. With the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, a new faction rose to power in Beijing led by Deng Xiaoping. Deng launched a sweeping campaign of reforms that transformed the PRC’s financial system into a de facto market economy under the control of a nominally communist government. Combined with Beijing’s antagonism toward Moscow and its Cold War tilt toward Washington, these transformations shocked left-wing forces around the world, who had looked to China as a model for applying Marxist thought in Third World agrarian societies.

The second great defection of the 1970s came from Cairo. Under Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt had carried the flag of Arab revolution and had hosted the largest Soviet military deployment in the developing world. But following Egypt’s crushing defeat in the Arab-Israeli War of June 1967, Yasser Arafat and the Palestine Liberation Organization emerged as the new vanguard. Nasser’s successor, Anwar al-Sadat, was determined to change course. Nasser’s progressive, pan-Arabist policies had not delivered the desired gains at home or abroad. Egyptian economic development remained sluggish and Israel’s victory in 1967 exposed Cairo’s weakness in regional affairs. Likewise, Egypt’s failed United Arab Republic with Syria revealed the limitations of the pan-Arab experiment, while the bloody intervention in Yemen proved to be far more trouble than it was worth. If Nasser’s policies had failed, perhaps a different approach might work. Over the course of the 1970s, Sadat would begin to open Egypt’s economy to market mechanisms and Western investment, seek to reintegrate the Muslim Brotherhood into domestic politics, stage a formal break with the Soviet Union in order to partner with Washington, and forge a peace with Israel.Footnote 6

But most immediately, Sadat needed to focus on regaining Egyptian territory lost to Israel in 1967. After launching a surprise attack on Israeli military forces in the occupied Sinai in October 1973, Sadat managed to force a new round of negotiations in the Arab-Israeli peace process. In 1975, Sadat signed the Sinai Interim Agreement, which effectively returned the peninsula to Egyptian control in exchange for a de facto strategic alliance between Egypt, the United States, and Israel. For all intents and purposes, Egypt had switched sides in the Cold War, dealing yet another blow to the global cause of left-wing revolution.

Meanwhile, at the far southeastern corner of Asia, any lingering doubts about the solidarity of the global Marxist project were destroyed in 1979 when two of the most celebrated revolutionary states in East Asia – China and Vietnam – went to war against one another. Following the retreat of American forces from Saigon in 1975, tensions had grown between the erstwhile communist allies in Cambodia and Hanoi, due in part to the Cambodian regime’s suspicion of North Vietnamese regional ambitions. After years of clashes in border areas, a unified Vietnam under Le Duan – passively supported by the Soviet Union – finally invaded the country, now known as Democratic Kampuchea. China responded to the invasion of its Cambodian ally by launching its own short-lived incursion into Vietnam, plunging the region into conflict. Four of communism’s greatest twentieth-century revolutionary states – the Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, and Cambodia – had fallen into fratricidal war.

Thus, while the 1970s marked the high point of the secular revolutionary project in the global arena, they also saw that project fall into decline. Nowhere would these changes be more pronounced than in the Middle East. Between 1975 and 1982, conflicts in Lebanon, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan fundamentally transformed the geostrategic landscape of the Middle East, marginalizing secular revolutionaries and presenting new opportunities to sectarian fighters.

The Winds of Change in the Middle East

Among the earliest harbingers of this new stage of violence was the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. Lebanon sat at the intersection of many forces in the Middle East. The small republic’s confessional system aimed to integrate Christian, Sunni, Shia, and Druze minorities into a fixed sociopolitical system. The nation’s capital, Beirut, was a financial, cultural, and political gateway between the West and the Arab world. It was also a city filled with Cold Warriors: KGB, Mossad, and PLO agents prowled its streets, and the US embassy and CIA stations were among the largest in the Middle East. That this city of modern high-rises and luxury hotels could become a battleground filled with sectarian militias who massacred thousands of civilians hinted at the massive changes underway.

Three years later, one of the greatest bastions of American power in the Middle East began to collapse. The sharp rise in the price of petroleum over the 1970s dramatically expanded the influence of conservative, oil-rich states with expanding ties to the United States, most notably Saudi Arabia and Iran. Gone was the Nasserite progressive vision of a secular, anti-colonial Arabic world strategically positioned between the Cold War superpowers. While Riyadh launched sweeping initiatives to set up Islamic charities and Wahhabi-influenced madrasas throughout the region, Tehran worked to modernize its military forces, buying up state-of-the-art military equipment from the United States as a way of solidifying both domestic stability and regional influence. But the flood in petrodollars sparked sharp inflation in the Iranian economy that combined with festering resentments against the Shah’s repressive state to unleash a mounting rebellion in Iran. Over the course of 1978 and 1979, increasing numbers of Iranians took to the streets in protest against the Shah. Though the revolution initially comprised a broad base of Iranians, religious clerics and their followers soon began pushing aside secular left-wing groups with the unintentional assistance of the Shah. Spearheaded by the SAVAK – a massive secret police organization trained by the American CIA and the Israeli Mossad – official repression eliminated all bases of power outside the region save the top religious establishment. Once the Shah’s hold on power began to slip, Iran’s Shia clergy represented the most organized force in Iranian society. The exiled cleric Ayatollah Khomeini, long a violent critic of the regime, emerged as the voice of this movement by defining an Islamic internationalism that rejected both Western capitalism and Soviet Communism as equally corrupt, dangerous, and morally bankrupt. The revolution’s theocratic turn shocked outside observers who had become accustomed to see Marxist thought rather than religious faith as the hallmark of the twentieth-century revolutionary. The Shah fled the country in January 1979, paving the way for the Ayatollah Khomeini’s triumphal return in February, and removing one of Washington’s staunchest allies in the region.Footnote 7

Although the drama in Tehran marked the clearest indication that the locus of revolutionary power had shifted from secular radicals to religious leaders, it was far from the only one. The Sunni world fostered its own cadre of religious revolutionaries as well. In November 1979, a group of religious extremists anticipating the end of days seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Over the next two weeks, the rebels fought off a series of ferocious assaults by government forces. When the smoke cleared, nearly 300 pilgrims, soldiers, and rebels lay dead. The following January, Saudi officials beheaded 63 of the captured insurgents in public squares across the country. But the larger impact was to lead the Saudi government to grant greater power to religious authorities and to tighten religious restrictions throughout the country. Riyadh managed to maintain control of the state and continue its drift toward an American alliance that many revolutionaries deemed unacceptable by canalizing and co-opting the religious fervor that was overtaking the region.

Such revolution was not limited to American allies. Three weeks after Saudi forces regained control of the Grand Mosque, the Soviet Union launched a massive military intervention in Afghanistan to defend the Marxist regime in Kabul against Islamic rebels. Although officials in Washington worried that the intervention was the first step in a larger offensive aimed at the Persian Gulf, the Soviet move was driven by deep anxieties in Moscow. Soviet leaders worried that Kabul might choose to align with the United States and thus transform Afghanistan into a base for American missiles along the Soviet Union’s southern frontier. Others in the Kremlin worried that the Islamic revolution in neighboring Iran coupled with the rise in Islamic militancy in Afghanistan could spill across the border, infecting the millions of Muslims living inside the Soviet Central Asian republics. Fueled by these concerns, a reluctant Soviet leadership chose to send their forces into Afghanistan to save the failing regime in Kabul.Footnote 8 In a war that lasted more than nine years, Soviet troops battled Afghan guerrillas across thousands of miles of rugged territory.

Throughout the conflict, US, Pakistani, and Saudi intelligence services shipped large stores of weapons to the Afghan rebels. Pakistani agents ensured that the largest shipments went to Islamic fundamentalist groups aligned with Islamabad. The ideological and religious connotations of the struggle against infidel invaders from the Soviet Union – which had long suppressed its Muslim minorities and discouraged religious practice – contributed to the evolution of a revolutionary Islamic solidarity. Prioritizing Cold War security interests over its unease with radical Islamists, US and Saudi agents helped establish a network of volunteers in the Arab world, many of whom journeyed to Afghanistan to participate in the jihad. By the end of the war, pro-Pakistani religious warriors supported by radical Arab volunteers commanded the most formidable rebel forces inside Afghanistan. In this way, the Soviet-Afghan War became the fountainhead for what would become a globalized jihadist movement in the closing years of the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first century.

The year 1979 marked a pivotal conjuncture in Middle Eastern political history. Though direct linkages between the Camp David Accords, the Grand Mosque siege, the Iranian Revolution, and the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan remain largely elusive, historians now recognize the end of the 1970s as a watershed in the region.Footnote 9 From a global perspective, 1979 represented an even larger shift. For the next decade, brutal wars raged in Afghanistan, Lebanon, and along the Iran-Iraq border. While East Asia had been the deadliest region in the preceding three decades, the Greater Middle East became the most violent part of the world after 1979. Thus, this critical juncture at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s witnessed the convergence of three, global historical transformations. The Greater Middle East became the most violent region in the world, the path of postcolonial revolution turned away from Marxism and toward ethno-religious avenues, and the Cold War came to an end. This was no coincidence. Rather, the same forces that led to the end of the contest between the United States and the Soviet Union brought war to battlefields across the Middle East and paved the way for the onset of a new set of revolutionary dislocations in the postcolonial world.Footnote 10

The developments in the Middle East in the 1970s and 1980s helped transform the Third World revolutionary project from one focused on Marxism to one increasingly focused on ethnic and religious identity. It is worth noting, moreover, that this process cut across religious groups. Christian forces in Lebanon; Iranian Shia; Saudi, Pakistani, and Afghan Sunnis; and Jewish radicals in Israel all answered the call of holy war. The transnational nature of these changes and their occurrence at the same time as major transformations in the Cold War international system defies purely local explanations.

The Palestinian Bellwether

The PLO’s case maps neatly onto these transitions. The PLO emerged, in its authentically Palestinian form, out of the zeitgeist of the global 1960s. Like many in the Arab world, Palestinian leaders had looked to Nasser and Pan-Arabism in the decade between 1956 and 1966. Arab unity and state-based development under the leadership of the most powerful government in the Arab world appeared as the most promising means of national salvation. The PLO itself was created by the Egyptian government in 1964 in a bid to bind the power of Palestinian nationalism to Nasser’s regime. But the humiliation of the 1967 war crushed the allure of pan-Arabism and opened the door for new leaders such as Yasir Arafat and George Habash who would wrest control of the Palestinian nationalist movement from Egypt in the months after the 1967 war.Footnote 11

While Cairo had been humbled, the exploits of another revolutionary capital enthralled the postcolonial world. Waging a desperate liberation war against the greatest superpower on earth, Hanoi and its legions of soldiers and guerrilla fighters were in the process of pulling off the greatest military upset of the Cold War. In January 1968, Vietnamese communist fighters launched the Tet Offensive, which would come to be seen as the decisive turning point in America’s Vietnam War. Though their ranks were devastated, the Vietnamese guerrillas achieved a political and psychological victory that reverberated across the globe. Two months later, Palestinian guerrillas snatched their own victory from the jaws of military defeat at the Battle of al-Karamah in Jordan. There, Arafat’s Fatah chose to stand and fight against a superior column of Israeli forces. Arafat’s men suffered heavy casualties, but their actions provided grist for Fatah’s propaganda mills. In the following weeks, a flood of volunteers rushed to join the Palestinian liberation movement and Arafat emerged as the new face of the revolution in the Middle East.Footnote 12

Electrified by the myth of the heroic national liberation fighter, Palestinian cadres heralded Chinese, Vietnamese, Cuban, and Algerian guerrillas as comrades in what Yasir Arafat dubbed “the struggle against oppression everywhere.” Palestinian groups used the teachings of Mao and Che Guevara and the lessons of the Algerian war to devise their own set of tactics in their liberation war against Israel. PLO leaders also devised a new set of international strategies targeting international transportation networks and global organizations that they, and others, understood to be a significant contribution to the playbook on revolutionary war.Footnote 13

Although Islamic revolutionaries would adopt the group’s strategies in the 1980s, the PLO remained ardently secular. Clothed in the guise of Third World liberation warriors, Palestinian fighters achieved startling gains in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This was the heyday of the secular Third World guerrilla. Havana’s Tricontinentalism, Algiers’ status as the Mecca of revolution, and Hanoi’s fight on the frontlines against neo-imperialism – not to mention the animated youth movements in the United States and Western Europe – all fueled the sense that a worldwide revolution was underway. For these groups, secular liberation appeared as the most viable vehicle for achieving revolutionary success. Third World solidarity paid impressive dividends to the PLO. Riding a wave of popular support in forums such as the United Nations and the Conference of Non-Aligned States, PLO representatives swept onto the international stage in 1973 and 1974. Arafat’s dramatic address to the UN General Assembly in late 1974 marked the culmination of this global diplomatic offensive. In the space of seven years, the PLO had managed to gain international recognition as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, to return the Palestine question to the center of the world stage, and to establish itself as a seemingly permanent fixture in the politics of the Arab-Israeli dispute.Footnote 14

But 1975 marked a troubling turning point for these revolutionary forces as well as for the PLO. The start of the Lebanese Civil War, which witnessed an attack on a busload of Palestinians by Christian militiamen, heralded the dawn of a challenging new era for the organization. Palestinian leaders initially tried to stay out of these internal clashes. Although the presence of the PLO in Lebanon had played a key role in pushing the nation over the brink into civil war, the PLO recognized that a messy war against Lebanese militias would merely drain energy and resources from the real struggle against Israel. But despite their efforts, the Palestinians found themselves pulled into the fray. As the war dragged on, the PLO was forced to commit forces to fighting fellow Arabs in defense of refugee camps in Beirut. In short order, the camps became fortified bases in a war marked by ethnic and religious massacres.

Although the war’s initial alignments broke down roughly into a struggle between left-wing Muslim and Druze forces and conservative Christian militias, a string of victories by the PLO and its allies in late 1975 and early 1976 prompted a Syrian intervention to restore the status quo. Hafiz al-Assad’s regime in Damascus feared that a PLO victory would destabilize Lebanon – a development that would dramatically compromise Syrian security – and recognized an opportunity to expand Syria’s influence in the Levant. Coupled with Sadat’s defection after the 1973 war, Assad’s intervention against the PLO and its left-wing allies in Lebanon dealt yet another blow to any hopes of progressive Arab solidarity.Footnote 15

Likewise, the Sino-Soviet split and the Sino-Vietnamese War complicated the situation in the Middle East just as the 1979 Egypt-Israeli Peace Treaty was being finalized. In the years following Sadat’s 1972 expulsion of Soviet advisors from Egypt, relations between Cairo and Beijing had improved. Chinese leaders had picked up some of the Kremlin’s commitments as an important outside supporter of the regime in Cairo. Beijing recognized the Middle East as an arena in its rivalry with Moscow. As such, Chinese leaders worried about any potential Soviet moves in the region, a stance that ultimately undermined the cause of secular left-wing revolutionary activity in the Arab-Israeli conflict. As Chinese Foreign Minister Huang Hua argued in April 1979, the “main foe of Arab unity and peace in the Middle East was not Israel but the Soviet Union.”Footnote 16 Beijing thus recognized the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty as a potential wedge against Moscow’s influence in the Middle East. Nevertheless, the Arab opposition to the treaty and Sadat’s increased isolation in the region created a precarious situation for Beijing.

Furthermore, Chinese leaders had no intention of letting their support for the PLO complicate their relationship with Egypt and their larger goal of diminishing Moscow’s role in the region. Warmer relations between the PLO and the Kremlin served to further diminish Beijing’s sympathies for the Palestinians. The result, British officials noted in 1979, “has naturally led the Chinese to pull their punches in support of the PLO.”Footnote 17 The public support from some PLO members for Vietnam during the Sino-Vietnamese War represented yet another blow to relations between Beijing and Palestinian leaders.Footnote 18

The New Face of Revolution

Thus, by the early 1980s, the glory days of revolution seemed very far away. The 1982 Israeli invasion, which aimed to reinstall a pro-Western Christian government in Beirut and eradicate the PLO, marked a climax to the civil war in Lebanon. Palestinian fighters found themselves besieged in Beirut, dodging Israeli artillery shells along with the city’s civilian population. The agreements that ended the siege forced the PLO’s evacuation to Tunisia, some 1,500 miles from Palestine. Removed from the frontlines of the struggle against Israel, the organization fell into crisis. The horrific massacres of Palestinian civilians at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps by Christian militiamen under the protection of Israeli soldiers followed. So too did the US intervention in Lebanon and the Marine Barracks Bombing by the Shia guerrilla group Islamic Jihad. The PLO’s expulsion from Beirut did little to quell the tides of war in Lebanon. If the first half of the civil war had revolved around the PLO’s presence, the second half would focus largely on the rise of the Lebanese Shia, and Hezbollah. The PLO’s exit in 1982 served as a fitting symbol for the decline of the secular revolutionary and the rise of ethno-religious violence in the developing world.Footnote 19

The PLO’s evacuation to the shores of the western Mediterranean removed the leading force in secular Palestinian politics from the primary theater of the Israel-Palestine struggle. But Arafat’s banishment did nothing to quash the grassroots force of Palestinian nationalism. As the Israeli occupation dragged on, the frustration of ordinary Palestinians broke out in a popular uprising in 1987. The so-called Intifada caught Arafat and the PLO off guard. Here were everyday Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza rising up in their own, predominately non-violent protest against the Israeli authorities. While Arafat scrambled to reassert leadership over the uprising, factions within the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood inside the Occupied Territories formed a new resistance organization, Hamas, which eschewed the PLO’s secular ideology at the same time as it embraced the organization’s tactics of guerrilla war. Finding the path to secular liberation blocked, many of the Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza were ready to embrace this new political movement and its promise of Islamic liberation. In the coming decades, Hamas would emerge as a powerful challenger to the mantle of Palestinian leadership.Footnote 20

Conclusion

The PLO’s case thus serves as a microcosm of the complex set of changes taking place during the late Cold War centered on the demise of the secular liberation movement typified by the participants of the Tricontinental movement and the rise of a trend toward ethnic and religious violence. This transition was not purely a product of a resurgence of local traditionalism and fundamentalism. Rather, this phenomenon was born at the intersection of local dynamics and global changes taking place across the Cold War world. The East-West struggle led both Washington and Moscow to bankroll a system of highly militarized states around the developing world. These states relied on foreign aid and bloated militaries rather than popular support.

Meanwhile, Washington’s containment strategies, which included everything from financial and military aid to right-wing states to covert operations and full-scale military interventions, crippled secular revolutionary movements around the Third World. Likewise, right-wing regimes in Africa, Asia, Latin American, and the Middle East built their own networks aimed at combating the tide of left-wing movements around the world. Just as damaging, however, was the unraveling of global communist solidarity with the Sino-Soviet split and the Sino-Vietnamese War. Although the Third World aid networks linking PLO fighters to Hanoi, Beijing, Algiers, and Havana had been broad, they were seldom deep. The most common form of assistance came in the symbolic realm. Postcolonial revolutionaries could employ Mao’s writings or the Vietnamese example to mobilize their own cadres and explain their struggle to the wider world. These efforts generated wide support among progressive forces around the globe. More often than not, these symbolic identifications led to diplomatic support from revolutionary states in international forums such as the UN General Assembly and the Conference of Non-Aligned States. But by the 1970s, the value of such rhetorical support was on the decline. The Sino-Soviet split and the Third Indochina War gutted the symbolic allure and diplomatic weight of Third World communist solidarity.

Furthermore, neither symbolic identification nor diplomatic support typically demanded significant resources. Rhetoric rarely translated to extensive material aid and could not make up for the loss of the concrete assistance provided by more invested local actors if they – like Egypt – switched political courses. Once revolutionary states such as China, Vietnam, and Algeria were called upon to put their money where their mouths were, so to speak, dynamics changed. Indeed, financial and military aid networks among revolutionary states and movements were not nearly as extensive as symbolic and diplomatic connections. Beijing and Algeria operated a number of guerrilla training camps in the 1960s, which served as important nodes in these global revolutionary networks. The PLO would set up their own camps in the 1970s where they famously hosted members of the German Baader–Meinhof Gang among others. But by the 1980s, the world’s largest complex of guerrilla training camps was being funded by the US and Saudi governments in Pakistan. These camps focused not on training secular left-wing revolutionaries but on building legions of anti-Soviet Mujahideen, many of whom were inspired by calls to holy war. A similar story emerges when one turns to look at military aid. The PRC had served as an important patron of revolutionary movements in the 1950s and 1960s, as the ubiquity of Chinese-made Kalashnikovs among postcolonial liberation fighters indicated. And these small arms were potent weapons in the hands of the committed guerrilla revolutionaries of the long 1960s. But over the 1970s, as China and the United States achieved rapprochement, Chinese leaders focused their energies elsewhere. By the 1980s, Beijing, Washington, Islamabad, and Riyadh were directing large numbers of weapons into the hands of the Afghan Mujahideen.Footnote 21

It could also be argued that Third World revolutionary solidarity became, in some sense, a victim of its own success. Once in power, victorious revolutionaries in Havana, Beijing, Hanoi, Algiers, and Phnom Penh, among other capitals, faced the challenge of building new governments. The burdens of governance often quenched the fires of revolution as they transformed guerrillas into bureaucrats. In this way, after achieving success, many revolutionary governments recognized that their interests diverged from their former revolutionary comrades. Beijing’s recognition in the mid-to-late 1960s that Moscow – not Washington – represented the greatest threat to Chinese national security serves as a key example of this dynamic.Footnote 22

Thus, by the end of the 1970s, the always slapdash alliance of postcolonial revolutionary forces had lost much of its symbolic luster, been deprived of some of its key state sponsors, and been outclassed by the new US-Saudi-Pakistani syndicate that was intent on mounting a jihad against the Soviet Army in Afghanistan. Khomeini’s triumph in Tehran may have driven the final nail into the coffin of Third World revolutionary solidarity as a dynamic force in world affairs. Not only did the forces of sectarian revolution appear more energized, but their patrons proved more generous than their secular counterparts. In this way, Washington and Riyadh provided the largest financial contributions to revolutionary forces in the 1980s under the auspices of its clandestine aid program to the Mujahideen.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the revolutionary forces of the late Cold War increasingly turned away from secular visions of liberation and toward ethnic and religious ideologies. But as the Afghan, Lebanese, Iranian, Iraqi, and Palestinian cases show, these ostensibly local transformations were fueled by infusions of aid from the superpowers and by transnational flows of ideas and soldiers. Thus, though they were born from local circumstances, these changes were firmly embedded in the global currents of the Cold War international system. It was no coincidence, then, that the resurgence of ethno-religious warfare in the Middle East and the wider Third World took place on the heels of the Sino-Soviet split, the Sino-Vietnamese War, Egypt’s break with the Soviet Union, and the Deng Xiaoping’s rise to power. By 1979, Moscow was fighting a bloody intervention in postcolonial Afghanistan; Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Chinese soldiers were in open war with one another; Beijing was leaning toward Washington and beginning a series of market reforms; and Egypt had forged a de facto alliance with Israel and the United States. The unraveling of the Third World communist project foreshadowed the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet state. The rise of ethno-religious conflict in the Middle East must ultimately be understood as a crucial dimension of the story of the end of the Cold War. Likewise, the end of the Cold War and the demise of the global communist bloc should be seen as a crucial component of the resurgence of ethno-religious conflict in the Middle East and elsewhere.