18 - We and the robots

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 January 2024

Summary

We are living through an era of increased robotization, with robots becoming integrated into settings such as factories, hospitals, transportation systems, military, workplaces, households and healthcare. But what are the social and moral implications arising from our interpersonal connections with robots? Can robots have significant moral status? Can we be friends with a robot? When your robot lover tells you that it loves you, should you believe it? In this conversation, philosopher of technology John Danaher considers whether we are robots ourselves; whether we should understand our relationships with robots by analogy with non-human animals; whether robot friendships can complement and possibly enhance human friendships; whether robots have an inner life; whether robots are capable of deceiving us; and much more.

JOHN DANAHER is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the National University of Ireland (NUI) Galway. He researches on a wide range of topics at the interface of philosophy, law and technology, and he is host of the popular “Philosophical Disquisitions” podcast.

ANTHONY MORGAN is editor of The Philosopher and commissioning editor for philosophy at Agenda Publishing.

Anthony Morgan (AM): In an interview, the philosopher Kevin O’Regan said that he believes he is a robot, and, furthermore, that people get upset when he tells them that they are robots because they feel that they’re persons and not robots. He goes on to say that the fact that he is a robot doesn't mean that he doesn't suffer pain or fall in love or appreciate art. It just means that there are no “magical mechanisms” explaining these phenomena, such as free will. What insights do you think we can glean from thinking about whether we are robots ourselves?

John Danaher (JD): I consider our world to be a collection of mechanistic structures knitted together in very complicated ways, and so we are in principle very sophisticated mechanisms. Hence if we can create mechanisms that are as sophisticated as us – they may not be exactly functionally equivalent but they may behave and act in much the same way – then they can have all the qualities and attributes that we have, and possibly others too. Thus there's no reason for me to think that we can't create general artificial intelligence or robots that are effectively the same as humans.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

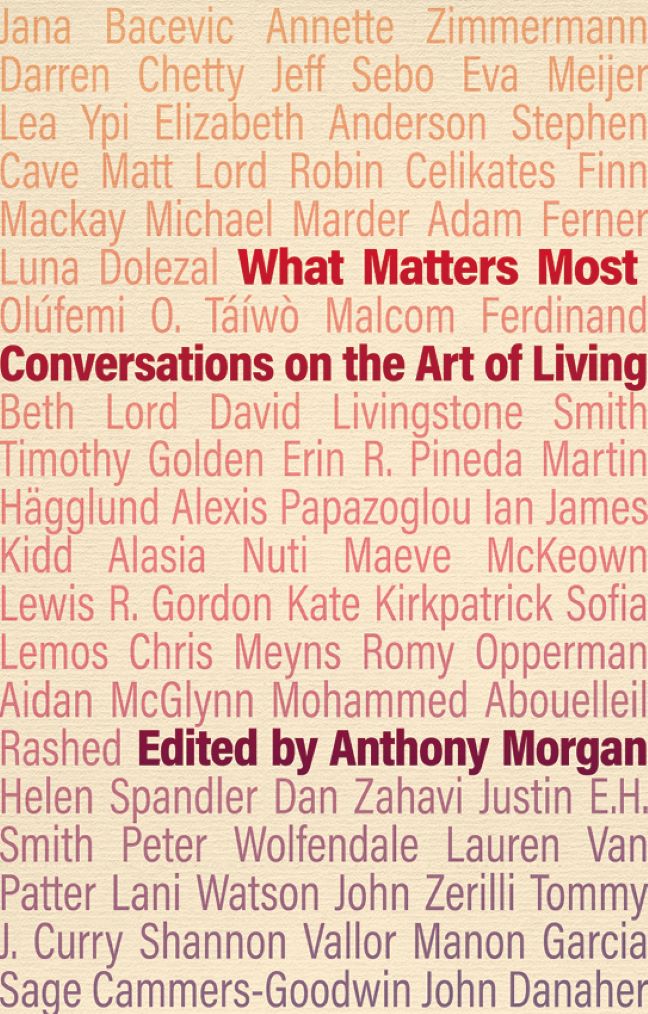

- What Matters MostConversations on the Art of Living, pp. 163 - 170Publisher: Agenda PublishingPrint publication year: 2023