Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- STAGING AND PERFORMING SOUNDS: A GLANCE THROUGH THE LAST THEATRICAL WORK

- BUILDING SOUNDS: THE COMPOSER

- CREATING SOUND: THE MUSIC BEYOND/WITHOUT THE STAGE

- REINVENTING SOUNDS: DIALOGUES WITH MUSIC OF EVERY EPOCH AND STYLE

- ACROSS BORDERS: THE CONDUCTOR AND THE INTERPRETER

- SEARCHING FOR ROOTS: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A STYLE

- STAGING AND PERFORMING TEXTS: A GLANCE THROUGH EARLY DRAMATURGICAL AND VOCAL WORKS

- Chronology Of Bruno Maderna’s Works

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Venice to Europe: Bruno Maderna Before and After 1948

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 January 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- STAGING AND PERFORMING SOUNDS: A GLANCE THROUGH THE LAST THEATRICAL WORK

- BUILDING SOUNDS: THE COMPOSER

- CREATING SOUND: THE MUSIC BEYOND/WITHOUT THE STAGE

- REINVENTING SOUNDS: DIALOGUES WITH MUSIC OF EVERY EPOCH AND STYLE

- ACROSS BORDERS: THE CONDUCTOR AND THE INTERPRETER

- SEARCHING FOR ROOTS: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A STYLE

- STAGING AND PERFORMING TEXTS: A GLANCE THROUGH EARLY DRAMATURGICAL AND VOCAL WORKS

- Chronology Of Bruno Maderna’s Works

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Summary

For apparently fortuitous reasons, it was only well into the 2000s that Maderna's production prior to his adoption of dodecaphony could be assessed in all its consistency. The late discovery of the most important scores belonging to that phase, namely, the Concerto for piano and orchestra of 1942 and the Requiem of 1946, which came to light between 2006 and 2009, allowed us to complete a “portrait of the artist as a young man” which till then was still only a rough outline. And then it also showed us that Maderna in his twenties was anything but an immature artist, albeit part of a musical world that was completely different from the one with which he had always naturally been associated. Beyond a well-defined divide marked by a date – as we shall see in a moment – his mature production begins: a relatively brief period of less than twenty-five years cut short by his untimely death in 1973, a year at the center of an era when avant-garde poetics and the related narratives were still in full force. The composer, who more than any of his colleagues was, both literally and metaphorically speaking, a “citizen of Darmstadt,” produced his main body of work in the 1950s and 1960s, the period which encompasses almost all the happenings of the post-dodecaphonic European avant-garde. It thus goes without saying that Maderna could not have partaken in the crises and afterthoughts that his generation would already experience at the end of the 1970s. Nor can we say whether the surprising eclecticism shown by Maderna in his later years, that of Venetian Journal (1972) and Satyricon (1972–73), heralded a new and not a sporadic poetic orientation. Nor should it be read as an unlikely postmodern premonition: the novelty of that polystylism coexisted with another different orientation, which was instead in coherent evolution with his previous production. Despite all their “openness” and formal mobility, his purely instrumental works, such as Aura, Biogramma (both from 1972), and the Concerto No. 3 for oboe and orchestra (1973), are completely lacking in parody and pseudo-citations from music of the past.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

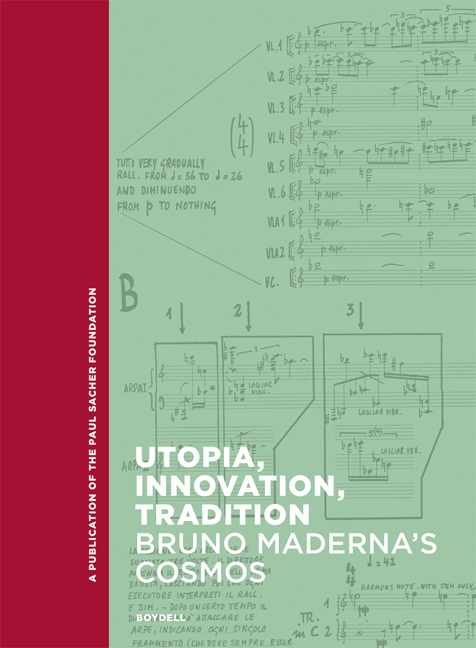

- Utopia, Innovation, TraditionBruno Maderna's Cosmos, pp. 331 - 356Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023