12 - Relationality and political commitment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 January 2024

Summary

Our Euromodern philosophical inheritance via thinkers like Hobbes, Locke and Mill is of an atomistic and non-relational being who thinks, acts and moves along a course in which continued movement depends on not colliding with others. In this conversation, Lewis R. Gordon proposes a relational model of humanity inherited from southern Africa, Asia, South America, and even parts of continental Europe. For Gordon, this relational understanding of ourselves allows for the opening up and transformation of the possibilities of being human, all the way through to rethinking our institutional and political relations. While the Euromodern model views political commitment through the self-interested prism of success and failure, the relational model represents a profound critique of how most of us have come to fix action at an individual level. Seen in this light, Gordon argues that we must rethink the philosophical anthropology at the heart of a specific line of Euromodern thought on what it means to be human.

LEWIS R. GORDON is Professor and Head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Connecticut. His work spans Africana philosophy, existentialism, phenomenology, social and political theory, postcolonial thought, theories of race and racism, philosophies of liberation, aesthetics, philosophy of education and philosophy of religion.

OLÚFÉ.MI O. TÁÍWÒ is an assistant professor of philosophy at Georgetown University. His theoretical work draws from the Black radical tradition, anti-colonial thought, philosophy of language, contemporary social science, and histories of activism and activist thinkers.

Olúfé.mi O. Táíwò (OOT): In your work, political responsibility is something that goes beyond moral responsibility, and certainly beyond moralism. You use the example of Harriet Bailey to exemplify one model of political responsibility. Harriet Bailey was the mother of abolitionist and political thinker Frederick Douglass, and the two of them were separated at birth, which was a common aspect of chattel slavery at the time. When Douglass was around seven years old, Bailey found out that she was enslaved on a plantation 12 miles away from where he was growing up, and she walked the distance in the evenings to spend time with him into dawn, when she returned to the fields. Shortly after this, she died. Why do you see Harriet Bailey as an exemplar of your idea of political responsibility?

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

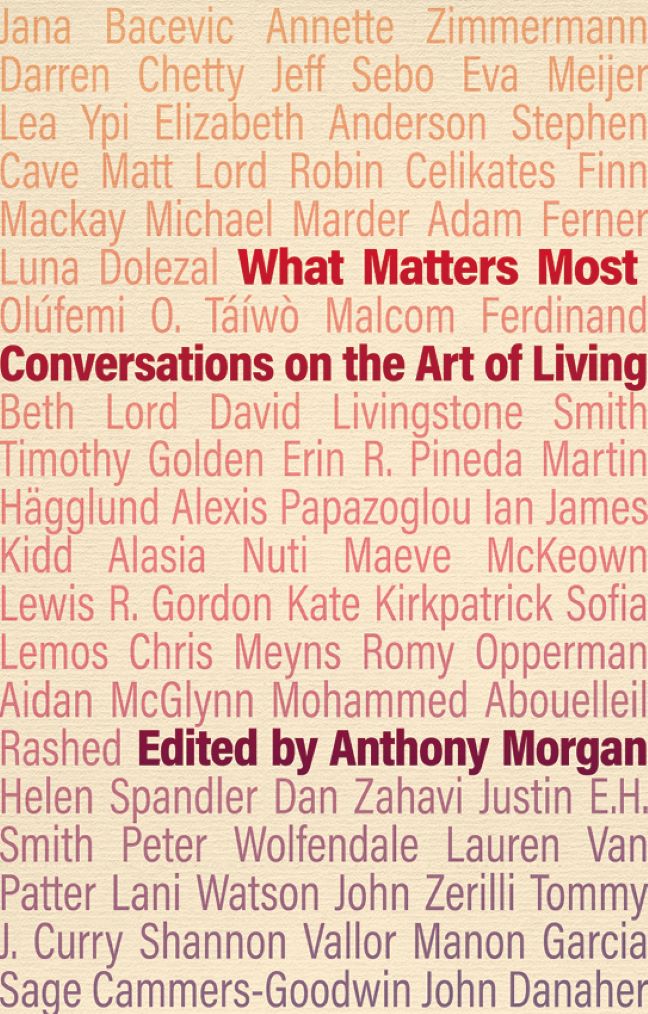

- What Matters MostConversations on the Art of Living, pp. 107 - 114Publisher: Agenda PublishingPrint publication year: 2023