The number of countries affected by armed conflict and forced displacement is expected to rise over the next decade, resulting in challenges to human development and socioeconomic integration.1,Reference Bendavid, Boerma, Akseer, Langer, Malembaka and Okiro2 Key concerns pertain to the mental health of conflict-affected populations,3 systems of psychiatric care and the effectiveness of interventions to support psychosocial well-being. This article presents a synthesis of extant literature on mental health issues, systems of care and culturally relevant interventions for conflict-affected Afghans. It is authored by 30 scholars, practitioners and programme managers, mostly Afghan nationals, who led work on Afghan mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS). We sought to document significant accomplishments to date, and provide a comprehensive overview to support MHPSS initiatives relevant to Afghans and conflict-affected people globally.

Afghanistan: sociopolitical developments in the last 40 years

Strategically located at the crossroads of empires in India, Persia and Russia, Afghanistan has a long and turbulent history of war.Reference Tanner4 In 1979, Soviet forces invaded the country to support the fragile communist regime that had taken control of Afghanistan.Reference Rubin5 There followed intense resistance from Afghans who rejected attempts to ‘Sovietise’ the country through modernising efforts that clashed with Afghan traditions, encroached upon family decision-making and expanded public roles for women in society.Reference Dupree6 Deep divisions between Afghan communities and their ruling elites sparked a 10-year war (1979–1989) that was fuelled by massive financial support and supply of arms from foreign powers. Over 6 million Afghans became displaced, the vast majority of whom fled to neighbouring Iran and Pakistan.Reference Rubin7 Following Soviet withdrawal in 1989, civil war ensued between rival ‘mujahideen’ factions, leading to the destruction of much of the capital city of Kabul. This conflict was quelled by the rise of the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist group originating among the Pashtun, the largest ethnic group in the country, which promised stability and rule of law.Reference Maizland8 The Taliban maintained control of 90% of the country from 1996 until they were ousted in 2001 by an international military intervention led by the USA.

After 20 years of Western-backed reconstruction and increasing insurgence, the international forces withdrew in 2021, followed by a rapid takeover of the country by the Taliban and the abrupt termination of the Afghan Government in August.9 Just before the 2021 Taliban takeover, Afghanistan's Human Development Index was 0.51, positioning the country as 169th out of 189 nations worldwide in terms of life expectancy, education and overall living standards.10 Since then, the situation of women and girls, as well as religious and other minorities, has worsened. Moreover, the economy has suffered dramatically as a result of disrupted markets and the freezing of central bank reserves and loans, pushing millions into extreme poverty and leaving an estimated 55% of the population in need of immediate humanitarian assistance.11,12 Many healthcare accomplishments are now in peril, given the regime change in 2021 and the withdrawal of international assistance.Reference Silove and Ventevogel13

Afghanistan: Documenting mental health initiatives and research

The past 20 years saw ground-breaking initiatives to establish systems of care to address mental health needs in Afghan populations. Notably, a public mental healthcare system was developed, in-country, to train new cadres of mental health professionals and psychological counsellors and to integrate mental health within the nation's basic healthcare system; such integrated structures of care for mental health are exceptional for a low-income country.14–Reference Missmahl16 Several initiatives were also developed to establish culturally relevant mental health services for Afghans taking refuge in host countries. This paper provides a synthesis of the evidence on the main individual, cultural and structural factors pertaining to Afghan mental healthcare and psychosocial support. It identifies the main factors driving the epidemiology of poor mental health, culturally salient understandings of psychological distress, coping strategies and health-seeking behaviours, and interventions for better systems of mental healthcare. This allows us to reflect upon the daunting task of addressing mental health needs for Afghans, in ways that promote health, dignity and resilience, and ensure equity and sustainability within systems of care.

Method

Search strategy

Our review methodology was guided by the ‘Toolkit for Assessing Mental Health and Psychosocial Needs in Humanitarian Settings’.Reference Greene, Jordans, Kohrt, Ventevogel, Kirmayer and Hassan17,18 In 2022 (January to July), we searched both peer-reviewed and grey literature sources that focused on Afghan mental health, published from 1978 onward. We systematically searched for papers through Google Scholar, PTSDpubs (formerly PILOTS), PubMed and PsycINFO applying combinations of the following search terms (optimising the ‘AND’, ‘NOT’, ‘OR’ Boolean operators): ‘Afghan*’, ‘mental’, ‘health’, ‘psycho*’, ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘trauma’, ‘PTSD’, ‘help-seeking’, ‘support’, ‘refuge*’, ‘asylum’. The term ‘Afghan’ had to appear in titles, abstracts or key words as a primary condition of eligibility. Grey literature included unpublished reports produced by the Afghan government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) providing MHPSS services in Afghanistan, requested through email correspondence.

Thematic analysis

Two co-authors (Q.A. and P.V.) independently vetted all papers for inclusion, based on titles and abstracts. They then categorised papers with respect to methodology (e.g. historical, correlational, intervention and qualitative studies), sample and setting, measures and outcomes, study purpose and thematic content. The core themes structuring this paper were established inductively, through the careful grouping of studies based on their thematic content (e.g. child and adolescent mental health, suicide, substance misuse). Emerging lack of consensus, with respect to thematic structure, was resolved through consultation and email discussion with all other authors; for example, the author group discussed whether papers on community-based psychosocial programming were best grouped separately from, or together with, papers on psychiatric services and psychological treatment.

Results

Our search yielded 214 papers (n = 143 pertaining to Afghanistan, n = 71 pertaining to refugees). This included academic publications in peer-reviewed journals (n = 154), books (n = 16) or dissertations (n = 4); and grey literature comprising government documents (n = 7), reports by non-governmental organisations (n = 20) and publications by inter-government or donor organisations (n = 12). We present our results in two sections. The first is an overview of epidemiological and culturally specific data on Afghan mental health. The second focuses on systems of mental healthcare, community-based psychosocial support and psychological interventions.

Afghan mental health

Epidemiological studies and their limitations

Large-scale, epidemiological mental health surveys were only undertaken in Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001. Earlier studies had nonetheless highlighted important mental health issues. Thus, in the 1990s, Afghan mental health specialists had raised concern regarding war-related mental health needs.Reference Wardak, Wilson and Raphael19,Reference Dadfar and Marsella20 In 2000, women who resided in Taliban-controlled areas were found significantly more likely to report symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation and actual suicidal attempts compared with women residing in non-Taliban-controlled areas.Reference Amowitz, Heisler and Iacopino21 Symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were also high among Afghan women in Kabul and in refugee settings in Pakistan,Reference Rasekh, Bauer, Manos and Iacopino22 which was linked to war-related death and injury of family members, forced displacement and enduring poverty.

Population-based surveys, conducted in 2003, showed that self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD and poor social functioning were very common, particularly among women.Reference Cardozo, Bilukha, Crawford, Shaikh, Wolfe and Gerber23–Reference Scholte, Olff, Ventevogel, de Vries, Jansveld and Cardozo25 Gender-related vulnerability was also reported among those who used primary care services.Reference Seino, Takano, Mashal, Hemat and Nakamura26–Reference Wildt, Umanos, Khanzada, Saleh, Rahman and Zakowski29 In Eastern Afghanistan, a 2022 community-based survey identified a highly distressed population, with 53% of respondents indicating they often felt so hopeless that they did not want to carry on living, and 64% indicating they felt so angry that they often felt out of control.Reference van der Walt30 Among Kabul University students in 2021, in the aftermath of the fall of the Ashraf Ghani Government, 70% of respondents reported significant symptoms of PSTD and/or depression, and 39% indicated heightened suicide ideation/behaviour.Reference Naghavi, Afsharzada, Brailovskaia and Teismann31

These studies were based on self-reports with questionnaires that were not validated for culture and context. This raised questions regarding the validity of thresholds used to demarcate psychiatric disorders from psychological distress, and just as importantly, questions regarding the face validity and relevance of psychiatric symptoms and trauma reports for Afghan populations.Reference Bolton and Betancourt32 Subsequent clinical validation of a widely used screening tool, the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist-25, in Afghanistan and among Afghan refugees in Japan found only moderate agreement between the results of screening and clinical interviews.Reference Ichikawa, Nakahara and Wakai33,Reference Ventevogel, De Vries, Scholte, Shinwari, Faiz and Nassery34

The above studies must, therefore, be read with a great deal of caution: high prevalence estimates likely conflate mental disorders with psychosocial distress,Reference Ventevogel and Faiz35 whereas culturally grounded indicators may be more suited to assess severe mental distress.Reference Rasmussen, Ventevogel, Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick36 Indeed, the 2018 National Mental Health Survey, commissioned by the Afghan Government, found markedly lower prevalence estimates for adults (N = 4445), using a diagnostic standardised interview (the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form) rather than self-report screening questionnaires. In this probability survey by multistage sampling, 12-month prevalence of PTSD was 5.3%, major depressive episode was 11.7% and generalised anxiety disorder was 2.8%.Reference Kovess-Masfety, Keyes, Karam, Sabawoon and Sarwari37

Adult mental health

Studies in Afghanistan have documented. high levels of exposure to potentially traumatic events. For example, in the 2003 study by Scholte et al, 57% of adults surveyed had experienced more than eight potentially traumatic events over the past decade, including shortages of food, lack of access to medical treatment and lack of shelter.Reference Scholte, Olff, Ventevogel, de Vries, Jansveld and Cardozo25 However, the associations between trauma events and mental health symptoms are not always straightforward. For example, the 2003 study by Cardozo et al did not find significant associations between trauma exposure and PTSD symptom criteria, only with anxiety; this was attributed to extreme economic hardship elevating stress and anxiety, without associated PSTD.Reference Cardozo, Bilukha, Crawford, Shaikh, Wolfe and Gerber23 The point is important, and reiterated in many studies: among Afghans, mental health issues do not arise only from war-related violence. They arise from everyday stressors related to human insecurity, in the wake of poverty, forced displacement, the disruption of family and community support, and the loss of housing and livelihoods.Reference Missmahl16,Reference Miller, Omidian, Rasmussen, Yaqubi and Daudzai38–Reference Eggerman and Panter-Brick41

Gender differences in depression and anxiety are clearly pronounced in Afghanistan.Reference Miller, Omidian, Rasmussen, Yaqubi and Daudzai38,Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Gonzalez and Safdar42,Reference Razjouyan, Farokhi, Qaderi, Qaderi, Masoumi and Shah43 These are attributed to the systematic and institutional discrimination experienced by Afghan women in many parts of the countryReference Omidian and Miller44 including the system of purdah, a practice of strict gender segregation excluding women from public spaces.Reference de Jong45 Gender difference in mental health issues may also be related to the cultural ‘straitjacket’ governing the public expression of emotions, discouraging women to reveal forms of despair and men to show fear, grief or doubt, as this would bring shame on the family.Reference Ventevogel and Faiz35,Reference Omidian, Panter-Brick, Abramowitz and Panter-Brick46,Reference Chiovenda47

For young adults, studies have linked common symptoms of distress with higher education, ethnicity, income instability and reduced levels of hope and optimism with regard to one's own trajectory and the country's future.Reference Alemi, Stempel, Koga, Montgomery, Smith and Sandhu48 This may reflect a pervasive disillusionment with a national economy that cannot provide job opportunities for many university graduates. Indeed, a survey of a representative sample of Kabul University students in 2008 demonstrated that both men and women were frustrated by the conditions that led to widespread insecurity and prevented social advancement.Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Mojadidi and McDade49 Using biomarkers to measure individual-level stress (N = 161), this study confirmed the salience of family stressors for women's mental health and significant associations between psychological and physiological markers of well-being. Biomarker stress data demonstrated that, for Afghans, the gendered structure of everyday life had consequences for both stress physiology and mental health.

Child and adolescent mental health

Among children and youth, community-based surveys and ethnographic research have shown that family-level violence, more so than war-related violence, is an important driver of mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.Reference Catani, Schauer, Elbert, Missmahl, Bette and Neuner50–Reference Langer, Ahmad, Auge and Majidi52 In 2006–2007, a prospective study in Afghanistan and among refugees in Pakistan by Panter-Brick et al used stratified random sampling to survey adolescents, parents and teachers (N = 3014) to assess mental health, traumatic experiences and social functioning. It found that both war-related and family-level violence had demonstrable effects on the mental health of 11- to 16-year-old children.Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Gonzalez and Safdar42 It also demonstrated strong associations between caregiver and child mental health: 1 s.d. change in caregiver mental health was associated, at follow-up, with a 1.04-point change on child post-traumatic stress symptoms, equivalent to the predictive impact of a child's lifetime exposure to one or two trauma events, as well as a 0.65-point change in depressive symptoms, which was equivalent to two-thirds of the effect attributed to female gender.Reference Panter-Brick, Grimon and Eggerman53 The study also documented that trauma memories were malleable over time, presenting heterogeneous associations with post-traumatic distress. Because traumatic events were embedded in social experiences, being shaped by family and cultural narratives of suffering and resilience, trauma was best described as both a clinical and a social event. Cases of domestic violence were a case in point, being reported as trauma only when described as ‘senseless’ – beyond normative disciplinary violence, or stressful outbursts of violence triggered by insecure employment, housing or school difficulties.Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Gonzalez and Safdar42,Reference Panter-Brick, Grimon, Kalin and Eggerman51

Again, this cautions against simplifying assumptions linking trauma, war-related violence and mental health that elude consideration of family functioning or socioeconomic factors. For example, a 2013 survey of displaced 15- to 24-year-old youth (N = 2006) in Kabul reported that both everyday and militarised violence affected mental health,54 and 2016 interviews with 10- to 21-year-olds in Kabul, Kunduz and Balkh showed that violence had become a ‘normalised’ part of daily life-worlds, shaping almost all social interactions.Reference Langer, Ahmad, Auge and Majidi52 Harsh discipline is often related to a parent's own experience of family-level violence, as found in a study of women who stated witnessing their own mothers being physically abused and mentioning how they acted violently toward children when feeling distressed.Reference Ndungu, Jewkes, Ngcobo-Sithole, Chirwa and Gibbs55,Reference Allan, Najm, Fernandes and Allchin56 Even in schools, child-on-child violence has been linked to exposure to home-based violence.Reference Corboz, Hemat, Siddiq and Jewkes57

Data from after the fall of the Ghani Government, although scarce, point to a deterioration of the psychosocial well-being of children. A 2021 study of 10- to 12-year-olds in rural primary schools of Badakhshan, Ghazni and Takhar provinces, using culturally adapted measures of depression and anxiety, found that 52% of children suffered from depression, including 2.6% from severe forms. Almost all children showed some signs of anxiety, 23% severely so. In a sample of 376 high school children in Kabul, approximately half met the criteria for a probable diagnosis of PTSD (n = 194, 51.6%), depression (n = 184, 48.9%) or anxiety (n = 170, 45.2%).Reference Ahmadi, Jobson, Earnest, McAvoy, Musavi and Samim58

Gender-based violence

Gender-based violence is a known issue, but one difficult to report and address given the salience of family patriarchy and fear for social exclusion.Reference Tankink59 Afghanistan ranks highest among low- and middle-income countries in terms of past 12-month prevalence of physical, emotional and sexual violence.Reference Coll, Ewerling, García-Moreno, Hellwig and Barros60 Population-based surveys have found that close to half of Afghan women reported exposure to violence from their husbands.Reference Alemi, Stempel, Montgomery, Koga, Smith and Baek61,Reference Shinwari, Wilson, Abiodun and Shaikh62 Globally, Afghanistan is rated the worst place to be a woman or a girl.63

Although the literature linking gender-based violence and mental health is sparse, a recent population-based study argued that Afghan women carry the double burden of war-related and gender-based violence, leading to high lifetime suicidal attempts and risks of depression and anxiety.Reference Kovess-Masfety, Keyes, Karam, Sabawoon and Sarwari37 In Eastern Afghanistan, for example, key informants indicated massive distress among women, because of violence in their homes.Reference van der Walt30 Research with perpetrators of gender-based violence in Afghanistan is extremely rare. In a national survey, Afghan men indicated that wife-beating is acceptable, whereas overt aggression over family members is not, and that aggressive behaviour is enacted out of frustration when unable to fulfil societal expectations.Reference Echavez, Mosawi and Pilongo64 Mental health professionals working in Afghanistan have also argued that men use violence in the home to counter their feelings of powerlessness.Reference Missmahl16

Suicide

A systematic review on seven studies on suicide and self-harm, based on hospital admissions, has drawn attention to women's markedly elevated rates of suicidality and self-harm, mostly in the form of self-immolation.Reference Paiman and Khan65 In Afghanistan's 2017 National Mental Health Survey (N = 4474), 2.2% of adults reported suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months and 3.4% reported that they had, at least once in their life, attempted suicide, with women almost doubly at risk compared with men.Reference Sabawoon, Keyes, Karam and Kovess-Masfety66 Within samples of women with clinical mental health issues, suicidality is particularly high: a study that randomly sampled 117 patients in a mental health clinic in Herat, comprising mostly women with depression, showed that 78% had reported suicidal ideation and 30% had thought about poison and self-immolation.Reference Maniam, Mansouri, Azimi, Abdullah, Esmati, Sidi, Alfonso, Chandra and Schulze67 An analysis of 77 cases of self-immolation showed that half of the victims were young (16–19 years old); four out of five had died.Reference Raj, Gomez and Silverman68 As identified by relatives or survivors of self-immolation, precipitating events included a forced marriage (29%), a practice known as ‘bad’ in which girls are exchanged as brides to settle family or clan conflict (18%), or abuse from in-laws (16%). Most scholars relate the drivers of self-harm to household conflict and forms of violence against women.Reference Paiman, Ali, Asad and Syed69,Reference Aziz70 Some observers have argued that self-harm may best be perceived as a form of social protest against oppression, often related to arranged and forced marriages.Reference Billaud71

Substance use

Data from a drug use survey by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in Afghanistan have suggested exponential increases in heroin use among Afghan adults between 2005 and 2009,72,Reference Todd, Macdonald, Khoshnood, Mansoor, Eggerman and Panter-Brick73 leading to adult drug use rates that are more than twice the global average.Reference Schweinhart, Shamblen, Shepherd, Courser, Young and Morales74 Among 13- to 18-year-olds, a drug use survey in 2019 showed considerable use of illegal substances among secondary school students (14% for boys, 8.5% for girls). A new problem within Afghanistan is the use of methamphetamine: 1.3% of Afghan students reported that during the past year they had used methamphetamine in powder form or as tablets known as ‘tablet K’.75,76

In 2021, a survey by the International Medical Corps across northern and eastern regions of Afghanistan showed that men endorsed the use of narcotic drugs as a serious problem, and that community leaders identified addiction as linked to mental health issues.77 For its part, the Afghanistan National Urban Drug Use Study, which relied on analyses of hair, urine and saliva samples from 5236 people in 2187 randomly selected households, showed that one in 20 (5.6%) biological samples showed evidence of opioid use. From laboratory tests, the estimated prevalence of substance use was 7.2% in men and 3.1% in women.Reference Cottler, Ajinkya, Goldberger, Ghani, Martin and Hu78

Research on substance use is fraught with challenges. Studies have indicated that drug use is widespread for refugees displaced to Iran and Pakistan,Reference Naseh, Wagner, Abtahi, Potocky and Zahedi79 linked to feelings of loss, distress and boredom in Iran, and limited economic mobility in Pakistan.Reference Ezard, Oppenheimer, Burton, Schilperoord, Macdonald and Adelekan80 Afghans with substance use problems reported being widely stigmatised in Iran.Reference Deilamizade, Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, Mohammadian and Puyan81,Reference Ghasemi, Rajabi, Negarandeh, Vedadhir and Majdzadeh82 There are reports of Afghan women, struggling to balance livelihoods and childcare responsibilities in Pakistan, giving opium to children to keep them tranquil.Reference Ezard, Oppenheimer, Burton, Schilperoord, Macdonald and Adelekan80,Reference Ventevogel, Jordans, Eggerman, van Mierlo, Panter-Brick, Fernando and Ferrari83 For women, access to substance use services has been very low;Reference Schweinhart, Shamblen, Shepherd, Courser, Young and Morales74 heroin use often leads them to being disowned by their families because of the shame associated with addiction.Reference Berger84 Detoxification and addiction treatment programmes are underutilised among those who use injection drugs.Reference Todd, Stibich, Stanekzai, Rasuli, Bayan and Wardak85,Reference Mufti86

Afghan refugees

As expected, studies find high PTSD and depression symptoms among Afghans displaced to countries such as Iran,Reference Kalafi, Hagh-Shenas and Ostovar87 Pakistan,Reference Naeem, Mufti, Aub, Harioon, Saifi and Dagawal88,Reference Mufti, Naeem, Chaudry, Haroon, Saifi and Qureshi89 Turkey,Reference Kurt, Ventevogel, Ekhtiari, Ilkkursun, Ersahin and Akbiyik90 SerbiaReference Varvin, Vladisavljević, Jović and Sagbakken91 and high-income countries such as Australia,Reference Hamrah, Hoang, Mond, Pahlavanzade, Charkazi and Auckland92,Reference Hamrah, Hoang, Mond, Pahlavanzade, Charkazi and Auckland93 Canada,Reference Ahmad, Othman and Lou94 Germany,Reference Walther, Kröger, Tibubos, Ta, von Scheve and Schupp95 The NetherlandsReference Gerritsen, Bramsen, Deville, van Willigen, Hovens and van der Ploeg96,Reference Gernaat, Malwand, Laban, Komproe and de Jong97 and the USA.Reference Alemi, James, Siddiq and Montgomery98 Poor mental health lingers for long periods after resettlement,Reference Sulaiman-Hill and Thompson99 given that the associations between trauma exposure and clinical symptoms are moderated through the presence of ongoing stressors and loss of coping resources.Reference Schiess-Jokanovic, Knefel, Kantor, Weindl, Schäfer and Lueger-Schuster100 Post-resettlement stressors include a state of precarity with regards to residence status,Reference Lamkaddem, Essink-Bot, Deville, Gerritsen and Stronks101,Reference Rostami, Wells, Solaimani, Berle, Hadzi-Pavlovic and Silove102 loneliness,Reference Hamrah, Hoang, Mond, Pahlavanzade, Charkazi and Auckland93,Reference Brown103 acculturation difficulties,Reference Groen, Richters, Laban and Devillé104 unemployment, intergenerational conflicts,Reference Tankink59 gender role changes,Reference Alemi, James, Cruz, Zepeda and Racadio105,Reference Stempel, Sami, Koga, Alemi, Smith and Shirazi106 discrimination,Reference Alemi and Stempel107 education and inclusion.Reference Rosenberg, Leung, Harris, Abdullah, Rohbar and Brown108,Reference Vindevogel, Verelst, Song and Ventevoge109

Notably, in some settings, Afghan refugees and asylum seekers face important restrictions on their mobility, with migration detention having both short-term and long-term adverse psychological effects.Reference Ichikawa, Nakahara and Wakai110,Reference Steel, Momartin, Silove, Coello, Aroche and Tay111 For example, Afghans confined to camps on the Greek islands reported high levels of psychological stress, related to their powerlessness and pessimism regarding current and future prospects.Reference Eleftherakos, van den Boogaard, Barry, Severy, Kotsioni and Roland-Gosselin112,Reference Episkopou, Venables, Whitehouse, Eleftherakos, Zamatto and de Bartolome Gisbert113 Similarly, Afghan refugees and asylum seekers in Serbia and Norway have reported high levels of desperation and frustration, in the context of de-humanising experiences at the hands of legal systems.Reference Varvin, Vladisavljević, Jović and Sagbakken91 Asylum procedures aggravate mental health conditions and recovery; this includes the experience of Afghan adults and children taking refuge in high-income countries.Reference Rostami, Wells, Solaimani, Berle, Hadzi-Pavlovic and Silove102,Reference Drozdek, Kamperman, Tol, Knipscheer and Kleber114,Reference Bakker, Dagevos and Engbersen115 For example, a study among unaccompanied asylum-seeking Afghan children in the UK found that PTSD symptoms were associated with pre-migration traumatic events (cumulative stress) and living arrangement (foster care versus independent living).Reference Bronstein, Montgomery and Ott116 In Sweden, unaccompanied refugee minors had a higher prevalence of PTSD compared with Syrian and Iraqi children.Reference Solberg, Nissen, Vaez, Cauley, Eriksson and Saboonchi117

Culture and mental health

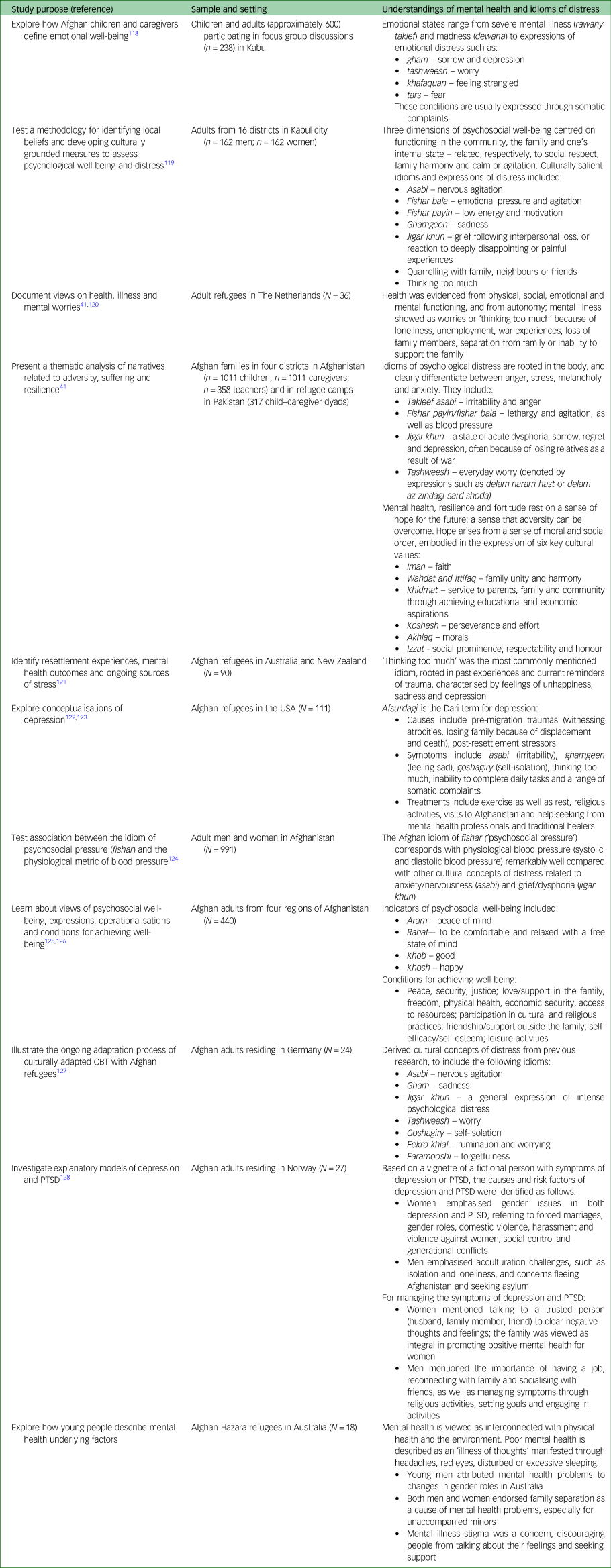

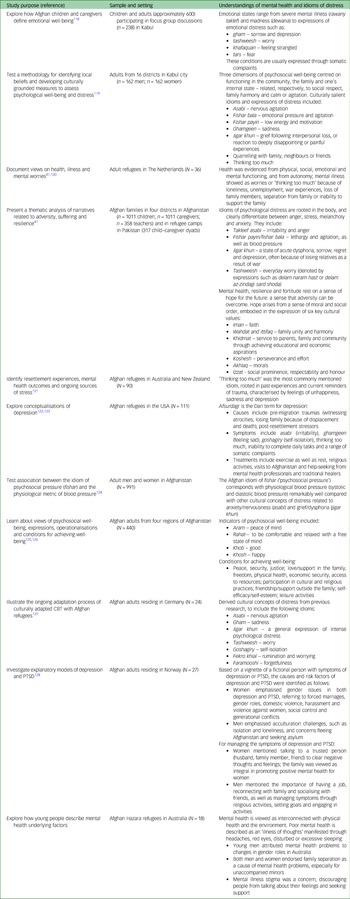

Our search returned 13 papers describing how Afghans understand different forms of mental health behaviour, psychological distress, well-being and resilience (Table 1). For example, De Berry et al's qualitative work in Kabul explored concepts of psychosocial well-being, providing a range of local idioms that subsequently informed support programmes for war-affected children in Afghanistan.Reference De Berry, Fazili, Farhad, Nasiry, Hashemi and Hakimi118 Miller et al's seminal work provided important insights into what it meant to be ‘doing well’ and ‘doing poorly’ psychologically.Reference Miller, Omidian, Quraishy, Quraishy, Nasiry and Nasiry119 Their study identified several indicators of poor mental health, some culturally specific, others known to Western psychiatry, and used these to construct a mental health screening tool: the Afghan Symptom Checklist. A subsequent study tested the extent to which Western and culturally specific conceptualisations of distress have unique physiological signatures, mapping on systolic and diastolic blood pressure.Reference Sancilio, Eggerman and Panter-Brick124 In turn, Eggerman and Panter-Brick's mixed-methods studyReference Eggerman and Panter-Brick41 documented the contexts in which Afghans articulated poor mental health and psychological distress, emphasising how Afghans saw clear links between health, lives and livelihoods: poor mental health was linked to war-related violence and the loss of loved ones, as well as the broken economy, inadequate shelter, poor education opportunities and insecure governance. The study also provided insights into how key cultural values (faith, family unity, service to the community, perseverance, morals and respectability) were the cultural backbone of psychosocial resilience in the face of ongoing adversities.

Table 1 Culturally salient understandings and idioms of mental health and psychosocial well-being, as narrated by Afghans

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Culturally salient expressions of depression include the concept of ‘thinking too much’,Reference Feldmann, Bensing and de Ruijter120,Reference Sulaiman-Hill and Thompson121,Reference Kananian, Starck and Stangier127 closely aligning with formal psychiatric classifications pertaining to temperament, cognition and functioning. Somatic complaints are prominent, in the form of headaches, chest pains, tension in the body or pins and needles. For example, ethnic Hazara refugees in Australia described poor mental health as an ‘illness of thoughts’, manifested through headaches, red eyes, disturbed sleeping or sleeping a lot.Reference Copolov and Knowles125 Specific Dari and Pashto idioms designate sorrow, pain and suffering, such as ‘gham’,Reference Alemi, James and Montgomery122,Reference Alemi, Weller, Montgomery and James123 through which women gain social respectability.Reference Grima129 Local explanations of PTSD symptoms have equated these to fear.Reference Brea Larios, Sandal, Guribye, Markova and Sam128,Reference Slewa-Younan, Guajardo, Yaser, Mond, Smith and Milosevic130,Reference Yaser, Slewa-Younan, Smith, Olson, Guajardo and Mond131 Finally, concepts of well-being, such as ‘aram’ (‘feeling psychologically and socially well’) and ‘rahat’ (‘feeling comfortable and relaxed, with free state of mind’), are closely linked to peace and security, strong family relationships, friendship/support outside family and engagement in religious/cultural practices.Reference Bragin, Akesson, Ahmady, Akbari, Ayubi and Faqiri126

Coping

Research on health-seeking behaviours has been limited. Afghans are reluctant to self-identify as having mental health issues,Reference Nine, Najm, Allan and Gronholm132 which puts a major stress upon families.Reference Oriya and Alekozai133 Afghans with persistent states of sadness may seek help from psychiatrists, ‘mullahs’ (religious leaders) or ‘tabibs’ (herbalists); take anti-depressants or turn to religious activities. Thus, in Afghanistan, mentally ill people are traditionally brought to mullahs, then to healing centres, often centred around the tomb of a holy man, such as the Sufi shrine of Mia Ali Baba.Reference van de Put134,Reference Ventevogel135 Early epidemiological research documented that people who feel ‘sad, worried or tense’Reference Scholte, Olff, Ventevogel, de Vries, Jansveld and Cardozo25 relied upon Islam as a source of faith and upon family support. In Kabul, young people sought help from both formal and informal sectors; namely, from primary care physicians, as well as from mullahs and tabibs.Reference Alemi, Montgomery, Smith, Stempel, Koga and Taylor136 One study reported that Afghan refugee youth in Iran resorted to imagination and fantasies to cope with exposure to extreme violence.Reference Chatty137 In Australia, asylum seekers have turned to general practitionersReference Slewa-Younan, Yaser, Guajardo, Mannan, Smith and Mond138,Reference Tomasi, Slewa-Younan, Narchal and Rioseco139 and mental health professionals,Reference Copolov and Knowles125 but have also drawn on faith and informal social networks for support.Reference Alemi, James, Cruz, Zepeda and Racadio105,Reference Kassam and Nanji140 Higher symptom severity was often the prompt for seeking care.Reference Kovess-Masfety, Karam, Keyes, Sabawoon and Sarwari141 One national survey (N = 5130 households) found that persons with disabilitiesReference Trani and Bakhshi142 experienced stigma from birth, because disabilities were attributed to a divine curse or the actions of a ‘jinn’.Reference Trani, Ballard and Pena143

Afghans have often been cited as a people living with singular resilience and fortitude among the ongoing challenges of war and socioeconomic adversity. As national and local structures of support were visibly broken, they came to rely on family and community, the only reliable social sources of support left to them.Reference Eggerman and Panter-Brick41 One case study illustrates what this means for a widowed mother of three, who experienced domestic violence.Reference Oriya144 She turned to her husband's first wife and her mother-in-law, then found other women who shared similar hardships; this calmed her feelings and showed she was not alone in her struggles. Webs of informal social support have also been reported for Afghan refugees living in the USA.Reference Lipson and Omidian145–Reference Omidian147 Most studies have emphasised that such ways of coping can be quickly undermined by social and economic isolation, and that research on mental health risk factors need to be balanced with in-depth understanding on cultural resources, social functioning, psychosocial well-being and resilience.

Mental healthcare and community-based interventions

Mental health services in Afghanistan

The government first initiated community-based mental health services during communist rule: in 1985, a Department of Mental Health was established within the Ministry of Public Health, with four community mental health centres in Kabul. In 1992, these care facilities were looted when the Soviet-backed government fell,Reference Rahimi and Azimi148 and throughout the civil war and Taliban regime, Afghanistan's rudimentary mental health system was severely disrupted.Reference van de Put134 A major step forward was taken in 1999, when a 3-month diploma course was initiated to train 20 medical practitioners in basic psychiatric practice;Reference Mohit, Saeed, Shahmohammadi, Bolhari, Bina and Gater149 it could not be sustained, given prevailing insecurity. By 2002, only two psychiatrists and a few dozen doctors were working within mental healthcare facilities, most of them with limited training.Reference Ventevogel, Azimi, Jalal and Kortmann150

In the early 2000s, the Afghan Government and donor communities made a strategic decision to contract out the reconstruction of Afghanistan's healthcare system to NGOs.Reference Palmer, Strong, Wali and Sondorp151 In Nangarhar province, HealthNet TPO, tasked with healthcare reconstruction, took steps to integrate mental health into basic healthcare, focusing on priority conditions such as depression, anxiety, psychosis and epilepsy.Reference Ventevogel and Kortmann152 This initiative resulted in significant increases in service utilisation for mental health, from fewer than 0.5% of all consultations in the healthcare system to around 5%.Reference Ventevogel, van de Put, Faiz, van Mierlo, Siddiqi and Komproe153 The programme was later rolled out to another six provinces, where, from 2005 to 2008, over 125 000 consultations related to mental health were registered, mostly for depression (66.6%), anxiety (14.9%), epilepsy (9.5%) and psychosis (4.3%), but also for intellectual disabilities (1.2%), substance use disorders (0.7%) and unexplained somatic and other complaints (2.8%).Reference Le Roy154

A key document in the reconstruction of the Afghan health system was the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS), published by the Afghan government in 2003.155 This document (Table 2) played a pivotal role in the remarkable increase in healthcare coverage in the first decade of reconstruction. It described the minimum services to be made available at primary health centres throughout the country, including community management of mental problems and health facility-based treatment of out-patients and in-patients with mental health conditions.Reference Newbrander, Ickx, Feroz and Stanekzai163 In 2005, a national coordinator for mental health in primary healthcare was appointed in the Afghanistan's Ministry of Health, subsequently establishing a mental health unit.Reference Ventevogel, Nassery, Azimi and Faiz164 Afghanistan's first national mental health strategy was thus explicitly designed to improve access to formal mental health services, moving away from hospital-based care toward integration into the primary care sector.160 This led to massive upscaling of efforts to train general health workers in identifying and managing the most prevalent mental health conditions.Reference Ventevogel, Sarwari, Missmahl, Faiz, Mäkilä and Queedes15,Reference Tirmizi, Khoja, Patten, Yousafzai, Scott and Durrani165–167 Up until 2018, NGOs trained almost 1000 physicians from all provinces through 12-day trainings in basic mental health, and over 1200 nurses and midwives received a 6-day basic mental health training, with curricula developed by the Afghan Ministry of Public Health.Footnote 1 The ‘mhGAP Intervention Guide’, a clinical tool to assist non-specialist health workers to identify and manage mental health conditions,168 was introduced on a smaller scale, in three provinces in 2013. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a national training of trainers in the WHO's Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP).Footnote 2

Table 2 Milestones in the development of mental health services in Afghanistan

Dr Sayed Azimi is an independent mental health specialist in Switzerland who served in various positions with the Ministry of Public Health and the World Health Organization in Afghanistan. Mariam Ahmady was until autumn 2022 Chairperson of the Department of Counseling at Kabul University in Afghanistan. Dr Mohammad Raza Stanikzai was National Programme Coordinator of Country Office for Afghanistan of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. MoPH, Ministry of Public Health; UNDCP, United Nations International Drugs Control Programme; WHO, World Health Organization.

A major innovation was to appoint psychosocial counsellors as mandatory staff in comprehensive health centres, following the revised BPHS in 2009.159,Reference Missmahl, Kluge, Bromand and Heinz169,Reference Sayed170 NGOs like Ipso and HealthNet TPO trained hundreds of men and women in the role of psychosocial counsellors.14,167 For example, Ipso established a 1-year training course and developed a standard curriculum for psychosocial counsellors with the Ministry of Public Health: this consisted of 3 months of intensive class-based training, followed by 9 months of practical work under supervision and two refresher training courses lasting 2 weeks. The training of this new cadre of health professionals became an accredited diploma programme of the Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences, under the Ministry of Public Health. Thus in 2019, around 750 psychosocial counsellors were embedded within the national health system.171 The Ghazanfar Institute also upgraded its curriculum to establish a 2-year diploma for health social counsellors, through which 190 people graduated up until 2021. Programmes in counselling psychology were also introduced into public universities by the Ministry of Higher Education,Reference Bragin and Akesson161,Reference Bragin, Akesson, Ahmady, Akbari, Ayubi and Faqiri172,Reference Berdondini, Grieve and Kaveh173 with 170 counselling psychologists (68% female) receiving a Bachelor's degree. Thus, in 2018, a Model Counselling Centre was established at Kabul University, playing a key role in improving students’ counselling and psychotherapeutic skills. Even after the regime change in 2021, the Department of Counseling continued to function, training 199 students (68% women) in gender-segregated classes as of July 2022.Footnote 3

Mental health treatment was also initiated in district hospitals and provincial hospitals. Before 2004, the secondary mental health system in Afghanistan was limited to one 60-bed national mental hospital in Kabul and some psychiatric wards in provincial hospitals.174 The inclusion of mental health services in a priority list of interventions for secondary care,158 in itself remarkable, led to the establishment of psychiatric wards in the five regional hospitals and in provincial hospitals, despite issues with staff retention and equipment.Footnote 4 The National Mental Health Strategy 2019–2023 strived for integration of mental health services into all 83 district hospitals and 27 provincial hospitals; five regional mental health wards provided in- and out-patient specialised services, including residency programmes for psychiatrists.162 In reality, however, most district hospitals and provincial hospitals did not provide mental healthcare.

Integrating mental health in public systems of care Afghanistan required overcoming major financial, human, infrastructural and information resource limitations.175 Major challenges pertained to adequate staffing, quality of care and on-the-job supervision, given that clinical supervisors were often unable to visit health centres because of transport and security risks. Population needs were high: from 2017 to 2022, the governmental health information system registered around 2 million mental health conditions in primary care per year, constituting around 4% of the total consultations in primary care.Footnote 5 But despite attempts to improve hospital conditions and strengthen staff capacity,176 hospitals remained poorly staffed, with patients held in substandard conditions and treatment largely limited to pharmacotherapy. A 2015 assessment identified serious gaps in service delivery and gross disregard for human rights. Patients were routinely exposed to forced treatment and physical restraint, enduring verbal, physical and emotional abuse.Reference Parwiz and Caldas de Almeida177

Despite all efforts, the mental health system in Afghanistan is far below acceptable levels of service provision. The number of psychiatrists increased from just two in 2002 to over 100 in 2019:171 as of mid-2019, there was approximately one psychiatrist and one psychologist per half-million population.178 Rural dwellers struggle to access services because of insecurity, distance to health facilities, travel costs, medication expenses and/or private doctor fees. Household expenditures for health services are high, and the country does not provide a social insurance scheme.179 Poverty, treatment costs, stigmatising beliefs and limited support are main barriers to the care of mental disorders.Reference Trani, Ballard, Bakhshi and Hovmand180

With respect to drug use, Afghanistan reportedly had 104 treatment centres, providing residential, out-patient and home-based services for about 30 000 clients annually; this is a small portion of the estimated 2.5 million Afghans with substance use disorder.Reference Shamblen, Courser, Young, Schweinhart, Shepherd and Morales181,182 One evaluation study found that intensive treatment (10 days of detox, with 30–45 days of in-patient treatment and 12 months of out-patient treatment) led to significant reductions in opiates and other drug usage.Reference Courser, Johnson, Abadi, Shamblen, Young and Thompson183 Thus use of opioids fell by 39% among 865 people, a year after treatment.Reference Shamblen, Courser, Young, Schweinhart, Shepherd and Morales181 However, such a comprehensive service is exceptional; in most cases, there is insufficient follow-up after detoxification, and many drug treatment centres report high rates of relapse,Footnote 6 especially in the absence of recovery support, such as motivational techniques associated with successful treatment completion.Reference Rasekh, Saw, Azimi, Kariya, Yamamoto and Hamajima184 Opioid agonist treatment, based on ongoing methadone treatment, is rare and politically sensitive, and the opioid agonist treatment centre established by Médecins du MondeReference Vogel, Tschakarjan, Maguet, Vandecasteele, Kinkel and Dürsteler-MacFarland185,Reference Maguet and Majeed186 has now closed. Since August 2021, 44 drug rehabilitation centres are known to be closed; others operate without sufficient funds for staff salaries and medical supplies. Of the 16 centres in Kabul, only four still provided services in 2022, given the halt in donor funding.182

Community-based initiatives

Many international organisations launched community-based psychosocial support programmes after the 2001 fall of the Taliban. Such programmes were rooted in socioecological models of well-being,Reference De Berry187–Reference De Berry and Hart191 recognising that local cultural practices, traditional resources and social support systems can help preserve psychosocial well-being and resilience; for example, Afghan women have strong traditions of narrative storytelling, which provides opportunities for psychological healing.Reference Mannell, Ahmad and Ahmad192 Such programmes understood that restoring capacities in families and communities to manage psychosocial issues is often more pressing than launching interventions based on clinical expertise. They also saw the need to develop interventions in close consultation with community stakeholders.Reference Kostelny, Boothby, Strang and Wessellls193 Community-based psychosocial initiatives thus often involved participatory workshops with community workers and school teachers, and where possible, drew upon local coping and healing traditions.Reference De Berry187 They also engaged with government structures to train Afghan professionals in social work and community development, propelling the Afghan Government, as part of the National Skills Development Program, to create national social work standards and curricula for social work education.Reference Bragin, Tosone, Ihrig, Mollere, Niazi and Mayel194

Some of these initiatives built upon earlier work with Afghan refugee communities in Pakistan. For instance, the psychosocial training programmes for Afghan teachers, developed by the International Rescue Committee in Peshawar's refugee camps, was moved into Afghanistan.Reference Omidian and Papadopoulos195,Reference Omidian196 War Child Holland used ‘community action planning’ in Herat to improve children's well-being through play in safe spaces and intergenerational collaboration.Reference Ventevogel, van Huuksloot, Kortmann, Prewitt Diaz, Srinivasa Murthy and Lakshminarayana197 HealthNet TPO used a ‘community systems strengthening’ approach aimed at empowering people in Afghan villages to restore social cohesion, rebuild community trust and create a responsive and supportive environment for those in need. Mullahs, teachers and other community members were considered equal partners in improving psychosocial well-being, and also women's exposure to domestic violence, in culturally relevant ways.Reference van Mierlo198

Rigorous evaluations of community-based psychosocial initiatives were hardly ever conducted, with the notable exception of those conducted by a coalition of international NGOs implementing child-focused psychosocial activities in 150 villages in Northern Afghanistan. These activities included the creation of ‘child-centred spaces’, offering non-formal education and the establishment of community-led ‘child well-being committees’, engaging children, adolescents and adults to identify child protection threats and livelihood initiatives.Reference Kostelny, Boothby, Strang and Wessellls193,Reference Wessells and Kostelny199 They also aimed to help war-affected children to re-socialise through playing and learning, in the context of peace promotion within Afghan society.Reference Snider and Triplehorn189 Evaluations showed a positive impact on school attendance, children's feelings of safety and inter-ethnic social interactions,Reference Loughry, Macmullin, Eyber, Ababe, Ager and Kostelny200 and reductions in aggressive behaviours were sustained a year later.201 One evaluation used a quasi-experimental framework to compare a stand-alone psychosocial intervention with a participatory water-sanitation intervention; interestingly, the latter had larger positive effects on child and adult well-being a year later.Reference Loughry, Macmullin, Eyber, Ababe, Ager and Kostelny200

‘Focusing’, a body-based mindfulness practice developed in the USA, was introduced in Afghanistan as a self-healing method outside clinical settings. The intervention aimed at helping people listen to each other and to themselves with kindness and positivity, and to understand how emotional reactions to events are intrinsically related to their body's protective responses. ‘Focusing’ was adapted to Afghan values, taking into account family structures and everyday stressors, using local language to describe the process of mindfulness and drawing from Persian and Afghan poetry.Reference Omidian and Lawrence202 This approach served to anchor community-based psychosocial support programmes with schoolteachers, vocational training groups and NGO staff in Afghanistan. Thus, from 2002 to 2008, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) worked with local partners and Kabul University to give eight student interns per year extensive training in psychosocial support and in ‘focusing’, with classroom learning and supervised field experiences. The 10-h programme was designed to support trauma recovery, resilience and conflict resolution in non-medical settings. Over a 6-year period, the AFSC recorded that 48 trainers delivered the psychosocial support training package to 3242 teachers (AFSC internal reports 2002–2009). External reviews found that the method was easily embraced by both literate and non-literate Afghans.Reference Frohböse203,Reference Mehta204 Major donors such as the United States Agency for International Development and the European Union, which funded the Reintegration Assistance and Development in Afghanistan programme, continued to fund such approaches until the 2021 regime change.205,206

Psychological interventions

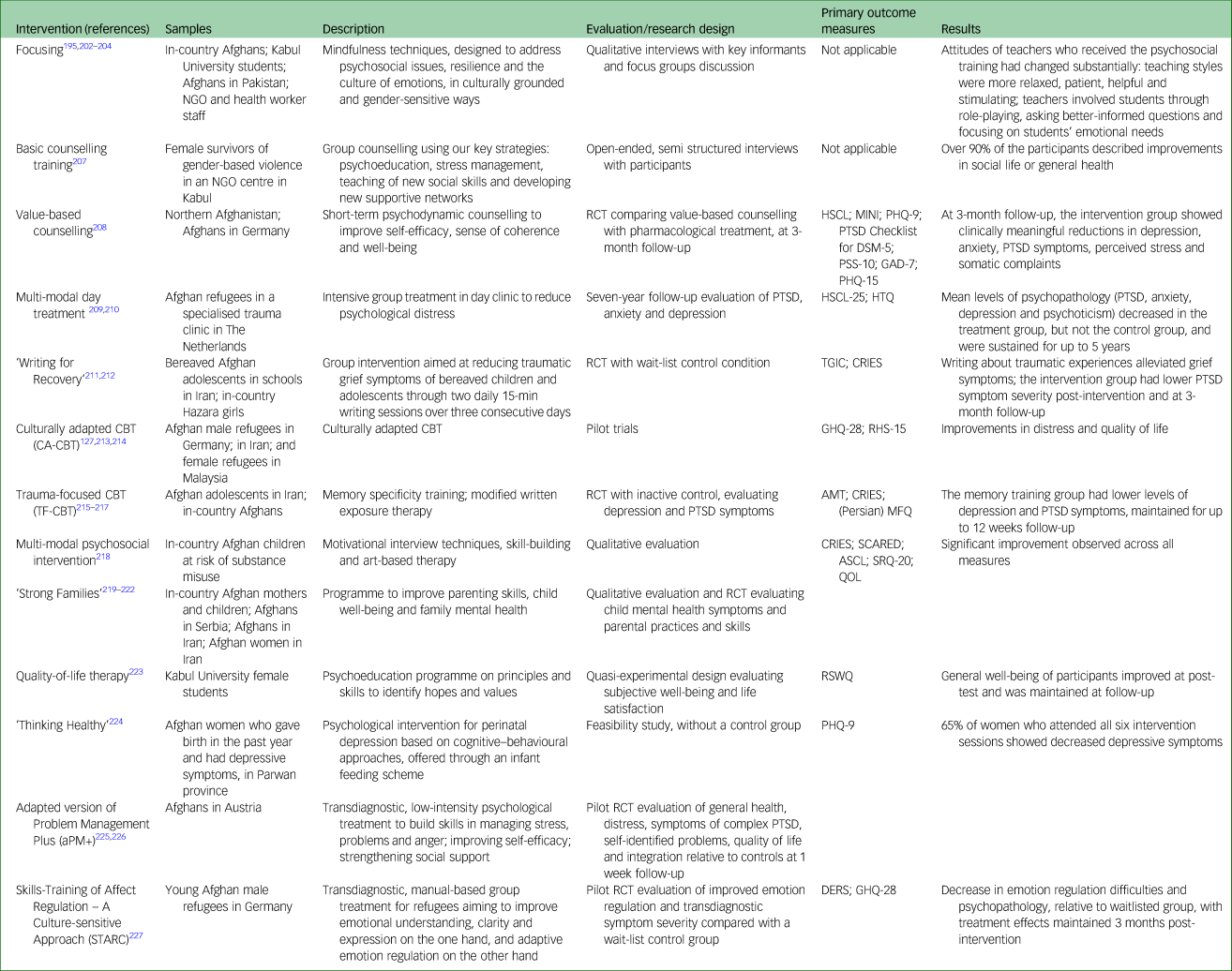

Our search returned 33 papers describing psychological interventions with Afghans, 24 of which assessed trial effectiveness or structured evaluations (Table 3).

Table 3 Psychological interventions with Afghan populations

NGO, non-governmental organisation; RCT, randomised controlled trial; HSCL, Hopkins Symptom Checklist; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-15, Patient Health Questionnaire-15; HSCL-25, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25; HTQ, Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; TGIC, Traumatic Grief Inventory for Children; CRIES, Child Revised Impact of Event Scale; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CA-CBT, culturally adapted cognitive–behavioural therapy; GHQ-28, General Health Questionnaire; RHS-15, Refugee Health Screener-15; TF-CBT, trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy; AMT, Autobiographical Memory Test; MFQ, Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; SCARED, Self-Report for Childhood Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; ASCL, Afghan Symptom Checklist; SRQ-20, Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; QOL, quality of life (ad hoc scale by researchers); RSWQ, Ryff Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale.

Value-based counselling

Within Afghanistan, the first randomised controlled trial of a psychological intervention compared a pharmacological treatment and value-based counselling (VBC), in a study conducted by Ayoughi et al among women in Northern Afghanistan.Reference Ayoughi, Missmahl, Weierstahl and Elbert208 VBC is a short-term psychodynamic intervention that aims to improve the sense of coherence and self-efficacy of clients in the course of a non-directive but carefully structured conversation.Reference Missmahl and Brugmann228 At 3-month follow-up, VBC clients reported clinically significant reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as fewer psychosocial stressors (e.g. family conflicts) and better coping responses. By contrast, symptom severity, number of stressors and coping mechanisms did not improve in patients receiving pharmacological treatment. Among Afghans in Germany, VBC clients showed a greater reduction of psychological symptoms, including depression, PTSD, perceived stress, anxiety, somatic complaints and daily functionality impairment, at post-test assessment relative to controls.Reference Orang, Missmahl, Thoele, Valensise, Brenner and Gardisi229 VBC was integral to the first training curriculum for psychosocial counsellors in Afghanistan's healthcare system.230

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

A number of studies have evaluated culturally adapted versions of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). For example, among war-bereaved Afghan adolescents in Iran, those in the experimental ‘Writing for Recovery’ group reported significant reductions in traumatic grief symptoms compared with controls;Reference Kalantari, Yule, Dyregrov, Neshatdoost and Ahmadi211 long-term effects were not assessed. Similarly, a study with Hazara adolescents found that both a written exposure therapy (five sessions) and trauma-focused CBT significantly reduced PTSD symptoms, compared with controls.Reference Ahmadi, Musavi, Samim, Sadeqi and Jobson212 Among bereaved Afghan adolescents in Iran, memory-specificity training reduced depression and PTSD symptoms at 12-week follow-up relative to controls.Reference Neshat-Doost, Dalgleish, Yule, Kalantari, Ahmadi and Dyregrov215,Reference Ahmadi, Kajbaf, Doost, Dalgleish, Jobson and Mosavi216 Culturally adapted CBT plus problem management (CA-CBT+), a resilience-focused intervention that utilises psychoeducation, problem-solving training, meditation and stretching exercises, was also shown to reduce psychological distress among 23 Afghan refugees in Germany at 1 year after intervention.Reference Kananian, Starck and Stangier127,Reference Kananian, Soltani, Hinton and Stangier213

The WHO has been instrumental in developing a number of scalable psychological interventions implemented with Afghans. For example, problem management plus (PM+) is a low-intensity, transdiagnostic psychological treatment aiming to enhance self-efficacy, social support and skills pertinent to coping with stress. It was adapted for Afghan refugees in Austria,Reference Knefel, Kantor, Weindl, Schiess-Jokanovic, Nicholson and Verginer225 and found to be effective in terms of reducing distress and PTSD symptoms and improving quality of life.Reference Knefel, Kantor, Weindl, Schiess-Jokanovic, Nicholson and Verginer226 It was also adapted for Afghans living in refugee camp settings in Greece,Reference Perera and Lavdas231 with ongoing programme evaluation.Reference Lavdas, Aravidou, Abu Salah, Marouga and Paveli232 Another WHO-endorsed intervention, Thinking Healthy, was implemented among rural Afghan women with postpartum depression: a feasibility study showed strong reduction of depressive symptoms for women who completed all sessions. However, managing expectations and treatment adherence proved a major challenge, as over half of the women did not return after the first session.Reference Tomlinson, Chaudhery, Ahmadzai, Rodríguez Gómez, Bizouerne and van Heyningen224 Lastly, a new transdiagnostic intervention, Skills-Training of Affect Regulation – A Culture-sensitive Approach (STARC), was shown to significantly improve self-reported difficulties in emotion regulation, transdiagnostic symptom severity and post-traumatic stress symptoms among young male refugees in Germany.Reference Koch, Ehring and Liedl227

Multimodal interventions

In one study, a multi-modal day-treatment programme was evaluated with survivors of torture among Afghan refugees in The Netherlands.Reference Drozdek, Kamperman, Bolwerk, Tol and Kleber209 Although causality cannot be inferred given the quasi-experimental design, symptoms were alleviated until 5 years after treatment, after which symptoms worsened but remained under baseline.Reference Drozdek, Kamperman, Tol, Knipscheer and Kleber210 Another evaluation study focused on motivational interviewing techniques, contingency management, skill-building education and art therapy techniques to prevent children at risk for substance use from declining into addictive behaviour; it showed promising results in a naturalistic study with children (N = 783) in Afghanistan.Reference Momand, Mattfeld, Morales, Ul Haq, Browne and O'Grady218

In turn, a retrospective study evaluated a psychosocial programme for survivors of gender-based violence in Afghanistan; it showed that 90% (n = 109) of women participating in the counselling groups described an improvement in their general health and social life.Reference Manneschmidt and Griese207 Another study evaluated the ‘Psychosocial Health Programme’ conducted in Kabul and Mazar-al-Sharif, with a representative sample (N = 296) of female survivors of gender-based violence: it found that participants reported increased self-esteem, self-efficacy and resilience, although the majority still had high symptom levels of PSTD and depression.Reference Huber, Zupancic and Huber233

Life skills training

‘Strong Families’, a programme designed to improve parenting skills as well as child well-being and family mental health, has shown promise in different contexts. For example, a pilot test in Afghanistan with 67 female caregivers and their children demonstrated clinically significant improvement in child mental health measures, along with improving parenting practices and family adjustment skills.Reference Haar, El-Khani, Molgaard and Maalouf219 The programme's feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness in improving child outcomes and parenting practices was also revealed for Afghan refugee families in SerbiaReference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf220 and Afghans in Iran.Reference Haar, El-Khani, Mostashari, Hafezi, Malek and Maalouf221 Based on qualitative data, El-Khani et al note that positive changes in participants were driven by improved caregiver–child communication and reduced harshness of parenting practices. This supports a theory of change whereby the change in parenting skills is a key mechanism for reducing and preventing future child behavioural and emotional problems.Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf220 Two other examples of life skills training are noteworthy. One was undertaken with 60 Afghan refugee women in Iran, showing improved social functioning and reduced mental health symptoms.Reference Shovazi, Mahmoodabadi and Salehzadeh222 Another engaged 40 female students at Kabul University, showing that quality-of-life training, as a therapeutic approach, improved subjective well-being and life satisfaction.Reference Ahmadi, Ayubi and Musavi223

Discussion

This article consolidates available evidence pertaining to the mental health of conflict-affected Afghans, with a view to provide useful resources for researchers, practitioners and policy makers working in the field of MHPSS. The human, social and economic toll that violence and forced displacement have taken on the mental health of the Afghan people is evident, both in-country and in refugee settings. Clearly, risks of mental health issues are disproportionately high for women, ethnic minorities, children and youth, people with disabilities and people using drugs. Within Afghanistan, needs are so dire that the United Nations warned that the deteriorating situation in the country and the limited access to services may drive a mental health crisis with long-term and unpredictable consequences.12

Based on our findings, we make four recommendations to address the mental health needs of Afghans in ways that can help promote equity and foster sustainable systems of care. First, interventions need to be culturally relevant, fitting the lived experience of Afghans and their conceptualisations of mental health and well-being. This requires intensive consultation, close engagement with local Afghan stakeholders and co-ownership of services. Sustainable programmes will be those that reflect cultural features that Afghans recognise as important, such as faith, perseverance and family relationships.Reference Omidian196,Reference Omidian234 It is important, for instance, to address the physical manifestations and social embeddedness of psychosocial distress, rather than medicalise common mental health symptoms. It is also important to structure interventions able to address gender disparities within the cultural logic of Afghan worldviews, and the social stressors that affect the lives of in-country and refugee Afghans. Specifically, people in Afghanistan face ongoing everyday stressors that are inextricably rooted in economic hardships, family conflicts and restrictive social policies that drain hope and aspirations. For their part, refugees, despite often showing remarkable agency and entrepreneurship in response to adversity, face the challenges of economic participation and social inclusion in host societies, with lives often marred by cultural bereavement, loss of social status, intergenerational conflicts and changes in gender roles.

Second, vigorous investment is needed to strengthen community-based psychosocial support and evidence-based psychological interventions. Fair and equitable access to psychosocial services must remain an important goal, with specific attention to the poor, women, ethnic minorities, and children and adolescents who are the next generation of Afghans. Because many mental health problems are engendered by family-related conflicts, many Afghans might be unable or reluctant to seek professional help, given resistance from family members who act as gatekeepers to healthcare access. It is thus essential to build upon approaches that sustain well-being, strengthen capacities of individuals and families to manage stress and effectively support each other, and can be facilitated at community-level without pathologising mental health issues. Many of such interventions have been shown to be feasibly implemented and yield important benefits. More research and evaluation work will be needed to build the evidence base for psychological interventions that are adapted to Afghan languages and contexts. This includes effectiveness research, detailing what works for whom, as well as implementation research, providing knowledge about how psychosocial interventions can be scaled up. Such work is best rooted in community-based participatory approaches that embrace local voices, to establish which MHPSS interventions ‘make sense’ and are feasible in the current context. Additionally, options need to be explored how mental health interventions can be integrated within broader initiatives targeting poverty alleviation, social cohesion, peacebuilding and reconciliation.

Third, core mental health services need to be maintained at a logical point of access, such as primary health centres and general hospitals, within Afghanistan. Urgent financial support is needed to avert the implosion of Afghanistan's health system, and mental health needs must not be overlooked. A minimally acceptable level of clinical psychiatric services, such as carefully described in key documents by the Ministry of Public Health,159,162 must be maintained within Afghanistan's overstretched and underfunded health system. This must be paired with initiatives to reduce barriers to healthcare access and to destigmatise mental illnesses through psychoeducation. The need to prevent and mitigate drug use, especially among at-risk youth, remains a matter of urgency, especially because HIV/AIDS is on the rise in Afghanistan and misconceptions about its spread are pervasive.

Finally, humanitarian efforts must invest in building sustainable systems of care, in which different approaches (community-based psychosocial work, psychotherapeutic interventions and clinical mental healthcare) connect and reinforce each other.Reference Weissbecker, Nic, Bhaird, Alves, Ventevogel and Willhoite235 Within Afghanistan, the remaining MHPSS professionals need to be engaged in capacity-building and supervisory roles. In countries hosting refugees and asylum seekers, the focus of service development must include the reinforcement of social support mechanisms and access to mental health services and community-based programmes; for example, by engaging Afghans themselves in service provision.

We recognise, with considerable concern, that the task of sustaining the legacy of MHPSS work is daunting within the current socio-political context of Afghanistan. There is no clear path or easy answer as to how the legacy of MHPSS work can be extended under the current Taliban rule. There are many challenges ahead; however, past initiatives overcame many more challenges, pertaining to political insecurity, shortages of health facilities and personnel, and equitable access to quality mental healthcare. Our recommendations stem from evidence synthesised in this thematic review. One important limitation of this review is that materials were not evaluated for quality or risk of bias; however, we were able to trace both peer-reviewed and grey literature sources, include multidisciplinary work from researchers and service providers, and encompass 40 years of research and practice.

This review of past achievements points to four ways of addressing the MHPSS needs of Afghans: building cultural relevance; investing in community-based psychosocial interventions and evidence-based psychological interventions; maintaining core mental health services at logical points of access and building integrated, sustainable systems of care. Addressing the needs of vulnerable groups will remain at the forefront of MHPSS efforts. Over time, Afghans have shown a remarkable capacity for innovative solutions in the context of adversity. We believe they will continue to do so, provided the international community, donor agencies, advocacy groups, academic institutions and other stakeholders continue investing resources into promoting and protecting the mental health and psychosocial well-being of the Afghan people.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anja Busse (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna, Austria), Tahani Elmobasher (UNICEF, Kabul, Afghanistan) and Karin Griese (Medica Mondiale, Cologne, Germany) for their input on earlier drafts of the manuscript. We also acknowledge the input of Mohammad Raza Stanikzai, National Programme Coordinator of UNODC Country Office for Afghanistan, who unexpectedly passed away in July 2022, and Bashir Ahmad Sarwari, Director of Mental Health in the Ministry of Public Health in Afghanistan from 2006 until his death in 2021.

Author contributions

The study was designed by Q.A. and P.V., who developed the search strategy, screened and analysed the data and drafted various versions of the manuscript. C.P.-B. and D.S. made important contributions in editing the manuscript. C.P.-B., S.O., M.A., A.Q.A., H.F., N.H., S.A.S.H., M.A.M., R.N., K.P., S.J.S., M.Z.S., Z.S., S.J.A., R.A., S.A., A.H., Z.M., A.M.S., M.B., W.K., M.L., K.E.M., I.M., P.A.O., D.S., J.-F.T and S.K.v.d.W. made substantial contributions by adding additional data, providing grey literature, revising the manuscript and interpreting the results. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for this research. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations they serve.

Declaration of interest

P.V. is member of the International Editorial Board of BJPsych Open. He was not involved in the decision-making process regarding this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.