Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Piercing the Skin of the Present

- Part I

- Part II

- 5 Show Them What Cleaning Is: This Time It's for Mama

- 6 Who Can See this Bleeding? Women's Blood and Men's Blood in these #Fallist Times

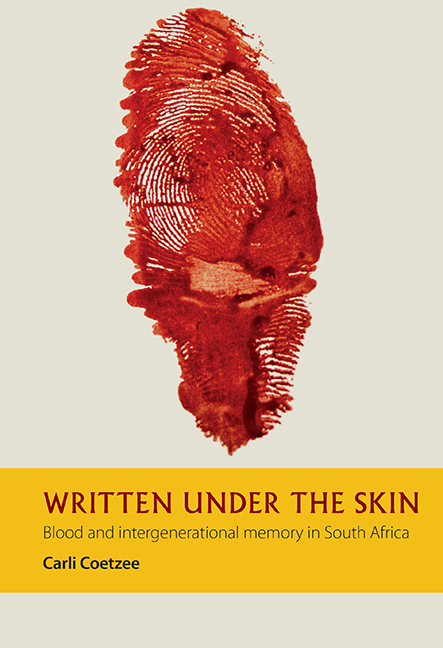

- 7 The Bloody Fingerprint: We Must Document

- Bibliography

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

6 - Who Can See this Bleeding? Women's Blood and Men's Blood in these #Fallist Times

from Part II

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 March 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Piercing the Skin of the Present

- Part I

- Part II

- 5 Show Them What Cleaning Is: This Time It's for Mama

- 6 Who Can See this Bleeding? Women's Blood and Men's Blood in these #Fallist Times

- 7 The Bloody Fingerprint: We Must Document

- Bibliography

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

On the opening night of the first Abantu Book Festival in the Soweto Theatre, on 8 December 2016, the poet Lebo Mashile was more exuberant than normal. Striking in her blood-red dress, she welcomed the audience, celebrating the importance of the occasion and saying: ‘It has been a gap in our hearts for a long time’, to murmurs of assent from the audience (http://www.abantubookfestival. co.za/). Her comments about a ‘gap’ referred to the absence of spaces such as Abantu where black South Africans could gather to discuss books and ideas. The nature of the ‘gap’ did not need to be glossed for the audience, although its significance might be missed by others less attuned to the ways in which the publishing industry and literary culture in South Africa have worked to marginalise Blackness/blackness and black reading audiences. On two historic days in early December 2016, Abantu Book Festival would be the venue for a number of discussions, roundtables and informal conversations about the nature of this ‘gap’. Abantu's aim was to facilitate a space where Blackness/blackness was centred and assumed, and then from that centre to talk about pain, particularly black pain, testimony and ‘our stories’. The website of Abantu says: ‘This is the space we've been yearning for. Let there be healing.’

The inaugural edition of Abantu Book Festival made explicit the dynamic interconnectedness between reading and the continuous work of bringing a particular self into being. ‘Abantu Book Festival: Imagining Ourselves into Existence’, was the slogan of the festival. The location (Soweto), the name (abantu, the plural of the Nguni noun umntu which means a [black] person) and the emphasis on ‘ourselves’ are all distinguishing marks of the activist vision behind this literary festival. The photographs taken, and the videos made of the panels and gatherings, are now available online. These constitute an archive as well as a resource, creating and preserving beyond the physical gathering what Litheko Modisane in his book on cinema audiences calls ‘black-centred publics’ (2013). The archived videos emphasise, if the title of the festival did not already do so, the significance of Abantu in laying claim to a vibrant and already existent literary culture with long histories, and crucially as black and black-centred.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Written under the SkinBlood and Intergenerational Memory in South Africa, pp. 121 - 146Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2019

- 1

- Cited by