Over the past decade, clinical practice guidelines in schizophrenia care have proliferated in numerous countries. The key objective is to ensure a high and standardised quality of care by recommending a set of evidence-based interventions to articulate systematic approaches and best-practice models. Reference Lehman, Lieberman, Dixon, McGlashan, Miller and Perkins1–4 Despite various efforts to ensure efficacious implementation, evidence indicates that treatment offered in routine clinical practice often fails to meet guideline recommendations. Reference Lehman and Steinwachs5–Reference Dickey, Normand, Hermann, Eisen, Cortes and Cleary10 Thus, patients with schizophrenia may receive limited evidence-based practices resulting in inadequate improvements in patient care and clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of population-based data on the implementation of practice guidelines in schizophrenia care. In Denmark, the quality of care for patients with schizophrenia has been systematically monitored and continuously audited since 2004 in The Danish Schizophrenia Registry, a national multidisciplinary quality improvement initiative. We conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study to examine whether the quality of care, as reflected by the adherence to specific processes of care among Danish patients hospitalised with schizophrenia, has improved since the initiation of The Danish Schizophrenia Registry.

Method

The Danish healthcare system is a public, mainly tax paid healthcare system that provides free access to hospital care for all Danish residents. 11 If hospitalisation is required, patients with schizophrenia are exclusively treated at public psychiatric hospitals. Each patient contact with the healthcare system is recorded in administrative and medical registers using the patient's unique, ten-digit civil registration number to ensure monitoring and regulation of the healthcare system. Reference Pedersen, Gotzsche, Moller and Mortensen12

The Danish Schizophrenia Registry

The Danish Schizophrenia Registry was established with the objective of monitoring, documenting and improving diagnosis and quality of care among patients with schizophrenia and was operative from 2004 onwards. It is mandatory for all Danish psychiatric hospitals, units and relevant clinical departments treating patients with schizophrenia to report data on all in-patients and out-patients with schizophrenia to the registry. The registry contains information on whether key recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and care of patients with schizophrenia are followed as reflected by the use of specified processes of care. Reference Mainz, Hansen, Palshof and Bartels13–Reference Mainz, Krog, Bjornshave and Bartels15 The following areas are assessed: diagnosing schizophrenia, antipsychotic medical treatment, metabolic syndrome, family intervention, psychoeducation, suicide risk assessment at discharge and post-discharge support. These areas are covered by a total of 16 processes of care which reflect to what extent recommended evidence-based interventions according to the national practice guidelines are implemented in the psychiatric departments. The processes of care were identified by a multidisciplinary expert panel of physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists representing national scientific societies and professional organisations. 4,Reference Mainz, Hansen, Palshof and Bartels13 The registry also contains information on prognostic factors including: gender, age, abuse (alcohol, substances, benzodiazepines or cannabis), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale to evaluate the overall psychosocial functioning of a patient. The scale ranges from 1 to 100, with 1 representing the poorest functioning and 100 representing the best functioning. Reference Moos, McCoy and Moos16,Reference Hilsenroth, Ackerman, Blagys, Baumann, Baity and Smith17 In this context, the functioning scale (GAF-F) from the split version is used. All data are prospectively collected using a registration form with detailed instructions. For in-patients with schizophrenia, the processes of care are registered at the time of discharge from the psychiatric department by the healthcare professionals responsible for the care of the individual patient. For long-term in-patients, the processes of care are registered once a year on the date of admission.

Of the total 16 specific processes of care, The Danish Schizophrenia Registry monitors 10 processes of care relevant to in-patients with schizophrenia, which are exclusively assessed in this study. 14 Table 1 lists the definitions of the 10 processes of care. During the study period, the set of processes of care was subject to several changes as some processes of care were added whilst others were omitted. Thus, the time periods for the different processes of care varied, which was taken into account in the data analyses. Assessment of psychopathology by a specialist in psychiatry, assessment of psychopathology using a diagnostic interview, assessment of cognitive function and assessment by a social worker were processes of care only applied for incident patients. In 2010, psychoeducation was likewise changed to include incident patients only. Contact with relatives and psychoeducation were only assessed in patients for whom the healthcare professionals considered the specific processes of care to be beneficial and relevant. A minimum contact with relatives was defined as a phone call or a personal meeting. The remaining processes of care were a priori considered relevant for both incident and prevalent patients.

Table 1 Definitions of the processes of care for in-patients with schizophrenia

| Processes of care | Definition |

|---|---|

| Assessment of psychopathology by a specialist in psychiatry | Indication of whether the incident patient has been assessed for psychopathological characteristics by a specialist in psychiatry |

| Assessment of psychopathology using a diagnostic interview | Indication of whether the incident patient received a diagnostic interview with an established interview instrument, such as the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry or the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychosis |

| Assessment of cognitive function | Indication of whether the incident patient went through a cognitive test performed by a psychologist |

| Assessment by a social worker | Indication of whether the incident patient was assessed for need of social support by a social worker, such as financial help to purchase medicine, help with changing housing or application for disability benefits |

| Antipsychotic medical treatment | Indication of whether the patient was prescribed antipsychotic medical treatment |

| Contact with relatives | Indication of whether the patient's relatives had contact with the staff |

| Psychoeducation | Indication of whether the patent received psychoeducation |

| Post-discharge professional support | Indication of whether patients with a GAF-F score ≤30 were referred to post-discharge professional support in the patient's own home, residential facilities or care homes |

| Psychiatric aftercare | Indication of whether the patient was referred to psychiatric aftercare, including out-patient treatment, contact to general practice or a private specialist after discharge |

| Suicide risk assessment | Indication of whether the patient was assessed for suicide risk in the week leading up to the discharge, including an evaluation of depressive symptoms |

Study population

The study population included all patients (≥18 years old) admitted to hospital with schizophrenia and recorded in The Danish Schizophrenia Registry between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2011. Schizophrenia was defined according to the International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10) F20.0 to F20.99. 18 The study included only in-patients (not out-patients), including incident, prevalent and long-term in-patients with schizophrenia. Incident patients with schizophrenia were defined as individuals who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia within the last 12 months. We only included patients with the first recorded date of discharge from a psychiatric department during 2004–2011, leaving a total of 14 228 patients admitted to 229 different psychiatric departments to be included in the analyses.

Statistical analyses

A descriptive analysis was performed, including the distribution of patient characteristics and the adherence to processes of care according to the year of admission. The adherence to processes of care was assessed both overall and for each process of care separately. The overall quality of schizophrenia care was calculated by dividing the number of received processes of care with the number of relevant processes of care for the individual patient. Furthermore, the overall quality of care was assessed for each psychiatric department. Missing and irrelevant data were excluded from the calculation of the adherence to each process of care separately.

Changes in the adherence to each process of care was examined using binary regression to calculate the relative risk (RR) using relevant time periods as reference (i.e. the year of the adherence to each process of care was first assessed in the registry). All 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were corrected for clustering of patients within psychiatric departments using robust estimates of the variance. A two-sided P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered to be significant. STATA (version 11.2 special edition) was used for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive data on the study population are summarised in Table 2. Men were overrepresented in the study population and the majority of the patients were aged 18 to <50 years. More than one-third of the patients had a GAF-F score <40, indicating dysfunction in several areas. Finally, 37% of the patients had comorbid substance abuse of alcohol, illegal drugs or benzodiazepines.

Table 2 Characteristics of incident and prevalent patients hospitalised with schizophrenia between 2004 and 2011

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total | 14 228 (100) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 5734 (40) |

| Men | 8494 (60) |

| Age | |

| 18 to <30 years | 3853 (27) |

| 30 to <40 years | 3471 (24) |

| 40 to <50 years | 3340 (24) |

| 50 to <60 years | 2167 (15) |

| ≥60 years | 1397 (10) |

| Abuse: alcohol | |

| No | 9385 (66) |

| Yes | 3522 (25) |

| Unknown | 1321 (9) |

| Abuse: substances | |

| No | 11 069 (78) |

| Yes | 916 (6) |

| Unknown | 2 243 (16) |

| Abuse; benzodiazepine | |

| No | 11 407 (80) |

| Yes | 898 (6) |

| Unknown | 1923 (14) |

| Abuse: cannabis | |

| No | 9648 (68) |

| Yes | 3136 (22) |

| Unknown | 1444 (10) |

| GAF-F score | |

| 0 to <30 | 1326 (9) |

| 30 to <40 | 4147 (29) |

| 40 to <50 | 3537 (25) |

| 50 to 100 | 2972 (21) |

| Unknown | 2246 (16) |

Figure 1 presents the adherence to processes of care both overall and separately according to year of admission between 2004 and 2011. The overall adherence to processes of care, reflecting the proportion of all relevant recommended processes of care delivered to the patients, increased from 64 to 76% between 2004 and 2011. In addition, online Table DS1 shows the changes in the adherence to the ten processes of care separately according to year of admission between 2004 and 2011. As shown in Table 3, the adherence to a number of processes of care increased between 2004 and 2011, including assessment of psychopathology using a diagnostic interview from 34 to 68% between 2005 and 2011 (RR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.51–2.68), contact with relatives from 47 to 67% between 2004 and 2011 (RR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.27–1.62), psychoeducation from 56 to 74% between 2004 and 2009 (RR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.19–1.48), psychiatric aftercare from 85 to 90% between 2005 and 2011 (RR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01–1.11) and finally suicide risk assessment from 72 to 95% between 2005 and 2011 (RR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.21–1.42). Improvements over time were, however, not found for the remaining assessed processes of care. In contrast, post-discharge professional support declined from 95 to 86% between 2005 and 2011 (RR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84–0.99).

Fig. 1 The proportion of in-patients with schizophrenia receiving recommended processes of care both separately and overall between 2004 and 2011.

*Receiving all relevant recommended processes of care.

Table 3 Adherence to processes of care separately among patients hospitalised with schizophrenia between 2004 and 2011

| Processes of care (time period recordings) | Entire time period recording, % received (n patients) | First year of recording, % received (n patients) | Last year of recording, % received (n patients) | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of psychopathology by a specialist in psychiatry (2004–2011) | 92 (3070) | 94 (329) | 93 (405) | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) |

| Assessment of psychopathology using a diagnostic interview (2005–2011) | 53 (2157) | 34 (256) | 68 (358) | 2.01 (1.51–2.68) |

| Assessment of cognitive function (2004–2011) | 36 (2908) | 29 (326) | 38 (353) | 1.34 (0.89–2.00) |

| Assessment by a social worker (2004–2011) | 85 (2987) | 82 (335) | 84 (383) | 1.02 (0.95–1.11) |

| Antipsychotic medical treatment (2004–2011) | 96 (13 378) | 97 (2872) | 96 (1192) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) |

| Contact with relatives (2004–2011) | 57 (11 107) | 47 (2369) | 67 (947) | 1.44 (1.27–1.62) |

| Psychoeducation (2004–2009) | 64 (10 846) | 56 (2774) | 74 (1267) | 1.33 (1.19–1.48) |

| Post-discharge professional support (2005–2011) | 89 (1212) | 95 (188) | 86 (192) | 0.91 (0.84–0.99) |

| Psychiatric aftercare (2005–2011) | 87 (9018) | 85 (1439) | 90 (1044) | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) |

| Suicide risk assessment (2005–2011) | 86 (8404) | 72 (1188) | 95 (1099) | 1.31 (1.21–1.42) |

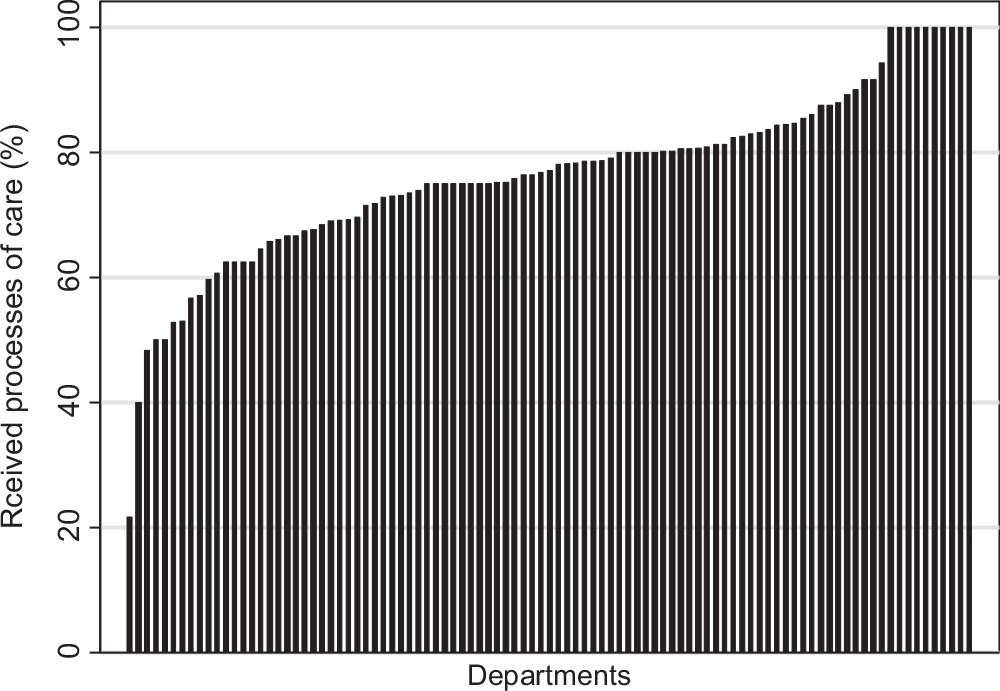

Figure 2 illustrates the overall quality of schizophrenia care, reflecting the proportion of all relevant recommended processes of care delivered in 2011 in the individual departments. As shown in the figure, substantial variation in the overall quality of care remains among psychiatric departments treating patients with schizophrenia. The proportion of delivered recommended processes of care varied between 22 and 100% across the departments.

Fig. 2 The overall quality of care delivered at 229 departments for in-patients with schizophrenia in 2011.

Discussion

Our study showed improvements in the overall quality of care delivered to patients hospitalised with schizophrenia in Denmark between 2004 and 2011. Furthermore, we observed increased adherence to specific guideline recommended processes of care, including assessment of psychopathology using a diagnostic interview, contact with relatives, psychoeducation, psychiatric aftercare and suicide risk assessment. However, increasing adherence over time was not observed for all assessed processes of care and considerable variation in the overall quality of care remains among Danish psychiatric departments treating patients with schizophrenia.

Strengths and limitations in the study

The strengths of this study include the nationwide population-based design with prospectively collected data and a relatively large study population. The Danish Schizophrenia Registry has a high coverage; for example, it has been estimated to include records for >90% of all in-patients with schizophrenia in the Danish psychiatric healthcare system. 14 The high completeness of patient registration indicates that the study population is likely to be representative for the entire in-patient population of patients with schizophrenia in Denmark. Confounding is considered to be of minor importance for the study findings as the ten included mental healthcare processes in principle are relevant for hospitalised patients independent of time periods, patient characteristics and psychiatric departments.

Data validity is always a relevant concern in registry-based studies and this is obviously also the case in this study. The data in The Danish Schizophrenia Registry are collected by a large number of clinicians during routine clinical work, and registration errors and variation in registration practice may occur. However, extensive efforts are made to ensure the validity of data by designating key persons in each psychiatric department with the responsibility of securing correct data collection and reporting. In addition, uniformity and validity are ensured by detailed instructions with explicit data definitions in standardised registration forms and regular structured audit processes carried out on a local, regional and national basis. The audit processes critically assess the quality of the data and provide continuous feedback to the psychiatric departments. 14 It must, nonetheless, be noted that recent findings indicate inconsistency in the documentation practices in Danish psychiatric hospitals. Insufficient medical records for patients with schizophrenia may prevent the use of psychiatric medical records as the gold standard when validating registry data. Reference Pedersen, Gradus, Johnsen and Mainz19

Comparison with other studies

Our findings indicate that the adherence to guideline recommended processes of schizophrenia care has increased in several areas of care following the initiation of The Danish Schizophrenia Registry. Population-based data on the implementation of practice guidelines in schizophrenia care elsewhere are sparse and none has assessed changes in the quality of care over time. Nevertheless, our findings that patients were more likely to be prescribed antipsychotic medical treatment and less likely to receive recommended psychosocial care is supported by other non-population-based studies. An American study examined the conformance of treatment patterns in schizophrenia care with evidence-based recommendations in a random sample of 719 patients from routine care settings in two states. Reference Lehman and Steinwachs5 The recommendations addressed five major treatment categories including psychological interventions, family interventions, pharmacotherapy, vocational rehabilitation and assertive community treatment/assertive case management for both in-patients and out-patients. The conformance rates to most of the recommendations were generally below 50%. Furthermore, the rates of conformance were overall lower for recommendations in psychosocial treatment than for pharmacological treatment. Similar findings are reported in studies assessing the implementation of practice guidelines in schizophrenia care. Reference Addington, McKenzie, Smith, Chuang, Boucher and Adams6–Reference Dickey, Normand, Hermann, Eisen, Cortes and Cleary10 Nonetheless, most of the studies were cross-sectional studies and none assessed the impact of initiatives aimed at implementing practice guidelines. Furthermore, diversity between the methods of assessing adherence, study populations and definitions of practice guideline recommendations makes direct comparisons difficult.

In this study, substantial variation between the psychiatric departments was demonstrated in the overall quality of care even after 7 years of monitoring, documenting and regularly auditing in The Danish Schizophrenia Registry. The results indicate insufficient implementation of practice guideline recommendations at specific departments. In this case, several underlying mechanisms, including diversity in the organisational structure of the psychiatric departments, healthcare professional skills and available resources, may possibly explain the observed variation in the overall quality of care. A variety of barriers in the physician adherence have been identified to potentially undermine the implementation of clinical practice guidelines including lack of knowledge or awareness to the guideline, lack of agreement or motivation to follow the guideline and lack of time or resources to actually implement the guideline recommendation. Reference Cabana, Rand, Powe, Wu, Wilson and Abboud20 In addition, the support of the top leadership, the professional culture and motivation may play a significant role in implementing practice guideline recommendation. The observed variation between the psychiatric departments may also, to some extent, be explained by inconsistency in the documentation practices in Danish psychiatric hospitals. Reference Pedersen, Gradus, Johnsen and Mainz19

We observed improvements over time in the diagnostic process, contact with relatives, psychoeducation, psychiatric aftercare and suicide risk assessment. A contributing factor for the improvements in the psychiatric aftercare at least in a Danish context may be the establishment of the Danish specialised assertive intervention programme (OPUS) in 2004. Reference Nordentoft, Melau, Iversen, Petersen, Jeppesen and Thorup21 The OPUS deals with early detection and assertive community treatment of patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders and comprises a 2-year treatment including intensive psychosocial assertive community treatment, family treatment, social skills training, multifamily groups and psychoeducation. A designated primary staff member is responsible for maintaining contact and coordinating the treatment across involved institutions and social services. Reference Bertelsen, Jeppesen, Petersen, Thorup, Ohlenschlaeger and le Quach22 Studies show that the OPUS improved patients’ adherence to treatment as well as clinical outcome, including improved effects on negative and psychotic symptoms, a higher treatment satisfaction, reduced secondary substance abuse and lower dosage of antipsychotic medication after 2 years of treatment. Reference Petersen, Jeppesen, Thorup, Abel, Ohlenschlaeger and Christensen23,Reference Petersen, Thorup, Oqhlenschlaeger, Christensen, Jeppesen and Krarup24 The increased focus and greater demands to the treatment and intersectoral transitions of patients with schizophrenia due to the OPUS treatment may correlate with the improvements over time in this study. Various factors, besides the OPUS, may potentially have contributed to the improved quality of care among patients hospitalised with schizophrenia. In 2004, The Danish Healthcare Quality Programme was initiated to support continuous quality development in the Danish healthcare system by means of accreditation standards. The programme facilitated a wide focus on both healthcare services as well as coherent pathways across units and sectors. 25 A further major structural reform of the Danish healthcare system took place in 2007 to secure high quality and patient safety by weighting quality higher than geographical closeness to the nearest hospital. Reference Christiansen26 The establishment of The Danish Schizophrenia Registry ensures continuous monitoring of the adherence to guideline recommended processes of care and is supplemented by regular audits and feedback to the individual psychiatric department. 14 Such initiatives may further ensure commitment and active involvement of the clinicians over time.

The adherence to certain processes of care remained stable in our study; however, it should be noted that a high adherence to practice guideline recommendations for some of the assessed processes of care (e.g. use of antipsychotics) already from the time of the launch of the registry precluded substantial improvements. There is so far no strong scientific evidence documenting the effect of psychosocial processes of care including assessment of cognitive function and social support by a social worker and patient outcome. As a result, these processes of care may potentially be prioritised lower in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia in comparison with pharmacological treatment. The clinical uncertain effectiveness may, however, not be the only explanation of the stable adherence. In some cases, the processes of care may also not have been prioritised by clinicians simply because the patients did not have obvious cognitive dysfunctions or complex social needs. Interestingly, receiving of post-discharge professional support decreased over time. The explanation for this statistically significant decrease is not clear; however, the examined population of patients with a GAF score ≤30 was quite small which potentially could lead to a moderate statistical precision in the analyses on this process of care. If this finding genuinely reflects less probability of receiving post-discharge professional support, this points to the importance of monitoring adherence to such processes of care, as social support is highly important to the level of functioning, quality of life and the ability to engage in social and occupational activities. Reference Bertelsen, Jeppesen, Petersen, Thorup, Ohlenschlaeger and le Quach22,Reference Barry and Crosby27

We encourage further studies of the effectiveness of quality of psychiatric care improvement strategies and in particular initiatives aimed at improving the implementation of practice guideline recommendations.

In conclusion, this nationwide population-based cohort study demonstrated that the adherence to guideline recommended processes of care increased between 2004 and 2011 among Danish patients admitted to hospital with schizophrenia.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.