Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by social communication/interaction challenges, restrictive and repetitive behaviour, inflexible behaviour patterns and atypical or excessive interests or hobbies.1 ASD is usually taken to capture a broad range of disorders, which has been previously referred to as Asperger's syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder and autism spectrum disorder. There is no universally accepted consensus on the terminology used to describe ASD. Here, we use identity-first language (‘autistic person/people’Reference Kenny, Hattersley, Molins, Buckley, Povey and Pellicano2) as this has been recommended by the stakeholders of the Substance use, Alcohol, and Behavioural Addictions in Autism partnership (SABA-AReference Sinclair, Aslan, Agabio, Anilkumar, Brosnan and Day3).

A recent UK study has suggested progressive increases in ASD diagnoses over time, with the greatest increase in adults and women.Reference Russell, Stapley, Newlove-Delgado, Salmon, White and Warren4 The apparent growth in the prevalence of ASD has been attributed to changes in diagnostic criteria,Reference King and Bearman5 reporting practices,Reference Hansen, Schendel and Parner6 and increased awareness.Reference Zeidan, Fombonne, Scorah, Ibrahim, Durkin and Saxena7 Despite suggested increases in ASD diagnoses, waiting time for assessment continues to rise across Europe.Reference Mendez, Oakley, Canitano, San José-Cáceres, Tinelli and Knapp8 Consequently, many autistic people continue to access healthcare services unrecognised and as incident rates increase,Reference Fountain, King and Bearman9,Reference Underwood, DelPozo-Banos, Frizzati, John and Hall10 so does the need to explore further co-occurring conditions to improve treatment outcomes.

Within ASD populations, research indicates alcohol is the most reported substance used.Reference Lai, Kassee, Besney, Bonato, Hull and Mandy11–Reference Isenberg, Woodward, Burke, Nowinski, Joshi and Wilens13 Previous reviews and meta-analyses of substance use disorder (SUD) in autistic populations reported a wide prevalence range of alcohol-use disorder (AUD; 0–16%), attributed to heterogeneity across study samples and the diagnostic procedures used.Reference Lai, Kassee, Besney, Bonato, Hull and Mandy11,Reference Lugo-Marín, Magán-Maganto, Rivero-Santana, Cuellar-Pompa, Alviani and Jenaro-Rio12,Reference Arnevik and Helverschou14,Reference Ressel, Thompson, Poulin, Normand, Fisher and Couture15 Several studies have found when compared with neurotypical peers, autistic adults report lower alcohol use and higher rates of abstinence.Reference Weir, Allison and Baron-Cohen16–Reference Fortuna, Robinson, Smith, Meccarello, Bullen and Nobis18 Further findings from two studies showed that the rate of alcohol use in autistic people increases with age.Reference Fortuna, Robinson, Smith, Meccarello, Bullen and Nobis18,Reference Kaltenegger, Doering, Gillberg, Wennberg and Lundström19

AUD is a spectrum disorder characterised by maladaptive patterns of alcohol use and related impairments of personal and social functioning that are clinically assessed as mild, moderate or severe.20 As criterion symptoms accumulate, the risk of harm and adverse psychosocial consequences increases.Reference Griswold, Fullman, Hawley, Arian, Zimsen and Tymeson21 Of all SUDs, AUD is the most prevalent within global populations, requiring targeted interventions and policies to reduce alcohol-related harm.Reference Degenhardt, Charlson, Ferrari, Santomauro, Erskine and Mantilla-Herrara22,Reference Bryazka, Reitsma, Griswold, Abate, Abbafati and Abbasi-Kangevari23 Of note, the language used to describe AUD may be stigmatising, leading to significant barriers to receiving or seeking support.Reference Hammarlund, Crapanzano, Luce, Mulligan and Ward24 Here, we extracted the same phraseology used in studies, but we omitted stigmatising labels such as addict, misuse and abuse within the main body.

Biopsychosocial factors of AUD and ASD

A greater understanding of both risk and protective factors in ASD could improve translational opportunities for research and clinical practice.Reference Szatmari25 Despite the estimates mentioned previously, the prevalence and nature of AUD among autistic people are underexplored.Reference Sinclair, Aslan, Agabio, Anilkumar, Brosnan and Day3,Reference Lai, Kassee, Besney, Bonato, Hull and Mandy11 From a biopsychosocial lens, identifying shared factors between conditions can offer avenues to promoting resilience and intervention of risk factors.

Typically, the developmental onset and course of both ASD and AUD are diverse. Early conceptualisations position ASD as emerging in childhood,Reference Ozonoff, Heung, Byrd, Hansen and Hertz-Picciotto26 while AUD routinely develops across the lifespan from adolescence and early adulthood.Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo and Salazar de Pablo27,Reference Deeken, Banaschewski, Kluge and Rapp28 Both conditions possess an element of genetic heritability.Reference Bai, Yip, Windham, Sourander, Francis and Yoffe29,Reference Verhulst, Neale and Kendler30 Two reviews found an overlap of neurological circuitry between ASD and SUD,Reference Rothwell31 as well as several independent studies which observed overlapping genes in the susceptibility to ASD or AUD.Reference Miles and McCarthy32 These findings suggest the possibility of shared genetic pathways between both conditions. However, the identification of specific risk variants for each remains inconclusive and emphasises consideration for epigenetic interactions.Reference Hall and Kelley33–Reference Hallmayer, Cleveland, Torres, Phillips, Cohen and Torigoe35

Several environmental factors are known to contribute to the development of AUD; including parental alcohol use and supply,Reference Sharmin, Kypri, Khanam, Wadolowski, Bruno and Mattick36 low prosocial behaviours,Reference Kendler, Gardner and Dick37 social norms,Reference Keyes, Schulenberg, O'Malley, Johnston, Bachman and Li38 peer substance use,Reference Yuen, Chan, Bruno, Clare, Mattick and Aiken39 and adverse childhood experiences.Reference Pilowsky, Keyes and Hasin40 Research has found some autistic people may have an equal or greater likelihood of experiencing traumatic events compared with neurotypical peers.Reference Hoover41–Reference Roberts, Koenen, Lyall, Robinson and Weisskopf43 This connection could be attributed to interpersonal victimisation and bullying, emotional dysregulation in processing traumatic stress, lack of support and social isolation common in ASD.Reference Hoover41–Reference Roberts, Koenen, Lyall, Robinson and Weisskopf43 Exposure to traumatic events, as a common factor for both ASD and AUD, may increase the overall risk of harmful alcohol use, whereas social capital, referring to the level of community attachment, closeness and supportiveness experienced by an individual, has the potential to reduce the risk of alcohol use.Reference Bryden, Roberts, Petticrew and McKee44 However, as mentioned previously, social isolation and lack of support are common in autistic people, presenting social capital as a possible area of vulnerability.

Characteristic features of ASD may be protective, influencing how an autistic person interacts with their environment. For example, developmental and communication challenges, as well as unsettled peer relationships in ASD adolescents, were negatively associated with alcohol and substance use.Reference Santosh and Mijovic45 In addition, certain factors such as parental involvement, household rules and monitoring can limit the availability and opportunity for alcohol use among autistic individuals, thus reducing the risk of developing AUD.Reference Yuen, Chan, Bruno, Clare, Mattick and Aiken39,Reference Ryan, Jorm and Lubman46

Bowri et alReference Bowri, Hull, Allison, Smith, Baron-Cohen and Lai17 examined factors associated with alcohol use within a high-functioning community sample of autistic adults. Dividing the sample into three groups by alcohol use, non-drinkers and hazardous drinking patterns were predictors for higher scores of autistic traits, depression, social anxiety and generalised anxiety, in comparison with non-hazardous drinkers. Non-hazardous drinkers reported the highest scores of well-being among the three groups, whereas hazardous use was associated with a higher frequency of co-occurring psychiatric conditions. However, these findings did not distinguish whether alcohol use acts as a protective factor against co-occurring psychiatric conditions or if reduced co-occurring conditions led to less harmful alcohol use.

Antecedents to alcohol use have focused on positive and negative motivations for use.Reference Brosnan and Adams47–Reference Rothman, Graham Holmes, Brooks, Krauss and Caplan49 Social facilitation, mood enhancement, symptom management, coping mechanisms for difficulties such as social anxiety, sensation seeking and ‘self-medication’ of sensory processing difficulties are themes positively associated with alcohol use.Reference Weir, Allison and Baron-Cohen16,Reference Brosnan and Adams47–Reference Pijnenburg, Kaplun, de Haan, Janecka, Smith and Reichenberg51 In contrast, factors such as fear of addiction, disinhibition, olfactory sensitivity and decreased access to alcohol limit the risk and decrease motivation for alcohol use in ASD populations.Reference Bowri, Hull, Allison, Smith, Baron-Cohen and Lai17,Reference Brosnan and Adams47,Reference Ashwin, Chapman, Howells, Rhydderch, Walker and Baron-Cohen52 Given the diverse levels of functioning and severity, inherent within the spectrum of both ASD and AUD, current research lacks a validated measure that simultaneously captures elements of both conditions. This absence of standardisation across studies impairs the ability to establish consistent conclusions from findings.Reference Sinclair, Aslan, Agabio, Anilkumar, Brosnan and Day3 Overall, there is a greater need to increase screening and prevention, and to reduce barriers to support for autistic people with AUD.Reference Brosnan and Adams47,Reference Adhia, Bair-Merritt, Broder-Fingert, Nunez Pepen, Suarez-Rocha and Rothman53–Reference Lalanne, Weiner, Trojak, Berna and Bertschy55

Current review

The Substance use, Alcohol, and Behavioural Addictions in Autism partnership (SABA-A), funded by the Society for the Study of Addiction, brought together a range of experts to identify key policy, research and clinical practice questions for ASD and addiction. In 2023, the project published the top ten priorities, outlining the most urgent issues impacting the lives of autistic individuals with substance use, problematic alcohol use or behavioural addictions.Reference Sinclair, Aslan, Agabio, Anilkumar, Brosnan and Day3 The highest-ranked priority was the identification and prevention of specific triggers, risk factors and facilitators of substance, alcohol or behavioural addictions in autistic people. Additional priorities included enhancing awareness, reducing stigma, adaptations to current approaches, how other conditions or traits impact the development and maintenance of addiction and differences in vulnerability between autistic and non-autistic populations. SABA-A has published one review on ASD and gambling and the current review explored ASD and alcohol use.Reference Chamberlain, Aslan, Quinn, Anilkumar, Robinson and Grant56

Existing reviews have generally focused on SUD, rather than exclusively on AUD. Different substances can serve different purposes for autistic adults, and given that alcohol use is common within ASD populations, it is of interest that there is limited information on how ASD and AUD present in clinical services.

Accordingly, our aim was to:

(1) systematically identify and collate findings from studies which have examined the association between AUD and ASD;

(2) explore the current knowledge of clinical samples on aetiology, including biological, psychological, social and environmental risk factors associated with alcohol use among autistic people; and implications, including the protective factors and consequences of co-occurring alcohol use in autistic people;

(3) identify priority research questions and offer recommendations for policy and clinical practice.

Method

Protocol registration

This was a pre-registered systematic review. The protocol was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 31 May 2023 (identifier CRD42023430291).

Design and search strategy

We conducted a search of the extant literature using five databases: CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsychInfo and Global Health. The search string consisted of: ((ASD) OR (Autis*) OR (Asperger*) OR (ASC) OR (PDD) OR (Pervasive Developmental Disorder) OR (Neurodevelopmental) OR (Kanner) OR (Developmental Disabilities / OR Autism Spectrum Disorders / OR Child Developmental Disorders [MeSH Major Topic])) AND (Alcohol*) OR (Alcohol addiction) OR (Alcohol misuse) OR (Alcohol dependen*) OR (Drinking) OR (Alcoholism / OR Alcohol abuse / OR Alcohol Use Disorder / OR Alcohol related disorders [MeSH Major Topic])). This string was adapted from an initial scope conducted by one of the authors (B.A.) and finalised with current authors.

The search was completed as planned with the exception at full-text screening to narrow the search to clinical samples only. Clinical samples were defined as participants recruited from healthcare settings or patient register databases. Given the heterogeneity of existing literature, this approach was taken to provide future clinical services and research recommendations as a meta-analysis would not be feasible at this stage. The search was repeated in August 2023 to identify any additional papers since the initial search in May 2023. This review adhered to narrative synthesis and PRISMA guidelines (see Supplementary material for checklist).Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow57,Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers58

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Primary inclusion required studies to explore broadly both ASD and alcohol use in a clinical setting or population. Studies that measured autistic traits were also included. We applied no limits on the date of publication or age of participants, accounting for potential longitudinal studies. Both qualitative and quantitative articles were included to capture reported life experiences alongside statistical inferences and associations between ASD and alcohol use. Included studies were required to be peer reviewed and published in English. We excluded studies of other reviews, meta-analyses, studies with an ASD sample of less than five, genome-wide association studies, book chapters and grey literature.

Data extraction and synthesis

A narrative synthesis was the preferred method of analysis as the literature is limited. Articles were initially screened by title and abstract, using the criteria specified, before retrieval for full-text review. Where studies did not solely focus on ASD and alcohol use, only related data were extracted. The first data extraction took place on 16 June 2023 and final data extraction on 18 August 2023, following the repeated search. Two raters (W.B., V.P.) were used at both steps of the screening process and quality appraisal. Any discrepancies were discussed among the authors until a consensus was reached. The overall approach was guided by the Popay et alReference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers58 framework for narrative synthesis. Tabulation was used to infer similarities across studies, and themes were grouped across aetiological factors and potential implications of ASD and alcohol use. The summary of findings is presented as a concept map, to capture key themes and inform the third aim, identifying priority areas and recommendations.Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers58

Quality assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMATReference Hong, Gonzalez-Reyes and Pluye59) was used to assess the methodological quality of selected studies. Each study was evaluated by design and rated across five criteria, individual to each study design (yes, 1; no, 0), with an overall quality score calculated as a percentage of total criteria met (presented in Table 1Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo and Dagenais60). We did not set a minimum threshold for quality criteria and, therefore, did not exclude any studies. Full quality description can be found (Supplementary Table 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2024.824).

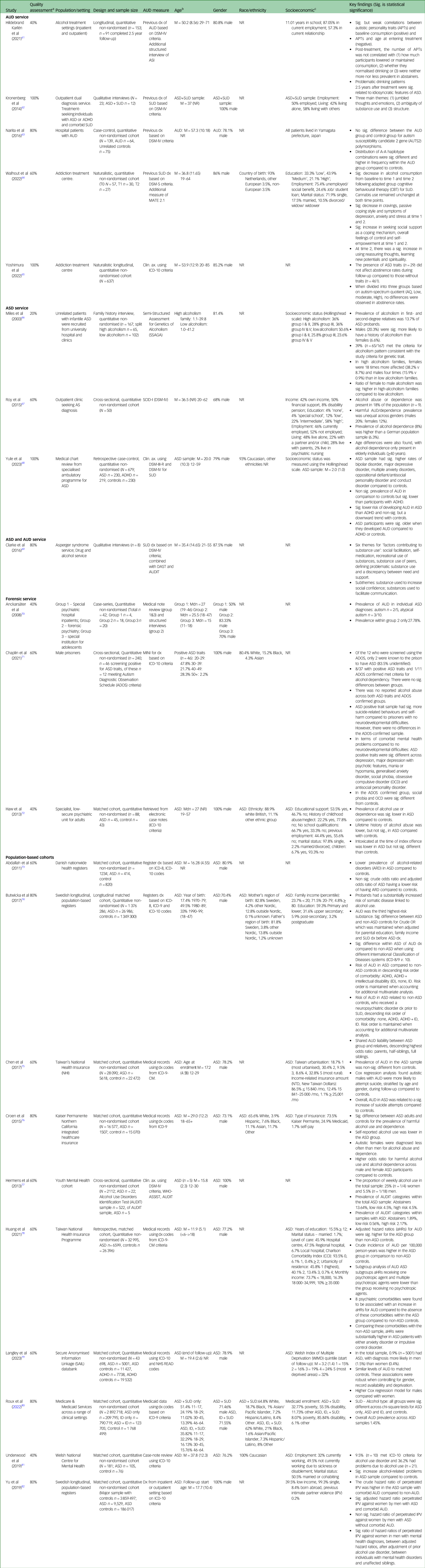

Table 1 Summary of studies included in the review

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; aHRs, adjusted hazard ratios; ARD, alcohol-related disorders; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AUD, alcohol-use disorder; AUTS2, autism susceptibility candidate 2 gene; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; Clin ax., clinical assessment; dx, diagnosis; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; ID, intellectual disability; M, mean; Mdn, median; NHI, national health insurance; NR, not reported; NTD, New Taiwan Dollar; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; SUD, substance-use disorder; WIMD, Welsh index of multiple deprivation.

Measures: ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule,Reference Cruz, Zubizarreta, Costa, Araújo, Martinho and Tubío-Fungueiriño83 adapted for prison use (89); AQ, autism-spectrum quotient (90); AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (87); CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index (91); Hollingshead scale, Hollingshead four factor index of social status (92); Taiwan urbanisation (93).

a. Quality assessment summarised by Mixed-Methods Appraisal ToolReference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers58,Reference Hong, Gonzalez-Reyes and Pluye59 total domain score. Percentage of quality criteria met are presented as star (*) ratings: *****, 100%, ****, 80%, ***, 60%, **, 40%, *, 20%.

b. Age is reported in years. Mean, (s.d.) and (range) reported where available.

c. Socioeconomic variables reported for ASD samples only where available. In absence, whole sample characteristics were reported. Variables include: education, employment, income, living arrangement, marital status, social support.

Results

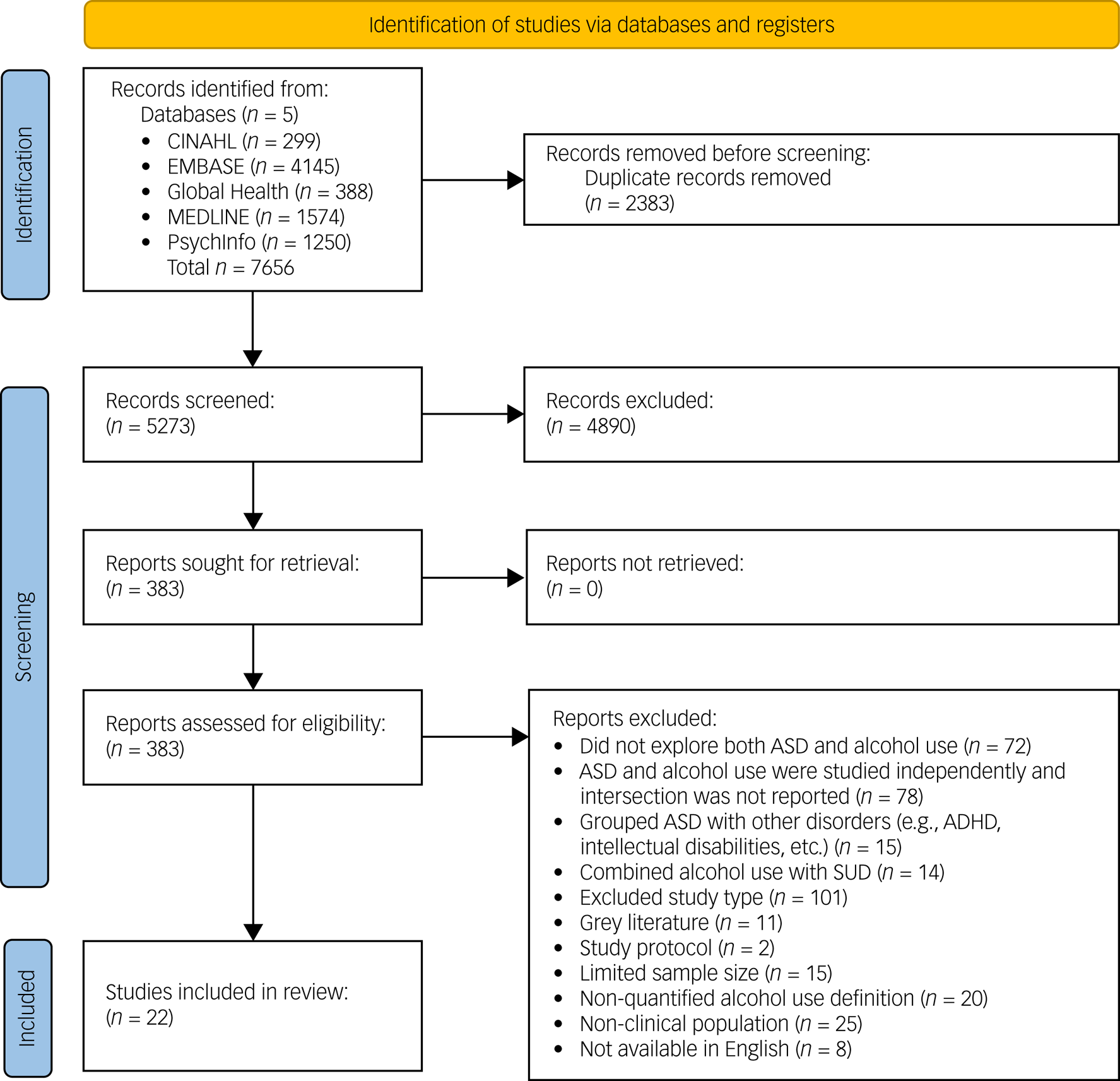

Twenty-two studies were included in the final review following the full-text screening of 383 articles (Fig. 1). Full study characteristics and a summary of individual findings are presented in Table 1. Detailed findings are reported below, and the data are synthesised into main components for aetiological risk factors and implications for co-occurring AUD in ASD in Box 1 as a concept map.Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers58 Four components of biological, psychological and social/environmental aetiological risk factors emerged alongside ten potential implications of co-occurring AUD in ASD.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; SUD, substance-use disorder.

Study characteristics

The publication year of included studies ranged from 2003 to 2023, with 45% of studies being published in the past 5 years (2019 to 2023). Studies were primarily conducted in European countries (n = 13), followed by the USA (n = 4), Japan (n = 2), Taiwan (n = 2) and Australia (n = 1). Study designs consisted of 20 quantitative (case-control n = 12, cross-sectional n = 5 and cohort studies n = 3) and two qualitative (interviews n = 2). Overall, samples were derived from a range of settings: drug and alcohol services (n = 5), ASD services (n = 3), a combination of both ASD/AUD services (n = 1), forensic (n = 3) and large, population-based registers (n = 10).

Quality appraisal

Overall, the average quality score of included studies was 66%, with the majority of studies 60% or above (n = 17). Studies that scored below 60% were retained due to limited available literature. The main quality issues within clinical settings were insufficient descriptions of study samples, utilisation of non-validated measures and absence of controls for confounding variables. In large population-based studies, diagnoses were primarily sourced from medical records, with a large proportion of missing data, and potential recruitment bias within samples due, for example, to paid healthcare insurance.

Participant characteristics

A total of 750 ASD participants were represented from clinical settings and 389 281 from large population registers. The pooled mean of ASD gender was 83.4% male. The ages of included participants ranged from 1.1 years to 85 years, with a median of mean 32.2 years (s.d. = 14.58) reported by 16 (72.7%) studies. Of studies that reported socioeconomic status (count 16) and race and ethnicity (count 8), records were incompatible for comparison across categories. For studies that reported demographics, participants were primarily White/Caucasian, achieved primary and secondary education qualifications, were unemployed, single, possessed lower socioeconomic scores and lived in urbanised areas (see Table 1 for individual breakdown).

Prevalence and risk

Excluding studies with exclusive ASD-AUD samples (i.e. samples that only included individuals with both by deliberate design), prevalence in clinical settings ranged from 6.7% to 39%; while in large population-based registers, the rate varied between 0.7% and 9.5%. Pooled prevalence was higher for clinical settings (121/750, 16.13%) than large population registers (6124/389 281, 1.57%).

In large population-based registers, the associated average risk of AUD within ASD patients compared with non-ASD controls, varied significantly. Two studies suggested a decreased AUD risk,Reference Croen, Zerbo, Qian, Massolo, Rich and Sidney76,Reference Cruz, Zubizarreta, Costa, Araújo, Martinho and Tubío-Fungueiriño83 three studies found similar or no difference in AUD risk,Reference Abdallah, Greaves-Lord, Grove, Norgaard-Pedersen, Hougaard and Mortensen73,Reference Chen, Pan, Lan, Hsu, Huang and Su75,Reference Langley, Pozo-Banos, Daalsgard, Paranjothy, Riglin and John79 and four studies indicated increased AUD risk.Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74,Reference Huang, Yang, Chien, Yeh, Chung and Tsai78,Reference Roux, Tao, Marcus, Lushin and Shea80

Aetiological risk factors

Risk factors involved in the development of AUD in ASD included genetics, co-occuring conditions, gender and age.

Three studies of varying quality found evidence for a genetic pattern and increasing average risk between ASD and AUD.Reference Narita, Nagahori, Nishizawa, Yoshihara, Kawai and Ikeda63,Reference Miles, Takahashi, Haber and Hadden66,Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 As both conditions are heterogeneous in origin, a lack of genetic specificity within the literature can only conclude an overall association. The indicated risk of AUD is substantially compounded by co-occurring disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Reference Yule, DiSalvo, Biederman, Wilens, Dallenbach and Taubin68,Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74,Reference Huang, Yang, Chien, Yeh, Chung and Tsai78 However, in comparison with ADHD alone, ASD was associated with a lower average risk of AUD.Reference Yule, DiSalvo, Biederman, Wilens, Dallenbach and Taubin68 Furthermore, when compared with non-ASD controls, ASD-AUD patients present with higher occurrences of anxiety disorders accentuating the complexity between disorders.Reference Chaplin, McCarthy, Allely, Forrester, Underwood and Hayward71,Reference Huang, Yang, Chien, Yeh, Chung and Tsai78 Gender differences contribute to this complexity, as autistic women were underrepresented and diagnosed less frequently than autistic men in included studies.Reference Miles, Takahashi, Haber and Hadden66,Reference Croen, Zerbo, Qian, Massolo, Rich and Sidney76,Reference Langley, Pozo-Banos, Daalsgard, Paranjothy, Riglin and John79 Yet findings present a higher risk for AUD in autistic women, indicating a nuanced relationship given the unequal distribution across samples and overlapping confidence intervals with male counterparts, which requires further study. In addition, there was an emerging pattern of alcohol use developing in older ASD patients when compared with controls.Reference Roy, Prox-Vagedes, Ohlmeier and Dillo67,Reference Yule, DiSalvo, Biederman, Wilens, Dallenbach and Taubin68

Two qualitative studies explored the development and everyday life consequences of SUD in ASD.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69 Emerging themes indicated two interrelated alcohol use coping motives: self-medication and social facilitation. Proactive strategies position alcohol use as a means to self-medicate symptoms associated with cognitive and emotional distress, as well as idiosyncratic features of ASD such as sensitivity to sensory processes.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69 Reactive strategies occur in the context of social situations, to facilitate interactions or cope with associated negative appraisals. ASD patients described the inability to express themselves and anticipated social rejection, leading to feelings of loneliness and social exclusion.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69 Through alcohol use, insecurities and oversensitivity can be mitigated by feeling more confident and comfortable in social situations.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69 This reinforces the use of alcohol due to elevated mood, social gains, connection and alleviation of social anxiety.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69

Implications of alcohol use

From this review, the literature suggests a continued pattern of alcohol use could impact general functioning and increased harmful experiences, such as somatic disease, intimate partner violence and suicide attempts.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74,Reference Chen, Pan, Lan, Hsu, Huang and Su75,Reference Yu, Nevado-Holgado, Molero, D'Onofrio, Larsson and Howard82 Further analysis of suicide attempts, stratified by age and gender, found only autistic men had a significant increase in average risk, compared with controls, lending further support to gender differences.Reference Chen, Pan, Lan, Hsu, Huang and Su75 The included study of intimate partner violence only investigated the perpetration against women by men with comorbid ASD and AUD. Hazard ratios of engaging in intimate partner violence against women by men were significantly greater in autistic people with comorbid AUD.Reference Yu, Nevado-Holgado, Molero, D'Onofrio, Larsson and Howard82

The consequences of alcohol-related problems can be maintained by specific ASD traits.Reference Hildebrand Karlen, Stalheim, Berglund and Wennberg61 A series of exploratory Pearson chi-square tests found traits of rigidity, social avoidance and withdrawal, were significantly related to harmful drinking patterns. For example, rigidity in thought could create a barrier to implementing lifestyle change. The authors questioned whether these specific traits were indicative of long-term difficulties, such as anxiety and inflexibility to adapt to social cues or the overlap of these traits in the spectrum of alcohol use; although ASD traits were not found to be related to rates of abstinence at follow-up.Reference Hildebrand Karlen, Stalheim, Berglund and Wennberg61,Reference Yoshimura, Matsushita, Kimura, Yoneda, Maesato and Yokoyama65 If certain characteristics of ASD sustain harmful patterns of alcohol use, current intervention methods may not adequately address patient needs, and greater accommodation for ASD traits may yield greater outcomes.Reference Hildebrand Karlen, Stalheim, Berglund and Wennberg61 As such, adapted ASD-AUD treatment, with a focus on core ASD symptoms, social skills and ASD-related stress, presented promising results requiring further study.Reference Walhout, van Zanten, DeFuentes-Merillas, Sonneborn and Bosma64

Box 1 Concept map of findings for alcohol use in clinical, autistic populations. ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AUD, alcohol-use disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Potential protective factors of developing AUD in ASD included psychotropic medication use and a prior diagnosis of ASD. Huang et alReference Huang, Yang, Chien, Yeh, Chung and Tsai78 found a reduction in overall AUD average risk if autistic patients had received one or multiple psychotropic medications, even in the context of additional co-occurring disorders. Psychotropic medication was classified as antidepressants, second-generation antipsychotics and mood stabilisers. The risk of AUD was decreased among patients who had received a prior diagnosis of ASD, for both patients with no co-occurring conditions and co-occurring ADHD.Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 However, one forensic study found the majority of cases that met ASD diagnostic criteria, were previously unknown to providers.Reference Chaplin, McCarthy, Allely, Forrester, Underwood and Hayward71

Discussion

This narrative systematic review aimed to identify relevant clinical studies, explore the aetiology and implications of alcohol use in ASD and suggest future research, policy and clinical recommendations. The final review included 22 studies, extracting data from healthcare settings and large, population-based registers. The findings of this review stress the variable nature of studies investigating AUD in ASD. Due to divergent quality and heterogeneous parameters, our overall findings are speculative.

Of the included studies, the prevalence of AUD in ASD appears to range between 1.6% in large population registers and 16.1% in clinical settings. Within global populations, irrespective of neurodiversity status, the lifetime prevalence of AUD is estimated to be 8.6%.Reference Glantz, Bharat, Degenhardt, Sampson, Scott and Lim84 This is substantially greater than the rate found in this review, potentially supporting the evidence that autistic populations generally report lower rates of alcohol use.Reference Weir, Allison and Baron-Cohen16–Reference Fortuna, Robinson, Smith, Meccarello, Bullen and Nobis18 This is further compounded given the low global prevalence rates of ASD,Reference Zeidan, Fombonne, Scorah, Ibrahim, Durkin and Saxena7 despite the recent suggested increase in ASD diagnoses.Reference Russell, Stapley, Newlove-Delgado, Salmon, White and Warren4 With regard to clinical settings, the observed prevalence in this review is greater than that of one study (11.8%), which compared rates of AUD in European primary care to a general population.Reference Manthey, Gual, Jakubczyk, Pieper, Probst and Struzzo85 However, Manthey et alReference Manthey, Gual, Jakubczyk, Pieper, Probst and Struzzo85 did not differentiate for neurodiversity status. It is possible AUD is exacerbated by ASD symptoms, and given the higher observed rate in this review, screening within clinical services is important to explore the intersection between disorders and improve the precision of prevalence rates.

This review identified four possible risk factors for the development of AUD in ASD: age, co-occurring conditions, gender and genetics. Based on the broader literature and this review, both conditions may share genetic vulnerability.Reference Miles and McCarthy32,Reference Narita, Nagahori, Nishizawa, Yoshihara, Kawai and Ikeda63,Reference Miles, Takahashi, Haber and Hadden66,Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 Although specific genes are not clearly identified, studies considered family history and ancestry.Reference Miles, Takahashi, Haber and Hadden66,Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 Adopting an epigenetic viewpoint, considering parental monitoring and alcohol use can influence the development of AUD,Reference Sharmin, Kypri, Khanam, Wadolowski, Bruno and Mattick36,Reference Yuen, Chan, Bruno, Clare, Mattick and Aiken39,Reference Ryan, Jorm and Lubman46 it would be interesting to investigate the associations between genetics, family environment and AUD development across the severity and lifespan of ASD.

Findings suggest the risk of AUD increases with age in ASD and in the presence of co-occurring difficulties in clinical samples, an observation found in other literature within non-clinical samples.Reference Fortuna, Robinson, Smith, Meccarello, Bullen and Nobis18 However, the risk of AUD could be decreased with a prior diagnosis of ASD.Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 We hypothesise that a prior diagnosis of ASD explains some daily life experience and potential availability for support to manage symptoms. In the absence of appropriate support, ASD patients may seek other means to manage or alleviate symptoms. This may also offer an explanation as to why the risk of AUD was reduced for ASD populations receiving psychotropic medication.Reference Huang, Yang, Chien, Yeh, Chung and Tsai78

Alcohol use may lead to reduced sensory perception and inhibit cognitive processing, such as accessibility to self-critical memories, leading to greater symptom control.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69 Such motivations have been explored in non-clinical ASD samples yielding similar results.Reference Weir, Allison and Baron-Cohen16,Reference Levy and Witte48–Reference Pijnenburg, Kaplun, de Haan, Janecka, Smith and Reichenberg51 In comparison with general populations, motivations for alcohol use can fall into two categories: enhancement and coping.Reference Bresin and Mekawi86 Both of these predictors can lead to alcohol use problems. Yet, using alcohol to cope can lead directly to alcohol use problems, whereas enhancement is indirectly associated with use through alcohol use problems. This is comparable with the interrelated factors of self-medication (coping) and social facilitation (enhancement) found in this review for ASD-AUD.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69

The processes of how harmful alcohol use develops in ASD are unclear. Within wider literature, Cho et alReference Cho, Su, Kuo, Bucholz, Chan and Edenberg87 found longitudinal associations for two reinforcement cycles related to alcohol dependence, with a stronger association for negative reinforcement. In the context of ASD and this review, improved social interaction (positive) and relief from sensory processes (negative) could form reinforcing maintenance loops (see Box 1). Therefore, the function of alcohol use for ASD people could influence how AUD develops and provide a theoretical target for intervention. However, existing approaches would require appropriate adaptation to reduce barriers, create shared understanding and meet specific ASD population needs.Reference Brosnan and Adams47

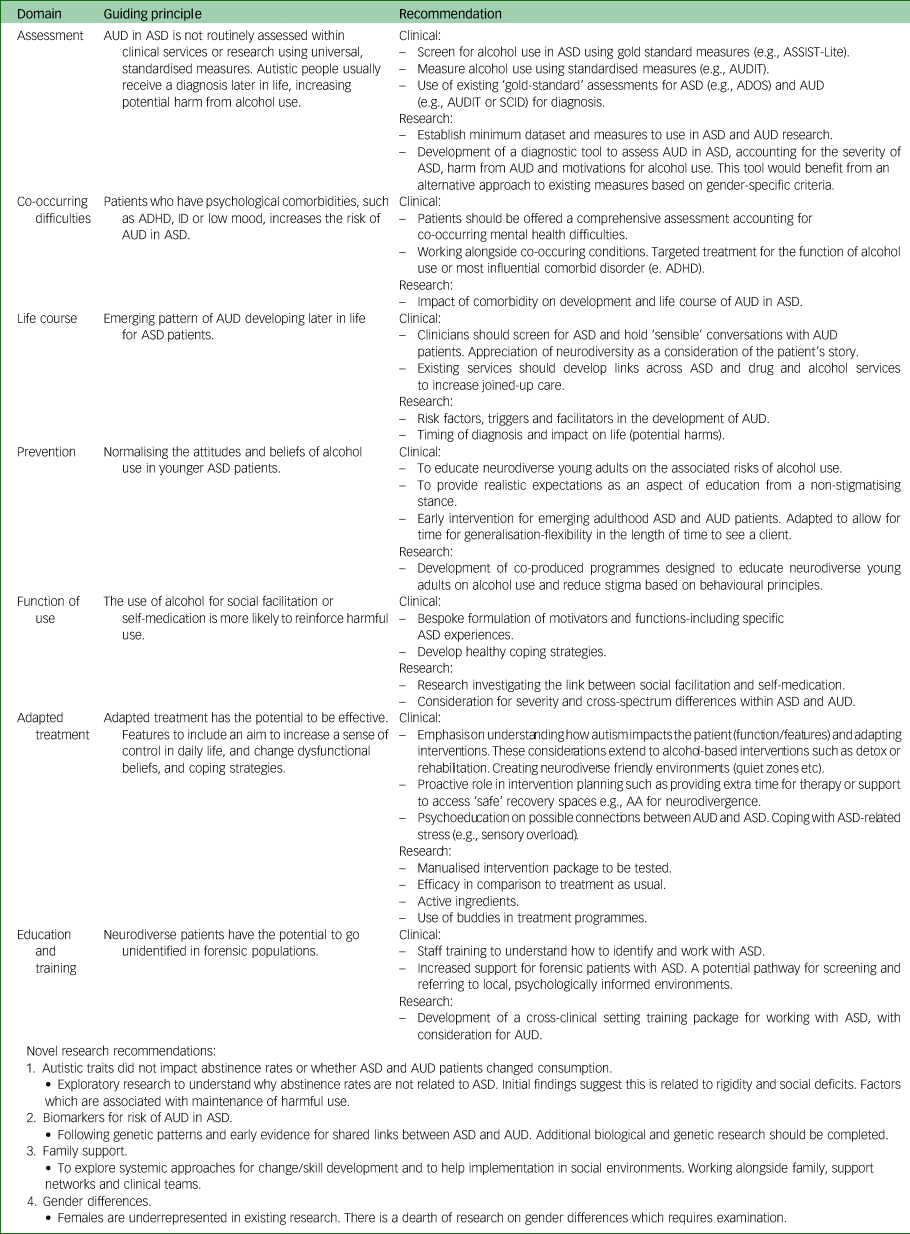

Principles of care and research

The findings of this review highlight the significant need for research to improve clinical practice for ASD-AUD patients. In Table 2, we have provided guiding principles for clinicians and researchers to consider and take forward, based on the review findings. Seven principles are outlined across assessment, consideration for co-occurring difficulties and life course, prevention, function of use, education and training and adapted treatment. We offer a further four novel research recommendations.

Table 2 Seven guiding principles related to aetiology and implications of alcohol use and autism. Included recommendations for clinical practice and novel research ideas.

AA, alcoholics anonymous; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule;Reference Cruz, Zubizarreta, Costa, Araújo, Martinho and Tubío-Fungueiriño83 ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ASSIST-Lite, Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test short-form (86); AUD, alcohol-use disorders; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (87); ID, Intellectual disability; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (88).

To outline some of our principles and recommendations, we draw on the findings of this review and the wider literature. As highlighted, autistic people may be accessing services undiagnosed,Reference Chaplin, McCarthy, Allely, Forrester, Underwood and Hayward71 and if a timely diagnosis could protect autistic people from developing AUD,Reference Yule, DiSalvo, Biederman, Wilens, Dallenbach and Taubin68,Reference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 routine assessment could prevent future harm. However, as the waiting time for ASD assessment grows,Reference Mendez, Oakley, Canitano, San José-Cáceres, Tinelli and Knapp8 current services could implement screening tools to inform clinical formulations. Hence, the development of a specific ASD-AUD screening tool may benefit future research. Subsequent studies should consider the overrepresentation of male participants, as indicated by this review, and the potential bias of some existing measures towards men.Reference Cruz, Zubizarreta, Costa, Araújo, Martinho and Tubío-Fungueiriño83 In addition, greater awareness is a promising sign of advocacy for the needs of autistic people, yet this does not necessarily translate to available services.Reference Zeidan, Fombonne, Scorah, Ibrahim, Durkin and Saxena7 Cross-service collaborations may prove fruitful for developing individual pathways to share resources. Similar to harm-reduction strategies, co-produced research, education and training could inform future prevention strategies.

A further interest is the emerging pattern that AUD develops later in life for autistic people.Reference Roy, Prox-Vagedes, Ohlmeier and Dillo67,Reference Yule, DiSalvo, Biederman, Wilens, Dallenbach and Taubin68 This poses the question of whether this could be attributed to the change in diagnostic criteria over timeReference Butwicka, Langstrom, Larsson, Lundstrom, Serlachius and Almqvist74 or to the limited resources to diagnose autistic adults.Reference Mendez, Oakley, Canitano, San José-Cáceres, Tinelli and Knapp8 We could also question whether it could be a result of the function or motivation to use alcohol as a coping strategy, as availability increases in adulthood.Reference Kronenberg, Slager-Visscher, Goossens, van den Brink and van Achterberg62,Reference Clarke, Tickle and Gillott69 Future longitudinal studies could explore the development of AUD and functions of use over time in autistic adults. This in turn could direct adapted treatment, such as one included study,Reference Walhout, van Zanten, DeFuentes-Merillas, Sonneborn and Bosma64 and future randomised controlled trials to test for efficacy.

Limitations

Due to the inconsistency of reporting demographics and severity of both spectrum disorders, comparisons between studies are difficult to establish. Without knowing the specificities across the spectrum of ASD with AUD present, it is likely to be difficult to meet the needs of this patient group adequately. The findings of this review should be taken with caution due to varied sample sizes, absence of control groups and lack of consideration for confounding variables. Furthermore, diagnoses sourced from medical records do not specify how assessments were conducted or which diagnostic tools were used. These issues are deepened by the differences in conceptualisation across classification manuals. In addition, this review focused on clinical samples only, excluding research on non-clinical samples, which could disregard existing applicable findings. Furthermore, the use of the MMAT to appraise the quality of studies may overlook methodological concerns that include more variables with non-standardised measures. None of the included studies were randomised controlled trials, and despite identifying possible associations, this review lacks the exploration of casual relationships.

This review, the first of its kind, highlights emerging trends and areas for future development in research and clinical practice. Included studies have identified some possible factors that may be associated with the development of AUD in ASD, yet further research is required. Future research would benefit from carefully defined variables, such as those identified by reviews like this, with the aim longitudinally to identify both causative factors and effective management strategies.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2024.824

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Gemma Scott for sharing her clinical experience, which informed recommendations for practice.

Author contributions

Concept and design of review: W.B., B.A., T.M., J.M., J.M.A.S.; data acquisition and quality appraisal: W.B., V.P., T.M.; Analysis: W.B., T.M., J.M., S.R.C., J.M.A.S.; drafting of manuscript: W.B., B.A., T.M., J.M., S.R.C., J.M.A.S.

Funding

This work was started as part of a priority-setting partnership funded by the Society for the Study of Addictions (see https://www.addiction-ssa.org/sabaa-substance-use-alcohol-and-behavioural-addictions-in-autism) and finalised without further funding.

Declaration of interest

W.B. declares that this review was completed in part fulfilment of Doctorate of Clinical Psychology thesis, King's College London.Reference Barber88 S.R.C. receives a stipend from Elsevier for Associate Editor work. J.M.: in the past 3 years, J.M. declares research grants for the following clinical trials: King's College London [KCL]); Indivior (trial of extended-release pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder; sponsor: KCL and South London & Maudsley National Health Service Trust); and Beckley PsyTech (phase 2a trial of 5-MeO-DMT for alcohol use disorder; sponsor: Beckley PsyTech). He is the senior academic advisor for the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, English Department of Health and Social Care, and a clinical academic consultant for the US National Institute on Drug Abuse, Clinic for Clinical Trials Network. He declares honoraria and travel support from PCM Scientific, OPEN Health and Indivior to contribute to scientific and educational meetings. He holds no stocks in any company. B.A., T.M., V.P., J.M.A.S. report no declarations of interest.

Transparency declaration

All authors declare the manuscript is honest, accurate and transparent of the review findings. The review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (No.: CRD42023430291). The protocol was edited to clinical samples only, as described in the main text.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.