Why did US policy-makers tear down Allentown State Hospital in 2020? The eventual demolition of that facility, described in Chapter 1, was hardly the intention of their policy-making predecessors in mid 20th-century America. As demonstrated in the preceding chapter, the political and economic conditions of the United States were broadly similar to those of France at the end of the Second World War. As the door to reforming public mental health care opened in earnest, in some ways the United States seemed to have the upper hand. Unlike France, where the war had devastated the supply of mental health services, American mental health care remained in regular use and offered a more robust infrastructure for future expansion, to which US legislators explicitly committed themselves, unlike their counterparts in France. By the early 1960s, Congress had enacted legislation to build a network of 2,000 public outpatient psychiatric clinics. This presented a key first step toward expanding public services for a highly disenfranchised community.

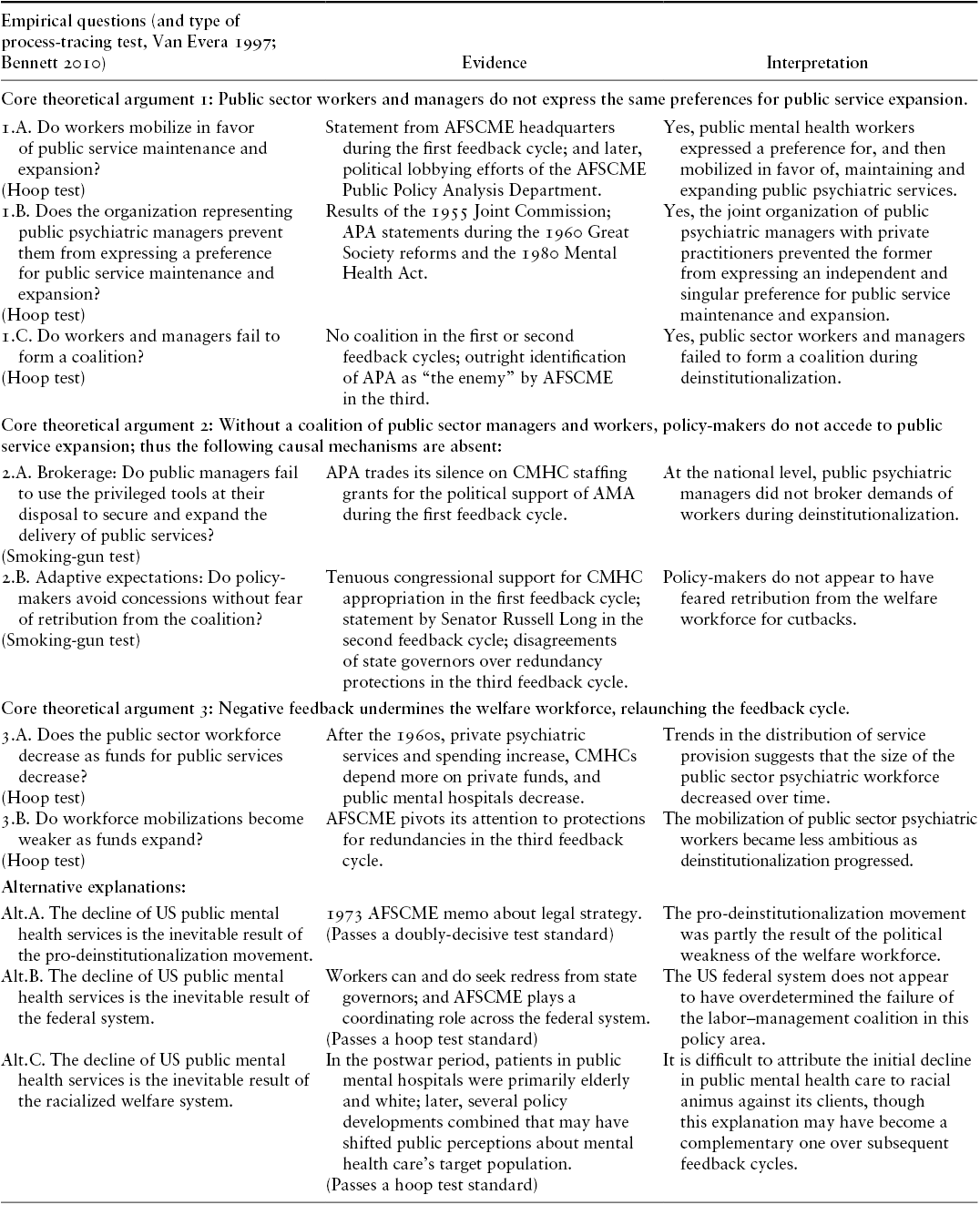

This chapter shows this apparently robust commitment to expanding public mental health care in the United States nonetheless produced the precipitous decline in public mental health service that has since gained notoriety in the international literature on psychiatric deinstitutionalization (e.g., Goodwin Reference Goodwin1997; Kritsotaki et al. Reference Kritsotaki, Long and Smith2016). Not only did the United States eventually find itself with relatively few public outpatient mental health care services, but the provision of public inpatient care also plummeted. As a result, what was once one of the largest public mental health care systems in the world became one of its smallest (see Figure 1.1). From this influential case, scholars have drawn many conclusions about the process of deinstitutionalization, including its presumed devastating effects on patients. This chapter identifies the political factors that produced such results in the United States, demonstrating how the absence of a public labor–management coalition in mental health produced three negative supply-side policy feedback cycles in the United States. Figures 4.1–4.3 illustrate each cycle in turn, and Table 4.1 at the end of this chapter formalizes how the evidence meets methodological expectations. The repercussions of these cycles have been felt in Allentown and communities like it ever since.

Figure 4.1 First supply-side policy feedback loop, postwar US mental health care

Figure 4.2 Second supply-side policy feedback loop, postwar US mental health care

Figure 4.3 Third supply-side policy feedback loop, postwar US mental health care

Table 4.1 Within-case process-tracing tests, United States

| Empirical questions (and type of process-tracing test, Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997; Bennett Reference Bennett, Brady and Collier2010) | Evidence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Core theoretical argument 1: Public sector workers and managers do not express the same preferences for public service expansion. | ||

| 1.A. Do workers mobilize in favor of public service maintenance and expansion? (Hoop test) | Statement from AFSCME headquarters during the first feedback cycle; and later, political lobbying efforts of the AFSCME Public Policy Analysis Department. | Yes, public mental health workers expressed a preference for, and then mobilized in favor of, maintaining and expanding public psychiatric services. |

| 1.B. Does the organization representing public psychiatric managers prevent them from expressing a preference for public service maintenance and expansion? (Hoop test) | Results of the 1955 Joint Commission; APA statements during the 1960 Great Society reforms and the 1980 Mental Health Act. | Yes, the joint organization of public psychiatric managers with private practitioners prevented the former from expressing an independent and singular preference for public service maintenance and expansion. |

| 1.C. Do workers and managers fail to form a coalition? (Hoop test) | No coalition in the first or second feedback cycles; outright identification of APA as “the enemy” by AFSCME in the third. | Yes, public sector workers and managers failed to form a coalition during deinstitutionalization. |

| Core theoretical argument 2: Without a coalition of public sector managers and workers, policy-makers do not accede to public service expansion; thus the following causal mechanisms are absent: | ||

| 2.A. Brokerage: Do public managers fail to use the privileged tools at their disposal to secure and expand the delivery of public services? (Smoking-gun test) | APA trades its silence on CMHC staffing grants for the political support of AMA during the first feedback cycle. | At the national level, public psychiatric managers did not broker demands of workers during deinstitutionalization. |

| 2.B. Adaptive expectations: Do policy-makers avoid concessions without fear of retribution from the coalition? (Smoking-gun test) | Tenuous congressional support for CMHC appropriation in the first feedback cycle; statement by Senator Russell Long in the second feedback cycle; disagreements of state governors over redundancy protections in the third feedback cycle. | Policy-makers do not appear to have feared retribution from the welfare workforce for cutbacks. |

| Core theoretical argument 3: Negative feedback undermines the welfare workforce, relaunching the feedback cycle. | ||

| 3.A. Does the public sector workforce decrease as funds for public services decrease? (Hoop test) | After the 1960s, private psychiatric services and spending increase, CMHCs depend more on private funds, and public mental hospitals decrease. | Trends in the distribution of service provision suggests that the size of the public sector psychiatric workforce decreased over time. |

| 3.B. Do workforce mobilizations become weaker as funds expand? (Hoop test) | AFSCME pivots its attention to protections for redundancies in the third feedback cycle. | The mobilization of public sector psychiatric workers became less ambitious as deinstitutionalization progressed. |

| Alternative explanations: | ||

| Alt.A. The decline of US public mental health services is the inevitable result of the pro-deinstitutionalization movement. | 1973 AFSCME memo about legal strategy. (Passes a doubly-decisive test standard) | The pro-deinstitutionalization movement was partly the result of the political weakness of the welfare workforce. |

| Alt.B. The decline of US public mental health services is the inevitable result of the federal system. | Workers can and do seek redress from state governors; and AFSCME plays a coordinating role across the federal system. (Passes a hoop test standard) | The US federal system does not appear to have overdetermined the failure of the labor–management coalition in this policy area. |

| Alt.C. The decline of US public mental health services is the inevitable result of the racialized welfare system. | In the postwar period, patients in public mental hospitals were primarily elderly and white; later, several policy developments combined that may have shifted public perceptions about mental health care’s target population. (Passes a hoop test standard) | It is difficult to attribute the initial decline in public mental health care to racial animus against its clients, though this explanation may have become a complementary one over subsequent feedback cycles. |

The First Feedback Loop: The Struggles of Public Community Mental Health Centers

The end of the Second World War signaled a new era for social reform, including in mental health care. The idea of “community mental health” was among the most popular concepts proposed. This held that a growing number of psychiatric conditions did not require institutional care, and in fact might find better treatment in non-hospital settings, such as outpatient clinics. But who would finance this vision, how, and to what extent? The answers to these questions would shape the viability, size, and patient base of community mental health centers, as well as, crucially, the financial interests of those staffing these centers. The lack of a coalition between public sector managers and workers in postwar America weakened the financial backing of the otherwise “bold new approach” of the 1963 Community Mental Health Center (CMHC) Act. This in turn undermined the ability of the welfare workforce to bolster that backing in the longer term. This first negative supply-side policy feedback loop (Figure 4.1), therefore, placed the outpatient side of psychiatric deinstitutionalization on unstable financial ground.

Public Workers, Managers, and Community Mental Health

In the 1950s and early 1960s, neither public sector workers nor managers were well-positioned to form an alliance on public mental health care in the United States. Public sector trade unions, as noted in Chapter 3, faced numerous organizational and legal challenges in the American states and hence lacked sufficient political power at either the local or federal levels to advocate for the expansion of public employment in mental health. The superintendents of public mental hospitals, meanwhile, lacked an independent political organization. Rather, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to which they belonged had all but removed public mental hospitals from its political agenda. By the 1950s, more than 80 percent of the APA’s membership was employed outside of mental institutions (Grob and Goldman Reference Grob and Goldman2006, 17). It is no surprise, then, that the voices that most influenced policy discussions about community mental health preferred private sector approaches to implementing the CMHC’s “bold new approach.”

The political development of the 1955 Joint Commission of Mental Illness and Health is a case in point. The commission resulted from more than a decade of growing federal investment in psychiatric medical and services research (itself in part a product of lobbying from elite researchers in private practice and universities) (Grob Reference Grob1994). Emboldened by these investments, the APA proposed a new research study: an examination of the “breakdown crisis” of overcrowded, ineffective, and under-resourced postwar state mental hospitals. Supported by its sister organization of private practitioners (the American Medical Association), the APA gained congressional authorization to establish the Joint Commission to both diagnose the problems of the mental health system and develop a program of improvement. Although the commission would include representatives from the APA and the American Medical Association, no public sector trade union participated.Footnote 1

The orientation of the Joint Commission of Mental Illness and Health toward private sector interests did not insulate it from conflict. From its small and struggling headquarters in Wisconsin, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) had expressed reservations about the influence of the private “medical lobby” on public health provision, though it did applaud the appointment of a former Massachusetts administrator, Dr. Jack R. Ewalt, to head the commission. This support was motivated by the hope that he might sympathize with the public sector cause (RL Publications 26/5; RL Zander Records 8/5). Ultimately, the recommendations proposed by Dr. Ewalt and the commission roiled government employees. The Joint Commission’s 1961 report Action for Mental Health proposed to ban the construction of state mental hospitals with more than 1,000 beds and to build a network of community clinics to reduce the need for lengthy and recurrent hospitalization. Although the report did call for more federal involvement in financing mental health care, it did not specify whether the community clinics should be private or public, leaving the answer to that important question up for grabs.

“Vociferous criticism” from state mental hospital employees followed (Grob Reference Grob1991, 212). At a 1961 meeting, government-employed psychiatrists denounced the report’s “opinions and biases” in favor of private practice (Grob Reference Grob1991, 212). Newton Bigelow, a leading New York state hospital official, wrote a series of editorials in Psychiatric Quarterly enumerating these complaints. He highlighted both the role that mental hospitals played in caring for the chronically ill and the “real problem” of staff–patient ratios as the cause of ill-treatment in those hospitals. Expanding support for public sector staff, he argued, was the better way to improve mental health care. Nonetheless, the commission’s recommendations received a formal stamp of approval from the American Psychiatric Association, as well as the American Medical Association. Indeed their members were the report’s primary authors, and they had been especially responsive to private practitioners in their recommendations (Grob Reference Grob1994, 214).

The 1963 Act Limits Public Revenues for Community Mental Health Centers

Drawing on the formalized (if contentious) recommendations of the Joint Commission, Congress enacted the Mental Retardation and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act in 1963.Footnote 2 John F. Kennedy, then president, hailed it as a “bold new approach” to American mental health policy.Footnote 3 In reality, its symbolic value may have been more significant than its practical effect. First, its content was vague, as “state, local, and private action” was identified to stimulate the vast array of recommendations. Second, its financial support for public mental health care was weak. Title II of the Act supported, but did not mandate, the construction of the Joint Commission’s proposed “public and other nonprofit community mental health centers.” No provisions were made to identify the concrete responsibilities of the “CMHCs,” nor were the funds allocated to them very large. The federal government expected states to cover a significant portion (one-third to two-thirds) of CMHC construction costs and capped the available national funds at $150 million (about $1.5 million contemporary USD; per BLS 2023) over a restricted three-year period (fiscal years 1965–67). Moreover, the appropriations that would go to academic research – not the delivery of care – took priority. Third, for strategic political reasons, the Act’s primary focus was on childhood developmental disabilities, not adult chronic and severe mental illness. Action on the former tended to yield more political support than the latter, which did not benefit from the advocacy of concerned middle- and upper-class parents. In fact, President Kennedy’s own family, which sought to redress the challenges faced by his disabled younger sister, Rosemary, helped to promote the Act.

Perhaps the most glaring omission in the 1963 Act was the absence of support for CMHC staff. The private practitioners of the American Medical Association had campaigned intensely to prevent the allocation of federal funds to items beyond construction, especially to personnel costs. Funding staff, the private practitioners expected, would promote the development of a public mental health workforce.Footnote 4 Not all of the American Medical Association members opposed the staffing provisions. Initially, it was only its Council on Legislative Activities that strongly criticized the allocation of public funds for CMHC personnel. Its Council on Mental Health, meanwhile, was somewhat more supportive of funding personnel. But in June 1963, its House of Delegates – an elected general assembly that reflected the American Medical Association’s private sector majority – voted to disapprove the Act. Conservatives in the congressional House of Representatives seized the opportunity to delete the staffing provisions (Foley Reference Foley1975, 67–69; Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 95; Grob Reference Grob1991, 231).

Caught between their public sector minority and private sector majority, as well as their close affiliation with the American Medical Association, the APA did little to protest the deletion of the staffing provisions from the Act. The APA’s threadbare presence at the July hearing of the bill, just one month after the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates overturned a key provision, indicates just how unimportant the issue was to this organization that served as the primary representative of psychiatric managers. Dr. Ewalt did testify at the hearing, first and foremost in his capacity as a community mental health expert (and not in his capacity as a representative of the APA). When asked about the APA’s formal position on the bill, Ewalt noted that it did support the bill and reminded the subcommittee that the American Medical Association had also cosponsored one of the studies that had inspired it.Footnote 5 But there was no attempt to underscore the importance of the staffing provisions, by Ewalt or any other APA members at the hearings.

The APA’s attitude toward the deletion of the staffing provisions was one of tacit permission. Had public managers in the organization formed a coalition with their employees, perhaps they would have supported these staffing provisions more forcefully, for this was precisely the kind of policy that would have bolstered public employment. But the mixed representation of the APA led the organization to develop a closer relationship with private practitioners in the AMA than with public employees. The APA appears to have traded its silence on public policies that benefit public employees for the AMA’s support for public policies that benefit private practitioners. Although in theory the APA could have supported both sets of policies, in practice the cross-pressures led the organization to make strategic choices. Strengthening its support for private practice (over public practice) maximized its chances of policy success on the dimensions most relevant to its membership and primary coalition partner. As a result, the 1963 Act offered a vague blueprint for the expansion of community mental health services, but it was tilted against a lack of stable public financing and, by extension, lack of support for public mental health workers.

Negative Feedback in Staffing Provisions

“The real question,” an internal memorandum of the Bureau of the Budget observed, “is who is going to finance operating costs [of the CMHCs] once the federal subsidies are ended” (Grob Reference Grob1991, 230). Although enactment of the 1963 Act did help to construct about 200 community mental health centers, federal administrators became aware that the program could not remain afloat (let alone reach the target of 2,000 centers) without significant, and stable, public financing (Foley Reference Foley1975, chap. 5; Grob Reference Grob1991, chap. 10). At first, legislators threw these centers a lifeline: Over the next three years, the Democratic Congress authorized about $700 million for the centers’ operational expenses.Footnote 6 But this support was short-lived. Moreover, the centers that received support in the first year would receive substantially less in the second and third years (75 percent and 30 percent of the initial amount, respectively) (Grob Reference Grob1991, 249).

Employees of the CMHCs nonetheless began to advocate for the bill’s reauthorization in subsequent years. Although the primary trade union representing public employees (AFSCME) did not formally participate, labor’s umbrella organization (the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, or AFL-CIO) agreed to coordinate lobbying activities for the bill’s reauthorization (Foley Reference Foley1975, 106). The AFL-CIO viewed the community mental health centers not only as opportunities for employment but also as a social program that might benefit their members.Footnote 7 Involved in these lobbying activities, moreover, was the APA, whose recent leadership changes had revived some attention to public practice. Moreover, the American Medical Association had agreed to temper its opposition to the CMHC staffing grants in exchange for the APA’s support on other issues of interest to private sector specialists.Footnote 8

Nevertheless, the APA still did not explicitly back public community mental health care during the reauthorization hearings. Speaking on behalf of the Association, Vice President Dr. Addison M. Duval allowed for some conflation of community care and private outpatient practice. Insisting that his colleagues had not been “sitting on [their] hands waiting for a handout from Congress,” he instead hailed how “two out of every three mental patients are being treated on an outpatient basis and the majority of them in the private sector of medicine.”Footnote 9 What he was suggesting, of course, was that Congress should do more to support community care by devoting public funds to it. After all, Dr. Duval was Georgia’s Director of the Division of Mental Health and a former employee of the federally funded St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC. But he was equally aware that most of his colleagues were uninterested in public practice. “Our task,” he offered, “is to help ensure that an ever-greater percentage of [young psychiatrists] will turn from interest in private practice to a broader application of their clinical skills in comprehensive community services.”Footnote 10 The language of “community,” “broad application,” and “outpatient basis” carefully avoided any explicit advocacy by the APA on behalf of public service workers. In fact, by distancing CMHCs from state hospitals, the APA loosened the association of mental health care with public sector provision. What is more, eventually the APA “recommended that the [CMHC] staffing grant program be changed to an operational grant program.”Footnote 11 This more muted language would allow for greater program “flexibility” and kept the concerns of private practitioners at bay by couching any support for public workers in more general language.

Absent a robust coalition between public mental health workers and managers, the staffing grants thus depended on congressional approval. Although CMHC employees could expect a Democratic Congress and president to reauthorize the funds for most of the 1960s, the Republican administrations that followed made that possibility less likely. A pattern emerged under America’s divided government of the 1970s. A Democratic Congress would renew the CMHC staffing provisions for another three-year term, the Republican president (Nixon, then Ford) would veto the bill, and Congress would override it. But the situation remained tenuous, so much so that it once required legal action. Claiming that the program was never intended as more than a demonstration grant, President Nixon’s health secretary, Casper Weinberger, impounded the CMHC funds. But the Democratic Congress protested the move, prompting D.C. District Court judge Gerhard Gesell to overturn the decision and order the funds released (Foley Reference Foley1975, 130; Grob and Goldman Reference Grob and Goldman2006, 62–63).

As the negative feedback continued, CMHC employees began to look elsewhere for funding. Without the regular, sustained, and widespread support of managers, they rarely garnered sufficient state and local funds to make up the difference from insufficient congressional grants. As a result, CMHCs found themselves depending on privately paying patients, for only they could afford the regular, lengthy therapy sessions offered by the centers. As one therapist remarked, CMHCs “began to focus on reaching more clients who could verbalize their problems – and who could pay” (cited in Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 101). Moreover, Congress eventually expanded the community mental health mandate to include services for people experiencing substance abuse and addiction, and for children. In effect, Congress shifted emphasis on serving groups with less intensive, and therefore less costly, needs than those of people with chronic and severe mental illness (Foley Reference Foley1975, 126; Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 101). This shift meant replacing services intended for the seriously mentally ill (access to medical care, housing, employment) with services for those with milder conditions (marriage counseling, family therapy).

In fact, the demographic shift in the CMHC population was so pronounced that analysts coined an acronym for its new clientele, YAVIS: young, attractive, verbal, intelligent, and successful (Schofield Reference Schofield1964, 133).Footnote 12 Very few CMHC patients had severe needs, let alone needs that had required hospitalization.Footnote 13 At first, CMHC patients tended to be from poorer and non-white backgrounds, at least in urban areas. But as the first negative feedback loop played out over the next few years, only 15 percent of the total CMHC patient population would fall under the schizophrenic category, the condition that most strained public budgets (Grob Reference Grob1991, 261; Grob and Goldman Reference Grob and Goldman2006, 47). As CMHC employees turned to private revenue sources to preserve their employment, poor patients with severe mental illness were beginning to fall through the cracks.Footnote 14

The Second Feedback Loop: The Exclusion of Public Mental Hospitals from the Social Security Amendments

While negative supply-side policy feedbacks constrained the supply of public community mental health centers, another set of negative feedbacks reduced the supply of state and county mental hospitals (Figure 4.2), the main public providers of inpatient psychiatric care. On average, states allocated nearly a tenth of their overall annual budgets to paying for these facilities.Footnote 15 The situation changed in 1965 with the landmark enactment of the Social Security Amendments. This major federal intervention in health and social welfare policy nonetheless excluded state and county mental hospitals. In doing so, it shifted the financial incentives of states by facilitating the transfer of patients out of the hospital setting. In some cases, former psychiatric patients entered private elderly care homes; younger patients did not have that option. The result was a gradual decline in both patient numbers and, by extension, revenues of state and county mental hospitals through the late 1960s and 1970s. Although state public employees had begun to pick up political and legal momentum at this time, they lacked the necessary support of their managers to demand that the Social Security programs expand coverage to mental hospitals.

Moreover, the negative feedback loop rendered them unable to prevent the 1972 enactment of disability insurance from further exacerbating this problem. Long-term public hospital patients, already excluded from the 1965 Medicare and Medicaid programs, then became unable to access disability benefits. Thus, the absence of a coalition between public mental health care workers and managers reduced the availability of federal funds for their patients and, accordingly, their services.

Public Workers, Managers, and Hospitals

Although a select number of states had begun to grant legal rights to organize to their employees by the mid 1960s, the vast majority of employees in state and county mental hospitals remained unorganized at this time. In general, their perspective was absent from the debates on the Social Security Amendments. The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees did signal an interest in the bill in a letter to the congressional Committee on Ways and Means, but it did not explore – or perhaps was even unaware of – its implications for current state hospital employees.Footnote 16 Following the general lead of the AFL-CIO, the small and locally fragmented AFSCME instead focused its attention on the bill’s implications for aging workers. The adoption of federal pension and health insurance programs would reduce the union’s own obligations to provide these benefits to their members.

While state employees were too unorganized to advocate for public mental hospitals in the bill, the APA focused its efforts on using the bill to support private psychiatric practice. By then, one of the APA’s presidents had publicly stated that the state mental hospital was “antiquated, outmoded, and rapidly becoming obsolete” (Grob Reference Grob1994, 223). Although a small minority of public psychiatrists in the organization protested this image, the APA did little to redress it. Instead, the organization sought to include private psychiatric services in the basket of elderly care benefits provided by the generous new Medicare program. Moreover, the APA’s focus was on private outpatient services. It did little to prevent legislators from curtailing Medicare coverage of public inpatient psychiatry, which may have benefited the state and county mental hospitals. In fact, as one APA representative testified, “other types of facilities [than state hospitals] can often render more appropriate treatment at far lower cost – private psychiatric hospitals, day hospitals, outpatient departments, community mental health centers, and so on.” The APA unofficially but effectively estranged private practice from public psychiatry to draw greater resources to the private sector at the expense of the public sector.

The 1965 Social Security Amendments Exclude State and County Mental Hospitals

The absence of a coalition between the workers and managers of state and county mental hospitals facilitated the exclusion of these services from the 1965 Social Security Amendments and subsequent legislation. First, the headline Medicare health insurance program and expanded Social Security pension program dramatically reduced the population of elderly patients living in state and county hospitals. Prior to the Amendments’ enactment, about one out of every three persons admitted to a mental hospital was over 60 years old, a proportion that had increased by 40 percent in the preceding two decades, as rising female labor force participation and the baby boom challenged the possibility of domestic elderly caregiving.Footnote 17 The Medicare program offered elderly Americans health coverage, including in the area of private outpatient psychiatry (due in part to the advocacy of the APA), though it limited the total number of days they could spend as hospital inpatients to 190 days (in their lifetime). Moreover, elderly residents could use the resources offered by the expanded pension, Social Security, to obtain other services. Consequently, Medicare incentivized elderly patients to seek medical coverage outside of the state and county hospital, while Social Security supported their access to alternative custodial care.

Second, Medicaid precluded covering services provided in “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs), which further motivated states to transfer their indigent patients out of state and county mental hospitals. As Laura Katz Olson has detailed, the Medicaid program was an “afterthought” to the 1965 Social Security Amendments, “slipped in” by Wilbur Mills (D-AR) to provide health insurance for the blind, the disabled, and families participating in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program (Katz Olson Reference Katz Olson2010, 22–27).Footnote 18 Needy patients in mental hospitals were likely to qualify for the new Medicaid program. At the state level, governors and administrators welcomed the opportunity to share the costs of those patients with the federal government, but at the federal level, few in Congress were willing to take on these costs. “When we get into this field [of mental health care] it is going to cost a lot of money,” said Senator Russell Long (D-LA).Footnote 19 Facing no resistance from the welfare workforce, Congress thus easily excluded IMD payments from the basket of Medicaid benefits (hereafter, the IMD Exclusion). Senator Long’s reasoning, moreover, made it difficult for federal policy-makers to include extensive noninstitutional care in the benefit structure of either Medicaid or Medicare. Again facing no resistance from the welfare workforce, Congress presumed that states would continue to provide mental health care services, inpatient and outpatient, on their own dime for the foreseeable future.

Third, Congress enacted a small piece of pork barrel legislation on the heels of the 1965 Amendments that effectively subsidized state mental hospitals’ competitors: private elderly care homes by tweaking the federal tax code. The technical and complex bill went through numerous twists and turns, seemingly unnoticed by those in the mental health field (let alone the general public, for that matter). The bill first emerged in the House in March 1965, sponsored by Representative John Byrnes, a Republican from Wisconsin, where a recent survey had found a “serious shortage” of facilities.Footnote 20 Although temporarily overshadowed by the Social Security Amendments, the proposal then reappeared in the Senate in September 1966 when Senator Jack Miller (R-IA), of the Committee on Aging, tacked it onto a bill intended to control the costs of tax collection (the IRS had recently implemented a new automatic data processing system). The addition of Section 7, on nursing homes, to the bill would “save the taxpayers several million dollars,” his colleague Senator Long assured.Footnote 21 At that point, there was enough general agreement among the senators to pass the bill and send it to the House. A joint committee then developed more specific conditions about the “modest profit” available to nursing homes.Footnote 22 It stipulated that profits would depend not only on services delivered but also on the costs spent on buildings and construction. Reimbursing based on a reasonable charge instead of a reasonable cost, furthermore, would incentivize both private for-profit and private not-for-profit services to build new nursing homes. Public nursing homes were excluded since they were not driven by the profit motive. On November 2, 1966, President Johnson assented, signing legislation “requiring the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to permit the nursing homes a modest profit when reimbursing them for their services to Medicare patients.”Footnote 23 This seemingly small policy change delivered significant rewards to private elderly care homes, but not state and county mental hospitals.

Negative Feedback in the 1972 Social Security Amendments

The American states henceforth took advantage of these policy changes to reduce their hefty budget lines for public mental hospitals. The federal government’s affirmative support for private nursing home care and private psychiatric benefits, combined with its refusal to cover care provided in public institutions, deinstitutionalized the elderly out of mental hospitals and into care homes. Between 1965 and 1972, the rate of admission of individuals over 65 to state and county mental hospitals fell by half, from 146 per 100,000 to 69 per 100,000. The locus of care for these individuals thus shifted from asylums to nursing homes: Between 1960 and 1970, the number of nursing home facilities increased by 140 percent, of nursing home beds by 232 percent, and of nursing home patients by 210 percent (Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 103). Although this shift away from state and county mental hospitals was especially pronounced among the elderly population, Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion had also begun to incentivize the deinstitutionalization of younger indigent patients.

As a result of this evolution, the revenues of state and county mental hospitals declined sharply, weakening their workforce further. Moreover, managerial representatives continued their estrangement from the public sector. The APA’s positions had evolved: It began taking a stronger stance against Medicare’s 190-day limit on inpatient treatment, as well as in favor of lowering coinsurance costs for Medicare outpatients and expanding Medicaid coverage of mental health services in private general hospitals.Footnote 24 Lengthening the duration of Medicare coverage for inpatient treatment would benefit private psychiatric and general hospitals; lowering coinsurance costs for outpatient care would benefit clinicians in private offices; and the removal of Medicaid restrictions for poor patients in general hospitals would reduce the volume of care in state and county mental hospitals. Although it had somewhat adjusted its policy positions, the APA supported policies that benefited the majority of its members, those in private practice, and did little to support the minority of its public practitioner members.

By the early 1970s, there was little the welfare workforce was able to do to prevent federal legislation from repeating the pattern it set forth in the 1965 Social Security Amendments. The 1972 Social Security Amendments – which replaced state welfare programs for the aged, the poor, the blind, and crucially, the disabled with the federally administered Supplemental Security Income program – also excluded payments to people residing in state and county mental hospitals (and indeed, in public institutions more generally, for similar cost-control reasons).Footnote 25 Records show no indication that either AFSCME or the APA expected the eligibility exclusion, in part because both groups were more concerned with the bill’s immediate implications for their members. The union’s narrow focus was on how the possible “federalization” of welfare might displace local social service employees, not on the effects of the bill for psychiatric patients served by state and county hospital employees.Footnote 26 Expanding Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits to include those in public institutions, in its view, would have little immediate effect on the livelihood of its members. This 1972 policy thus encouraged states to also transfer disabled patients out of state and county mental hospitals. The year following the program’s enactment saw a record reduction in the institutionalized population: 13.3 percent (Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 103).

The negative policy feedback that resulted impacted not only the employees of state hospitals but also their patients. Although the relocation of deinstitutionalized patients was a shrewd financial move for the states, it was far from benevolent. A few “psychiatric ghettos” arose in urban centers near deinstitutionalizing hospitals, primarily for the indigent Medicaid patients who lacked a custodial alternative.Footnote 27 That many of these patients were eligible now for disability benefits (as long as they did not reenter the institution) reinforced these trends. As private entrepreneurs converted run-down hotels and houses into boarding homes and halfway houses, former mental patients often found themselves living together once again, but this time without professional medical attention. A study in New York City shortly after the passage of the 1972 Amendments found that one in four residents of the city’s “welfare hotels” once resided in a public mental hospital.Footnote 28

The elderly patients who now lived in nursing homes, moreover, were not much better off either. Soon enough, about half of nursing home residents were living in cramped facilities with more than 100 beds, and about a third of those patients in facilities with more than 200 beds. The majority of these facilities lacked trained medical staff and few offered the psychiatric care necessary for those with serious conditions (Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 102–3). What had occurred was not the deinstitutionalization of patients from the hospital into the community but rather the trans-institutionalization of patients from a medical institution to a merely custodial one, if they could find one.

The Third Feedback Loop: The Formal Retrenchment of Public Mental Health Services

By the early 1970s, the first and second feedback loops had placed severe financial strain on public mental health services. First, only about 400 (out of the projected 2,000) CMHCs had received federal funding.Footnote 29 Not only was there dwindling political support for the reauthorization grants but neither had the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid offered much additional support. States were responsible for determining Medicaid reimbursement rates for CMHCs, and Medicare had not given the centers the status of designated (covered) provider (PCMH 1978, 31). Second, the deinstitutionalization of state and county mental hospitals had reduced revenues to the point that many states now considered closing their hospitals wholesale. That the scandalous conditions in these underfunded institutions had reached the public’s ears only exacerbated the pressure to close hospitals.

In addition to these domestic policy pressures, public mental health services also faced financial strain from international factors. The economic shocks of the early 1970s had prompted governments to scale back their public budgets. The ongoing war in Vietnam, moreover, motivated American officials to withdraw funding from mental health and other social welfare initiatives and instead devote it to defense and military operations (Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 98). In short, public mental health services – and their employees – were facing financial pressures on multiple fronts.

The third negative feedback cycle (Figure 4.3) resulted in the formal retrenchment of public mental health services, both inpatient and outpatient. What is different about this third feedback loop is that public sector workers, now more robustly unionized at the state level, took on a much more active role in resisting these pressures than they had when contending with the first two feedback loops. Nonetheless, workers were unable to form an alliance with their managers, who remained beholden to the representation of the private-oriented American Psychiatric Association. The absence of such a coalition rendered the welfare workforce much less capable of renewing and expanding public funds for mental health care, even when a window of opportunity opened under the Carter administration in the late 1970s. Debilitated and divided, public employees could do little to resist the shattering cutbacks to mental health subsequently enacted under the Reagan administration.

“The Enemy”: AFSCME and the APA

By the 1970s, far more states had extended legal and organizing rights to their employees. With the accrual of those rights, public sector unions had become larger and more influential. Of these workers, an overwhelming number worked in public mental health care services. Nearly one in four members of AFSCME – 250,000 of one million – were employed in mental health facilities (RL PPAD finding aid). In fact, the union’s membership was so affected by deinstitutionalization that it made that issue the primary focus of its Public Policy Analysis Department in its newly established Washington, DC headquarters in the early 1970s.Footnote 30 The union was clearly now aware that federal developments were as consequential for its members as state-level ones.

The new AFSCME department’s strategy was two-pronged. First, it would launch a massive public relations campaign to highlight the negative aspects of deinstitutionalization and to respond to criticisms inveighed against hospitals. The union had hired journalist Henry Santiestevan, formerly the editor of the UAW monthly Solidarity and a regular public relations consultant to César Chávez and the United Farm Workers, to assist the campaign (SNAC n.d.). Santiestevan’s report, “Out of Their Beds and into the Streets,” emphasized how deinstitutionalization had resulted in “crime, nursing home scandals, and community protests,” calling the process a “shell-game for budget cuts, layoffs, and profiteering” (RL PPAD 1/1). In response to these trends, AFSCME demanded “more money”; and, as a member of the AFSCME Public Affairs office elaborated in a memo to Santiestevan: “More doctors and nurses. More training and better reliance upon para-professional and support staff. A removal of ‘profit’ as a factor in care for the mentally indigent” (sic, Hamilton 1975 in RL WR 60/2). After decades attempting to gain a political voice, public sector workers could now advocate for more revenues to be channeled toward providing mental health care.

Their managers, primarily represented by the APA, were, however, not keen to support the AFSCME. The APA’s public sector membership was dwindling. At state mental hospitals, a quarter of positions for staff psychiatrists remained unfilled (Grob Reference Grob1991, 253). Private psychiatry, meanwhile, was booming. Between 1968 and 1972, the United States added 26 private psychiatric hospitals, all of them for-profit and owned by the many new private corporations entering the health care market.Footnote 31 Spending on private outpatient psychiatry now exceeded seven billion dollars (in contemporary USD; per BLS 2023).Footnote 32 The financial basis of these funds came neither from the new federal insurance programs nor from private insurance companies, which lacked a national mandate to cover costly mental health services (Grob Reference Grob1991, 264). Instead, out-of-pocket payments financed the vast majority of private office practice. A study conducted in the early 1970s found that these offices focused almost exclusively on patients with neurotic conditions from the professional and managerial classes. Blue-collar workers, white-collar (nonmanagerial) workers, and schizophrenic patients were underrepresented among patients. African Americans and Hispanics were “virtually absent” from these offices (Grob Reference Grob1991, 294). In short, the APA’s client base had shifted dramatically away from those of state and county hospitals and community mental health centers.

The political-economic interests of AFSCME and the APA were so poorly aligned that AFSCME even referred to the APA as “the enemy,” precisely because of its “private sector tilt” (see Wolf to McGarrah 1979 in RL PPAD 3/2). This is not to say that the union did not attempt to form a coalition with its adversary. In a speech to the APA in Philadelphia in 1970, Jerry Wurf, AFSCME’s then president, argued that “hospital management can do more … to please and benefit the worker, and consequently, to change the atmosphere surrounding the patient” (RL WS 1/21, 10). But the APA did not accept Wurf’s invitation to collaborate. In the same speech, Wurf himself had acknowledged the glaring inequalities of public mental health work. While physicians had raised fees “at a rate 50 percent faster than the cost of living … the wages of non-supervisory hospital personnel average[d] less than subsistence level in private, non-profit hospitals.” The mental health system “helps nobody but the richly rewarded therapists,” he would later add in a 1975 speech (RL WS 1/113, 9). In short, AFSCME – having only just found its political footing – saw that a coalition with managers was far from possible.

When a window of opportunity to change mental health policy opened in the late 1970s, therefore, the welfare workforce was not positioned to take advantage of it. Upon his election to the presidency in 1977, Jimmy Carter set up a new President’s Commission on Mental Health, a decision prompted, in part, by First Lady Rosalynn Carter’s personal interest in mental health.Footnote 33 The commission’s composition, however, implicitly favored private psychiatry. Bemoaning the paltry presence of labor representatives, AFSCME noted that “most other Commissioners are management or advocates of deinstitutionalization,” that is, opponents of public sector psychiatry (see the 1978 memo in RL PPAD 3/6, 2). “Management,” of course, included the APA.Footnote 34 To counter the private sector’s influence, AFSCME requested that the commission appoint its vice president, Albert Blatz, to the Task Panel on Deinstitutionalization, Rehabilitation, and Long-Term Care (RL PPAD 3/6, 1978 memo, 2). The request, though successful, ultimately did little to advance the union’s interests in the sea of competing policy positions. In the commission’s final report, the mental hospital chaplain was listed as “Father Albert Blatz, St. Peter State Hospital, St. Peter, Minnesota” (PCMH 1978, 83). No mention was made of his position within AFSCME.

Unsurprisingly, this commission’s recommendations favored private psychiatry as well. Although its final report acknowledged the importance of public finance for mental health care provision (and even went so far as to support the campaign for national health insurance), its more immediate, more realistic recommendations sought to bolster private care. The report recommended that Medicare benefits, for example, should be amended to cover CMHCs and more acute and short-term hospitalization, as well as to reimburse more outpatient care (all services based largely in the private sector). Moreover, the report said nothing of Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion. Instead, it criticized the Medicaid program for covering too much institutional care (including in nursing homes). The report asked that states extend Medicaid to pay for more outpatient mental health services and that they invite private health insurers to do the same. Furthermore, the report encouraged the “phase down and where appropriate closing of … large State mental hospitals” (PCMH 1978, 29). Little was said about the other factors, outside of the health system, influencing deinstitutionalization. A vague recommendation that the administration “explore the feasibility of creating a new system to meet the costs of chronic mental disability” was the only reference that acknowledged the role of the 1972 Social Security Amendments in deinstitutionalization. Personnel recommendations focused not on protecting and expanding public employment but rather on the need to diversify the workforce and develop new curriculums (PCMH 1978, 34). Taken as a whole, the commission’s recommendations would benefit private community mental health services – what AFSCME once disparagingly called “Rosalynn Carter’s pet cause” – over any form of publicly provided care for poor patients with mental illnesses.Footnote 35

The 1980 Mental Health Systems Act Subdues Public Mental Health Care and Its Employees

The recommendations of the President’s Commission directly influenced the resulting Mental Health Systems Act, passed on October 7, 1980. Though lauded as a landmark bill, the legislation in fact undermined public mental health services and its employees. The bill did extend several grants for community mental health centers and other services, but no effort was made to guarantee these funds for the longer term. This unstable fiscal provision reflects the divided positions of managers and workers. During the congressional debates about CMHC funding, the APA and AFSCME developed fundamentally different narratives. “Without being self-serving,” APA representative Dr. John McGrath exclaimed, “private practitioners and facilities have, in many instances, been left out of the mainstream of the evolution of community mental health.” Legislation, in his view, should “go further to provide adequate incentives to the private sector.”Footnote 36 Encouraging health insurers to cover private outpatient mental health services to the same degree as other health care services was the APA’s preferred remedy. Public sector workers, of course, strongly critiqued the APA’s victimization narrative:

Those [patients] who have been denied decent treatment from the private mental health care establishment have been consigned to the public institutions where AFSCME members strive to do the best jobs they can under terribly trying circumstances.Footnote 37

The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees advocated that the legislation provide for the state operation of community mental health centers, as well as for the continued support of longer-term state mental health care facilities.Footnote 38 After years of mistrust between these two organizations, it was at these hearings that public workers were left most obviously bereft of support by their supervisors.

No attempt was made, furthermore, to redress the gaps in public mental health care coverage created by the 1965 and 1972 Social Security Amendments. This issue, too, lacked the agreement of managers and workers. While AFSCME repeatedly campaigned to eliminate Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion and expand federal disability benefits to those residing in public institutions, the APA remained vague on these issues. Consider the differences between the testimony of both groups. Dr. McGrath of the APA asked Congress to “provide adequate resources, including major modifications in Medicaid, Medicare and the Social Security Disability Insurance to underwrite the income maintenance as well as the non-discriminatory treatment costs for these individuals,” but he was not specific about what those modifications should be. Robert McGarrah of AFSCME, however, explicitly requested that:

The SSI [Social Security Disability Insurance] program must also be changed: There is no justification for prohibiting patients in public institutions with more than 16 residents from receiving these funds, when that money is made available to patients in private facilities, even if hundreds of SSI recipients reside in them; Medicaid must be amended to remove funding inequities that prohibit institutional coverage for persons 21–65.Footnote 39

In comparison, federal disability insurance and Medicaid – two social programs for the poor – received little attention from the APA. Such specificity about policy change was only given to Medicare, which the APA still hoped would cover private services more generously.

Perhaps the clearest indicator of the weakness of the position of the US welfare workforce in the 1980 Act was its forced acknowledgment of the inevitability of redundancy, a reality that will contrast sharply with that of their counterparts in France (discussed in Chapter 5), since they secured their position at the height of economic retrenchment. The American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees sought to convince Congress to disburse CMHC grants only to states with which the union had negotiated protections for laid-off hospital workers. To do this, AFSCME turned to another set of elected officials: state governors. Several key members of the National Governors Association, however, opposed such restrictions. After all, the governors had few incentives to support this strategy. Exchanging CMHC funds for employee protections would make those funds more difficult to access, not to mention prolong the state’s financial obligations to workers it no longer needed. Noting the particularly prominent opposition of Pennsylvania’s Republican governor Dick Thornburgh, AFSCME turned to his fellow Pennsylvania Republican, Senator Richard Schweiker, a key member of the Subcommittee on Health, for support. Schweiker had once endorsed the idea that the federal government distribute the CMHC funds via the states (previously the funds went directly to the centers). The tactic was successful. A revised bill required the state-level distribution of the CMHC funds and made their uptake conditional on the negotiation of employment protections.Footnote 40

Negative Feedback Prompts Full-Scale Cutbacks to Mental Health from the 1980s Onward

Whatever optimism there was for the Act because of this change, however, lasted less than a month. The political weakness of the welfare workforce was no match for the results of the November 1980 elections. Not only had the Republicans regained the presidency with the election of Ronald Reagan but their control of the Senate also gave them command over a congressional chamber for the first time since 1953. The success of the Republican Party concluded a decade of partisan realignment and ideological reinvention. The party opened the next decade with a more developed neoliberal strategy for reform. In so doing, it moved swiftly to pass the 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, legislation that dramatically restructured federal spending and reduced support for social programs.Footnote 41

Public mental health care was not spared with this Act’s passage. Neither the APA nor AFSCME testified at the 1981 bill’s sprawling hearings; and the new legislature fully repealed all the financial provisions of the1980 Mental Health Systems Act.Footnote 42 Congress converted the CMHC appropriations into a flexible block-grant program, financed at levels 75 to 80 percent below those promised by the Mental Health Systems Act. The block grants carried few restrictions and no guidelines (Grob and Goldman Reference Grob and Goldman2006, 114–15). State hospital workers lost the protection guarantees they had fought for in the former bill. Private community mental health services, too, would suffer. Limiting the support for the less than 800 CMHCs in operation (a meager fraction of the intended 2,000) meant the program dwindled over time. As of the 2010 National Mental Health Services Survey (SAMHSA 2014), CMHC block grants fund just a third of psychiatric outpatient facilities in America.

Locked into Negative Feedback Loops

In the following years, AFSCME continued to lobby on behalf of its laid-off members. A new public relations document prepared for the early 1980s, “Patients for Sale,” doubled down on the language and policy positions of “Out of Their Beds and into the Streets” (RL WR 22/12). It encouraged union locals to add full-time positions devoted to coping with deinstitutionalization (McGarrah to Wurf in RL WR 22/12, 4). In 1980, the Public Policy Department projected spending nearly $400,000 on materials to train its staff on how to negotiate contracts for deinstitutionalizing hospitals (McGarrah to Cowan in RL WR 22/12, 1; in contemporary USD per BLS 2023). But the union lacked the political allies required to be effective. A strategy document from that year makes no mention of involving the APA in its political activities, and instead notes its struggle to find potential partners: “AFSCME stands alone so far in opposition to irresponsible deinstitutionalization” (McGarrah to Wurf in RL WR 22/12, 4).

The return of the Right also meant the exclusion of labor from federal policy-making. The appointment of one AFL-CIO representative to the 44-member Task Force on Private Sector Initiatives was the only official involvement of the Federation in the Reagan administration (McGarrah to Lucy et al. in RL PPAD 16/19). Evidently, the goals of the Task Force did not favor public sector employment. For this reason, the reduction of public mental health services continued. Over the latter half of the 20th century, the number of state and county mental hospitals dropped by well over a third (from 334 at their 1973 peak to 207 in 2003; see table 2 in Atay et al. Reference Atay, Crider, Foley, Male and Blacklow2006). Moreover, the scant availability of positions in the community mental health sector made it difficult to support the transfer of their former workers to non-hospital settings. In contrast, in France, mental health workers would be able to work across the full range of inpatient and outpatient settings of the psychiatric sectors (see Chapter 5).

The APA remained passive about many of the core policy issues affecting public mental health services, such as Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion and the training of staff for public services. The Association remained active in issues that supported private practice. For example, when the Reagan administration began to purge young people with disabilities from the disability benefit programs to save costs, the Association convened a working group at the Social Security Administration in 1983 to revise the programs’ eligibility criteria. The result was the expansion of benefit categories and the requirement that a psychiatrist or psychologist complete a medical assessment for disability claimants before benefits could be denied.Footnote 43 Later, in 1985, the APA and the American Hospital Association collaborated to exclude psychiatric specialty inpatient care from Medicare’s new prospective payments. The system paid hospitals an average rate in advance for care according to a system of categories known as the “diagnosis-related groups” (DRGs). Excluding costly psychiatric care from this system helped to protect the revenues of private providers (Grob and Goldman Reference Grob and Goldman2006, 141). By the 1990s, the mentally ill accounted for more than a third of disability beneficiaries (Erkulwater Reference Erkulwater2006, 117). It was not until 1999, furthermore, that Congress modified the DRG regulations and implemented a per diem prospective payment system for inpatient psychiatry (Pub. L. No. 105–13).

Initiatives led by career bureaucrats in the federal government did seek to make a few incremental policy changes in support of public mental health services. Notably, a group of public sector supervisors – state mental health directors – encouraged these changes. These state officials lacked the influence of the APA (which could also claim to represent many of them), but they nonetheless worked with the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to establish a National Plan for the Chronically Mentally Ill.Footnote 44 The plan was ambitious and included numerous specific changes to federal programs (including Medicare, Medicaid, and SSI) that would boost support for public sector care. Since the economic and political climate proved too hostile to implement the plan through legislation, the federal government instead pursued smaller scale projects. One of these was the 1986 Program on Chronic Mental Illness to finance the reorganization of local mental health delivery systems in nine large cities. These grants also permitted mental health authorities to subsidize rents for people with mental illnesses. Homelessness had become a pressing problem for the noninstitutionalized since the Reagan administration also cut funds for public housing support. Baby boomers presenting symptoms of schizophrenia (a condition that develops in young adulthood) were among the most affected. They lacked the medical and employment history necessary to both access and afford chronic psychiatric care in the post-asylum era.Footnote 45 However, it was the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, not government, that funded this $80 million program.Footnote 46 Indeed, programs like these illustrate the tenuous state of mental health services in America even until today. Short-term, small-scale programs for the most vulnerable cannot rely on secure, long-term public financing, and thus depend on the goodwill of charitable institutions.

Meanwhile, a more stable source of psychiatric care has emerged in a less desirable location: prisons. In a study published in 1984, Steadman and colleagues found that while the state mental hospital population decreased by 64 percent in the 1970s, the prison population increased by nearly the same amount (65 percent). The finding supported the classic sociological hypothesis that “if the prison services are extensive, the asylum population is relatively small and the reverse also tends to be true” (Penrose Reference Penrose1939). However, the authors of the study, like many others who have examined the expansion of the American carceral system, underscored that the relationship was not quite so simple in the United States. Many of the factors that spurred mass incarceration had little to do with those that deinstitutionalized the mentally ill (e.g., the reliance of victims’ movements on law-and-order politicians in absence of a supportive welfare state, the criminalization of drug activity, and the lucrative development of the private prison industry).Footnote 47 But the connection remains. As Parsons explores, the same conservative politicians who reduced funds for welfare and medical services also paid more attention to security and punishment. Those who had been involuntarily confined in mental hospitals were now often involuntarily confined in prisons instead (Parsons Reference Parsons2018). Causes aside, the result was that many people with mental illnesses found themselves living in prisons, which in turn became providers of mental health care (Fuller Torrey et al. Reference Fuller Torrey, Fuller, Geller, Jacobs and Ragosta2012). Some of the largest psychiatric institutions are in fact prisons (Ford Reference Ford2015). As Lara-Millán (Reference Lara-Millán2021) has shown, the US prison system is poorly equipped to support people with mental illness, aggravating the inadequacies of the medical system in this area.

Although the Reagan (and then George H. W. Bush) era was followed by a period of Democratic governance, the Clinton administration adopted a Third Way approach to social spending (as did many of its peer governments in other countries). The economic retrenchment of the 1996 welfare reforms exemplifies how Democrats continued many of the policies inherited from the Reagan era. A small window of opportunity emerged for public psychiatric workers (and patients) during the attempts to enact a universal health program in the early 1990s, but this proved too costly for insurers, and too unattractive to private practitioners, to succeed in Congress. The return of the Right in the early 2000s continued to favor maintaining the status quo. It was not until the enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 under President Obama that some attention was paid to financing mental health services, and even so, the bill’s mental health reforms were limited, as noted in the discussion of the American mental health system in Chapter 2. Moreover, the core challenge of financing mental health reforms endures. To date, the CMHC program hardly exists, insurers have limited incentive to cover psychiatric care, and Medicaid excludes “institutions for mental disease” from its benefit package.

Alternative Explanations

In the preceding pages, I have argued that the absence of a coalition between public sector workers (represented primarily by AFSCME) and managers (represented primarily by private practitioners in the APA) produced negative policy feedback loops that gradually reduced the supply of mental health care services and the overall strength of its workforce. Although the next chapter will demonstrate how the presence of such a coalition produced the opposite result in France, here I consider three main alternative explanations for the American outcome.

First, I explore whether and how pro-deinstitutionalization social movements played an outsized role in reducing services in the United States. Second, I address the role of American federalism in producing these outcomes. Third, I consider whether postwar development of the American welfare state – which became increasingly racialized, restricted, and privatized as a whole – influenced the trajectory of mental health policy. Each of these explanations helps to fill out the picture of deinstitutionalization in the postwar period, but none offers a sufficient account of its core policy drivers.

Alternative Explanation 1: The Pro-deinstitutionalization Movement

There is no question that the public support for deinstitutionalization gained political momentum in the United States. Some might even go so far as to call it a social movement.Footnote 48 Its development, however, was more a symptom than a cause of underfunded public mental health care. In the words of a leading AFSCME lobbyist, “virtually every patient’s rights lawsuit in this country can be traced directly to overcrowding, understaffing, and inadequate funding of state institutions” (McGarrah to McKinney in RL WR 28/14, 10). Hollywood, the press, and the academic community rightly drew attention to the often inhumane and scandalous conditions of the decrepit state and county mental hospitals. Public outcry rightly followed. Rather than support the expansion of public funds, however, these complaints unconsciously aligned with the interests of private psychiatrists. As Dunst (in Kritsotaki et al. Reference Kritsotaki, Long and Smith2016) has also argued, these movements both arose from and contributed to the pattern of deinstitutionalization in America.

Consider the example of academic social criticism. A number of social scientists, both in the United States and abroad, had begun to question the dominance of the psychiatric profession as arbiters of social norms. The publications of scholars such as Thomas Szasz (e.g., The Myth of Mental Illness, 1961, and The Manufacture of Madness, 1970) and Erving Goffman (most notably, Asylums, 1961) circulated among readers who were sympathetic to similar liberationist ideas in Black, feminist, and other critical thought. Many of them responded by rejecting state-operated psychiatric services, believing that the termination of these services would result in the termination of psychiatric oppression, too. When this academic conversation was taken up by the public, however, it had the unintended consequence of bolstering arguments for privatizing services. For example, many private clinical psychologists espoused a milder form of this anti-psychiatric critique by arguing against the medical model of mental illness. Given the difference between their clients and those of the public mental hospitals, their therapeutic services were sustainable with less public funding. Drawing on these arguments to advocate for licensing and certification equivalence, the profession became more popular and its size nearly doubled in the 1980s (Grob and Goldman Reference Grob and Goldman2006, 47).

A similar pattern followed in the courts. Building on critical legal scholarship that equated involuntary commitment to a mental hospital with incarceration in a prison without due process (Birnbaum Reference Birnbaum1960), advocates began to pursue legal recourse for patients mistreated by state psychiatry in the 1960s.Footnote 49 A subsequent ripple of court decisions in the early 1970s made it more difficult for states to treat patients against their will.Footnote 50 But by chipping away at government authority in the area of mental illness, these decisions inadvertently facilitated the ongoing financial retrenchment of its services. Reducing treatment became easier than imposing it.

Politically, welfare workers were too weak to reverse these trends. Delayed mobilization by AFSCME affected its potency in the courts as much as it did in Congress. In a 1973 internal memo, nearly two full years after the first court ruling in 1971, an analyst raised the point that:

AFSCME has not utilized the full potential of the court decision … it would seem that Wyatt v Stickney could be used by us in numerous cases to demand adequate staff and facilities both for the patients and for the employees. It could also become an important factor in the whole problem of closing down institutions.

Although the memo included a host of research on how to reframe the ruling as an advocacy tool for significant service expansion, that same year the Supreme Court was already ruling that involuntary commitment was illegal in all cases of “non-dangerous” individuals. Those “capable of surviving safely in freedom” should do so.Footnote 51 This decision made it even more difficult for AFSCME to advocate for service expansions. Moreover, the financial means available to support AFSCME’s surmised strategy had dropped precipitously in the intervening years. Rather than raise revenues to provide adequate staff and resources, by that point states were more likely to respond to inadequacies by shutting down institutions in their entirety.Footnote 52

Alternative Explanation 2: American Federalism

Scholars of American social policy often point to the role of the country’s fraught federal–state relations as a factor driving its fragmentation (Lieberman Reference Lieberman1998; Mettler Reference Mettler1998; Michener Reference Michener2018).Footnote 53 Public mental health services, too, encountered this challenge. The lack of coordination between, on the one hand, federal-level CMHC grants, Medicare, Medicaid, nursing home grants, and disability insurance and, on the other hand, state-level hospital financing contributed to America’s mishandling of deinstitutionalization. Complicating matters further was that the state-level policies also varied. This variation affected not only when, where, and to what extent public employees could unionize but also what their mental health policy agenda might be. In fact, for most of the 1970s, AFSCME lacked a unified policy position on deinstitutionalization. “As I understand it,” the author of a 1979 internal memo worked out, “we [AFSCME] are totally against it [deinstitutionalization] in Pennsylvania, with a modified acceptance in New York State, [and] in Milwaukee we are both against and for” (Dowling to Wurf in RL PPAD 34/4). How could the welfare workforce fully respond to budget cuts with so little federal–state coordination and so much cross-state variation?

Although the following chapter will discuss how French workers in fact used policy decentralization precisely to promote their interests, several developments in the American case also question the extent to which federalism is solely to blame for its mental health care outcomes. First, the cross-state variation in mental health policy in effect underscores the critical role of public labor–management coalitions. That workers could not form this alliance with their supervisors at the federal level does not mean that they could not do so at the state level. Note that the vast majority of public mental health care employees were local, not federal, employees, so they first sought redress from state governments (and governors, as the third feedback cycle showed). Indeed, the presence or absence of that coalition at the state level often contributed to the local variation in public mental health financing and services.Footnote 54 Coalition formation at the state level nonetheless became more complicated as federal and private health services and benefits developed, for they offered managers more opportunities to exit public employment and enter private practice.Footnote 55

At this point, and second, AFSCME took on a robust coordinating role between the federal and state levels. Consider its actions during the passing of the 1980 Mental Health Systems Act. Turning to an alternative set of public supervisors, state governors, the workers managed to rewrite the terms of the federal bill: States would receive CMHC funds only if they negotiated employment protections for state hospital workers. Although workers were not able to develop this coordination until it was too late in the deinstitutionalization process, they nonetheless demonstrated a capacity to supersede the challenges of federalism to promote their economic interests and procure revenues.

Alternative Explanation 3: The Effect of Race on the American Welfare State

As in other countries, the welfare state expanded in the United States after the Second World War. Unlike other countries, however, it also developed its more racialized, limited, as well as privatized character. The distribution of US social benefits often falls along racial lines, with limited public social provision for low-income, non-whites and more generous, if privatized, social provision for whites employed both formally and stably. Did this pattern of distribution also shape the mental health care outcomes? Limited research has examined this question. A possible answer proceeds in two parts:

To begin, it appears that this logic could not initiate the decline of public mental services in the early part of the postwar period. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the population of institutionalized patients was primarily elderly and white.Footnote 56 This group was broadly perceived as “deserving” of social support, indeed this presumption was an important driver of the 1965 Social Security Amendments, which redistributed generously to that group. Perhaps perceptions would have been different had the patient populations of state and county mental hospitals been primarily non-white and working age, two factors (race and ability to work) that can code benefit recipients as “undeserving.” But this was not the case. Rather, as illustrated, the APA and AFSCME seemed more concerned with the distributive implications by patient diagnosis, which largely shaped their ability to pay for their own care. As private services for the milder conditions of the YAVIS population grew, public services for indigent patients with chronic and severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia, declined. In keeping with the theoretical expectations laid out in Chapter 1, only public sector employees advocated on behalf of the most disenfranchised.

By the late 20th century, however, several developments combined that may have shifted the perceived target population of mental health policy away from elderly white women and toward unemployed, homeless, even “violent” Black men. First, the Great Migration of African Americans from the American South to northern cities rendered them a more visible, urbanized population in the eye of the public in the 1960s.Footnote 57 When deindustrialization then displaced many of these (mostly male) Black workers from their northern industrial jobs in the late 1970s, it left them highly dependent on means-tested social welfare programs. That these benefits experienced the sharp social welfare cuts of the 1980s and early 1990s only exacerbated Black urban poverty and, in many cases, homelessness. The comingling of this population with those recently deinstitutionalized on the streets and in halfway houses (all of whom were also targets of the racially coded “war on drugs”) ultimately produced the image of “psychiatric ghetto” in the public’s mind (Gillon Reference Gillon2000, 104; Grob Reference Grob1991, 261). This characterization, both unfair and untrue, nonetheless may have shifted public presumptions about the mentally ill, undermining the perceived deservingness of expanded public mental health services over time. Consider the emergence of “NIMBY” – Not In My Back Yard – campaigns in the late 20th century. Public outcry over the psychiatric ghetto tended to rally around making it less visible, not delivering the medical, housing, and employment services necessary to address its root causes.