Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 A ‘Dangerous Model’: Resisting The Waste Land

- 2 Beyond the Sanskrit Words: Eliot and the Colonial Construction of Poetic Modernism

- 3 ‘An Icon of Recurrence’: The Waste Land’s Anniversaries

- 4 ‘O City, city’: Sounding The Waste Land

- 5 Lost and Found in Translation: Foreign Language Citations in The Waste Land

- 6 The Poetic Afterlife of The Waste Land

- 7 Compositional Process and Critical Product

- 8 Hypocrisy and After: Persons in The Waste Land

- Index

7 - Compositional Process and Critical Product

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 October 2022

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 A ‘Dangerous Model’: Resisting The Waste Land

- 2 Beyond the Sanskrit Words: Eliot and the Colonial Construction of Poetic Modernism

- 3 ‘An Icon of Recurrence’: The Waste Land’s Anniversaries

- 4 ‘O City, city’: Sounding The Waste Land

- 5 Lost and Found in Translation: Foreign Language Citations in The Waste Land

- 6 The Poetic Afterlife of The Waste Land

- 7 Compositional Process and Critical Product

- 8 Hypocrisy and After: Persons in The Waste Land

- Index

Summary

The history of The Waste Land at its centenary divides almost exactly around the publication in 1971 of The Waste Land: A Facsimile & Transcript of the Original Drafts, edited by Valerie Eliot. In his review of the publication, ‘My God man there's bears on it’, William Empson questions the book's authorial epigraph which calls his poem ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ and ‘just a piece of rhythmical grumbling.’ The reviewer notes that a ‘sheer page is given to a reported assertion by the poet, of unknown date and uncertain accuracy (surely, Eliot would never talk this kind of formal irony to Ted Spencer)’. Nevertheless, though the ‘placing of this remark gives it too much importance’, Empson was ‘sure [Eliot] did at some time say such things and believe them,’ elsewhere adding that Eliot ‘seems to have said this kind of thing when irritated by some particularly sanctimonious interpretation’. ‘What then was the grouse about?’, Empson asks, and responds by ingeniously leading biographical material from the editor's introduction back into the representations of ‘the contemporary world’ for which the poem remains both famous and notorious.

The Waste Land's first reception took it for a criticism of western culture whose account, in the first three parts, was understood to be underlined by values asserted in the final one. This interpretation was buttressed by authorial Impersonality, sustained by use of the Objective Correlative, and reinforced by the Mind of Europe via the Dissociation of Sensibility. The publication of the drafts made the poet's ‘personal … grudge’ and ‘rhythmical grumbling’ only too prominent. It pointed towards readings in which the first three sections were not so much about what was wrong with society, as what was amiss with Eliot – a reading Empson helped sketch in his review. These contrasting critical accounts (each figured by the uncertain intona- tional implications of ‘my’ in ‘Shall I at least set my lands in order?’) invite the question how The Waste Land could be both impersonal critique and personal complaint, and thus how the first three parts relate to the last. For, read personally, the poem appears broken backed: if it does affirm the spiritual values of the fifth part, then it really oughtn't to characterise the people of the first three as it does.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

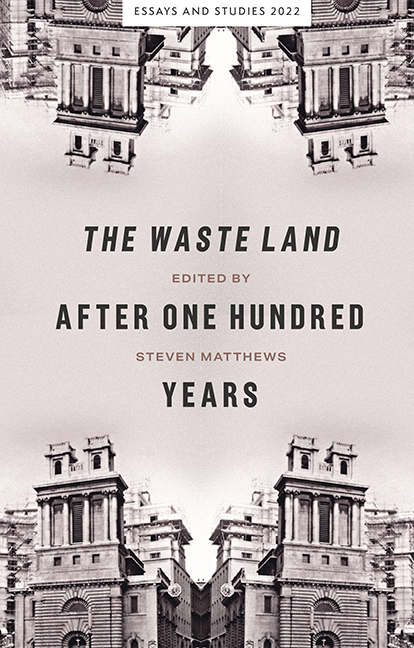

- The Waste Land after One Hundred Years , pp. 157 - 178Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022