Anxiety disorders and depression are common mental health problems affecting approximately 3.6% and 4.4% of the global population, respectively.1 A significant proportion of these common mental health problems emerge before or during adolescence (51.8% for anxiety disorders and 11.5% for mood disordersReference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo and Salazar de Pablo2). Effective pharmacological and psychological treatments exist,3,4 but their effectiveness is only moderate and do not work for everyone.Reference Roth and Fonagy5 Furthermore, ‘how’ these treatments work and, more specifically, what their ‘active ingredients’ are, remains relatively unclear. The focus of our insight review is on improving communication in families as an active ingredient in the effective treatment of anxiety disorders and/or depression in young people aged 14–24 years. Focus on family communication has historically been rooted in biosocial models of psychopathology, which emphasise that mental health problems are embedded in the individual's social context.Reference Goldberg and Huxley6 On these accounts, relationships, and the communication between individuals within those relationships, are implicated in the aetiology and possible treatment of psychopathology, including anxiety disorders and depression.

Communication is an essential component of human social functioning. To define communication within a family context, we draw on seminal work by Fitzpatrick and Ritchie,Reference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7 who argue that family communication can be understood within the dimensions of ‘openness and emotional accessibility’ and ‘structural traditionalism’. For the purposes of this review, we focus on openness and emotional accessibility, which describes the extent to which family members exhibit ‘openness in deployment of emotional resources, receptivity to new information, and shared responsibility for coping with daily emotion and social crises’.Reference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7 Within this framework, family communication can be measured as the extent to which family members reciprocate feelings to one another, solve problems together and are open to new information without it causing conflict.Reference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7 Indeed, psychometric studies that have developed scales to measure family functioning incorporate the definitions established in this early work.Reference Epstein, Baldwin and Bishop8

Given the ubiquity of communication in human relationships, it has been argued that negative patterns of communication can contribute to the onset of mental health problems, as they exacerbate risk factors that may predispose the individual to psychopathology.Reference Goldberg and Huxley6 LongitudinalReference Baumrind9 and cross-sectional evidenceReference KavehFarsani, Kelishadi and Beshlideh10–Reference Zhang, Pan, Zhang and Lu12 suggests that open and respectful communication between parents and their adolescent offspring reduces the risk common mental health problems. Furthermore, influential developmental models of anxiety and depression implicitly implicate communication. For example, Bowlby's attachment theory assumes that ‘internal working models’ of attachment are generated in the context of goal-corrected partnership with primary attachment figures, where communication of emotional needs is central.Reference Bretherton13 Similarly, cognitive–behavioural models assume that experiences in key relationship influence the development of schemas that influence cognition and emotion. These schemas embed interpersonal experiences, within which communication is likely to be central. Psychological abuse, which is strongly associated with risk for psychopathology, largely involves forms of highly pathological communication on the part of the perpetrator.Reference MacMillan, Fleming, Streiner, Lin, Boyle and Jamieson14

Family systems theory provides arguably the most comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding the role of communication in psychopathology. The theory takes a systemic approach to mental health, placing emphasis on the dynamics within the family system rather than the individual themselves.Reference Watson15 Family systems comprise individuals within the family (e.g. parents or siblings) as well as wider networks that influence family members, including peers, grandparents, colleagues and other environmental factors such as socioeconomic status and school climate.Reference Pfeiffer, In-Albon and Asmundson16,Reference Socha and Stamp17 Within these systems are further subsystems, such as parent–child dyads or sibling dyads. The relationships between individuals within families are influenced in a cyclical manner, such that positive interactions perpetuate positive patterns, whereas negative interactions perpetuate negative patterns. Communication, which we restrict to verbal modes of interaction in the current review, is the means by which patterns of interactions are created, maintained or perpetuated in the family systems framework.Reference Thomas, Priest and Friedman18

Consistent with the family systems framework, empirical evidence has demonstrated that family climate and communication styles are a predictor of depression and anxiety in adolescence.Reference Cardamone-Breen, Jorm, Lawrence, Mackinnon and Yap19–Reference Schrodt, Witt and Messersmith22 Indeed, one study found that a lack of family cohesion was associated with increased risk for any mental health disorder (including depression and anxiety).Reference Cuffe, McKeown, Addy and Garrison23 The mechanisms that link poor family communication to adolescent anxiety and depression are likely to be multifaceted and heterogeneous across individuals.Reference Monroe and Anderson24 For example, poor communication patterns can reduce adolescents’ problem-solving capabilities,Reference Ioffe, Pittman, Kochanova and Pabis21 which may heighten vulnerability to depression via increased rumination.Reference Sun, Tan, Fan and Tsui25 Further, familial discord resulting from poor communication can remove an important support system for the adolescent, as parental support is associated with reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms.Reference Guerra, Farkas and Moncada26,Reference van Harmelen, Gibson, St Clair, Owens, Brodbeck and Dunn27 In contrast, good communication within families has also been demonstrated to be a protective factor in adolescent mental health. For example, positive family communication predicts higher self-esteem in adolescence, which is negatively associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression.Reference Birndorf, Ryan, Auinger and Aten28,Reference Orth, Robins and Roberts29 Moreover, parent–adolescent communication is positively associated with well-being and life satisfaction, but negatively associated with internalising and externalising symptoms.Reference Elgar, Craig and Trites30 Together, these empirical studies suggest that poor family communication is an important and multifaceted risk factor for psychopathology in adolescence.

Another route through which poor communication may increase the risk of poor mental health outcomes is by acting as a barrier to treatment. Parents are often key figures in supporting young people's engagement with mental health services, and the quality of communication between young people and their parents is therefore likely to be crucial in accessing treatment and engaging with the support offered. Parents are often involved in shared decision-making about interventions their child receives,Reference Liverpool, Pereira, Hayes, Wolpert and Edbrooke-Childs31 and qualitative work has identified familial conflict as a barrier to parents and adolescents collaboratively seeking mental health treatments.Reference Smith, Linnemeyer, Scalise and Hamilton32 Further, encouraging parental support for therapeutic treatment improves adolescents’ attendance and adherence to these interventions,Reference Nock and Ferriter33 which may be partly because of the dependence adolescents have on parents for accessing support (e.g. facilitating travel to the treatment siteReference Cunningham, Boyle, Offord, Racine, Hundert and Secord34). As such, good family communication may have general mental health benefits and may enhance the efficacy of other interventions; and, where problems exist, it may be necessary to address family communication before other interventions can be successfully implemented (akin to the need to treat high blood pressure before conducting major surgery).

Rationale for the current study

Despite evidence that family communication is a multifaceted risk and protective factor for depression and anxiety disorders, there is limited understanding of whether interventions can improve communication within families, and whether this has positive implications for adolescents’ mental health. The aim of the current systematic review was to determine in which contexts, and for whom, addressing communication in families appears to work, not work and why. We also aimed to examine factors that may moderate the efficacy of these family-focused interventions (e.g. gender, culture, structure of the family unit, family knowledge of anxiety and depression). Throughout the review, we have worked with experts by experience to co-produce the views presented in this article.

Method

Advisory group involvement

We created two groups of experts by experience: a Young People's Advisory Group (YPAG) and a Parents and Carers' Advisory Group (PCAG). The YPAG comprised four regular members (aged 16–23 years) and met four times for 90 min. The PCAG comprised three regular members and met three times for 90 min. There was one joint 90 min meeting between the PCAG and YPAG. YPAG and PCAG members received £20 per hour for attending meetings, and £15 per hour for work between meetings.

Following our first YPAG meeting, we pre-registered our systematic review with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews ( PROSPERO; identifier CRD42022298719) and followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. The PICO framework (population, intervention, control and outcomes) was used to establish inclusion/exclusion criteria and search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

A study was eligible for inclusion if (a) it was a randomised controlled trial; (b) participants were aged between 14 and 24 years; (c) participants had a diagnosis of anxiety disorder and/or depression, as established by DSM or ICD diagnostic criteria or a validated scale; (d) the study intervention involved family members as well as the young person themselves, and family was broadly defined as parents, carers or guardians, siblings or extended relatives; (e) the study included a control group (e.g. treatment as usual or waitlist); (f) the study reported outcomes relating to family communication (improving communication, specifically verbal communication, was defined in terms of reductions in critical, hostile or isolating interactions, or increases in supportive or warm verbal interactions); and (g) the study was available in full text in the English language in a peer-reviewed journal.

Search strategy

EMBASE, Medline and PsycINFO were searched via the OVID interface, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials database was also searched. Searches were completed on 20 January 2022, combining MeSH and free-text terms for our population (children and adolescents aged 14–24 years), intervention (family-focused interventions for common mental disorders), outcome (family communication) and study design (randomised controlled trials). There were no restrictions on the publication date. The reference lists and citations of included articles were also searched. The full search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.545.

Study selection and data extraction

Identified articles were imported into the online software Rayyan (Rayyan Systems, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; http://rayyan.qcri.org),Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid35 and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (K.N.S. and K.D.) independently screened the titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria with Rayyan. Any disagreements for inclusion were discussed by K.N.S. and K.D., and consensus reached. Full texts were then retrieved and screened for eligibility independently by K.N.S. and K.D., using a form developed in Microsoft Excel (2019, for Windows). Any disagreements for inclusion were discussed and resolved between the two reviewers. A data extraction form (available from P.J.L.) was created in Microsoft Excel and data was extracted independently by K.N.S. and K.D. The following data were extracted:

(a) study characteristics: author, year, country, study design features, recruitment method, allocation method, inclusion/exclusion criteria, follow-up period and sample size;

(b) participant characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis and method of ascertainment;

(c) intervention: description of intervention, duration of intervention, number and length of sessions and family involvement (percentage of total time);

(d) comparison: comparator intervention and characteristics of control group;

(e) outcomes: data collection points, primary family communication outcome and method of measurement, analysis method, main results, missing data and loss to follow-up;

(f) potential moderators: gender, culture, structure of the family unit, family knowledge of anxiety and depression, duration of the intervention and percentage of family involvement;

(g) general: limitations as identified by study author(s) and funding.

All included studies were assessed for risk of bias with the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool.Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron36 The two reviewers assessed studies independently with the Risk of Bias 2 tool, and consensus was reached through discussion.

Data extraction began on 31 January 2022.

Data synthesis

The data available from the included studies were insufficient to support a robust or meaningful meta-analysis. Improving family communication was highly heterogeneous across studies with regards to how interventions attempted to alter patterns of communication and how communication was measured. Therefore, the results of the systematic review were synthesised narratively.

Results

Summary of studies

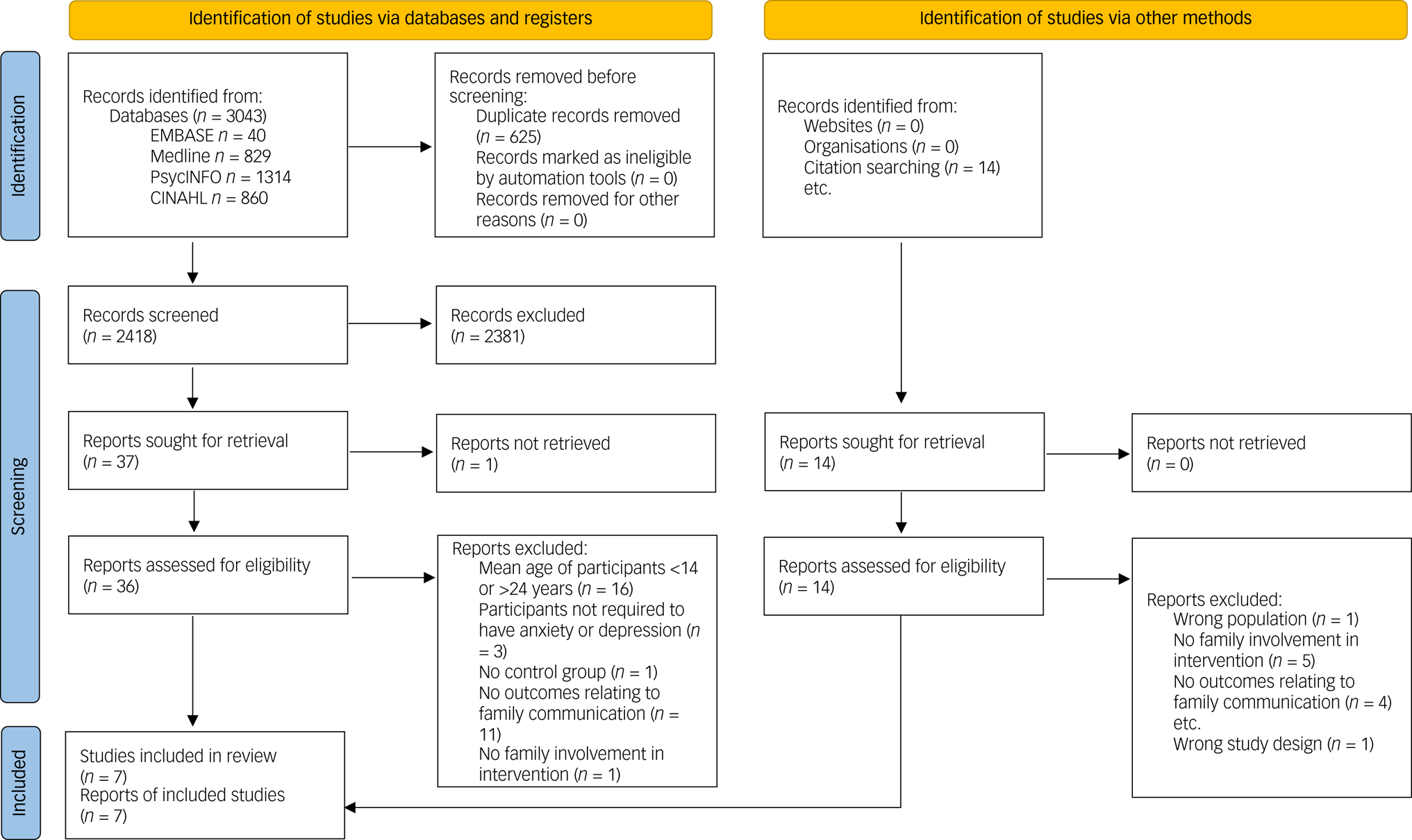

Seven studies met our inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). These studies included 440 participants in total, with a mean age of 15.71 years (note, Bernal et alReference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37 did not report participants’ mean age and was excluded from this calculation). Depression was the primary outcome measure in the studies reviewed; all studies measured depressive symptoms.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37–Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 Five studies additionally measured whether participants met the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (see Table 1).Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37,Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41–Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 Five studies recruited participants from the communityReference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37–Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39,Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41 and two studies recruited participants from out-patient clinics.Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart of systematic literature search.

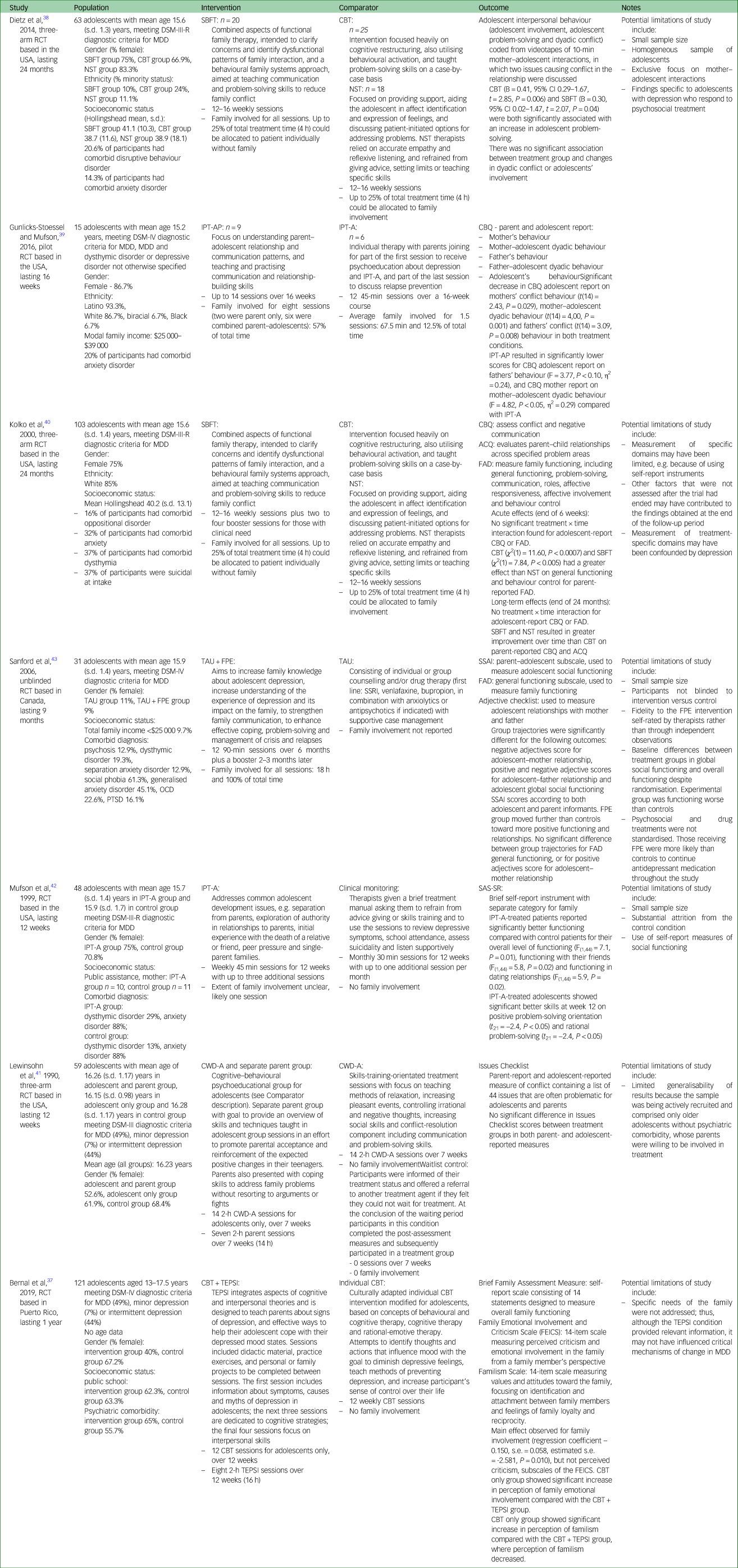

Table 1 Details of the studies examining family communication in context of anxiety and depression included in the current review

RCT, randomised controlled trial; MDD, major depressive disorder; SBFT, systematic behavioural family therapy; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; NST, nondirective supportive therapy; IPT-AP, interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents and parents with depression; IPT-A, individual interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents with depression; CBQ, Conflict Behaviour Questionnaire; ACQ, Areas of Change Questionnaire; FAD, Family Assessment Device; TAU, treatment as usual; TAU + FPE, treatment as usual plus family psychoeducation; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SSAI, Structured Social Adjustment Interview; SAS-SR, Social Adjustment Scale - self-report version; CWD-A, Coping with Depression Course for Adolescents; TEPSI, CBT plus parent psychoeducational intervention; FEICS, Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale.

Five studies included measures of comorbid anxiety.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37–Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40,Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 However, only one study included analyses involving anxiety.Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 There was significant variation in the interventions used to improve family-focused communication across studies, which included systematic behavioural family therapy (SBFT),Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for adolescents and parents with depression,Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39 treatment as usual plus family psychoeducation,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 IPT for adolescents with depression,Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42 coping with depression course for adolescents and a separate parent group,Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41 and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) plus parent psychoeducational intervention.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37 Because of the variation across studies, there was considerable heterogeneity in the structure of the interventions. For example, some interventions only included parents in a single 45 min session,Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42 whereas in others parents attended every session (18 h in totalReference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43).

Effectiveness of family-focused interventions at improving symptoms of anxiety and depression

Several of the studies found evidence that family-focused interventions reduced depressive symptoms (β = 1.02, P < 0.001;Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37 P < 0.001;Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39 P < 0.001;Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41 P < 0.05Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42) and major depressive disorder diagnoses (β = –1.11, P < 0.001;Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37 χ2 = 9.41, P < 0.01;Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41 P < 0.02Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42). However, a caveat is that these studies found similar improvements to depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder diagnosis when using interventions that did not focus on family involvement (Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37; η2 = 0.00, P > 0.10;Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39 major depressive disorder: χ2 = 0.001, P > 0.05Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41) or did not include a comparative intervention.Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42 One study did, however, find that the family-focused intervention led to better parent-reported outcomes on adolescents’ depressive symptoms relative to an intervention without a focus on family communication (P < 0.01Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41), although these differences were no longer present at a 6-month follow-up. In contrast, one study found that an intervention that did not include a focus on family communication was better than an intervention focused on family communication at reducing symptoms of depression (CBT: P = 0.003, SBFT: P = 0.99Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38). A study that compared treatment as usual versus treatment as usual with family psychoeducation found no effect of familial involvement on depressive symptoms or major depressive disorder diagnosis (P = 0.052Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43). Therefore, these studies do not provide clear evidence that family-focused interventions are more effective at improving symptoms of depression relative to interventions without a focus on family communication.

The one study that did include analyses of anxiety symptoms found that CBT was more effective than a family-focused intervention at improving symptoms at a 24-month follow-up.Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40

Key information on family communication measures

The majority of communication measures included in our review were self-report (n = 7); only one measure of communication was recorded by observing interactions between adolescents and their parent. Also, several studies (n = 3) included both adolescent and adult reports of communication. Four studies only included either adolescent or parent reports. The most commonly used measure was the Conflict Behaviour Questionnaire (n = 2), which assesses conflict and negative communication between adolescents and their parents. We recommend future research aims to develop measures that capture the subjective experience of communication, along with objective patterns of communication between family members, and that such measures are completed by both adolescents and their parents.

Do interventions aimed at improving communication work, for whom do they work, in what contexts and why?

Although the studies reviewed provide limited evidence for the effectiveness of family-focused interventions in improving symptoms of anxiety and depression, there was significant variation across studies in how communication was measured and the features of communication treated as outcome measures (Table 1). Although this may reflect the multifaceted way in which we presume communication to affect mental health, this heterogeneity means that we have structured our results to address what features of communication are improved by psychological intervention. Once we have identified the features of communication that are amenable to intervention, we can establish for whom these interventions work, in what contexts and why.

Interventions examining familial involvement

Family involvement describes the degree to which the adolescent feels able to communicate their emotions to their family and the degree to which they perceive their family's communication toward them to be critical. Drawing on Fitzpatrick and Ritchie's conceptualisation of communication in families, this feature of communication could reflect the extent to which families deploy emotional resources toward one another.Reference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7 This feature of communication was examined by three studies,Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37,Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 which provided limited evidence that family-focused interventions improved perceptions of familial involvement. Bernal et alReference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37 found that adolescents assigned to a CBT-only group that did not involve family reported greater family emotional involvement after the intervention, whereas adolescents that completed CBT with additional parent psychoeducation reported no change in family emotional involvement (P < 0.05, effect size 0.77). Two studiesReference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 found that neither SBFT, CBT or nondirective supportive therapy (NST) was associated with changes in familial involvement from pre- to post-intervention. SBFT is a therapy that intends to clarify concerns and identify dysfunctional patterns of family communication, teaching communication and problem-solving skills, whereas NST aims to provide support for adolescents to identify their feelings and consider options to address their issues (see Table 1). However, one studyReference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 found a significant difference in the trajectories of affective involvement, with adolescents who completed treatment as usual plus family psychoeducation reporting greater familial involvement compared with those who only completed treatment as usual (P < 0.05).

Interventions examining problem-solving

Problem-solving reflects the aspect of family communication that describes how the family shares responsibility for solving daily emotional and social crises.Reference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7 Three studies examined adolescents’ problem-solving communication behaviours as outcomes (i.e. behaviours where adolescents generated solutions to interpersonal problems).Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40,Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42 Two studies found that family-focused interventions improved problem-solving abilities relative to interventions without a focus on family involvement (β = 0.30, P = 0.04;Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38 P < 0.05Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42), whereas one study found no difference between interventions with and without a focus on family involvement.Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 Although Dietz et alReference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38 found that completing SBFT improved problem-solving in adolescent–mother dyads relative to CBT and NST, Kolko et alReference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 found no difference between SBFT, CBT and NST on problem-solving immediately after the intervention and at a 24-month follow-up, despite the emphasis in SBFT on teaching problem-solving skills. Notably, Dietz et alReference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38 coded adolescent–mother dyads, whereas Kolko et alReference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 used a self-report measure completed by parents and adolescents. Of note, the findings by Dietz et alReference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38 were rated as having low risk of bias in the measurement of outcomes, whereas Kolko et alReference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 had a high risk of bias in their measurement of outcomes. CBT does, however, include psychoeducational content on problem-solving, which may improve interpersonal problem-solving skills.Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 Although two of the three included studies found evidence that family-focused interventions improved adolescents’ problem-solving skills, these studies suffered from a high overall risk of bias. Therefore, we suggest that the strength of evidence for the effectiveness of family-focused interventions at improving problem-solving skills is weak, based on the studies included in this review.

Interventions examining conflict behaviour

Familial conflict is an aspect of communication that reflects the inverse of receptivity to new information, as described by Fitzpatrick and Ritchie.Reference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7 The four studies examining conflict behaviour between adolescents and their parentsReference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38–Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41 provided mixed evidence regarding the efficacy of family-focused interventions for improving conflict behaviours. Participants who completed IPT for adolescents and parents with depression reported less adolescent–father conflict (reported by adolescents; P < 0.100, η2 = 0.24) and adolescent–mother conflict (reported by mothers; P < 0.050, η2 = 0.29) relative to individual IPT.Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39 Consistent with these findings, parents of adolescents who completed SBFT reported greater improvements to dyadic behaviour compared with parents of adolescents who completed CBT at 24 months follow-up (P < 0.001, χ2 = 12.64Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40), although similar improvements were found for participants who completed NST relative to CBT in this study.Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40 Two further studies did not find a difference between interventions with or without a family-focused component on conflict behaviour.Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41

Interventions examining family functioning

Three studies examined general family functioning,Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 which describes the organisational properties of families and patterns of transactions between family members. For example, measures of general family functioning ask how responsive family members are toward the emotions of other family members, and how accepted the individual feels within the family dynamic.Reference Mansfield, Keitner and Sheeran44 Communication is integral to measures of family functioning, as they focus on verbal ways in which issues are resolved within the family (e.g. talking to people directly rather than going through go-betweens).Reference Epstein, Baldwin and Bishop8 These studies provided limited evidence that family-focused interventions improved general family functioning to a greater extent than interventions without a family-focused component. Although one study found a family-focused intervention improved family functioning relative to NST (χ2 = 12.64, P < 0.007Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40), improvements to general family functioning were similar between treatments with or without a family-focused component.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 Therefore, although family-focused interventions may improve general family functioning, there is an absence of evidence to suggest this improvement is greater than interventions that do not explicitly include families.

Interventions examining social adjustment

Two studies examined social adjustment,Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 which describes the extent to which individuals adjust to social roles (i.e. professional or educational roles, social and leisure activities, and role within the familyReference Gameroff, Wickramaratne and Weissman45). Poor adjustment to social rules can lead to friction, and measures of social adjustment ask how well the individual is able to communicate to others around them in their role (e.g. as the child of their parent).Reference Weissman and Bothwell46 These studies suggested that family-focused interventions were effective at improving adolescents’ social adjustment, as both studies reported greater social functioning scores after completing a family-focused intervention compared with treatment as usual (d = 0.93–0.96Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43) or clinical monitoring (P = 0.01Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42). However, these studies did not compare a family-focused intervention to another psychotherapeutic intervention. Therefore, although family-focused interventions appear successful at improving social adjustment, we cannot assess whether they are more successful than other types of interventions.

Discussion

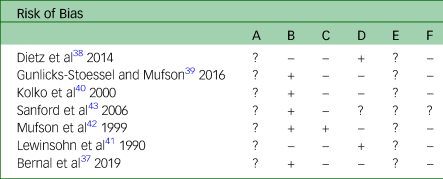

The current systematic review examined the efficacy of family-focused interventions to improve communication within families for adolescents with anxiety disorders and/or depression. Across the seven studies reviewed, we found mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of family-focused interventions to improve any facet communication within families, at least compared with existing interventions that do not include families within the intervention. Yet, we were struck by the absence of high-quality research into improving communication in families of young people with anxiety disorders and/or depression. Our systematic literature search yielded a small number of highly heterogeneous studies, which, despite being randomised controlled trials, had a high risk of bias (Table 2).Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron36 Therefore, in answer to the question, ‘Do family-focused interventions improve communication within families, for whom does this work, in what contexts, and why?’, our team of experts by lived experience, researchers and clinicians suggest that there is insufficient evidence to provide an authoritative answer to this question and encourage further research on this important topic.

Table 2 Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool

A represents bias arising from the randomisation process, B represents bias owing to deviations from intended interventions, C represents bias owing to missing outcome data, D represents bias in measurement of the outcome, E represents bias in selection of the reported result and F represents overall bias.

Do family-focused interventions improve communication within families within context of anxiety disorders and depression?

We found substantial variation in the ways in which family communication was conceptualised (as conflict, family functioning, familial involvement or problem-solving). This heterogeneity prevented us from drawing firm conclusions about whether improving family communication is an active ingredient in the treatment of anxiety disorders and/or depression in 14- to 24-year-olds. However, most of the studies found that family-focused interventions did not lead to significant improvements in features of communication relative to existing psychotherapeutic interventions. Although this could be interpreted to suggest that family-focused interventions do not improve communication, we instead propose that in context of the significant limitations of the included studies (which we discuss below), there is insufficient evidence to conclude whether family-focused interventions can improve communication within families. Indeed, this perspective was reflected by our advisory group, who all agreed that communication within families was a topic worthy of further study in the context of anxiety disorders and depression. There was some promising evidence that communication can be improved (relative to treatment as usual/waitlist), but the mixed findings, heterogeneous measurement and non-specificity of the results (e.g. compared with other treatments) make it impossible to recommend an approach to improving communication at this stage.

For whom do family-focused interventions work?

We believe that a conceptual shift is required to advance our understanding of for whom improving communication in families works. The analogy from physical health – of the accepted importance of addressing high blood pressure – is useful here in at least two ways. First, high blood pressure is itself a risk factor for other health problems (such as hardened arteries, which, in turn, are a risk factor for heart failure). Second, effective treatment of high blood pressure can be a pre-requisite for other medical interventions to be conducted safely (such as before elective surgery). Ineffective communication might similarly be a non-specific risk factor for common mental health problems, as indicated by the multifaceted way in which studies have linked poor family communication to mental health outcomes,Reference Schrodt, Witt and Messersmith22,Reference Cuffe, McKeown, Addy and Garrison23,Reference van Harmelen, Gibson, St Clair, Owens, Brodbeck and Dunn27,Reference Smith, Linnemeyer, Scalise and Hamilton32 and therefore may be an appropriate target for prevention. Further, for interventions to be effective, communication within families might need to be addressed as a pre-requisite for some individuals. For example, as one of the members of our YPAG stated ‘effective communication is really important. Without it, young people, who may require only very minimal support to reduce their anxiety, can't get that fulfilled’. Indeed, the inability to express the need for support is consistent with empirical evidence that poor communication with parents can create a barrier to the access of treatment.Reference Cunningham, Boyle, Offord, Racine, Hundert and Secord34

In what context do family-focused interventions work?

We are also unfortunately unable to draw conclusions about how to best target communication in psychological therapy. There was significant heterogeneity in the interventions used to deliver family-focused content (including CBT, family psychoeducation, IPT for adolescents with depression and SBFT) and often embedded in programmes with significant additional content. A number of these interventions are time-limited and highly structured, established for individual delivery rather than delivery to adolescent with their parents (e.g. CBT, IPT for adolescents with depression). As such, we raise the question of whether content aimed at improving communication should be integrated within, and therefore potentially replace or shorten, existing treatment programme elements or be the focus of a separate and distinct intervention; and, in either case, how should this be practically implemented?

Four studies in our review included a family-focused component to an intervention that traditionally did not involve family members.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37,Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39,Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 Of these studies, only one found the addition of the family-focused intervention improved communication (specifically conflict behaviourReference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39). In this study, an adaption of IPT for adolescents with depression was delivered with parents attending several sessions. Given the existing emphasis of IPT for adolescents with depression on communication,Reference Young, Mufson and Davis47 it may be that some treatments are more amenable to the inclusion of family-focused content compared with interventions that focus on other mechanisms of change (e.g. cognitive restructuring in CBT). Indeed, the missed potential for family-focused interventions to benefit adolescents was highlighted by one study that found participants in classical CBT reported greater feelings of family emotional involvement compared with participants in CBT supplemented with a family-focused component.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37 One interpretation of this finding is that increased parental involvement following a family-focused intervention may be incongruent with adolescents’ desire for increased autonomy from caregivers,Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi, Wickremarathne and Patton48 producing adverse outcomes. Certainly, care needs to be taken with adding elements to existing evidence-base interventions, as it may inadvertently reduce the therapy's effectiveness by incurring a kind of opportunity cost. Furthermore, a key question that we hoped to address but could not, is when a focus on communication might be indicated or not; further research is urgently needed to establish this.

Strengths and limitations

The included studies were all randomised controlled trials, with all but oneReference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 utilising blinded allocation to the treatment condition when compared with a control condition. Furthermore, three studies compared the family-focused intervention to another intervention and a control condition,Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Kolko, Brent, Baugher, Bridge and Birmaher40,Reference Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops and Andrews41 which provided stronger evidence for the efficacy (or lack thereof) of family-focused interventions.

However, we also identified several limitations in the studies reviewed. Of critical importance is the small sample size in half of the studies included in the review,Reference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38,Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39,Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel42,Reference Sanford, Boyle, McCleary, Miller, Steele and Duku43 meaning these studies most likely did not have statistical power to identify differences between treatment arms. Furthermore, there was a disproportionate focus on adolescent–mother dyads, either because of an explicit design choiceReference Dietz, Marshal, Burton, Bridge, Birmaher and Kolko38 or fathers not attending as often.Reference Bernal, Rivera-Medina, Cumba-Avilés, Reyes-Rodríguez, Sáez-Santiago and Duarté-Vélez37,Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel and Mufson39 If the reason for poor family communication was a result of adolescent–father conflict, this could be one possible explanation for the absence of evidence regarding the efficacy of family-focused interventions at improving communication. This view was endorsed by our advisory group who suggested that it is the ‘underlying dynamics [of the family] that need to be looked at’.

Finally, our focus was limited to children and young people with diagnoses of anxiety disorders and/or depression as part of the project to assess active ingredients in the treatment of these disorders.Reference Wolpert, Pote and Sebastian49 Thus, we were unable to examine the importance of addressing family communication in the face of a more general sense of severe emotional distress. This important issue was emphasised by our experts by lived experience:

‘… it was clear that there was more emotional distress that went unrecognised and untreated [in child and adolescent mental health services]. It wasn't until DBT [dialectical behaviour therapy] skills were offered at aged 18+ (in adult services), which directly addressed communication skills, that both my daughter and I benefitted from greatly improved communication.’

Recommendations for policy makers, clinicians and funders

In the light of our findings, the theoretical and practical importance of communication, and our advisory group discussions, we call for funders to prioritise studies that will develop measures that capture essential features of communication. One such feature, emphasised by our experts by lived experience, is that ‘Communication is not clear cut, straightforward, it can be a way of connecting, rather than a way of putting some message across.’ Thus, affective dimensions like connection must be captured in addition to definitions that rely on the transmission of information. We do not expect this to be simple. Indeed, as another expert by experience explained, ‘Effective communication is more than just exchanging information. It's about understanding the emotions and intention behind the information. That's the bit that's hard to measure. There's much more going on, especially in families.’ Consistent with this view, empirical studies have demonstrated that discrepancies between the adolescent's and parents’ perceptions of the effectiveness of their communication with one another are associated with greater internalising problems.Reference Kapetanovic and Boson50 Therefore, the objective act of exchanging information may not be sufficient to measure communication. Rather, we propose that measures should be developed that capture the affective experience of connecting through verbal exchanges to examine communication within families.

In conclusion, it is important to acknowledge limitations of the current systematic review. Although our definition of family communication was guided by theoretical work on this topicReference Fitzpatrick and Ritchie7,Reference Pfeiffer, In-Albon and Asmundson16 and was endorsed by our advisory group of lived experience experts, these theoretical definitions did not map exactly onto the outcome measures used in the included studies. Indeed, this issue further emphasises the need for the development of new tools to measure family communication that reflect both theory and the lived experience of communication within families.

Communication is of central theoretical and practical importance to young people's mental health, yet we have found an absence of evidence about the role of improving family communications as an active ingredient in the treatment of anxiety and/or depression in young people aged 14–24 years. As a team of clinicians, experts by experience and scientists, we call for future studies to be designed to conceptualise communication more rigorously, to capture young people's lived experience of what communication is; to identify how to improve communication within families and to better understand for which young people and families this will be most beneficial. As stated by a member of our advisory group:

‘If you get it wrong at the foundational stage, if young people don't feel that they can speak openly and be heard and validated for their experiences, then that's a really shaky start and where do you get that if it doesn't start in the family home?’

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.545

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, P.J.L., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the McPin Foundation for their assistance in creating the Young People's Advisory Group and the Parents and Carers' Advisory Group.

Author contributions

A.T., K.D., K.N.S., P.F., P.J.L., the Young People's Advisory Group and the Parents and Carers’ Advisory Group were responsible for study conception and data acquisition. A.T., A.L., K.D., K.N.S., P.F., P.J.L., the Young People's Advisory Group and the Parents and Carers’ Advisory Group were responsible for data analysis and interpretation, drafting and reviewing the manuscript, final approval of the manuscript and accountability.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust Mental Health Priority Area Active Ingredients Commission, awarded to P.J.L. at University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report or decision to submit manuscript.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.