The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound effects on population health, resulting from both actual COVID-19 infection and collateral effects of the pandemic.Reference Simon, Schenk, Palm, Faltraco and Thome1 A rise in mental illness was expected to follow the pandemic, caused by COVID-19-related factors such as fear, bereavement, social isolation and socioeconomic impact.Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely and Arseneault2 Also, many people were projected to experience increased levels of alcohol and drug use, insomnia and anxiety.3 Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to the largest global economic shock in decades.4 Therefore, the impact of economic recessions on mental health and well-beingReference Parmar, Stavropoulou and Ioannidis5 may further contribute to the negative effects of the pandemic. Indeed, negative mental health effects from previous epidemics and economic crises have also been reported.Reference Parmar, Stavropoulou and Ioannidis5–Reference Marazziti, Avella, Mucci, Della Vecchia, Ivaldi and Palermo7

Collecting high-quality data on the mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has therefore been identified as an immediate research priority, and international comparisons will be especially helpful in this regard.Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely and Arseneault2 The aim of this report is to systematically review the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on mental health, and provide information about possible effects that may add to this as a result of an eventual economic crisis following the pandemic. Therefore, we intend to map information on the impact of previous pandemics/epidemics similar to COVID-19, and the impact of earlier economic crises, to guide the prevention and management of negative mental health effects following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

The searches were designed in collaboration with a university librarian, and conducted on 6 January 2021 in PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO and Sociological Abstracts (see search strings in Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.587). The searches were restricted to the years 2000–2021 and the English language, and reference lists of systematic reviews were scanned.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

(a) population: general population and/or any specific populations;

(b) exposure: COVID-19 or pandemics and epidemics similar to COVID-19 (Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H1N1 influenza (swine flu)), or economic crises (see search strings in Supplementary Appendix 1 for details);

(c) comparator: pre-pandemic/epidemic or pre-crisis measures or unaffected geographical areas;

(d) outcome: mental health outcomes (see search strings in Supplementary Appendix 1 for details);

(e) type of study: longitudinal cohort and repeated cross-sectional studies.

Study selection and data extraction

The titles and abstracts were independently screened by two researchers, in pairs (M.A., E.P., W.O., O.S., P.F., M.E.N., R.C., L.M. and F.A.). Disagreement was resolved through discussion among the pair or by consulting a third researcher within the team. Articles included for full-text screening were assessed against the inclusion criteria by two researchers. This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow8 and the review protocol has been pre-registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; identifier CRD42021252774; available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=252774). The data were collected by one researcher (M.A., E.P., O.S., P.F., M.E.N., R.C., L.M., F.A. or C.D.). The extracted data were then checked by another researcher (M.A. or M.E.N.).

Risk-of-bias quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale,Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welch and Losos9 and the assessment ratings for each individual study can be found in the table in Supplementary Appendix 2. The assessment was done independently by two researchers (M.A. and M.E.N.); disagreement was resolved by discussion between them. The study quality was defined as high (7–9 points), fair (5–6 points) or low (≤4 points).

Qualitative synthesis and harvest plots

Because of the large variation in outcomes measures reported in the included studies (relative risk, mean score, P-values only, frequencies, no numerical data in the results reported, etc.), we chose to conduct a qualitative synthesis instead of a meta-analysis, as recommended in the literature.Reference McKenzie, Brennan, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page10,Reference Campbell, McKenzie, Sowden, Katikireddi, Brennan and Ellis11 Graphical display of the directions of association across multiple variables is recommended for qualitative synthesis,Reference McKenzie, Brennan, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page10 and we have therefore visualised the direction of associations between the exposures and outcomes of interest in harvest plots in Figs 2–4.Reference Ogilvie, Fayter, Petticrew, Sowden, Thomas and Whitehead12 Further, we performed a grouping by potential moderators: study setting (the country of study origin, further combined into geographical regions) and study size (subdivided into the smaller studies with <1000 participants, medium-sized studies with 1000–10 000 participants and larger studies with >10 000 participants). The grouping by study size mirrors an assessment of a ‘small-study effect’ (i.e. if significant associations are found mainly in small underpowered studies, compared with the results of larger studies),Reference Page, Higgins, Sterne, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page13 which is indicative of publication bias.

Results

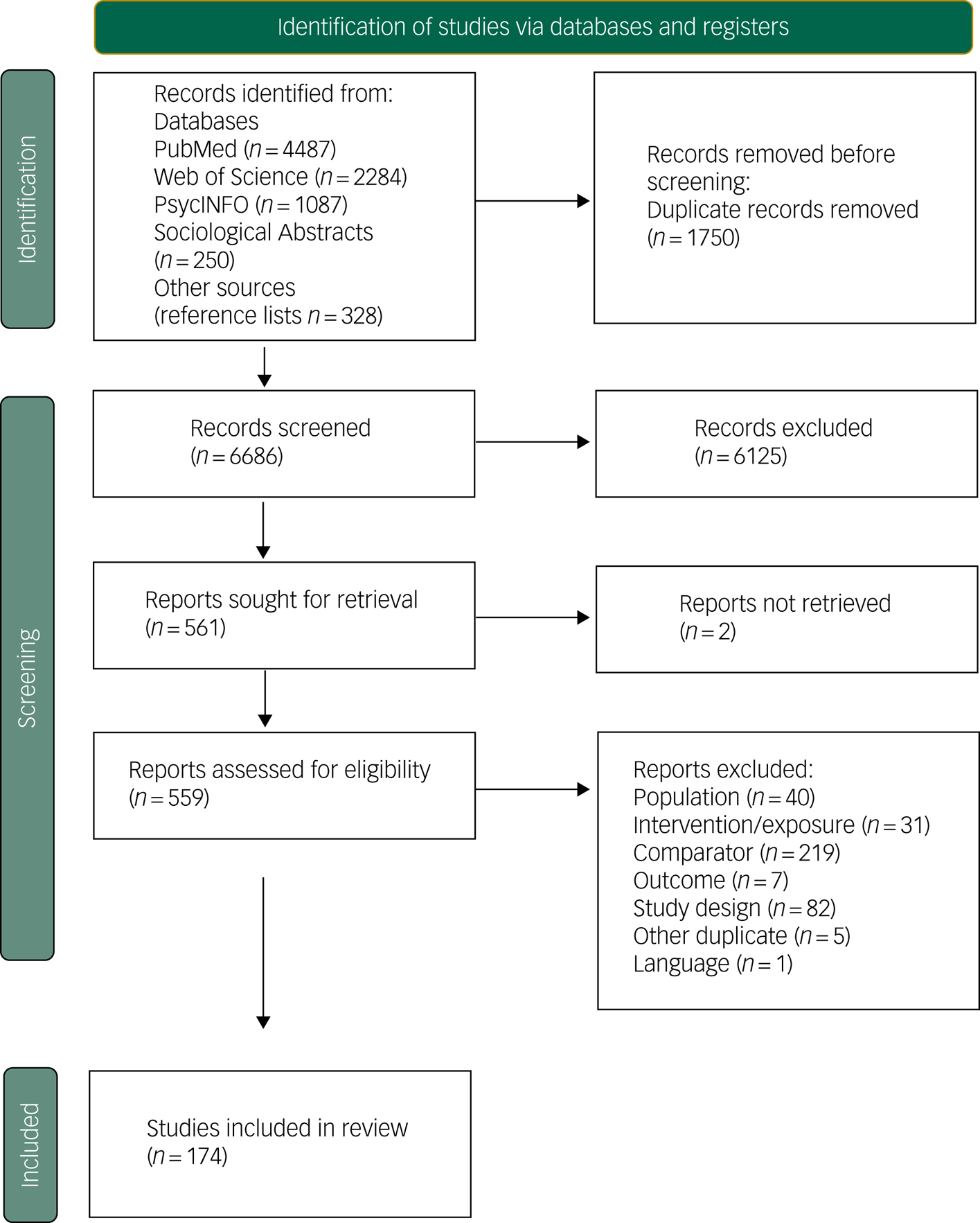

Figure 1 shows the results of the selection process. We screened 6686 studies by title and abstract. The full texts of 559 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 174 studies met our selection criteria and were included. Articles excluded at the full-text stage are listed in Supplementary Appendix 3, with reasons for exclusion.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, including searches of databases and registers.

Details about the included studies are given in Tables 1–3 in Supplementary Appendix 4. A qualitative summary of the findings is provided below, divided by type of exposure (COVID-19, economic crises or SARS) and outcome (affective disorders, suicides, other mental health problems and healthcare utilisation). For each exposure–outcome combination, the summary presents the direction of reported associations as well as study populations and settings.

COVID-19 exposure

Altogether, 87 studies were included assessing mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, where 43 focused on affective disorders, four assessed suicides, 30 assessed other mental health outcomes and ten examined mental healthcare utilisation.

Affective disorders

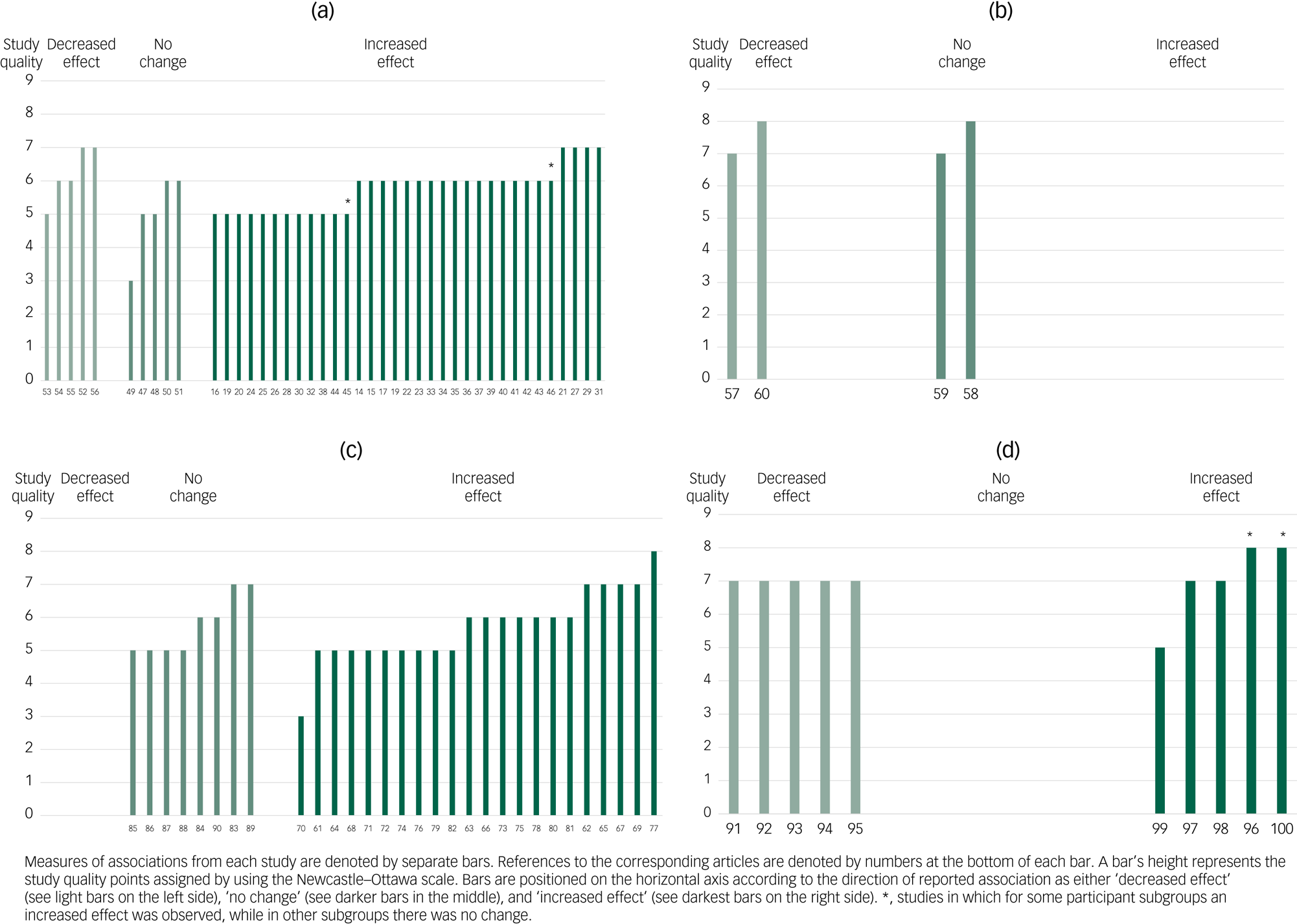

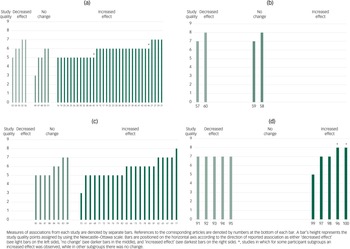

Among the studies on affective disorders (Fig. 2(a)), 31 found increases during the COVID-19 pandemicReference Meda, Pardini, Slongo, Bodini, Zordan and Rigobello14–Reference Elmer, Mepham and Stadtfeld44 and two found increases in subgroups of participants.Reference Janssen, Kullberg, Verkuil, van Zwieten, Wever and van Houtum45,Reference Gallagher, Bennett and Roper46 These were conducted on population-based samples (151–336 52 participants);Reference Ettman, Abdalla, Cohen, Sampson, Vivier and Galea17,Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson18,Reference Wanberg, Csillag, Douglass, Zhou and Pollard22,Reference Kwong, Pearson, Adams, Northstone, Tilling and Smith29,Reference Zhao, Wong, Luk, Wai, Lam and Wang33,Reference Creese, Khan, Henley, O'Dwyer, Corbett and Vasconcelos Da Silva39,Reference Twenge and Joiner40,Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle and Berger43 more specific healthy populations of various ages, life stages or occupations (93–7527 participants);Reference Meda, Pardini, Slongo, Bodini, Zordan and Rigobello14,Reference Krendl and Perry15,Reference Gallagher and Wetherell21,Reference Hamadani, Hasan, Baldi, Hossain, Shiraji and Bhuiyan23–Reference Saraswathi, Saikarthik, Senthil Kumar, Madhan Srinivasan, Ardhanaari and Gunapriya27,Reference Huckins, daSilva, Wang, Hedlund, Rogers and Nepal34,Reference Li, Cao, Leung and Mak36–Reference Creese, Khan, Henley, O'Dwyer, Corbett and Vasconcelos Da Silva39,Reference Zhang, Xiang and Alejok41,Reference Zhang, Zaman, Silenzio, Kautz and Hoque42 and patients/populations with various somatic or psychiatric diagnoses (46–1 854 742 participants).Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jörg and Luteijn16,Reference Puhl, Lessard, Larson, Eisenberg and Neumark-Stzainer19,Reference Villani, Vetrano, Damiano, Paola, Ulgiati and Martin20,Reference Stojanov, Malobabic, Milosevic, Stojanov, Vojinovic and Stanojevic28,Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Henry, Carrier, Patten and Harb30–Reference Titov, Staples, Kayrouz, Cross, Karin and Ryan32,Reference Lim, Woo, Lim, Ng, Chan and Gandhi35 The studies were conducted in Hong Kong,Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong26,Reference Zhao, Wong, Luk, Wai, Lam and Wang33 the USA,Reference Krendl and Perry15,Reference Ettman, Abdalla, Cohen, Sampson, Vivier and Galea17–Reference Puhl, Lessard, Larson, Eisenberg and Neumark-Stzainer19,Reference Wanberg, Csillag, Douglass, Zhou and Pollard22,Reference Lee, Cadigan and Rhew24,Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Henry, Carrier, Patten and Harb30,Reference Huckins, daSilva, Wang, Hedlund, Rogers and Nepal34,Reference Twenge and Joiner40,Reference Zhang, Zaman, Silenzio, Kautz and Hoque42 the UK,Reference Gallagher and Wetherell21,Reference Kwong, Pearson, Adams, Northstone, Tilling and Smith29,Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Henry, Carrier, Patten and Harb30,Reference Huckins, daSilva, Wang, Hedlund, Rogers and Nepal34,Reference Creese, Khan, Henley, O'Dwyer, Corbett and Vasconcelos Da Silva39 Germany,Reference Jacob, Smith, Koyanagi, Oh, Tanislav and Shin31,Reference Peters, Rospleszcz, Greiser, Dallavalle and Berger43 China,Reference Li, Cao, Leung and Mak36,Reference Chen, Chen, Pakpour, Griffiths and Lin37 Italy,Reference Meda, Pardini, Slongo, Bodini, Zordan and Rigobello14,Reference Villani, Vetrano, Damiano, Paola, Ulgiati and Martin20,Reference Zanardo, Manghina, Giliberti, Vettore, Severino and Straface25 Australia,Reference Titov, Staples, Kayrouz, Cross, Karin and Ryan32,Reference Magson, Freeman, Rapee, Richardson, Oar and Fardouly38 Bangladesh,Reference Hamadani, Hasan, Baldi, Hossain, Shiraji and Bhuiyan23 India,Reference Saraswathi, Saikarthik, Senthil Kumar, Madhan Srinivasan, Ardhanaari and Gunapriya27 Switzerland,Reference Elmer, Mepham and Stadtfeld44 South Sudan,Reference Zhang, Xiang and Alejok41 Canada,Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Henry, Carrier, Patten and Harb30 France,Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Henry, Carrier, Patten and Harb30 Singapore,Reference Lim, Woo, Lim, Ng, Chan and Gandhi35 SerbiaReference Stojanov, Malobabic, Milosevic, Stojanov, Vojinovic and Stanojevic28 and The Netherlands.Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jörg and Luteijn16 Among these studies, four were of high qualityReference Gallagher and Wetherell21,Reference Saraswathi, Saikarthik, Senthil Kumar, Madhan Srinivasan, Ardhanaari and Gunapriya27,Reference Kwong, Pearson, Adams, Northstone, Tilling and Smith29,Reference Jacob, Smith, Koyanagi, Oh, Tanislav and Shin31 and 27 were of fair quality.Reference Meda, Pardini, Slongo, Bodini, Zordan and Rigobello14–Reference Villani, Vetrano, Damiano, Paola, Ulgiati and Martin20,Reference Wanberg, Csillag, Douglass, Zhou and Pollard22–Reference Wong, Zhang, Sit, Yip, Chung and Wong26,Reference Stojanov, Malobabic, Milosevic, Stojanov, Vojinovic and Stanojevic28,Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Henry, Carrier, Patten and Harb30,Reference Titov, Staples, Kayrouz, Cross, Karin and Ryan32–Reference Elmer, Mepham and Stadtfeld44 A fair-quality study of adolescents and parents from The Netherlands found increased negative affect only in parents,Reference Janssen, Kullberg, Verkuil, van Zwieten, Wever and van Houtum45 and a fair-quality study of people with cancer from the UK found increased rates of depression only among those with certain cancer types.Reference Gallagher, Bennett and Roper46

Fig. 2 Harvest plot for the associations reported between exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic and (a) affective disorders, (b) suicides, (c) other mental health outcomes and (d) healthcare utilisation. Labels on the x-axis refer to the reference list entries for the studies.

Altogether, five studies with more defined samples of various ages, occupations and health conditions, with 25–3983 participants, found no change in affective disorders. They were conducted in CanadaReference McArthur, Saari, Heckman, Wellens, Weir and Hebert47 the USAReference Pinkham, Ackerman, Depp, Harvey and Moore48,Reference Sturman49 The NetherlandsReference van der Velden, Contino, Das, van Loon and Bosmans50 and Italy.Reference Baiano, Zappullo and Conson51 Four of these studies were of fair quality,Reference McArthur, Saari, Heckman, Wellens, Weir and Hebert47,Reference Pinkham, Ackerman, Depp, Harvey and Moore48,Reference van der Velden, Contino, Das, van Loon and Bosmans50,Reference Baiano, Zappullo and Conson51 and one was of low quality.Reference Sturman49

Some studies found unchanged or lower rates of affective disorders,Reference Pariente, Wissotzky Broder, Sheiner, Lanxner Battat, Mazor and Yaniv Salem52–Reference Li, Yu, Miller, Yang and Rouen55 and lower incidence of medication prescriptions.Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell and Carr56 These were conducted on populations of 164–241 458 participants, including postpartum women in Israel,Reference Pariente, Wissotzky Broder, Sheiner, Lanxner Battat, Mazor and Yaniv Salem52 patients in general practice in the UK,Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell and Carr56 medical students from the Republic of Kazakhstan,Reference Bolatov, Seisembekov, Askarova, Baikanova, Smailova and Fabbro54 patients from a sleep clinic from JapanReference Ubara, Sumi, Ito, Matsuda, Matsuo and Miyamoto53 and university students in China.Reference Li, Yu, Miller, Yang and Rouen55 Three of these studies were of fair qualityReference Ubara, Sumi, Ito, Matsuda, Matsuo and Miyamoto53–Reference Li, Yu, Miller, Yang and Rouen55 and two were of high quality.Reference Pariente, Wissotzky Broder, Sheiner, Lanxner Battat, Mazor and Yaniv Salem52,Reference Williams, Jenkins, Ashcroft, Brown, Campbell and Carr56

Suicides

Four studies assessed pandemic-period suicide rates in whole populations from Connecticut (USA),Reference Mitchell and Li57 Queensland (Australia),Reference Leske, Kõlves, Crompton, Arensman and de Leo58 JapanReference Isumi, Doi, Yamaoka, Takahashi and Fujiwara59 and Peru,Reference Calderon-Anyosa and Kaufman60 and found these had either decreasedReference Mitchell and Li57,Reference Calderon-Anyosa and Kaufman60 or remained unaltered (Fig. 2(b)).Reference Leske, Kõlves, Crompton, Arensman and de Leo58,Reference Isumi, Doi, Yamaoka, Takahashi and Fujiwara59 All four studies were of high quality.

Other mental health outcomes

There were 30 studies that assessed other mental health outcomes (Fig. 2(c)). Altogether, 12 studies were conducted on population-based samples and found decreases in mental health.Reference Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, Aschwanden, Strickhouser and Lee61–Reference Ran, Gao, Lin, Zhang, Chan and Deng72 These studies were conducted on populations ranging from 1003 to 17 452 individuals in the USA,Reference Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, Aschwanden, Strickhouser and Lee61,Reference Twenge and Joiner67,Reference McGinty, Presskreischer, Han and Barry68 the UK,Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf and John62–Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson65,Reference Niedzwiedz, Green, Benzeval, Campbell, Craig and Demou69 New Zealand,Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall and Lee66 Denmark,Reference Sonderskov, Dinesen, Santini and Ostergaard70 CanadaReference Bierman and Schieman71 and China.Reference Ran, Gao, Lin, Zhang, Chan and Deng72 Four of these studies were of high quality,Reference Pierce, Hope, Ford, Hatch, Hotopf and John62,Reference Daly, Sutin and Robinson65,Reference Twenge and Joiner67,Reference Niedzwiedz, Green, Benzeval, Campbell, Craig and Demou69 seven were of fair qualityReference Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti, Aschwanden, Strickhouser and Lee61,Reference Banks and Xu63,Reference Gray, O'Connor, Knowles, Pink, Simkiss and Williams64,Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall and Lee66,Reference McGinty, Presskreischer, Han and Barry68,Reference Bierman and Schieman71,Reference Ran, Gao, Lin, Zhang, Chan and Deng72 and one was of low quality.Reference Sonderskov, Dinesen, Santini and Ostergaard70

Ten other studies in more defined samples ranging from 21 to 3505 individuals also found deteriorations in mental health.Reference Shen and Bartram73–Reference Gomez, Anderson, Yu, Gutsche, Jablonski and Martin82 These included populations of different ages and occupations,Reference Shen and Bartram73–Reference Savage, James, Magistro, Donaldson, Healy and Nevill76,Reference Copeland, McGinnis, Bai, Adams, Nardone and Devadanam78,Reference Dragun, Veček, Marendić, Pribisalić, Đivić and Cena79,Reference Gomez, Anderson, Yu, Gutsche, Jablonski and Martin82 and patients with various somatic or psychiatric diagnoses,Reference Ohliger, Umpierrez, Buehler, Ohliger, Magister and Vallier77,Reference Castellini, Cassioli, Rossi, Innocenti, Gironi and Sanfilippo80–Reference Gomez, Anderson, Yu, Gutsche, Jablonski and Martin82 and were conducted in the USA,Reference Ohliger, Umpierrez, Buehler, Ohliger, Magister and Vallier77,Reference Copeland, McGinnis, Bai, Adams, Nardone and Devadanam78,Reference Gomez, Anderson, Yu, Gutsche, Jablonski and Martin82 Spain,Reference Reverté-Villarroya, Ortega, Lavedán, Masot, Burjalés-Martí and Ballester-Ferrando74 Switzerland,Reference Macdonald and Hülür75 Croatia,Reference Dragun, Veček, Marendić, Pribisalić, Đivić and Cena79 the UKReference Shen and Bartram73,Reference Savage, James, Magistro, Donaldson, Healy and Nevill76 and Italy.Reference Castellini, Cassioli, Rossi, Innocenti, Gironi and Sanfilippo80,Reference Giordano, Siciliano, De Micco, Sant'Elia, Russo and Tedeschi81 One was of high qualityReference Ohliger, Umpierrez, Buehler, Ohliger, Magister and Vallier77 and nine were of fair quality.Reference Shen and Bartram73–Reference Savage, James, Magistro, Donaldson, Healy and Nevill76,Reference Copeland, McGinnis, Bai, Adams, Nardone and Devadanam78–Reference Gomez, Anderson, Yu, Gutsche, Jablonski and Martin82

Eight of the studies did not find changes in mental health among study populations of 46–1870 participants. These populations were of various ages and occupations, both healthy and with somatic or mental health diagnoses, conducted in the USA,Reference Breslau, Finucane, Locker, Baird, Roth and Collins83–Reference Benham86 Sweden,Reference Kivi, Hansson and Bjälkebring87 GermanyReference Schäfer, Sopp, Schanz, Staginnus, Göritz and Michael88 and The Netherlands.Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries89,Reference van Gorp, Maurice-Stam, Teunissen, van de Peppel-van der Meer, Huussen and Schouten-van Meeteren90 Of these studies, two were of high qualityReference Breslau, Finucane, Locker, Baird, Roth and Collins83,Reference van Tilburg, Steinmetz, Stolte, van der Roest and de Vries89 and six were of fair quality.Reference Penner, Ortiz and Sharp84–Reference Schäfer, Sopp, Schanz, Staginnus, Göritz and Michael88,Reference van Gorp, Maurice-Stam, Teunissen, van de Peppel-van der Meer, Huussen and Schouten-van Meeteren90

Healthcare utilisation

Figure 2(d) presents a harvest plot for associations between COVID-19 and healthcare utilisation. Altogether, five studies that assessed admissions for mental health problems found decreases: emergency department presentations decreased at three health services in AustraliaReference Dragovic, Pascu, Hall, Ingram and Waters91 and two hospitals in Italy;Reference Stein, Giordano, Del Giudice, Basi, Gambini and D'Agostino92,Reference Capuzzi, Di Brita, Caldiroli, Colmegna, Nava and Buoli93 psychiatric emergency services presentations decreased in Paris, France;Reference Pignon, Gourevitch, Tebeka, Dubertret, Cardot and Dauriac-Le Masson94 and presentations to a paediatric emergency department decreased in the USA.Reference Leff, Setzer, Cicero and Auerbach95 All of these five studies were of high quality.

On the other hand, although acute care presentations for mental health diagnoses in the UK decreased, the patients admitted had more severe conditions.Reference Abbas, Kronenberg, McBride, Chari, Alam and Mukaetova-Ladinska96 Admissions for mental health problems increased at an acute medical unit,Reference Grimshaw and Chaudhuri97 and there was acceleration in urgent referrals to secondary mental health services in the UK.Reference Chen, She, Qin, Kershenbaum, Fernandez-Egea and Nelder98 In Italy, psychological morbidity worsened among 145 palliative care professionals.Reference Varani, Ostan, Franchini, Ercolani, Pannuti and Biasco99 An emergency department in New Zealand experienced overall decreases in mental health presentations, but relative increases in overdoses and self-harm.Reference Joyce, Richardson, McCombie, Hamilton and Ardagh100 FourReference Abbas, Kronenberg, McBride, Chari, Alam and Mukaetova-Ladinska96–Reference Chen, She, Qin, Kershenbaum, Fernandez-Egea and Nelder98,Reference Joyce, Richardson, McCombie, Hamilton and Ardagh100 of these studies were of high quality and one was of fair quality.Reference Varani, Ostan, Franchini, Ercolani, Pannuti and Biasco99

Economic crisis exposure

Altogether 84 studies were included assessing mental health impacts of the 2008 economic crisis. Among these, 15 studies focused on affective disorders, seven assessed mental healthcare utilisation, 37 assessed suicides and 25 assessed other mental health outcomes.

Affective disorders

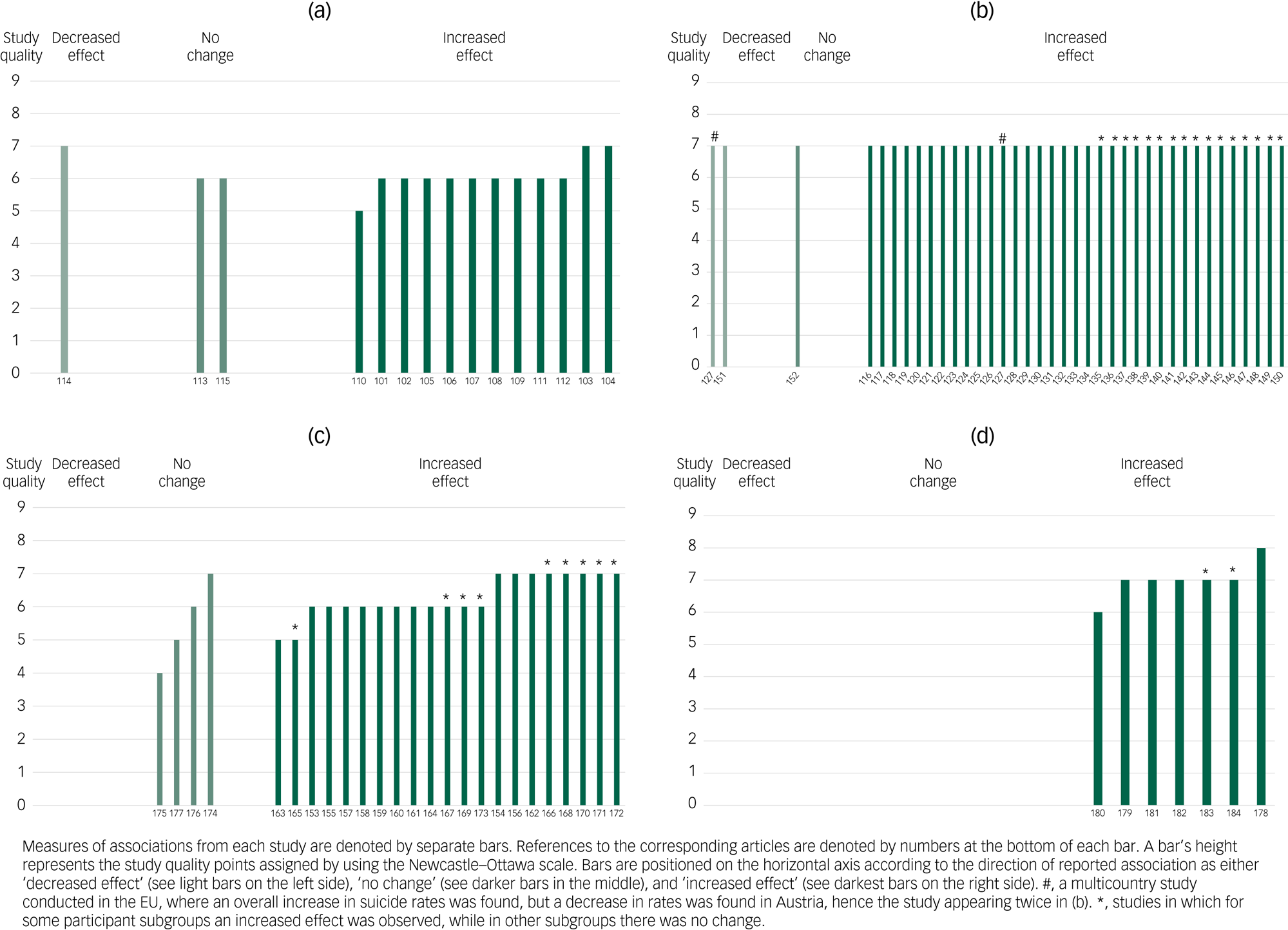

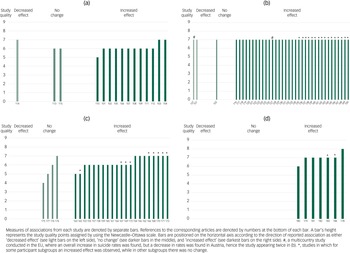

Figure 3(a) presents a harvest plot for associations between economic crises and affective disorders. All 15 studies reporting affective disorders as an outcome were population-based surveys. The findings from 12 of these studies, with populations ranging from 2011 to 81 313 participants, were that there was a significant increase in affective disorders.Reference Wang, Smailes, Sareen, Fick, Schmitz and Patten101–Reference Shi, Taylor, Goldney, Winefield, Gill and Tuckerman112 These studies were conducted in Canada,Reference Wang, Smailes, Sareen, Fick, Schmitz and Patten101 Hong Kong,Reference Lee, Guo, Tsang, Mak, Wu and Ng102 the USA,Reference Riumallo-Herl, Basu, Stuckler, Courtin and Avendano103–Reference Cagney, Browning, Iveniuk and English105,Reference Mehta, Kramer, Durazo-Arvizu, Cao, Tong and Rao108–Reference Dagher, Chen and Thomas111 Europe,Reference Riumallo-Herl, Basu, Stuckler, Courtin and Avendano103 SpainReference Chaves, Castellanos, Abrams and Vazquez106 and Australia.Reference Sargent-Cox, Butterworth and Anstey107,Reference Shi, Taylor, Goldney, Winefield, Gill and Tuckerman112 Two of these studies were of high qualityReference Riumallo-Herl, Basu, Stuckler, Courtin and Avendano103,Reference Tapia Granados, Christine, Ionides, Carnethon, Diez Roux and Kiefe104 and ten were of fair quality.Reference Wang, Smailes, Sareen, Fick, Schmitz and Patten101, Reference Lee, Guo, Tsang, Mak, Wu and Ng102, Reference Cagney, Browning, Iveniuk and English105–Reference Shi, Taylor, Goldney, Winefield, Gill and Tuckerman112

Fig. 3 Harvest plot for the associations reported between exposure to the economic crisis and (a) affective disorders, (b) suicides, (c) other mental health outcomes and (d) healthcare utilisation. Labels on the x-axis refer to the reference list entries for the studies.

A study on 815 adults aged over 50 years found no increase in depression among those most affected by the stock market crash, despite an increase in antidepressant medication use.Reference McInerney, Mellor and Nicholas113 Also, a study on 25- to 75-year-olds in the USA found that mental health improved.Reference Forbes and Krueger114 Among 106 158 participants aged over 15 years from 21 European countries, no effect of the crisis was found on depressive feelings.Reference Reibling, Beckfield, Huijts, Schmidt-Catran, Thomson and Wendt115 One study was of high quality,Reference Forbes and Krueger114 and two were of fair quality.Reference McInerney, Mellor and Nicholas113,Reference Reibling, Beckfield, Huijts, Schmidt-Catran, Thomson and Wendt115

Suicides

Altogether, 37 studies assessed suicide in relation to the 2008 economic crisis, and all of these studies were of high quality (Fig. 3(b)). Altogether, 19 studies found increased suicide rates at the level of the total population after the start of the crisis. These were conducted on the populations of Italy (Milan)Reference Merzagora, Mugellini, Amadasi and Travaini116 (suicides as a result of mental and behavioural disorders, ItalyReference De Vogli, Vieno and Lenzi117), Greece,Reference Zilidis, Papagiannis and Rachiotis118–Reference Kontaxakis, Papaslanis, Havaki-Kontaxaki, Tsouvelas, Giotakos and Papadimitriou123 SpainReference Lopez Bernal, Gasparrini, Artundo and McKee124 (suicide attempts in SpainReference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson125), the European Union,Reference Reeves, McKee and Stuckler126–Reference Laanani, Ghosn, Jougla and Rey128 Canada,Reference Reeves, McKee and Stuckler126 England,Reference Laanani, Ghosn, Jougla and Rey128–Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson, Scott-Samuel, McKee and Stuckler130 the USAReference Agrrawal, Waggle and Sandweiss131–Reference Carriere, Marshall and Binkley133 and South Korea.Reference Chan, Caine, You, Fu, Chang and Yip134

Some studies reported increases in suicide rates in specific population subgroups,Reference Rachiotis, Stuckler, McKee and Hadjichristodoulou135,Reference Alexopoulos, Kavalidou and Messolora136 among menReference Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth, Hawton, Kapur and Fearn137–Reference Corcoran, Griffin, Arensman, Fitzgerald and Perry139 or attributable to specific factors such as unemployment.Reference Mattei and Pistoresi140–Reference Cylus, Glymour and Avendano145 These studies were conducted in Greece,Reference Rachiotis, Stuckler, McKee and Hadjichristodoulou135,Reference Alexopoulos, Kavalidou and Messolora136 Italy,Reference Mattei and Pistoresi140 Australia,Reference Milner, Morrell and LaMontagne141 Spain,Reference Ruiz-Perez, Rodriguez-Barranco, Rojas-Garcia and Mendoza-Garcia138,Reference Iglesias-García, Sáiz, Burón, Sánchez-Lasheras, Jiménez-Treviño and Fernández-Artamendi142,Reference Rivera, Casal and Currais143 Barcelona (Spain),Reference López-Contreras, Rodríguez-Sanz, Novoa, Borrell, Medallo Muñiz and Gotsens144 the UK,Reference Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth, Hawton, Kapur and Fearn137 IrelandReference Corcoran, Griffin, Arensman, Fitzgerald and Perry139 and the USA.Reference Alexopoulos, Kavalidou and Messolora136,Reference Cylus, Glymour and Avendano145 A study from 29 countries in the European Union found a general relationship between the economic environment and suicide rates.Reference Fountoulakis, Kawohl, Theodorakis, Kerkhof, Navickas and Höschl146

A study conducted on the male population of 20 countries in the European Union found job losses to be a determinant of suicide risk, and greater spending on active labour market policies and social capital mitigated risks.Reference Reeves, McKee, Gunnell, Chang, Basu and Barr147 A study from 27 European countries, 18 North and South American countries, eight Asian countries, and one African country found that suicide rates increased in the European and North and South American countries, particularly in men and in countries with higher levels of job loss.Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell148 In Italy, periods of economic fluctuations were associated with male suicides, whereas severe economic downturns were associated with increased rates overall,Reference Mattei, Pistoresi and De Vogli149 and gross domestic product was associated with suicides because of financial problems.Reference Mattei, Ferrari, Pingani and Rigatelli150

Finally, one study in Piraeus, Greece, found a slight decrease in suicide rates,Reference Paraschakis, Michopoulos, Efstathiou, Christodoulou, Boyokas and Douzenis151 and a study including all European Union countries found decreased rates in Austria.Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee127 Also, a study in Crete, Greece, found no overall increase in suicide rates.Reference Basta, Vgontzas, Kastanaki, Michalodimitrakis, Kanaki and Koutra152

Other mental health outcomes

Most of the 25 studies assessing other mental health outcomes (Fig. 3(c)) were conducted on nationally or regionally representative samples, and the clear majority found evidence for increased mental distress.Reference Blomqvist, Burström and Backhans153–Reference Gudmundsdottir162 The studies that presented results at the population level included 3479–306 664 participants from Sweden,Reference Blomqvist, Burström and Backhans153 the UK,Reference Thomson, Niedzwiedz and Katikireddi155 Italy,Reference Odone, Landriscina, Amerio and Costa156 Spain,Reference Urbanos-Garrido and Lopez-Valcarcel157 England,Reference Thomson and Katikireddi154,Reference Katikireddi, Niedzwiedz and Popham159 Australia,Reference Parker, Jerrim and Anders160 Iceland,Reference Gudmundsdottir162 the Valencian Community in SpainReference Tamayo-Fonseca, Nolasco, Moncho, Barona, Irles and Más158 and 36 mainly European countries.Reference Gonza and Burger161 Three of these studies were of high qualityReference Thomson and Katikireddi154,Reference Odone, Landriscina, Amerio and Costa156,Reference Gudmundsdottir162 and seven were of low quality.Reference Blomqvist, Burström and Backhans153,Reference Thomson, Niedzwiedz and Katikireddi155,Reference Urbanos-Garrido and Lopez-Valcarcel157–Reference Gonza and Burger161 Also, two studies on more defined populations of 2050 medical researchers in Greece,Reference Sifaki-Pistolla, Chatzea, Melidoniotis and Mechili163 and 13 000 children aged 4–17 years in the USA,Reference Golberstein, Gonzales and Meara164 found decreases in mental health. Both studies were of fair quality.

Some of the population-based studies, ranging from 3755 to 11 743 participants, showed decreases in mental health only among particular population groups,Reference Houdmont, Kerr and Addley165–Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Bermúdez-Tamayo and Rodríguez-Barranco171 or under higher rates of precarious employment and lower health spending. These studies were conducted in Spain,Reference Bartoll, Palència, Malmusi, Suhrcke and Borrell167,Reference Rajmil, Medina-Bustos, Fernandez de Sanmamed and Mompart-Penina169,Reference Ruiz-Pérez, Bermúdez-Tamayo and Rodríguez-Barranco171 Ireland,Reference Houdmont, Kerr and Addley165 Iceland,Reference Hauksdóttir, McClure, Jonsson, Olafsson and Valdimarsdóttir166 FranceReference Malard, Chastang and Niedhammer168 and the UK.Reference Lindström and Giordano170 In the USA, retail sales for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors were not associated with unemployment, but there were positive associations for opioids and phosphodiesterase inhibitors.Reference Kozman, Graziul, Gibbons and Alexander172 Five of these studies were of high qualityReference Hauksdóttir, McClure, Jonsson, Olafsson and Valdimarsdóttir166,Reference Malard, Chastang and Niedhammer168,Reference Lindström and Giordano170–Reference Kozman, Graziul, Gibbons and Alexander172 and three were or fair quality.Reference Houdmont, Kerr and Addley165,Reference Bartoll, Palència, Malmusi, Suhrcke and Borrell167,Reference Rajmil, Medina-Bustos, Fernandez de Sanmamed and Mompart-Penina169

Also, one study with a cohort of 3321 mothers and 4089 children in Australia found that girls experienced an increase in mental health problems, but not boys or mothers.Reference Bubonya, Cobb-Clark, Christensen, Johnson and Zubrick173 This study was of fair quality.

Four studies found no changes in mental health outcomes. They were conducted on a population-based sample in the UK;Reference Boyce, Delaney and Wood174 a nationally representative sample of adults aged over 50 years in Ireland;Reference Barrett and O'Sullivan175 a study of 21 European countries;Reference Sarracino and Piekalkiewicz176 and a study of children aged 11–15 years from Israel, the USA and 31 countries in Europe.Reference Rathmann, Pförtner, Hurrelmann, Osorio, Bosakova and Elgar177 One of these studies was of high quality,Reference Boyce, Delaney and Wood174 two were of fair qualityReference Sarracino and Piekalkiewicz176,Reference Rathmann, Pförtner, Hurrelmann, Osorio, Bosakova and Elgar177 and one was of low quality.Reference Barrett and O'Sullivan175

Healthcare utilisation

Figure 3(d) presents a harvest plot for economic crises and healthcare utilisation. Five of the seven studies assessing changes in healthcare utilisation for mental health problems found increases in rates. They addressed in-patient admissions for affective disorders in Italy,Reference Wang and Fattore178 hospital admissions owing to depression in Taiwan,Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin179 primary care patients in Spain,Reference Gili, Roca, Basu, McKee and Stuckler180 general practice patients in the UKReference Kendrick, Stuart, Newell, Geraghty and Moore181 and hospital morbidity data in Spain.Reference Medel-Herrero and Gomez-Beneyto182 Four studies were of high qualityReference Wang and Fattore178,Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin179,Reference Kendrick, Stuart, Newell, Geraghty and Moore181,Reference Medel-Herrero and Gomez-Beneyto182 and one was of fair quality.Reference Gili, Roca, Basu, McKee and Stuckler180

Two studies did not find overall increases in mental healthcare utilisation: in the UK, rates of self-harm among patients increased in Derby and among males in Manchester, but not in in Oxford;Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness and Cooper183 in the USA, physician visits owing to mental health disorders decreased after the onset of the crisis, but the use of psychotropic medications increased.Reference Chen and Dagher184 Both of these studies were of high quality.

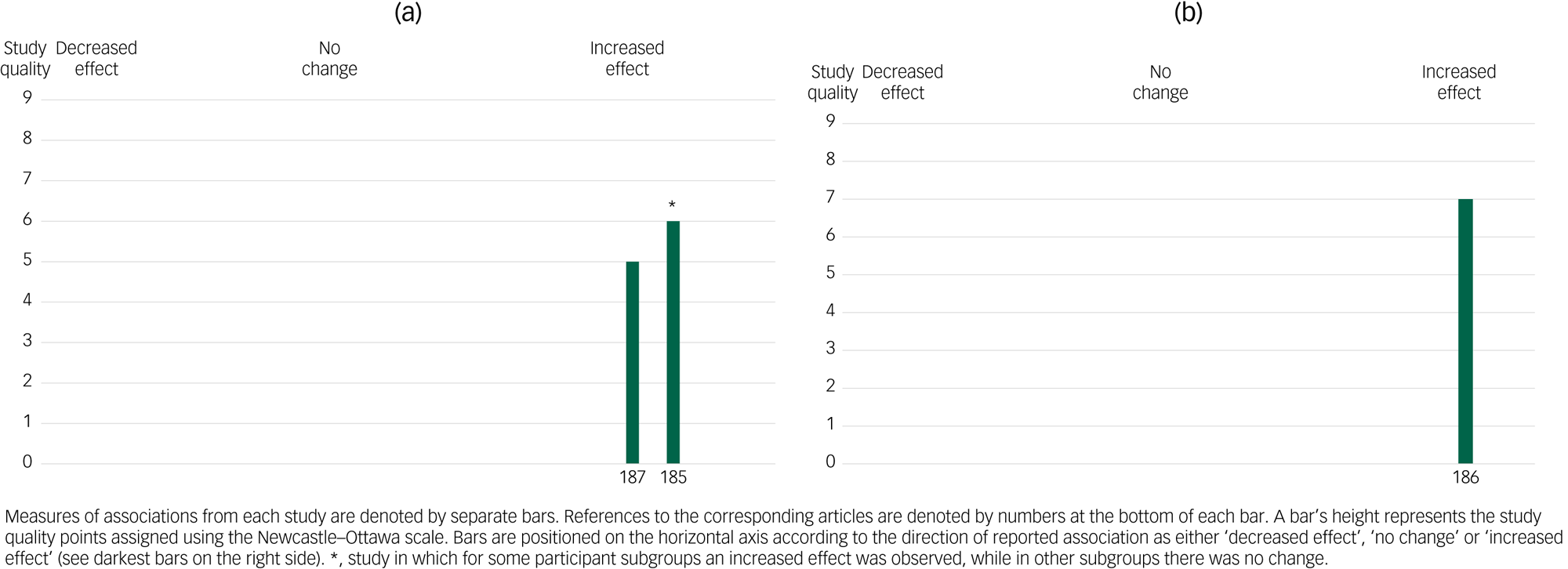

SARS exposure

Our review also yielded three studies addressing changes in mental health before and after the onset of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong (Fig. 4(a) and (b)). All of these studies were conducted on adults of older age.Reference Lai185–Reference Yu, Ho, So and Lo187 One study based on a stratified random sample showed no changes in depression among men, but an increase in depression among women. Another study found an excess in suicide rates among older adults.Reference Cheung, Chau and Yip186 Finally, a study of a random sample of women showed increases in depression and perceived stress.Reference Yu, Ho, So and Lo187 All of these studies were of fair quality.

Fig. 4 Harvest plot for the associations reported between exposure to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic and (a) other mental health outcomes and (b) suicides.Labels on the x-axis refer to the reference list entries for the studies.

Potential moderators

Table 1 in Supplementary Appendix 5 presents all reported exposures and outcomes, subdivided by potential moderators (geographical region and study size) separately, for each direction of change. The majority of both small and large studies, and studies from all geographical regions, reported increased negative effects on mental health, and thus neither the influence of geographical region differences nor the ‘small-study effect’ were considered to pose any risks for the interpretation of our results.

Discussion

This systematic review resulted in 174 studies assessing the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (87 studies), 2008 economic crisis (84 studies) and SARS epidemic (three studies). Most studies reported effects on affective disorders. Mostly, these studies found increased rates, as might be expected because of increased prevalence of risk factors. For the COVID-19 pandemic, these include uncertainty; loss of income; inactivity; limited access to basic services; increased access to food, alcohol and online gambling; and decreased social support.Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley and Jones188 However, some populations experienced improvements in affective disorders. These populations included postpartum women, university students, patients from general practice and patients from a sleep clinic. Future studies may delineate the ways in which these populations differed in terms of risk and protective factors, perhaps in part because of the various pandemic responses.

Our findings showed that mental healthcare utilisation as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic did not increase in the same manner as it did in result of the economic crisis; regulations on travel and quarantine may have resulted in mental healthcare visits becoming more difficult and impractical.Reference Yao, Chen and Xu189 Further, we found two studies that showed an increase in severity of mental health problems among those using services during the pandemic, indicating a shift away from seeking mental healthcare for milder problems, with a parallel increase in severity. Retaining existing mental health services, scaling up effective practices and promoting new practices that expand access and provide cost-effective delivery, as well as utilising to peer support and remote health delivery, should be prioritised during the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Moreno, Wykes, Galderisi, Nordentoft, Crossley and Jones188 Indeed, previous reports of the mental health effects of the SARS epidemic have illustrated that the negative consequences can even be maintained in the long term,Reference Parmar, Stavropoulou and Ioannidis5 thus further emphasising the importance of accessible prevention and treatment strategies.

Overall, we found that socioeconomic factors and unemployment resulting from the economic crisis had negative effects. Previous studies have also reported on the deleterious consequences of economic crises on mental health;Reference Parmar, Stavropoulou and Ioannidis5 that the main risk factors mediating these effects include unemployment, indebtedness, precarious working conditions, inequalities, lack of social connectedness and housing instability;Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec and Gonzalez-Fraile190 and that the negative impact of economic hardship on mental health may also continue further in bi-directional manner.Reference Ten Have, Tuithof, Van Dorsselaer, De Beurs, Jeronimus and De Jonge191 Also, in line with our findings, previous work has suggested that men at working age are at particular risk.Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec and Gonzalez-Fraile190 It may thus be expected that these population groups will also be negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn.

Contrary to the large number of studies assessing suicide rates in relation to the economic crisis, our review did not find many studies in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. The few studies we did identify showed either that rates decreased or remained unaltered, in contradiction to studies on the economic crisis. Follow-ups of included studies on the pandemic are short, but in the longer term, an increase in suicide rates as a result of the pandemic might be expected because of the increase in many of the known risk factors for suicide, including social isolation, substance misuse, economic hardship, unemployment and uncertainty.Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman and Huang192

A limitation of our study was the necessity to narrow the scope of our search strategies to search terms found in titles and abstracts, which was done because of the large number of published studies on the topic. This may have resulted in us missing some relevant studies. Also, we were not able to conduct searches in non-English-language publications or grey literature, which is also a limitation. However, a ‘small-study effect’ is unlikely to be present in our review, as shown in the analysis of study size as a potential moderator. Altogether, this indicates that the risk of publication bias, even if present, could be considered as low. Furthermore, our findings reflect what others have noted: toward the end of 2020, mental health was one of the most common topics for research being conducted on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, although the quantity was not matched by qualityReference Else193 – our included studies on the economic crisis were overall of better quality than those on the COVID-19 pandemic. Strengths of our study was its systematic nature and broad scope, which allowed us both to see emerging early evidence and possible longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health.

Our findings highlight the importance of making mental health services available, accessible and sustainable for those in need. Also, seeing as the socioeconomically disadvantaged are at increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes, these populations should be particular targets of policy interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, our review covers a broad range of mental health outcomes, both in clinical and general populations, in association with worldwide crises, which provides an invaluable basis for future systematic reviews that are more specific in their topics. Since most studies identified though our review were conducted in high-income countries, it would be invaluable to conduct more studies in low- and middle-income countries. Finally, we expect future research, with longer-term follow-up periods, to be able to elucidate the specific effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. In addition, international comparisons of mental health outcomes may allow detailed analyses on the differential mental health effects of the pandemic and economic mitigation measures taken by different countries.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.587

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

M.E.N., W.O. and C.D. conceived of the study and obtained funding. M.A. and M.E.N. coordinated the searches, screening and data extraction, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A.S. assisted in writing the first draft of the manuscript, coordinated the presentation of results and assisted in compiling the tables and figures. M.A., M.E.N., W.O., O.S., P.F., E.P., F.A., L.M. and R.C. screened the titles, abstracts and full texts, and conducted data extraction. All authors have critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the manuscript for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided through the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant number 101016233). The funder had no role in the design, completion or writing up of the study.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.