Part III - Living with technology

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 January 2024

Summary

Finding ourselves somewhere between the ideological extremes of techno-optimism and techno-pessimism, we are somewhat ambivalent and just a little confused.

Everyone is still on social media, but it seems that there is an emerging art of living with social media that involves something like: delete all your accounts right now! While social media giants stick by their stated ambition to unify the world, they are in fact, as Brad Evans and Chantal Meza point out, “creating islands of isolation, the likes of which we have never seen before”. Perhaps the art of resistance in the face of ever-more refined and numbing tech seductions is simply (to channel both Bartleby and Žižek) preferring not to?

Tech visionaries have a venerable history of cheque-inthe- mail promises: in the 1960s, Marvin Minsky promised us Hal-style robots “in a generation”; in 2005, Ray Kurzweil declared that “the singularity is near” (Kurzweil sets the date as 2045, which conveniently means he will probably have died shortly before he is proven wrong); prophecies of a forthcoming AI apocalypse get tongues wagging. The reality, however, is far more mundane. Even the LaMDA system that made global headlines last year when a Google engineer claimed it was sentient is, once the stardust settles, just an impressive text production programme. It seems that the art of living with technology is also the art of cultivating a good nose for bullshit.

Iris Murdoch noted that we are creatures who make pictures of ourselves, and then come to resemble that picture.4 Seemingly oblivious to the long history of using the latest technological innovations (from catapults to telephone switchboards) as a model for understanding the mind, the hypothesis driving most modern cognitive science these days is that our minds are literally computers or algorithms. The plausibility of the transhumanist dream of liberation from corporeality and finitude depends on this. But what do we give up and how do we distort our natures when we acquiesce to the powerful, gendered fantasies of a rather bloodless tribal creed?

Despite these misgivings, we all know that it is coming, no matter what …

- Type

- Chapter

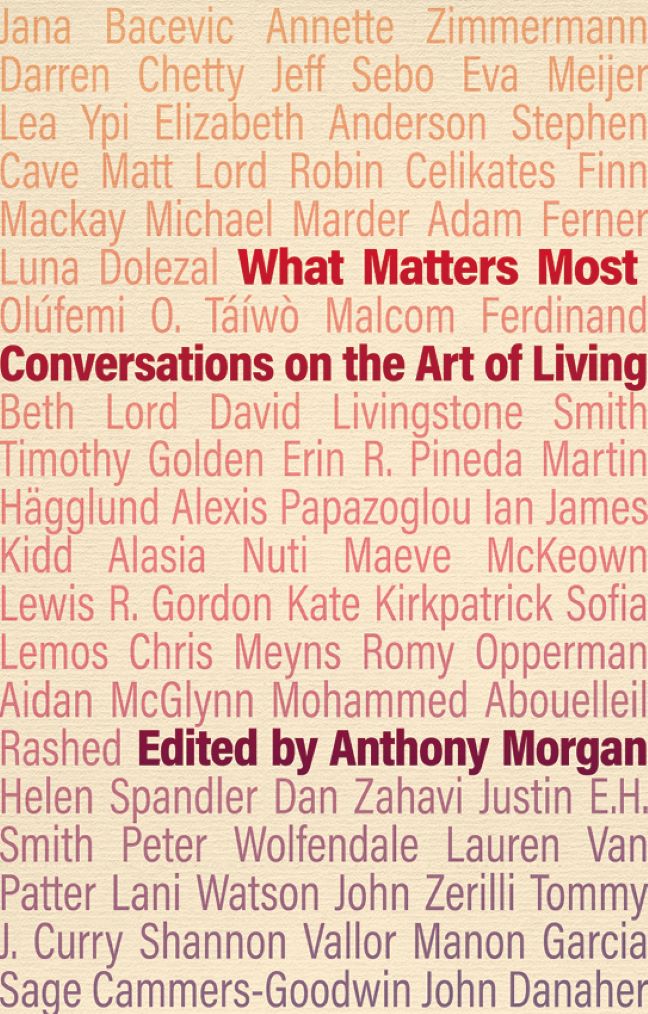

- Information

- What Matters MostConversations on the Art of Living, pp. 115 - 116Publisher: Agenda PublishingPrint publication year: 2023