21 - Spinoza in the Anthropocene

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 January 2024

Summary

What can the enigmatic early modern philosopher Baruch Spinoza contribute to our thinking about the climate crisis, and specifically, our thinking about the emotions generated by it? In this conversation, Beth Lord argues that for Spinoza, that which increases human action and thinking is good, and deriving energy from fossil fuels has been a very great human good over the past 400 years. But we now understand our reliance on fossil fuels to be bad for our flourishing and that of other forms of life on earth. We can no longer rejoice in the consideration of collective human power; instead, we now fear its devastating predicted effects. What are the implications of this fear of our own power? What confusions does this fear emerge from? And how can we correct and clarify our emotional response to the climate crisis, especially the future-oriented emotions of hope and fear?

Beth Lord is a philosopher and professor in the School of Divinity, History and Philosophy at the University of Aberdeen. She specializes in the history of philosophy, especially the work and influence of Immanuel Kant and Baruch Spinoza, as well as contemporary continental philosophy.

Chris Meyns is a poet, developer and architectural conservationist based in Uppsala, Sweden. They have published on the history of data, on Anton Wilhelm Amo's philosophy of mind, and the legacy of the philosophical canon.

Chris Meyns (CM): The climate emergency is very much alive to us right now. We are already noticing global heating, species going extinct, ice caps melting, floods and droughts. Spinoza, by contrast, lived in the seventeenth century, and didn't write about this catastrophic process. Maybe he did not foresee that anything like this might ever happen. What got you thinking about linking this seventeenth-century philosopher to this urgent contemporary topic?

Beth Lord (BL): The key idea that is relevant here is Spinoza's naturalism, as this really challenges how we think about the Anthropocene and the climate emergency. Spinoza is a monist, so he believes that all of being is one being, and this one being is called “God or Nature”. Individual things like human beings and objects and animals and plants are not independent substances; rather we’re the changing “modes”, or ways of being, of “God or Nature”.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

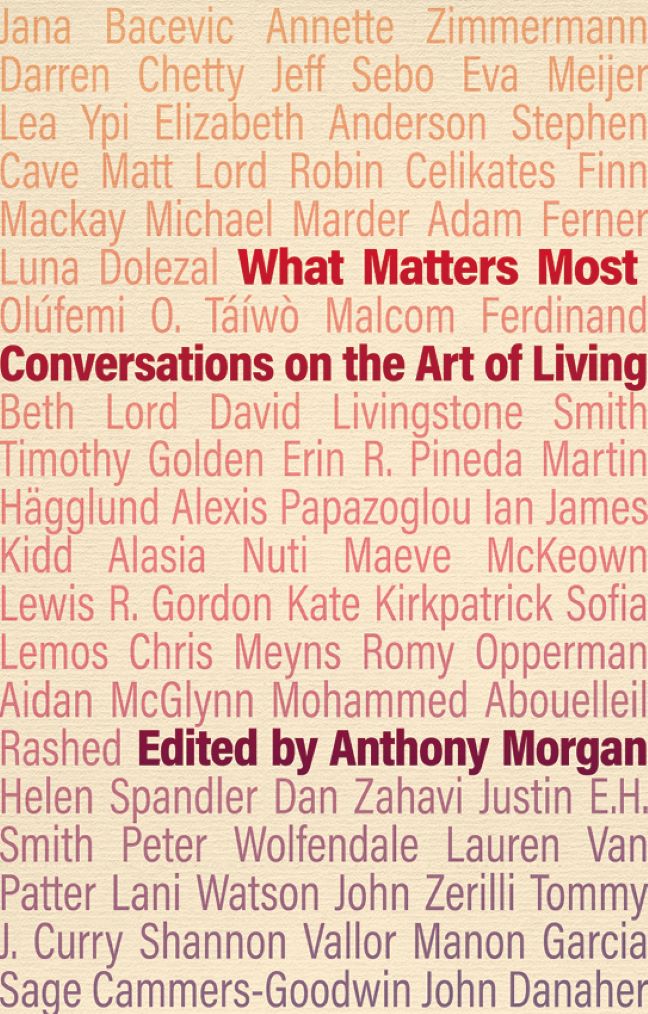

- What Matters MostConversations on the Art of Living, pp. 193 - 202Publisher: Agenda PublishingPrint publication year: 2023