Over the past few decades, numerous studies have reported that religion and spirituality are generally associated with better coping skills and positive health indicators, particularly with respect to mental health.Reference Koenig, McCullough and Larson 1 , Reference Koenig, King and Carson 2 Religion/spirituality has been associated, for example, with lower rates of suicide, depression, anxiety, and substance misuse, better recovery in cases of depression and greater overall well-being.Reference Koenig, McCullough and Larson 1 – Reference Bonelli and Koenig 4

Based on these growing number of studies supporting the relevance of religion/spirituality, medical organisations, among them the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych), the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and more recently the Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria (Brazilian Association of Psychiatry – ABP), have created specific committees to handle matters related to the inclusion of religion/spirituality in clinical practice, as well as in medical training and the continuing education of doctors on this subject. The WPA has recently published its ‘Position Statement on Spirituality and Religion in Psychiatry’ which acknowledges the importance of considering the spiritual dimension in psychiatric training, research and clinical practice. 5 – Reference Moreira-Almeida, Sharma, Rensburg, Verhagen and Cook 8

In response to the increased importance of religion/spirituality in clinical practice, further research has been carried out, with the purpose of investigating the religious and spiritual profiles of psychiatrists and their attitudes towards including religion/spirituality into the management and care of their patients.Reference Neeleman and King 9 – Reference Lawrence, Head, Christodoulou, Andonovska, Karamat and Duggal 14 What was interesting to observe from those studies was that the majority of psychiatrists agree on the importance and the need to integrate religious/spiritual aspects in clinical practice.Reference Neeleman and King 9 , Reference Baetz, Griffin, Bowen and Marcoux 10 , Reference Lawrence, Head, Christodoulou, Andonovska, Karamat and Duggal 14

Owing to the lack of information about how Brazilian psychiatrists deal with religion/spirituality, the present work attempts to assess their current view on religion/spirituality, both with regard to their own religious and spiritual profile as well as the assessment of their patients’ religion/spirituality in their clinical practice, and whether there is any relationship between these areas. Apart from being the first systematic evaluation into religion/spirituality in psychiatric practice to be carried out in Brazil, where ethnic, cultural and religious diversity increases the need for studies and programmes capable of allowing professionals to better care for patients in such a diverse sociocultural context, the results will give support to new policies to improve health education, management and prevention in psychiatry.

Method

Design of the study, sampling and procedures

This was a cross-sectional study of 3120 psychiatrists belonging to the ABP who were emailed information on the study and invited to participate by completing a confidential online questionnaire.

In order to optimise the return rate, the emails were re-sent, emphasising the limited period for data collection and the importance of their participation. The emails were sent between 12 September 2013 and 6 February 2014, and up to 10 times to the psychiatrists who did not respond.

Measurements

The survey presented in this study was based on the questionnaire Religion and Spirituality in Medicine: Doctors’ Perspectives developed by Curlin et al,Reference Curlin, Lawrence, Chin and Lantos 15 which evaluates doctors’ religious/spiritual characteristics and their influence, if any, on clinical practice and their patients’ health. The survey was adapted and translated into Portuguese by one of the authors (M.F.P.P.) and revised by another (M.C.M.-C.). It consists of self-reported questions to assess the following three main areas.

Sociodemographic and professional features

The data included age, gender, marital status, location, degree level, specialty within psychiatry and length of professional experience.

The participants’ religious and spiritual features

The psychiatrists were questioned about their beliefs in God or a superior power and about religious affiliation. The response categories were Catholic, Spiritist, Protestant or Evangelical, other religion (includes Jewish, Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Mormon and others) and none (includes agnostic, atheist and none), which were later coded as a binary variable (with or without religious affiliation).

Two questions measured to what extent the participants considered themselves to be spiritual or religious. The questions, ‘to what extent do you consider yourself to be a spiritual person?’ and ‘to what extent do you consider yourself to be a religious person?’ had four possible responses: not at all, slightly, moderately, very religious and/or spiritual. We did not define the terms religion and spirituality, we allowed the respondents to apply their own definitions. However, the participants were asked questions to distinguish between their religion and their spirituality.

Opinions and behaviours related to religion/spirituality and the approach to religion/spirituality in clinical practice and in medical training

Regarding their opinions related to the role of religion/spirituality in clinical practice, the psychiatrists were asked whether they considered it important to integrate their patients’ religious and spiritual aspects into clinical practice. The question had four possible responses: not, a little, reasonably and very important. The categories ‘reasonably important’ and ‘very important’ were grouped to identify those who considered it important to integrate religion/spirituality into clinical practice.

Concerning the approach to religion/spirituality in clinical practice, the participants were asked how often they enquired about their patients’ religious/spiritual issues. The four possible responses were never, rarely, occasionally and frequently. A binary variable was created to identify those who did this frequently (yes = frequently and no = occasionally + rarely + never).

Regarding medical training, the participants were asked whether they thought the inclusion of religion/spirituality themes in medical training was important. They could also choose from four responses: not, a little, reasonably and very important. The response to the question was categorised as ‘yes’ if the responses were very + reasonably important and ‘no’ if the responses were a little + not important.

To identify the barriers encountered by the participants in addressing religious/spiritual issues with their patients, they were prompted to respond to a multiple choice question with the following alternatives: (a) none, (b) fear of exceeding the role of a doctor, (c) lack of training, (d) lack of time, (e) not being comfortable with the issue, (f) the religious/spiritual aspect is not relevant for the patient, (g) fear of offending the patient, (h) fear that peers may not approve, (i) it is not the doctor's job, and (j) do not know why.

Statistical analysis

Evaluated outcomes

The analysis of data was done with Stata 12.1 software. For the continuous variables, the data were expressed as median (s.d.). Models of logistic regression were used to estimate the association between the psychiatrists’ general characteristics and having or not having a religious affiliation and their approach to religion/spirituality in clinical practice. All the patterns were adjusted by age, gender, and marital status and are presented as odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval.

Ethical issues

The current project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo Medical School. In addition to a detailed explanation of the study objectives, the participants received information regarding the confidential and voluntary nature of their participation in the research. Before completing the questionnaire, the participants had to agree and confirm electronically their free and informed decision to participate in the survey.

Results

In total 3120 emails were sent, of which 1779 were acknowledged and 1341 bounced back because of a variety of reasons (outdated email addresses, rejection by IPs and other technical reasons, such as full inboxes and identification as spam). From those 1779 email addresses, 492 completed the questionnaire (28%). Of these 492 questionnaires received back, eight were excluded (five senders did not match the list of emails sent, one for having been returned twice and another two because the questionnaire was not fully completed). The final number of completed questionnaires was 484.

Sociodemographic, professional and religious characteristics of Brazilian psychiatrists

A total of 484 psychiatrists completed the questionnaire, with an average age of 48.9 years (s.d.=11.8), of which 326 (67.4%) declared a religious affiliation and 345 (71.4%) said that they believed in God. Of the 158 without a religious affiliation, 45 (28.5%) said they believed in God (see Table 1).

Table 1 Brazilian psychiatrists’ religious/spiritual characteristics and their attitudes and self-reported behaviours regarding religion/spirituality in clinical practice (n=484)

| Religious/spiritual characteristics: n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Religious affiliation | |

| Catholic | 151 (31.2) |

| Spiritist | 87 (18.0) |

| Protestant or evangelical | 36 (7.4) |

| Other religion | 52 (10.8) |

| None | 158 (32.6) |

| Do you believe in God or a superior power? | |

| No | 92 (19.1) |

| Yes | 345 (71.4) |

| Undecided | 46 (9.5) |

| mv | 1 |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person? | |

| Very spiritual | 148 (30.6) |

| Moderately spiritual | 184 (38.1) |

| Slightly spiritual | 80 (16.6) |

| Not spiritual at all | 71 (14.7) |

| mv | 1 |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person? | |

| Very religious | 66 (13.7) |

| Moderately religious | 143 (29.6) |

| Slightly religious | 126 (26.1) |

| Not religious at all | 148 (30.6) |

| mv | 1 |

| Attitudes and behaviours regarding religion/spirituality in clinical practice: n (%) | |

| Do you consider it important to integrate patients’ religion/spirituality in clinical practice? | |

| Very important | 188 (38.9) |

| Reasonably important | 183 (37.9) |

| A little important | 68 (14.1) |

| Not important | 44 (9.1) |

| mv | 1 |

| Do you consider it important that the issues of religion/spirituality are included in medical training? | |

| Very important | 203 (42.4) |

| Reasonably important | 137 (28.7) |

| A little important | 73 (15.3) |

| Not important | 65 (13.6) |

| mv | 6 |

| How often do you enquire about patients’ religious/spiritual issues? | |

| Frequently | 220 (45.5) |

| Occasionally | 168 (34.8) |

| Rarely | 67 (13.9) |

| Never | 28 (5.8) |

| mv | 1 |

mv, missing values.

The majority (70.9%) were married or in a stable relationship, both in the group who had a religious affiliation (70.3%) and in the group who did not have a religious affiliation (70.1%). Most (89.7%) were adult psychiatrists, also evenly distributed in those who had and those who did not have a religious affiliation. Only those working in forensic psychiatry were more likely to have a religious affiliation (OR=1.86, 95% CI 1.02–3.39) (Table 2).

Table 2 Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of Brazilian psychiatrists and their distribution according to being with or without a religious affiliation

| Sociodemographic and professional characteristics | Religious affiliation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=484 (%) | Without n=158 (%) | With n=326 (%) | Adj. OR a (95% CI) | |

| Age in years | ||||

| 25–39 | 143 (29.5) | 50 (31.7) | 93 (28.5) | 1.00 |

| 40–59 | 236 (48.8) | 76 (48.1) | 160 (49.1) | 1.10 (0.71–1.73) |

| 60+ | 105 (21.7) | 32 (20.2) | 73 (22.4) | 1.36 (0.78–2.36) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 284 (58.7) | 105 (66.5) | 179 (54.9) | 1.00 |

| Female | 200 (41.3) | 53 (33.5) | 147 (45.1) | 1.65 (1.09–2.50)* |

| Marital status | ||||

| Without partner | 139 (29.1) | 43 (27.9) | 96 (29.7) | 1.00 |

| With partner | 338 (70.9) | 111 (70.1) | 227 (70.3) | 0.97 (0.63–1.51) |

| Subspeciality in psychiatry b | ||||

| Adult | 434 (89.7) | 139 (88.0) | 295 (90.5) | 1.46 (0.78–2.76) c |

| Child | 101 (20.9) | 33 (20.9) | 68 (20.9) | 0.95 (0.58–1.53) c |

| Old age | 107 (22.1) | 36 (22.8) | 71 (21.8) | 0.99 (0.62–1.58) c |

| Forensic | 72 (14.9) | 18 (11.4) | 54 (16.6) | 1.86 (1.02–3.39)* |

| Time (in years) as a psychiatrist | ||||

| 0–10 | 122 (25.6) | 35 (22.6) | 87 (27.0) | 1.00 |

| 11–20 | 123 (25.8) | 42 (27.1) | 81 (25.2) | 0.52 (0.27–0.97)* |

| 20+ | 232 (48.6) | 78 (50.3) | 154 (47.8) | 0.39 (0.18–0.83)* |

a Adjusted for age, gender and marital status.

b Multiple choice question: Figures for each category relate to total sample.

c Answers categories are ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and reference category is ‘no’.

* P<0.05.

On average, the participating psychiatrists had worked 21.3 (s.d.=11.7) years in clinical work. Those who had worked longer were less likely to have a religious affiliation (OR=0.39, 95% CI 0.18–0.83) (Table 2).

Of all the psychiatrists who responded, 76.8% considered it very or reasonably important to integrate patients’ religion/spirituality into clinical practice, and 71.1% considered it very or reasonably important to include religion/spirituality in medical training. In both cases, these participants were four times more likely (OR=4.33, 95% CI 2.75–6.81 and OR=4.14, 95% CI 2.69–6.36) to have a religious affiliation than those who considered it a little or not important to integrate religiosity in clinical practice or include it in medical training (Table 3).

Table 3 Attitudes regarding religion/spirituality in clinical practice of Brazilian psychiatrists (statistical analysis of the respondents from a total number of 484 participants)

| Attitudes regarding religion/spirituality in clinical practice | Religious affiliation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n= 484 (%) | Without n=158 (%) | With n=326 (%) | Adj. OR a (95% CI) | |

| Do you consider it important to integrate patient's religion/spirituality in clinical practice? | 371 (76.8) b | 91 (57.6) | 280 (86.1) | 4.33 (2.75–6.81)* |

| Barriers to address religion/spirituality with patient: c | ||||

| None | 195 (40.3) | 81 (51.3) | 114 (35.0) | 0.47 (0.32–0.70)* d |

| Fear of exceeding the role of the doctor | 146 (30.2) | 27 (17.1) | 119 (36.5) | 2.82 (1.75–4.54)* d |

| Lack of training | 108 (22.3) | 25 (15.8) | 83 (25.5) | 1.91 (1.15–3.17)* d |

| Lack of time | 79 (16.3) | 21 (13.3) | 58 (17.8) | 1.46 (0.84–2.53) d |

| Do you consider it important that the issues of religion/spirituality are included in medical training? | 340 (71.1) b | 80 (51.3) | 260 (80.7) | 4.14 (2.69–6.36)* d |

a Adjusted for age, gender and marital status.

b Includes responses ‘very important’ and ‘reasonably important’.

c Multiple choice question: Figures for each category relate to total sample.

d Answers categories are ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and reference category is ‘no’.

* P<0.05.

Regarding the barriers to addressing the patients’ religious/spiritual aspects in clinical practice, the most cited difficulties were the fear of exceeding the role of the doctor (30.2%), lack of training (22.3%) and lack of time (16.3%) (Table 3). The next most reported difficulties were not being comfortable with the issue (8.7%), it is not the doctor's job (7.6%), the religious/spiritual aspects are not relevant for the patient (7.0%), fear of offending the patient (6.4%), fear that peers may not approve (5.4%) and do not know why (2.9%). We also found that 40.3% of the total sample reported not having any barriers.

Those psychiatrists who reported having no barriers were less likely to have a religious affiliation (OR=0.47, 95% CI 0.32–0.70), whereas those participants who reported some barriers were more likely to have a religious affiliation (OR=2.82, 95% CI 1.75–4.54) (Table 3).

Religious/spiritual characteristics, attitudes and behaviours of psychiatrists and their religion/spirituality approach in clinical practice

Almost half (45.5%) of the psychiatrists surveyed said they frequently enquired about their patients’ religious/spiritual issues (Table 1). The participants’ sociodemographic background, the number of years of experience and psychiatric sub-specialisation were not associated with enquiring about the patients’ religion/spirituality.

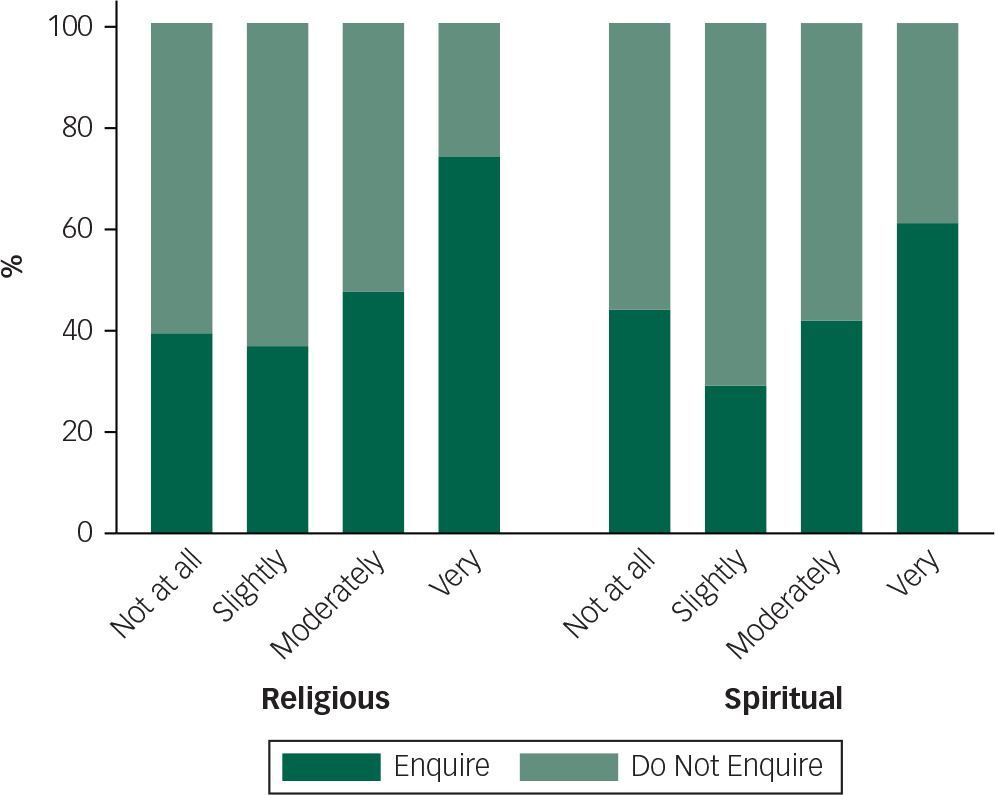

Only 43.3% of the respondents considered themselves to be very or moderately religious, whereas 68.7% considered themselves to be very or moderately spiritual, when answering the questions that distinguished religion and spirituality. An even smaller number, 13.7% of the psychiatrists, considered themselves to be very religious, and the great majority of these (74.2%) were almost five times more likely (OR=4.58, 95% CI 2.39–8.80) to ask their patients about their religious/spiritual issues than those who saw themselves as not religious at all. The psychiatrists who declared themselves to be slightly spiritual were less likely (OR=0.49, 95% CI 0.24–0.97) to enquire about patients’ religious/spiritual issues, when compared to psychiatrists who were not at all spiritual. On the contrary, those who were very spiritual (30.6%) tended to ask patients more often about their religion/spirituality (OR=1.87, 95% CI 1.05–3.35) (Tables 1, 4 and Fig. 1).

Table 4 Association between psychiatrist's characteristics and enquiring about patients’ religion/spirituality in clinical practice

| Enquire about patients’ religious/spiritual issues | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adj. OR a (95% CI) | |

| Religious/spiritual characteristics | ||

| To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person? | ||

| Not religious at all | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Slightly religious | 0.89 (0.55–1.46) | 0.89 (0.54–1.47) |

| Moderately religious | 1.39 (0.87–2.21) | 1.31 (0.81–2.10) |

| Very religious | 4.47 (2.35–8.51)* | 4.58 (2.39–8.80)* |

| To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person? | ||

| Not spiritual at all | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Slightly spiritual | 0.52 (0.25–1.02) | 0.49 (0.24–0.97)* |

| Moderately spiritual | 0.92 (0.53–1.59) | 0.87 (0.50–1.52) |

| Very spiritual | 2.00 (1.13–3.55)* | 1.87 (1.05–3.35)* |

| Religious affiliation | 1.52 (1.03–2.24)* | 1.45 (0.98–2.16) b |

| Attitudes regarding religion/spirituality in clinical practice | ||

| Do you consider it important to integrate patients’ religion/spirituality in clinical practice? | 2.20 (1.40–3.44)* c | 2.17 (1.38–3.43)* b |

| Do you consider it important that the issues of religion/spirituality are included in medical training? | 1.86 (1.24–2.81)* c | 1.91 (1.26–2.90)* b |

| Barriers to address religion/spirituality with patient: d | ||

| None | 3.24 (2.22–4.73)* | 3.25 (2.21–4.77)* b |

| Fear of exceeding the role of the doctor | 0.45 (0.30–0.68)* | 0.45 (0.30–0.67)* b |

| Lack of training | 0.94 (0.61–1.45) | 0.96 (0.62–1.49) b |

| Lack of time | 0.78 (0.48–1.28) | 0.81 (0.49–1.33) b |

a Adjusted for age, gender and marital status.

b Answers categories are ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and reference category is ‘no’

c Includes the responses ‘very important’ and ‘reasonably important’.

d Multiple choice question: Figures for each category relate to total sample.

* P<0.05.

Fig. 1 The figure represents how much psychiatrists enquire about religion/spirituality in their clinical practice, according to how much the psychiatrists consider themselves religious and spiritual.

The psychiatrists who considered it very or reasonably important to integrate religion/spirituality into clinical practice (OR=2.17, 95% CI 1.38–3.43) and medical training (OR=1.91, 95% IC 1.26–2.90), as well as those who reported not having any barriers to address religion/spirituality in clinical practice (OR=3.25, 95% CI 2.21–4.77), were more likely to enquire about their patients’ religious/spiritual issues, whereas those who reported that they feared exceeding the doctor's role were less likely (OR=0.45, 95% CI 0.30–0.67) to enquire about their patients’ religious/spiritual issues (Table 4).

Discussion

The results demonstrated that the great majority of Brazilian psychiatrists who replied to the survey considered it important to integrate religion/spirituality into clinical practice and into medical training. Half of them declared they frequently asked their patients about their religious and spiritual beliefs. The results also showed that there was no association between having a religious affiliation and enquiring about religion/spirituality in the clinical practice. However, psychiatrists who considered themselves to be very religious and/or spiritual were the most likely to enquire into their patients’ religion/spirituality in clinical practice.

Regarding religious and spiritual characteristics, 67.4% of Brazilian psychiatrists who responded to our survey had a religious affiliation, in comparison with 92% of the Brazilian population. 16 They also tended to have less religious affiliation when compared with psychiatrists in the United States (82%),Reference Curlin, Odell, Lawrence, Chin, Lantos and Meador 17 Germany (70.7%)Reference Lee and Baumann 11 and South Africa (84%).Reference Welgemoed and Staden 12

However, Brazilian psychiatrists showed a greater percentage of belief in God (71.4%), when compared with American (65%),Reference Curlin, Odell, Lawrence, Chin, Lantos and Meador 17 German (56%),Reference Lee and Baumann 11 Canadian (54%)Reference Baetz, Griffin, Bowen and Marcoux 10 and British (23%) psychiatrists.Reference Neeleman and King 9 In addition, as in the studies of CanadianReference Baetz, Griffin, Bowen and Marcoux 10 and American psychiatrists,Reference Curlin, Odell, Lawrence, Chin, Lantos and Meador 17 more participants in this study considered themselves to be spiritual than religious.

Perhaps there is a tendency for the surveyed psychiatrists to have a spiritual involvement that goes beyond social conventions, that is, it is possible that the beliefs of Brazilian psychiatrists tend to be more individualistic, independent or different from those connected with formal or institutional religions. Perhaps, since they belong to a society characterised by religious syncretism, it may be more difficult for them to relate to a specific religion, but they still reflect the high degree of religiosity of the Brazilian population. These levels are even more relevant when compared with the UK figures, in which a quarter of the population 18 and 73% of psychiatrists have no religion.Reference Neeleman and King 9

Although the majority of the Brazilian population is Catholic, it has been characterised by an increasing diversity of religious groups since the early 20th century. The Brazilian census shows an increase in Evangelical religions and Spiritism (a religious and philosophical movement initiated in the second half of the 19th century), at the expense of Catholicism. However, the Catholic religion is still by far the largest in Brazil, and in our sample, Catholics comprise, as expected, the largest group, with Spiritists second, followed by Evangelicals. Spiritism has been popular amongst liberal professionals in Brazil but the Evangelicals are usually more prevalent in the middle-low and low socioeconomic levels. 16

The results also indicated that women were more likely to declare a religious affiliation. There are studies in other countries which present similar observations. For example, a Canadian studyReference Baetz, Griffin, Bowen and Marcoux 10 reported that female psychiatrists had higher rates of religious beliefs, religious practices and intrinsic religiosity than male colleagues. Neeleman & KingReference Neeleman and King 9 in the UK also found that the rate of female psychiatrists who believed in God was higher. Despite the good empirical evidence to support these observations, there is a lack of empirical studies and a satisfactory theoretical basis to explain these differences.Reference Francis 19

Among the medical specialties, psychiatry has been described as the least religious.Reference Curlin, Lawrence, Odell, Chin, Lantos and Koenig 13 , Reference Robinson, Cheng, Hansen and Gray 20 An interesting observation in this survey was that those working in forensic psychiatry were the most likely to declare a religious affiliation. To our knowledge, there are no studies addressing the relationship between subspecialties in psychiatry and religion/spirituality, making it an interesting subject for further investigation.

We also found that not only the subspecialty but also the number of years working in psychiatry could be associated with having or not having a religious affiliation, with those with more time in the profession less likely to have any religious affiliation. A similar observation is presented in a Canadian study about psychiatristsReference Baetz, Griffin, Bowen and Marcoux 10 which shows that as the years of professional practice increased, the importance attributed by psychiatrist to religion/spirituality in psychiatry decreased.

Of course, the field of psychiatry has changed considerably over the past decades, as has the relationship between psychiatry and religion, so the comparison of different studies should be made with caution, since these results may reflect a generational phenomenon, rather than be a function of time in the specialty.

For instance, it is worth remembering that psychiatry was strongly influenced by Freudian views that referred to religious ideas as being illusions, a product of neurosis and close to being ‘psychiatric delusions’.Reference Freud and Strachey 21 This meant that some theoretical ideas understood religious expression to be pathological and for a long time influenced professionals in the area.Reference Neeleman and Persaud 22

In addition, some authors have emphasised the importance of discussing religion/spirituality in the therapeutic context and distinguished between their positive and negative aspects.Reference Koenig 23 , Reference Moreira-Almeida, Koenig and Lucchetti 24 They show that the ability to differentiate the pathological from the non-pathological contents of some manifestations of religiosity/spirituality sometimes depends on specific training.Reference Moreira-Almeida and Cardena 25 Psychiatrists need not only to be able to make this distinction but also to be able to identify symptoms that are a result of the psychopathology rather than precede it or deal with even more complex cases which can present a combination of both manifestations.Reference Pirutinsky, Rosmarin, Pargament and Midlarsky 26

As in other studies,Reference Neeleman and King 9 , Reference Curlin, Lawrence, Odell, Chin, Lantos and Koenig 13 , Reference Lawrence, Head, Christodoulou, Andonovska, Karamat and Duggal 14 where there is a wide agreement among psychiatrists about the need for the integration of religion/spirituality in clinical treatment, the vast majority of psychiatrists in this study considered it to be very or reasonably important to integrate their patients’ religion/spirituality into their practice. Unsurprisingly, believing in the importance of the integration of religion/spirituality into clinical practice and medical training were also associated with greater rates of religious affiliation.

Some studies show that although psychiatrists consider it important to integrate religion/spirituality in the therapeutic context, in practice this does not often happen,Reference Neeleman and King 9 , Reference Baetz, Griffin, Bowen and Marcoux 10 unless the patients themselves took the initiative.Reference Durà-Vilà, Hagger, Dein and Gerard 27 In our study, 45.5% of the participants stated they often discussed religion/spirituality with their patients, a much lower figure than that reported in the study by Curlin et al, Reference Curlin, Lawrence, Odell, Chin, Lantos and Koenig 13 where a higher proportion (87%) of American psychiatrists reported always asking about their patients’ religion/spirituality.

Although a high proportion of psychiatrists declared that they do not have any barriers in addressing their patients’ religion/spirituality, the most commonly mentioned barriers were similar to those of previous studies:Reference Curlin, Lawrence, Odell, Chin, Lantos and Koenig 13 , Reference Durà-Vilà, Hagger, Dein and Gerard 27 the fear of exceeding the role of a doctor, lack of training and lack of time.

The psychiatrists who declared that they did not have any barriers in addressing religion/spirituality in clinical practice were the most likely to enquire about these issues with their patients and less tending to have religious affiliation, whereas those who indicated having barriers such as the fear of exceeding the doctor's role and lack of training were the most likely to declare a religious affiliation, and, unsurprisingly, less likely to inquire about patients’ religion/spirituality.

The Brazilian psychiatrists, as in studies with South AfricanReference Welgemoed and Staden 12 and British psychiatrists,Reference Neeleman and King 9 showed that having a religious affiliation itself was not associated with psychiatrists asking about their patients’ religion/spirituality. However, considering oneself very spiritual, and especially very religious, is associated with this. These findings are similar to an American studyReference Curlin, Chin, Sellergren, Roach and Lantos 28 performed with general practitioners, which showed the more they identified themselves as spiritual and religious, the more likely they were to enquire about their patients’ religious/spiritual issues. Although the psychiatrists in our study who declared themselves to be very religious were relatively few (17%), they were almost five times more likely to enquire into their patients’ religious and spiritual issues, when compared with those who declared themselves to be not religious at all.

Limitations

This study has some methodological limitations. Among them, perhaps the most important, is its cross-sectional nature, with information being collected through the self-reports of psychiatrists. In addition, a generalisation of the data has to be carried out carefully since the response rate could be considered as relatively low (28%), despite the overall sample size (n=484 from a total of 1779). However, the reply rate is in the expected range for research that uses electronic methods of data collection (email). Studies show that psychiatrists are often reluctant to participate in opinion pollsReference Cunningham, Quan, Hemmelgarn, Noseworthy, Beck and Dixon 29 and generally present a low return to surveys, including in Brazil.Reference Banzato, Pereira, Santos, Silva, Loureiro and Barros 30 Moreover, the response rates for surveys performed via the Internet are lower in relation to those conducted by face-to-face, mail or telephone methods.Reference Nulty 31 However, 28% of those contacted completed the survey, a participation percentage higher than in other studies using a similar methodology.Reference Nulty 31 , Reference Duarte, Osis, Faúndes and De Sousa 32 The rate of response for studies involving business people,Reference Harzing 33 psychiatristsReference Banzato, Pereira, Santos, Silva, Loureiro and Barros 30 and oncologistsReference Samano, Ribeiro, Camos, Lewin, Filho and Goldenstein 34 is not usually more than 20%. In a more recent example in Brazil of a survey through the Internet, involving 365 spiritist centres in the city of São Paulo,Reference Lucchetti, Lucchetti, Leão, Peres and Vallada 35 only 15% agreed to participate.

Another possible limitation of the sample is that it may have selected individuals who are more passionate about the issue both for and against, so that those who are more religious and those who are not religious may have felt more inclined to respond to the questionnaire. Curlin et al Reference Curlin, Chin, Sellergren, Roach and Lantos 28 suggested that non-religious doctors might have been more inclined to participate in the research.

Finally, a potential difficulty when interpreting the results concerns the definition of complex and multifaceted concepts such as spirituality and religiosity. In the present work, the terms religion and spirituality were not defined, allowing the respondents to apply their own definitions, and therefore, the survey results should be interpreted with caution. In addition, since there is no universal definition accepted by researchers, this lack of consensus also causes difficulty and requires caution when comparing the results between studies.

Final remarks

This is the first systematic Brazilian survey asking psychiatrists about religion/spirituality in their practice, and whether their own beliefs influence their clinical work. Two-thirds of the participants of this survey had a religious affiliation, and almost half enquired frequently about their patients’ religion/spirituality. Most of the participants are in favour of establishing training programmes to improve the skills of psychiatrists in respect of their approach towards patients’ religion/spirituality. Respondents also support the idea of creating a course related to religion/spirituality for undergraduate medical students. A larger survey involving a greater number of psychiatrist participants and using a more detailed questionnaire would be necessary to confirm and clarify the preliminary results of this study.

Furthermore, new studies to evaluate and understand the role of psychiatrists who include or do not include an assessment of their patients’ religion/spirituality into their clinical practice as well as into their treatment plans and prevention strategies will be needed. In summary, this is a new area of investigation that could contribute significantly to a better clinical outcome for psychiatric patients.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Associação Mantenedora João Evangelista, São Paulo, Brazil.

Acknowledgements

We thank Francisco Lotufo Neto and Alexander Moreira Almeida for their support and encouragement, Marcia Scazufca and Camila Martins for their statistical assistance, all the psychiatrists who took the time to complete the survey, and the Brazilian Association of Psychiatry.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.