A near cloudless morning greeted Abdulrahim Farah as he stepped onto the tarmac of the Lusaka International airport on August 17, 1969. The fifty-year-old Somali diplomat was only months into his tenure as the chairman of the UN Special Committee on Apartheid. He had left New York in the midst of an intense summer heat wave and the city behind him – like most of America in 1969 – was simmering with tension. Surrounded now by an entourage of UN diplomats, Farah probably relished the change of scenery. Zambian soil must have been a welcome reprieve from his life as an expatriate in urban America.Footnote 1

However, turmoil was hard to escape in 1969. The Apartheid Committee Farah presided over had been established at the height of the so-called postcolonial moment, shorthand for the period when decolonization changed Africa’s political map between 1957 and 1963. The Committee had been the centerpiece of a set of initiatives that sought to use the United Nations to end white supremacy in Southern Africa, but those heady days were gone. Farah had journeyed to Zambia because he hoped to reach out to the liberation movements living there, many of which questioned the UN’s usefulness in the anti-apartheid fight, and to repair the bonds that once linked African people through Pan-Africanism.

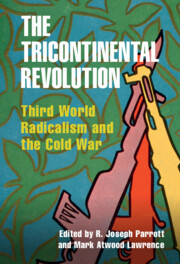

Figure 5.1 Tricontinental movements won support by combining political and social revolution, which often promoted the liberation of women alongside national independence. This image also attests to the global movement of iconography via Tricontinental networks. The Cuban artist Lazaro Abreu adapted this poster from an Emory Douglas illustration in The Black Panther depicting African revolutions. The combination of woman, gun, and baby appeared in Asian and African revolutionary imagery, which proved popular with young leftists in Europe and the United States. Lazaro Abreu after original by Emory Douglas, 1968. Screen print, 52x33 cm.

Things did not go well. During the Committee’s initial round of discussions, the African National Congress (ANC) requested that Farah and his associates stop seeking publicity for themselves and “humbly suggest[ed]” that these self-serving vacations had outlived their utility. “In our view it would be less expensive … if the United Nations invited, at its expense, delegations from genuine liberation movements to attend meetings … and assist in discussions and decisions.” Heralded once as the anvil that would destroy apartheid, the United Nations – and specifically the Apartheid Committee – was now portrayed as useless. In another meeting, an activist argued that “concrete evidence” proved that the United Nations was “a tool of the imperialist powers, particularly the United States,” while a third freedom fighter said that the “time for the verbal, the constitutional, was passed.” The only way forward now “was to face the enemy with a gun.”Footnote 2

Members of Farah’s party were taken aback. They saw themselves at the vanguard of the revolution against racial discrimination, and they were being told they were part of the problem. A few UN delegates accused the activists of being ignorant about “the workings of the United Nations.” However, Farah responded to the criticism directly. If the ANC wanted violence, it had to recognize that “nobody would pay any attention” until its members were “killed and maimed.” Ultimately, repudiating the Apartheid Committee was an act of self-isolation. Unless there “were more Sharpevilles” – a reference to a massacre outside Johannesburg in 1960 – “there would be indifference.”Footnote 3

What explains the hostility Farah faced in 1969? Arguably, the anti-apartheid movement was the most prominent social cause of the twentieth century; it lasted decades and drew support from people in the Americas, Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa. But Farah’s experience reminds us that apartheid’s critics quarreled often and with considerable fervor. The anti-apartheid movement’s resilience, and eventually its ubiquity, stemmed from this fractiousness. Farah and the ANC disagreed about tactics, specifically the utility of special committees, and they articulated opposing conclusions about the United Nations’ usefulness in the worldwide decolonization movement. But both sides wanted legitimacy, and their boisterous fight, while not a zero-sum contest, made the apartheid issue harder to ignore during the second half of the twentieth century. Even as apartheid’s critics unanimously blasted the vagaries of white minority rule, they maneuvered among the subtle differences between solidarity and self-interest.

Historians of South Africa have largely ignored this tension. Astute monographs by Gail Gerhart and Tom Lodge consider rifts among anti-apartheid activists, but their books focus on black power and racial pluralism.Footnote 4 Although Stephen Ellis and Paul Landau offer an alternative framework, their work overdramatizes Moscow’s control of the ANC.Footnote 5 Hilda Berstein, Hugh Macmillan, and Scott Couper provide soberer accounts, lingering on the disagreements between the ANC’s various headquarters and the generational differences among its leaders, and Arianna Lissoni and Saul Dubow illuminate the way multiracialism and non-racialism contributed to the ANC’s factionalism.Footnote 6 Rob Skinner and Simon Stevens have even considered the ANC’s relationship with international anti-apartheid organizations.Footnote 7 But the national project of South Africa has framed all of this literature, and most of these authors have probed the liberation struggle in order to historicize the country’s turmoil in the twenty-first century.Footnote 8

Farah’s journey provides a different sort of starting point. While past scholars have tended to attribute splits within the liberation struggle to South Africa’s internal divisions, this chapter flips that approach inside-out, arguing that external events shaped the organization’s self-understanding. At the heart of the chapter is an obvious yet underexplored paradox. Forced into exile in 1960, the ANC’s underground paramilitary wing, uMkhonto weSizwe, was defeated in 1963. This defeat effectively ended the organization’s footprint within South Africa until the 1990s. Although ANC leaders continued to present themselves as spokesmen for an authentic, anti-racist South African nation – and stayed informed about events at home – the ANC existed primarily as a diasporic entity after the mid-1960s and many of its established truths lost the power to motivate the masses in these years. How could an organization that suffered so many setbacks maintain its place at the forefront of the anti-apartheid movement?

This chapter’s argument is straightforward: analogies matter. It studies the ANC’s road to and from the 1966 Tricontinental Conference and draws upon research from the ANC’s Liberation Archive to suggest that external comparisons – not internal divisions – determined how the ANC explained what it stood for and what it wanted after the Sharpeville Massacre. Critically, these analogies changed over time. During the early 1960s, the ANC equated itself to the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), which historian Jeffrey James Byrne critiques in Chapter 6. Initially, ANC leaders believed they could leverage diplomatic victories to defy minority white rule in South Africa. When the Algerian analogy faltered in the mid-1960s, the Cuban revolution became an alternative model for South Africa’s future. Fidel Castro’s apparent strength contrasted with the fate of Algeria’s Ben Bella (and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah), suggesting that real freedom required guerrilla warfare, not UN General Assembly resolutions. However, the ANC’s embrace of Che Guevara’s ideas set off a regional crisis that upended the organization in 1967, leading to the chapter’s final section on Vietnam. Divided internally by the late 1960s, the ANC responded to the Vietnam War by probing the logic and purpose of Third World solidarity, which offers a useful window to explore the relationship between revolutionary talk and revolutionary action after the Tricontinental Conference.

These shifting analogies served the ANC well. They helped the organization establish alliances with foreigners who never experienced apartheid, and they assuaged ANC expatriates who feared that Europeans would always rule South Africa. But most importantly, for the purposes of this book, the ANC’s efforts provide a microcosm to consider how the Tricontinental Revolution changed the Third World project. By studying the context around Farah’s rancorous encounter with the ANC in 1969, we can explain the tension between solidarity and revolution. After all, solidarity is what Farah was looking for in Lusaka. Yet he failed to obtain it because he was not a revolutionary. This chapter scratches at this tension while exploring how ANC leaders tangled with one of this volume’s organizing questions: Was Tricontinental solidarity an end in itself or was it a means to foment violent change in the decolonized world?

Exceptionalism

As late as 1960, ANC leaders refused to compare themselves to foreigners. Because apartheid differed from European imperialism, the argument went, the ANC’s struggle for majority rule had to be explained in the context of South Africa’s past. The ANC’s exceptionalism rested on a particular interpretation of history. An earlier rebellion against colonialism, fought in the late nineteenth century, pitted Dutch and British settlers against each other, and the forced migration of South Asians to the region significantly complicated the machinations of colonialism there. South Africa fit no mold, the argument went, and apartheid, which took shape after Afrikaner nationalists won power in 1948, elaborated British racism by repudiating Anglo-American liberalism, putting the country at odds with the rest of the English-speaking world after World War II. While apartheid’s critics took inspiration from Indian independence in 1947, the ANC’s 1952 Defiance Campaign, which imported Gandhian methods of civil disobedience to South Africa, neither changed government policy nor united the country’s various ethnic groups under a common banner. By the mid-1950s, it appeared that South Africa was sui generis.Footnote 9

This mindset created a distinct framework for political dissent. In South Asia, Jawaharlal Nehru spoke of a coherent Indian personality, channeled through the Indian National Congress. In South Africa, by contrast, the Congress Alliance, established after the Defiance Campaign’s defeat, argued that heterogeneity had to be the wellspring of anti-apartheid politics.Footnote 10 Within the Congress Alliance, the African National Congress spoke for indigenous Africans, while the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions, the Coloured People’s Congress, and the Congress of Democrats represented other anti-apartheid groups. The birth of this alliance went hand in hand with a Freedom Charter in 1955 that framed South Africa as a place that “belonged to all who live in it, black and white,” accentuating the premise that South Africa would not follow the same path as India after 1947.Footnote 11 Rather than creating a racially homogeneous anti-colonial nation-state, the ANC would forge a politically plural and ethnically diverse democracy. If the Freedom Charter had an audience outside the country, it was probably the United Nations, a heterogenous organization invented to combat fascism, which had authored similar statements about politics after 1945. The Freedom Charter equated apartheid with fascism while dramatizing the difference between South Africa’s near future and South Asia’s recent past.

This approach began to buckle in the late 1950s. While the Congress Alliance struggled to gain traction within South Africa, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah used Nehru’s vision to spearhead the first successful anti-colonial movement in Sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 12 After winning independence from Britain in 1957, Nkrumah called an All-African People’s Conference in 1958, proclaiming the need for a continent-wide “African Personality based on the philosophy of Pan-African Socialism.” Convinced that such a move would end the Congress Alliance, the ANC responded defensively. To comprehend “our aims and objectives,” ANC representatives informed Nkrumah and his supporters, outsiders needed to recognize South Africa’s “political, economic, and social development,” especially the fact that it was “the only country in Africa with a very large settled White population.” Because of “this history,” the statement continued, “our philosophy of struggle is ‘a democratic South Africa’ embracing all, regardless of colour or race who pay undivided allegiance to South Africa and mother Africa.” Although the ANC “support[ed] the cause of National Liberation,” it pointedly refused to adopt Nkrumah’s political vocabulary. The ANC faced a problem called “national oppression” – not foreign imperialism – and the remedy was not decolonization but “universal adult suffrage” within a democracy based on the Freedom Charter.Footnote 13 This argument not only undercut Nkrumah’s call for an all-encompassing African nationalism – modeled on Nehru’s Indian nationalism – but also reified the premise that South Africa was in but not of the African continent.

The ANC’s exceptionalism crumbled spectacularly after the All-African People’s Conference. Just a few months later, Robert Sobukwe, a former ANC Youth League leader who left the organization in the late 1950s, answered Nkrumah’s clarion call by organizing a new group called the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).Footnote 14 The organization announced its existence in 1959 and immediately attacked the ANC’s multiracialism as a “method of safeguarding white interests.” The ANC conceptualized South Africa’s future on Europe’s terms, Sobukwe argued, and failed to recognize the continuities between settler colonialism in South Africa and imperialism everywhere else. Part of the problem, in his mind, was the ANC’s relationship with the South African Communist Party (SACP), whose members seemed to take inspiration from European communists.Footnote 15 Because “South Africa [was] an integral part of the indivisible whole that is Afrika,” Sobukwe wrote in 1959, it followed that political power had to be “of the Africans, by the Africans, for the Africans.”Footnote 16 As the PAC cast the Freedom Charter aside, it attacked the presupposition that universal suffrage would end national oppression, proclaiming that a truly independent South Africa would have to belong to the “Africanist Socialist democratic order” that would soon stretch from Cape Town to Cairo. Decolonization was not only in South Africa’s future; it would arrive before 1963, Sobukwe declared in 1960. That was Nkrumah’s target date for African liberation and Pan-African unification.Footnote 17

The ANC lost control of events in early 1960. When British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan visited South Africa in February, he too attacked South African exceptionalism, albeit to critique apartheid’s architects for failing to acknowledge the “national consciousness” of non-Europeans.Footnote 18 Intended to sting Afrikaners who opposed the “winds of change,” Macmillan’s barb also challenged the ANC’s beleaguered worldview by conflating anti-apartheid activism with the movement that had recently ended British rule in Ghana. The Sharpeville Massacre, which featured so prominently in Farah’s commentary ten years later, unfolded weeks after Macmillan’s speech and culminated in the murder of almost seventy black South Africans. By April, no one on any side of the color line still believed that South Africa was sui generis. South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd insisted that the crisis had “to be seen against the backdrop … of similar occurrences in the whole of Africa,” and Nelson Mandela, who was emerging as a dynamic leader in the ANC, admitted, “In just one day, [the PAC] moved to the front lines of the struggle.”Footnote 19 Neither Verwoerd nor Mandela knew what would happen next, but they interpreted Sharpeville as tacit confirmation of Sobukwe’s worldview.

Liberation

In the aftermath of Sharpeville, the ANC took steps to reinvent itself. Verwoerd’s government declared a State of Emergency in May 1960, arresting ANC and PAC leaders and forcing both organizations underground. However, the ANC’s Deputy-President Oliver Tambo had already gone abroad, where he would prove a pivotal conduit to the outside world that year. Initially, Tambo found common ground with the ANC’s rivals, forming a United Front (UF) that included the PAC.Footnote 20 Undergirding this fragile alliance was the shared assumption that the United Nations would confront apartheid because sixteen African countries joined the General Assembly that year. For the first time since 1946, sanctions seemed to be a possibility. African diplomats appeared to hold sway over the UN General Assembly’s agenda, and the All-African People’s Conference had inspired an impressive boycott of South African consumer goods in Britain and the Caribbean.Footnote 21 “[A] solution could only come from the outside,” Tambo quipped in May 1960. Theoretically, a General Assembly resolution, labeling apartheid a clear threat to peace and security, would force the UN Security Council to punish South Africa, since the 1950 Uniting for Peace resolution had ostensibly vested the General Assembly with the power to supersede an obstructionist Security Council veto. Military intervention was an unrealistic goal. Yet economic sanctions seemed feasible, and the UF saw the United Nations as a tool to destabilize the apartheid system.Footnote 22 ANC President Albert Luthuli explained the situation succinctly in 1960: “I feel that … when South African markets are affected, the people … might feel that they would be better off with another form of Government.”Footnote 23

Obvious problems came into focus immediately. On the one hand, Verwoerd’s government outmaneuvered the United Front abroad.Footnote 24 On the other hand, the PAC and ANC struggled to overcome their underlying differences. Sobukwe, whom Verwoerd imprisoned in May, hoped sanctions would destroy white rule, so South Africa could follow in Ghana’s footsteps. Luthuli, also imprisoned that year (and awarded a Nobel Peace Prize), still clung to the ANC’s vision of pluralist democracy, believing that sanctions would split European sentiment in South Africa.Footnote 25 That mindset dwindled outside Oslo as the year progressed, and the SACP did not pull its punches when Luthuli’s underlings asked for feedback in the autumn. Most foreigners, the group explained, saw the ANC’s multiracial rhetoric as a front that “concealed a form of white leadership of the African national movement.”Footnote 26 African countries in particular were suspicious of the ANC and frequently nudged Tambo to accept the PAC’s supremacy in South Africa’s anti-colonial struggle. So, the ANC could either repudiate the SACP altogether – and tacitly acknowledge the validity of the PAC’s criticism – or find a new way to frame its relationship to Pan-Africanism. Change was necessary.

Algeria offered one way forward. That country, Mandela explained in 1961, was “the closest model to our own in that the rebels faced a large white settler community that ruled the indigenous majority.”Footnote 27 With help from the SACP, Mandela won support to create a paramilitary group called uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) that year and then spent most of 1962 in North Africa – his visit coincided with Algerian decolonization – where he received training from the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN).Footnote 28 In Mandela’s mind, the juxtaposition between Ghana and Algeria could not have been clearer. Whereas Nkrumah had won sovereignty by mobilizing Africans within Ghana, the FLN had organized at home and abroad, waging a guerrilla campaign on the ground while turning French colonialism into a cause célèbre at the United Nations. The combination was important. In Mandela’s private diary, he explained:

Your tactics will not only be confined to military operations but they will also cover such things as the political consciousness of the masses of the people [and] the mobilisation of allies in the international field. Your aim should be to destroy the legality of the Government and to institute that of the people. There must be parallel authority in the administration of justice.Footnote 29

As the ANC adopted the FLN’s playbook, three things happened. First, the ANC took over the Congress Alliance. For the architects of the 1955 Freedom Charter, plurality went hand in hand with universal adult suffrage. However, at the Congress’s first post-Sharpeville consultative conference, held in in Botswana in 1962, ANC representatives argued that universal suffrage could no longer assure South Africa’s liberation. The country had to have a government controlled by people of African descent. To communicate this message abroad, the ANC declared it had to speak on behalf of the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions, the Coloured People’s Congress, and the Congress of Democrats.Footnote 30 Second, the United Front collapsed. As the ANC recast the “African image,” decoupling it from Ghana in order to dramatize Algeria’s importance, the PAC-ANC rift became unbridgeable. With the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the two organizations began to openly attack each other’s legitimacy, seeking sole support from the OAU’s newly formed Liberation Committee.Footnote 31 Third, Mandela moved to import Algerian-style war to South Africa. UMkhonto weSizwe took steps to begin a sabotage campaign at home while Tambo established a quasi-government abroad to raise funds and speak at the United Nations. Although the effort might last years, an internal ANC memorandum said that year, minority rule could “collapse far sooner than we can at the moment envisage.”Footnote 32 After all, the FLN had a government in Algiers, there was a UN peacekeeping force in the Congo, and African diplomats had just passed a resolution in New York that defined apartheid as a “clear threat” to international peace and security. Anything seemed possible.

But anything was not possible. Mandela was arrested immediately upon reentering South Africa in August, and MK was uprooted completely by July 1963. The ensuing Rivonia Trial has been chronicled extensively.Footnote 33 It overlapped with equally devastating setbacks in New York and The Hague, where the Security Council rejected the ANC’s plea for sanctions, imposing a nonmandatory embargo on military weapons instead, and the International Court of Justice vacillated over the legal status of South West Africa. South African expatriates had overestimated the implications of African decolonization, and as the mid-1960s approached, it became increasingly apparent that salvation would not come through the United Nations.Footnote 34 With pessimism encroaching, the ANC’s External Mission bifurcated between London, where white, Coloured, and Indian exiles clustered after 1960, and Lusaka, which attracted the lion’s share of black South African expatriates, especially after Zambia’s independence in 1964.Footnote 35 Once again, the situation felt tenuous.

For a time, Tambo bounced between Europe and Africa, maintaining a home in Britain and a headquarters in Tanzania. But criticism mounted as months turned into years.Footnote 36 Voices within the ANC’s London Office called for changes after the 1964 Rivonia Trial. The organization had erred by putting so much emphasis on “the [African] majority” at the 1962 Botswana conference, respondents lamented in an internal survey in 1965, and “certain persons who [were] very important in their political organisations at home” had been sidelined since that gathering. In Zambia and Tanzania, meanwhile, black South African émigrés began to question Tambo’s fitness as a military leader. Although he kept the organization afloat – mostly with aid from the Soviet Union, East Germany, and Sweden – uMkhonto weSizwe languished.Footnote 37 The relationship between the ANC and SACP remained poorly defined, and by 1965 Zambian officials were complaining among themselves that ANC freedom fighters simply wandered Lusaka’s streets with nothing to do.Footnote 38

To make matters worse, Algeria’s appeal waned in the mid-1960s. As Byrne has explained, liberation proved elusive in the so-called Mecca of Revolution. By equating freedom with membership in an international organization, the FLN trapped itself in the existing nation-state system, and the same strategy that toppled French colonialism created problems after Algeria’s independence. Guerrilla warfare had been justified, the FLN told the international community, because the French had no interest in economic development and human rights but redistributing resources while safeguarding human rights proved difficult.Footnote 39 It turned out that economic development required unpopular taxes and foreign loans, which nurtured domestic resentments, muddied the FLN’s reforms, and culminated in a military coup in 1965. (Ironically, Nkrumah, whose words had inspired the PAC, suffered the same fate a year later.) Mandela always recognized the Faustian bargain at the heart of the FLN’s strategy. Before his arrest, he had promised to “make [the ANC] more intelligible – and more palpable – to our allies,” implying that international recognition would somehow create the conditions for apartheid’s collapse.Footnote 40 He had no way of knowing that postcolonial Algeria would fall apart instead. By the time the Tricontinental Conference assembled in 1966, the ANC had lost its most prominent leader and its symbolic lodestar in North Africa.

Violence

The gathering in Havana provided a different way to think about liberation, and the timing could not have been more propitious. Tambo hit a new low that year. In London, the South African Coloured People’s Congress (CPC) left the fold. “The CPC has over the past three years patiently reasoned with the ANC leadership,” but “we have had to witness” a “campaign of slander and disruption,” perpetuated from the ANC’s African headquarters.Footnote 41 At the same time, the SACP began pressuring Tambo to stop masquerading as an Africanist and ally openly with the Soviet Union. And to add fuel to the fire, key African countries on the OAU’s Liberation Committee started to question the ANC’s legitimacy as an international organization.Footnote 42 Looking back on this period a few years later, an ANC official wrote that the group’s enemies “would have been able to wipe us out” if “not for the stubborn fact” that the ANC had “an army housed in campuses [in Lusaka] which everybody could see.”Footnote 43

However, the situation in Zambia was not ideal. Although Zambia’s President Kenneth Kaunda supported the ANC, his government was divided and his aides grumbled loudly about South African expatriates who paraded around Lusaka “wear[ing] fur hats,” promising a revolution they never intended to fight. “I do not see how [the ANC] could go on and fight in South Africa,” a Zambian official told Kaunda in these years. “Freedom fighters … want to retire from the struggle. Management and leadership is being questioned.” Even as Kaunda continued to blast apartheid publicly and cultivate his status within the newly created Non-Aligned Movement, his government put travel restrictions on the ANC and other organizations from Southern Rhodesia and Portuguese Africa. He supported these groups, in part, to avoid Ben Bella’s fate in Algeria and Nkrumah’s fate in Ghana. Zambia had no illusions about the ANC. After studying its operations in Morogoro and Lusaka, Zambia’s foreign ministry summarized the government’s mindset colorfully,

[T]he so-called leaders … have forgotten about the fight. In Lusaka they are talking about buying farms, houses, furniture and cars. … We should find if we should continue to give them money for their BEERS.Footnote 44

Cuba offered a way out of this morass. The island’s charismatic leaders – Fidel Castro and Che Guevara – positioned their revolution as a universal model for leftist anti-imperialism and armed revolt. In 1965, Guevara undertook a sojourn to Africa in a failed attempt to export this model to the Congo and Angola, and Cuban leaders retained an interest, if somewhat pessimistic, in the situation in Southern Africa.Footnote 45 Three ANC members attended the Tricontinental Conference in January 1966. While their reflections do not survive in the ANC’s archives, the visit seems to have prompted two changes. First, ANC leaders began talking about their setbacks differently. Increasingly, they blamed neocolonialism, a term popularized initially in the OAU’s 1963 charter and then embraced by the organizers of the Tricontinental meeting.Footnote 46 Nationalists had “gain[ed] political power through the mass anti-colonial struggle,” an ANC editorial argued in 1966, but “when the masses of the people force[d] their national governments to make socio-economic reforms in the redistribution of wealth, the imperialists then resort[ed] to military dictatorships through their agents.” Hence Algeria’s coup. The ANC had no doubt who was pulling the strings. “Experience has shown that this imperialist technique was perfected by U.S. imperialism in Latin America and has nowadays extended to Africa and Asia.” However, Cuba, “chosen by the peoples of these three continents as the seat of the Tricontinental Organisation,” proved that the “anti-imperialist revolution” could defeat neocolonialism. Although the struggle had faltered since 1960, Cuba “has remained the bane of all reactionary forces, especially U.S. imperialism.”Footnote 47 Because Washington responded to African decolonization with an “unholy” alliance in Southern Africa, it followed that the ANC would only prevail if it remade itself in Cuba’s image.Footnote 48

Second, the ANC updated its ideas about guerrilla warfare. Initially, Mandela’s vision for the armed struggle focused on sabotaging South Africa’s physical infrastructure since that approach seemed to have worked for the FLN. Although Mandela referred to national consciousness, he rarely explained how these methods would mobilize South Africa’s masses; he presented violence as an instrument to undercut the apartheid government’s legitimacy, which would inspire international support and divide Europeans living inside South Africa.Footnote 49 Implicitly, Mandela always believed that change required support from some white South Africans. As historian Hugh Macmillan has noted, Che Guevara’s writings turned MK’s theory of guerrilla warfare on its head. Guevara was a celebrity by the mid-1960s. His theory of revolution suggested that cadres of fast-moving militants could focus popular discontent, which would then blossom into a widely supported national insurrection. The resulting conflict would not require foreign recognition because credibility would come from peasants and laborers within the targeted country. Violence, by extension, would be an end in itself rather than an instrument to change perceptions about the South African government’s legitimacy, and it would purge the country of neocolonial agents so that real liberation would be possible.Footnote 50 With Tambo’s blessing in mid-1966, the ANC’s Lusaka office created a committee to implement this plan and then sent militants into modern day Botswana in June, September, and November. The goal was to “organise a machinery” to sort out “how people should be passing into South Africa.”Footnote 51

The subsequent Wankie and Sipolio campaigns, in which the ANC applied Guevara’s theories to South Africa, were divisive. “[T]he whole concept,” ANC political commissar Chris Hani explained, “was to build bridges, a Ho Chi Minh trail to South Africa.”Footnote 52 The Vietnam War was expanding in real-time in 1966, and Guevara’s ideas seemed to explain why Saigon’s government was starting to collapse. However, ANC forces got bogged down in modern day Zimbabwe, and they were routed by the Rhodesian military first in August and again in December 1967. Ultimately, most MK soldiers were killed; Hani barely escaped to Botswana, where he was imprisoned for a year. In his absence, the ANC halted these “lightning strikes” altogether, and when Hani returned to Zambia in 1968, he claimed to barely recognize the organization. “There was no longer any direction,” he recalled, and “there was general confusion or an unwillingness to discuss the lessons of the revolution.”Footnote 53

Tambo arguably mishandled the fallout from Wankie and Sipolio. “There were no medals,” Hani’s ally Joe Matthews later remembered. “[N]o official ceremony.”Footnote 54 But the ANC’s real problem cut deeper. Within South Africa, Verwoerd had been assassinated in 1966 and the country’s new president, John Vorster, opened a secret correspondence with Kaunda after Sipolio. Kaunda did not outline the Lusaka Manifesto until early 1969, which acknowledged Pretoria’s right to exist and asked anti-apartheid forces to negotiate with Vorster, but he disavowed violence and put severe restrictions on the ANC during 1968. For Hani, Tambo’s acquiescence to Kaunda was tantamount to neocolonial collaboration. “Professional politicians rather than professional revolutionaries” had taken control of the organization, he wrote in a widely circulated memorandum in early 1969. “Careerism,” he continued, had forestalled the revolution by creating a stagnant environment where ANC leaders attended conferences instead of waging war.Footnote 55

Ironically, Hani’s memorandum prompted a conference. The meeting was held in Morogoro in April 1969, just before Farah’s visit to Zambia, and it resolved three issues. First, the ANC opened its membership to non-Africans. The decision directly addressed the frustrations of Indian, Coloured, and white expatriates in London and consolidated Tambo’s authority there as he confronted Hani’s backers in Lusaka. Second, the ANC shrank the size of its governing council from twenty people to nine.Footnote 56 With considerable finesse, Tambo sidelined individuals who, in Macmillan’s words, were “not guerilla leaders in the Castro mode,” which tacitly acknowledged the legitimacy of Hani’s complaint while assuring Tambo controlled the fallout.Footnote 57 Third, although membership in this smaller entity was still limited to black South Africans, Tambo created a Revolutionary Council that ignored racial identity altogether. The council formalized the SACP’s place within the ANC and existed, in theory, to foster consensus around the ANC’s long-term strategy. The decision had support among MK’s rank-and-file, which had long accepted non-Africans in its ranks, and it was heralded later by ANC members and the ANC’s historians as a turning point in the anti-apartheid movement. “[A]fter Morogoro we never looked back,” Hani told an interviewer.Footnote 58 However, Jack Simons, a professor at the University of Zambia with close ties to the ANC, offered a more somber assessment. “Sometimes,” he wrote in a private letter in mid-1969, “I feel that we are involved in some great charade, a play staged for the benefit of the outside world.”Footnote 59

Solidarity

In truth, Morogoro was neither a turning point nor a charade. The ANC did not try to infiltrate South Africa again until Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, so Hani’s conclusion is obviously incorrect; yet Simons’s cynicism misrepresents Morogoro’s impact. Before parting ways, conference attendees outlined a new set of strategic and tactical imperatives. Written by the SACP’s Joe Slovo and Rusty Berstein with assistance from Joe Matthews and Duma Nokwe, these guidelines conspicuously recycled Marxist language, and journalists like Ellis have argued that Morogoro put the ANC on a course charted by the SACP.Footnote 60 But the document is better situated in a Tricontinental frame since its principal goal was to shift the ANC’s focus away from Cuba. In a 2010 interview, Matthews said explicitly that he wanted to reduce Guevara’s intellectual footprint after Morogoro, and with considerable subtlety, his strategy and tactics paper eviscerated the logic behind the Wankie and Sipolio campaigns, suggesting that an “armed challenge” – spearheaded by a well-trained revolutionary vanguard – would not “achieve dramatic or swift success.”Footnote 61 The ANC had to refocus attention on the masses at home, since “economic emancipation” required support from South Africa’s “large and well-developed working class.” This argument implied that Tambo had erred by sending MK soldiers into Rhodesia while shutting the door on another Hani-style intervention. Critically, the paper did not offer a timetable for South Africa’s revolution. Because the whole world was “transition[ing] to the Socialist system,” the strategy paper reasoned, the ANC did not have to rush things:

[The Freedom Charter], together with our general understanding of our revolutionary theory, provides us with the strategic framework for the concrete elaboration and implementation of policy in a continuously changing situation. It must be combined with a more intensive programme of research … so that the flow from theory to application – when the situation makes application possible – will be unhampered.Footnote 62

In the short-term, these words endorsed inaction, and the ensuing research program, which yielded papers on an array of topics, defended caution with considerable earnestness. Looking back on the past decade, one unnamed author lamented that the “political situation [had been] ripe” in South Africa but the ANC’s “guerilla activities” were “premature because of the backward state of [its] technical and material preparations.” Violence for the sake of violence had not accomplished anything. The paper asked the all-important question – “What then should be our approach on the question of timing?” – and argued for a flexible understanding of “what we are planning for.” Perhaps the apartheid government would be defeated in battle – like the French at Dien Bien Phu – or maybe there would be an “unexpected break in the White front making some sort of negotiations possible” – à la the Évian Accords – or maybe there would be a Congo-style UN intervention. The ANC need not engage in “useless speculation” because it did not have to precipitate events. It merely had to gird itself for “a combination of some or all of these tactics.”Footnote 63

This conclusion existed in the context of a wider conversation about Vietnam. Initially, the ANC interpreted the National Liberation Front’s (NLF) success as proof of Guevara’s brilliance, hence its own campaign to establish a “Ho Chi Minh” trail from Zambia to South Africa. However, Vietnam’s lessons were changing in the early 1970s. The NLF had not defeated the American military (and a second Dien Bien Phu was not imminent), but the NLF had sapped America’s will to fight; it seemed to ANC strategists as if perseverance and public relations went hand in hand. Internally, this conclusion teed up several realizations. First, the ANC needed to align its ambitions with its capabilities. Whereas political plans were “timeless,” and not easily defeated, the ANC could be – and had been – routed on the battlefield, and “it would be unrealistic” going forward to call upon uMkhonto weSizwe to undertake a project “large enough and effective enough to transform the situation.” Second, the ANC had to distinguish fighting from the appearance of combat readiness, since planning for “guerilla operations” was “one of the most vital factors in creating a situation in which guerrilla warfare [might] take root.”Footnote 64 Third, the ANC needed to accept that it was fighting one front in a global war to “overthrow imperialism, the reactionary ruling classes, and all other reactionaries who support the present South African regime.” Against this backdrop, ANC planners could reframe the NLF’s success as a turning point in a transnational war against neocolonialism. It followed that the United States’ defeat in Vietnam would weaken Washington’s support for apartheid, which would create a new status quo for the ANC.Footnote 65 Even if the details were fuzzy, the logic felt credible because such talk was so ubiquitous in the early 1970s.

Tambo and his backers were essentially theorizing their way out of a third direct fight with Pretoria. Unlike Algeria and Cuba, Vietnam was in the throes of an ongoing freedom struggle. By conflating South Africa’s situation with Vietnam’s war, Tambo shored up his revolutionary bona fides without ceding ground to Hani’s supporters or Kaunda’s lackeys. Yes, fighting was necessary to mobilize the masses in the long-term – and the Revolutionary Council reiterated this point at every opportunity – but the ANC could begin by allying with the “peace and progressive forces throughout the world,” shorthand for anyone who opposed American foreign policy in those years. The NLF’s “victories over United States imperialism,” Tambo explained in 1973, would “forever be a fountain of inspiration and an example to all anti-imperialist forces.”Footnote 66 The statement implied almost as much as it said. If the NLF’s “solidarity actions” could successfully “galvanize … large numbers of American people and [make] American imperialism’s domestic base very unsafe,” it followed that the anti-apartheid movement might mobilize those same forces “around the issue of colonialism and racism in Southern Africa.”Footnote 67 Although South Africa’s white population was recalcitrant, the United States was seething with discontent, and the NLF’s apparent success in winning supporters there suggested that apartheid might be attacked effectively from within North America.

Mobilizing the world’s “peace and progressive forces” presented obvious challenges but the ANC was no stranger to the complexities of solidarity politics. Since the 1966 Tricontinental Conference, it had expanded its horizon line dramatically. “Our allies are not always united,” a research paper observed in the early 1970s. The Soviets and Chinese were at each other’s throats, and African, Asian, and Latin American leaders rarely “agreed among themselves” even if they denounced white minority rule in unison.Footnote 68 Building inroads in the base of America’s imperium, among leftists who despised Washington’s support for right-wing governments, without losing credibility among socialists and nationalists would not be easy. Especially since the “malady of over-expansion” loomed over everything. “The whole world seems to be anti-apartheid,” the ANC’s Secretariat on External Affairs explained in another undated paper from this period. “Yet this world-wide campaign was diffuse, undirected and ineffective.” Hearkening back to the theme of appearances, he suggested that the ANC had to focus on “regain[ing] tactical control over this vast and diffuse campaign of solidarity.”Footnote 69 Going forward, the essential question was how.

It took the ANC another decade to settle on an answer, and the collapse of Portugal’s African empire in 1975, outside the scope of this chapter, arguably set the ANC’s course. However, the seeds of a coherent mindset could be seen before Portugal’s Carnation Revolution. Tapping into anti-apartheid sentiment was “inextricably interlinked with public relations,” an undated memorandum from the early 1970s explained. The ANC could not “hope to raise money unless the image of the organization as a dynamic force is projected in its programmes.” But there were too many differences among those who opposed apartheid to justify a cookie-cutter message. Critically, the organization looked outward, not inward, to determine an approach. It was “necessary to resuscitate in an intensive way the links with all the organizations we would like to raise funds from.” In short, the ANC had to “fragment [its] appeals to suit the fragmented character of the organizations” it encountered abroad. When working with trade unions, the “whole struggle” had to be explained as a “struggle of the workers [and] peasants” against “anti-worker fascist laws.” When reaching out to “political parties” from Asia, Africa, Europe, or the Americas, it was wiser to make “appeals on the basis of a national struggle.” It was “all a question of” finding the right “balance to achieve maximum results.”Footnote 70

Conclusion

The ANC might have adopted a different strategy during the early 1970s. It could have embraced nontraditional warfare and followed the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s example, or it could have launched a third invasion of South Africa, especially in the aftermath of Portuguese decolonization.Footnote 71 Instead, the ANC embraced the blanket claim that “imperialism [was] on the retreat” and began to tinker with its public relations toward the world’s “peace and progressive forces.”Footnote 72 This approach did not solve Tambo’s problems overnight. Zambian officials continued to make life difficult, and while Hani rejoined the fold after Morogoro, other ANC members continued to lament that a “small clique” of non-Africans had “consolidated itself” and “reorganised representation of external missions to suit its aims.”Footnote 73 Tambo sent some of his critics to the Soviet Union, where they kept out of trouble and complained about the weather, and he unfurled extensive reeducation programs at the ANC’s African camps in an effort to win the hearts and minds of his youngest followers.Footnote 74 When criticism surged again in 1975, the ANC expelled eight prominent leaders, but the stakes felt different this time. In a private letter that year, Simons wrote to a friend that he had “no clue … what [Tambo’s opponents] would undertake if they were in charge.” They had no analogy for South Africa’s future. The faction “just wanted to be leaders,” Tambo recalled. “[T]hat is all. It was a power struggle.”Footnote 75 One that Tambo won.

Was solidarity an end in itself or a means toward revolution? The question is useful because historical subjects offered different answers and changed their views over time. Like other diasporic organizations from the Third World, the ANC balanced solidarity and revolution in several ways as it implemented various plans and responded to events outside its control. Initially, the ANC believed that transracial unity would bring democratic reform to South Africa. When that argument crumbled in 1960, the ANC embraced the African image, or at least its Algerian variant. When that approach failed after 1963, the organization turned to Fidel Castro for inspiration. Many freedom fighters around the world venerated the NLF after 1968, but the ANC’s overall trajectory shows that perceptions of the Third World project evolved after decolonization and interacted with specific debates about liberation, violence, and solidarity. In 1960, the ANC looked to a cluster of African states at the United Nations when acclimating to the vagaries of life-in-exile. A decade later, the organization’s strategists had a sophisticated vocabulary to theorize and engage the so-called peace and progressive forces of the world.

The ANC is a useful prism through which to think about Tricontinentalism. Like other liberation movements, it adapted socialist ideas from Algeria, Cuba, and Vietnam. However, the ANC did not copy these models slavishly; it charted its own path, responding to setbacks that set it apart and learning lessons as events changed. This chapter has limited itself to the road to and from the 1966 Havana conference, and, admittedly, the shifts charted here were not as final as this narrative suggests. Voices within the ANC jockeyed with some of these issues for another fifteen years. However, if analogies matter, and if they shaped the ANC’s diasporic behavior, one conclusion seems obvious. Political expediency, more than age, temperament, or doctrine, informed the ANC’s understanding of and interest in Tricontinentalism.

This conclusion should not come as a surprise. Since before the 1920s activists had appealed to Geneva and then New York, using universal claims in institutions recognized as global to establish their credibility on the world stage. The ANC’s engagement with the Tricontinental Revolution extended this tradition, even as Farah’s frustrations remind us that no one person or argument ever enjoyed a monopoly on solidarity politics. The sinews of the transnational world moved through and beyond international institutions, and it remains incumbent upon historians to recognize the diversity and opportunism that underlay this peculiar, important strand of twentieth century internationalism.