Background

Epilepsy is a serious neurological disorder affecting approximately 50 million people worldwide.1,Reference de Boer, Mula and Sander2 In high-income countries, incidence rates range between 40 and 70/100 000 persons/year, with higher rates among children and elderly people.Reference MacDonald, Cockerell, Sander and Shorvon3 Incidence rates are much higher in resource-poor countries, being above 120/100 000/year, but even in high-income countries, poor people seem to have a higher incidence.Reference Ngugi, Bottomley, Kleinschmidt, Wagner, Kakooza-Mwesige and Ae-Ngibise4,Reference Ngugi, Kariuki, Bottomley, Kleinschmidt, Sander and Newton5 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), epilepsy accounts for about 0.5% of the global burden of all diseases with total annual costs, in Europe in 2004, of approximately 15.5 billion Euros.Reference Pugliatti, Beghi, Forsgren, Ekman and Sobocki6

People with epilepsy are among the most vulnerable in our society because epilepsy is a hidden disability and remains today a highly stigmatised condition because of ignorance and superstition caused by centuries of misconceptions towards this disorder.Reference Temkin7 Social stigma is a key aspect of chronic illnesses and negatively affects quality of life. It is characterised by different components, including enacted stigma (external behaviours and discrimination) and felt (perceived) stigma (shame and expectation of discrimination).Reference Scambler and Hopkins8,Reference Kaufman9 Stigma leads not only to discrimination and civil and human rights violations but also to poor access to healthcare and decreased adherence to treatment, ultimately increasing morbidity and mortality. Mental illness shares with epilepsy exactly the same issues because of centuries of misbeliefs, ignorance and superstition about mental health problems with similar consequences in terms of discrimination, violation of human rights and poor access to health resources.

Double stigma

What happens when two highly stigmatised conditions sensitive to cultural themes occur in the same individual? This phenomenon is known as double stigma and it is now getting attention for psychiatric disorders in other stigmatised medical conditions such as, for example, HIV, tuberculosis or obesity.Reference Daftary10 However, there is still very limited attention to the problem of double stigma in people with mental health issues and epilepsy. In this narrative review, we aimed at discussing the issue of double stigma in mental health with special reference to epilepsy.

Method

Articles were identified through searches in PubMed up to 31 October 2019 using the search terms ‘epilepsy’, ‘psychiatric disorders’, ‘stigma’. No language restrictions were applied. This search generated 111 abstracts. Articles were selected based on originality and relevance to the present topic. Additional articles were identified from the authors’ own files and from chosen bibliographies.

Results

How frequent are mental health problems in epilepsy?

Mental health problems are not uncommon in epilepsy. Data from cross-sectional epidemiological studies show that one in three people with epilepsy have a lifetime history of a psychiatric disorder and all major psychiatric disorders show prevalence rates in people with epilepsy higher than those reported in the general population.Reference Salpekar and Mula11 Furthermore, it is now established that there is a bidirectional relationship between epilepsy and psychiatric disorders.Reference Hesdorffer, Ishihara, Mynepalli, Webb, Weil and Hauser12

In adults, a meta-analysis of 14 population-based studies showed an overall prevalence of active depression in epilepsy of 23.1% (95% CI 20.6–28.3%) with an increased overall risk of 2.77 (95% CI 2.09–3.67) compared with the general population.Reference Fiest, Dykeman, Patten, Wiebe, Kaplan and Maxwell13 These estimates, however, vary considerably across studies depending on the ascertainment source (i.e. self-report versus screening tools versus structured clinical interviews), countries, regions and settings. A meta-analysis on anxiety disorders in over 3000 people with epilepsy showed a pooled prevalence of 20.2% (95% CI 15.3–26.0) with generalised anxiety disorder being most common (10.2%; 95% CI 7.7–13.5%).Reference Scott, Sharpe, Hunt and Gandy14 A meta-analysis of 58 studies of psychosis and related disorders showed a pooled prevalence of 5.6% (95% CI 4.8–6.4%) in unselected samples increasing to 7% (95% CI 4.9–9.1%) in people with temporal lobe epilepsy, with a pooled odds ratio for risk of psychosis compared with the general population of 7.8 (95% CI 2.8–21.8).Reference Clancy, Clarke, Connor, Cannon and Cotter15 Data from epilepsy surgery samples suggest an even higher prevalence.Reference Buranee, Teeradej, Chusak and Michael16 Still, studies in selected samples of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy have shown prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders up to 60%.Reference Hellwig, Mamalis, Feige, Schulze-Bonhage and van Elst17

Data from children and adolescents with epilepsy are not different despite an obvious emphasis on developmental disorders. A population-based study in 85 children and adolescents (aged 5–15) with active epilepsy in West Sussex in the UK reported a prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) of around 33%, autistic spectrum disorder of 21%, depression of 7% and anxiety of 13%.Reference Reilly, Atkinson, Das, Chin, Aylett and Burch18 A nationwide Norwegian registry study in an unselected paediatric population of over 1 000 000 children reported developmental and psychiatric comorbidities in 43% of children with epilepsy, with overall odds ratios (compared with the general population of children) of 10.7 (95% CI 9.5–12.1) for autism, 5.4 (95% CI 4.8–5.9) for ADHD, 2.3 (95% CI 1.8–3.0) for anxiety disorders and 1.8 (95% CI 1.4–2.5) for depression.Reference Aaberg, Bakken, Lossius, Lund Søraas, Håberg and Stoltenberg19 A study of 140 adolescents with epilepsy attending a Hong Kong hospital out-patient neurology clinic reported 22.1% rates for depression and 32.8% for anxiety.Reference Kwong, Lam, Tsui, Ngan, Tsang and Lai20

Stigma and double stigma in mental health

Stigma is a complex phenomenon and research in this area involves specialised disciplines including social sciences and social psychology. The French sociologist Emile Durkheim was probably the first to explore stigma as a social phenomenon but research on stigma in mental health probably started in the 1960s with the American sociologist Erwin Goffman,Reference Goffman21 followed by the publications of Thomas ScheffReference Scheff22 and Bruce LinkReference Link23. However, at that time, the debate focused on how psychiatry was organised, and how this was responsible for the stigma and public attitude towards people with mental health problems. Subsequent research on stigma in mental health progressed identifying different types of stigma and social group processes.Reference Link, Yang, Phelan and Collins24–Reference Corrigan, Kleinlein and Corrigan)26 The labelling, stereotyping, separation from others and consequent status loss are the key elements of stigma and they are ‘relevant only in a power situation that allows them to unfold’.Reference Link and Phelan27,Reference de Boer28 These studies have highlighted how powerful stereotypes are in our society and their deleterious impact primarily on patients themselves. In fact, negative stereotypes are so ingrained in the collective belief that they become an accepted part of people's belief including patients who internalise how society devalues them. This process is a key element of felt (perceived) stigma and it makes patients feel not empowered to change the situation and, ultimately, maintain the stigma itself.

Negative stereotypes about mental illness are well known. A survey investigating beliefs of random Web users around the world showed that only 7% of people believe that psychiatric disorders could be overcome and between 8% (high-income countries) and 16% (low-income countries) of people believe that individuals with mental health issues are more violent than others.Reference Seeman, Tang, Brown and Ing29 A cross-sectional survey in people with first-episode psychosis or depression investigated levels of discrimination through face-to-face interview.Reference Corker, Beldie, Brain, Jakovljevic, Jarema and Karamustafalioglu30 People with depression reported greater discrimination in regard to neighbours, dating, education, marriage, religious activities, physical health and acting as a parent than participants with first-episode psychosis. Data from a large prospective population study in Norway showed high chances of divorce in couples where one of the two is diagnosed with a mental illness.Reference Idstad, Torvik, Borren, Rognmo, Røysamb and Tambs31 A US study comparing fictitious job applications (n = 635) listing mental illness versus physical injury, showed significant discrimination for candidates with a history of mental illness, and this discrimination did not differ for jobs that could be done away from an office setting.Reference Hipes, Lucas, Phelan and White32

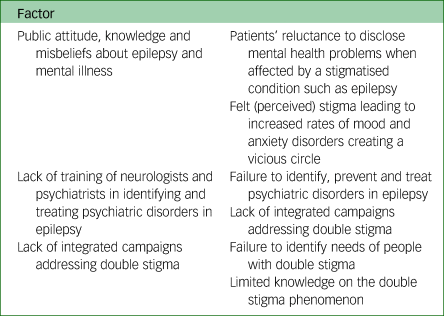

The main consequence of stigma is not simply a negative impact on quality of life for people with mental illness, as stigma has deleterious consequences from a clinical perspective serving as a barrier to health-seeking/diagnosis, treatment and adherence.Reference Sirey, Bruce, Alexopoulos, Perlick, Friedman and Meyers33 A systematic review investigating the relationship between mental health-related stigma and help-seeking clearly showed that stigmatising attitudes towards people with a mental illness is associated with less active help-seeking from patients and their relatives.Reference Schnyder, Panczak, Groth and Schultze-Lutter34 In this context, people with an already stigmatised condition often do not reveal their mental state to healthcare professionals for fear of being stigmatised further. Also, healthcare professionals dealing with people with epilepsy are often not skilled in detecting psychological symptoms and, even when they do, they often fail to take the necessary action for further assessment, management and referral.Reference Hesdorffer35,Reference Lopez, Schachter and Kanner36 For all these reason, people with double stigma have to fight further in order to receive the best possible care (Appendix).

The European Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 has specifically included, among the proposed actions, evidence-based anti-stigma activities in high-risk groups.37 In 2018, the WHO published the United Nations Common Position on Ending HIV, TB and Viral Hepatitis through Intersectoral Collaboration.38 Among the shared principles, it is specifically mentioned that ending these epidemics is not just the absence of the disease but also a state of complete, physical, mental and social well-being, acknowledging the issue of double stigma in these patients. It is quite astonishing that none of these documented listed epilepsy among those medical conditions already stigmatised.

The double stigma of epilepsy and mental health: a complex paradigm

The impact of stigma is immediately evident on the more intimate life domains of people such as cohabitation and marriage. Patients with epilepsy are less likely to be married or more likely to be divorced as compared with people with other chronic medical conditions.Reference Friedrich, Taslak, Tomasović and Bielen39–Reference Tedrus, Fonseca and Pereira41 A systematic review of the social outcomes of adults with a history of childhood-onset epilepsy showed that only one in three people were in a romantic relationship, one in three lived independently and one in five had children.Reference Puka, Tavares and Speechley42 In low-income countries, people with epilepsy are particularly vulnerable to discrimination as in many of these countries there are no anti-discrimination laws or policies in place. A study from Tanzania, showed that only one in three people with epilepsy was in education or in paid employment.Reference Goodall, Salem, Walker, Gray, Burton and Hunter43 However, stigma easily overcomes anti-discrimination laws and policies and problems are very similar in high-income countries where anti-discrimination laws may not be effective. A survey from Australia showed that 47% of patients with epilepsy were able to document unfair treatment in the workplace.Reference Bellon, Walker, Peterson and Cookson44 A systematic review of employability in people with epilepsy showed a mean adjusted employment rate of 58% with no significant differences between continents.Reference Wo, Lim, Choo and Tan45 Still, this study showed similar employment rates in people with uncontrolled and those with controlled seizures, suggesting that unemployment is likely to be related to non-clinical factors.Reference Wo, Lim, Choo and Tan45

The concept of double stigma in epilepsy and mental health is more complex than the simple additional effects of the two stigmatised conditions. In fact, felt (perceived) stigma is an important determinant per se of mental health problems in epilepsy, creating a vicious circle.Reference Yeni, Tulek, Simsek and Bebek46,Reference Yıldırım, Ertem, Ceyhan Dirican and Baybaş47 In epilepsy, perceived stigma is a risk factor for the development of mood and anxiety disorders,Reference Peterson, Walker and Shears48,Reference Lee, Jeon, No, Park, Kim and Kwon49 which, at the same time, are risk factors for perceived stigma, along with other personality features.Reference Shi, Wang, Ying, Zhang, Liu and Zhang50,Reference Lee, Lee, No, Lee, Ryu and Jo51 This phenomenon is present in low-income as well as high-income countries, independently of background, although specific cultures may have greater degrees of stigma. A study from Ethiopia showed that perceived stigma is associated with depression in people with epilepsy.Reference Chaka, Awoke, Yohannis, Ayano, Tareke and Abate52 In the same way, a study from Italy showed that feeling stigmatised correlates with depressive symptoms rather than seizure frequency.Reference Tombini, Assenza, Quintiliani, Ricci, Lanzone and De Mojà53 A systematic review of clinical correlates of stigma in adults with epilepsy showed that stigma is associated with depression and anxiety.Reference Baker, Eccles and Caswell54

Stigma affects not only patients but also their caregivers and has negative consequences on their mental health.Reference Seid, Demilew, Yimer and Mihretu55,Reference Rani and Thomas56 A cross-sectional study from the USA showed that caregivers of people with drug-resistant epilepsy experience high perceived stigma and burden levels.Reference Hansen, Szaflarski, Bebin and Szaflarski57 In low- and middle-income countries, 20% of mothers of children with epilepsy feel stigmatised because of their child's neurological condition.Reference Elafros, Sakubita-Simasiku, Atadzhanov, Haworth, Chomba and Birbeck58 The caregiver's perception of burden, together with the level of family functioning, are indirectly correlated with depressive symptoms in people with epilepsy via the mediating effect of caregiver depression.Reference Han, Kim and Lee59 The same phenomena are reported also in high-income countries. A UK study showed that mothers of young children with epilepsy report high levels of parenting stress as compared with mothers of children with non-epilepsy related neurodisabilities.Reference Reilly, Atkinson, Memon, Jones, Dabydeen and Das60

Studies addressing the phenomenon of double stigma in epilepsy are almost non-existent. A study from Brazil showed that cohabiting relatives of people with epilepsy and depression experience more stigma than those with epilepsy only.Reference Tedrus, Pereira and Zoppi61 A study from Bosnia Herzegovina, showed that patients with epilepsy and depression present with higher levels of stigma as compared with those with epilepsy only.Reference Suljic, Hrelja and Mehmedika62 However, the phenomenon of double stigma is not analysed in detail.

What can be done to address the problem? Anti-stigma campaigns and educational initiatives about epilepsy can have positive effects on well-being and mental health problems. An educational campaign in rural Bolivia aimed at improving knowledge towards epilepsy showed that the improved knowledge and attitude towards epilepsy was associated with reduced stigma, better quality of life and fewer depressive symptoms.Reference Giuliano, Cicero, Padilla, Rojo Mayaregua, Camargo Villarreal and Sofia63 However, as pointed out by a study from the Philippines, these strategies may not always be successful in the context of double stigma if context-specific approaches are not considered.Reference Tanaka, Tuliao, Tanaka, Yamashita and Matsuo64 It is not possible to develop effective campaigns and policies on double stigma in epilepsy and mental health without a clear analysis of the problem and for this reason, further studies on this phenomenon are urgently needed.

The new definition of epilepsy published in 2014 now defines epilepsy as a disorder of the brain characterised not just by recurrent seizures but also by its psychosocial consequencesReference `Fisher, Acevedo, Arzimanoglou, Bogacz, Cross and Elger65 and the new classification of syndromes published in 2017 recognises comorbidities as an important part of the diagnostic process.Reference Scheffer, Berkovic, Capovilla, Connolly, French and Guilhoto66 Furthermore, the new WHO global report on epilepsy also mentions the presence of psychiatric disorders in epilepsy and the importance of addressing them.1 These necessary preliminary steps are helpful as they lead to the global acknowledgement of mental health problems in people with epilepsy as well as the associated double stigma but significant work still needs to be done in terms of education (for example society, patients, and healthcare providers) and access to care.

Discussion

Lack of studies on the phenomenon of double stigma represents a major concern and more research in this area is needed. Both quantitative and qualitative studies as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses are required to better appreciate the key issues that exist for patients with both epilepsy and mental disorders. In fact, future anti-stigma campaigns will need to take into account the phenomenon of double stigma in order to develop targeted and focused interventions.

Stigma is unacceptable and everyone has the right to be protected from it. Counteracting stigma and discrimination is a duty of governments, health services, medical schools, medical societies, patients’ organisations, families and the general public. Advocacy can take many forms and it represents the best way to fight stigma and to empower people with epilepsy and mental health problems.Reference Sudlesky and Schachter67

Author contributions

M.M. conceptualised the paper and wrote the first draft. K.R.K. conceptualised the paper, reviewed for intellectual content, and added critical comments. All authors approved the original submission. All authors helped to revise and approved the final version.

Declaration of interest

K.R.K. is the Editor-in-Chief of BJPsych Open and a member of the BJPsych editorial board.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.58.

Appendix

Consequences of double stigma in people with epilepsy and mental illness

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.