The opera Die Gezeichneten (‘The Marked Ones’ or the ‘Stigmatised’) by the Austrian composer Franz Schreker (1878–1934) straddled the pre- and post-First World War periods. Schreker wrote the opera's text himself in 1911, after his Viennese contemporary Alexander Zemlinsky requested a libretto about ‘the tragedy of the ugly man’.Footnote 1 He never parted with the text, setting most of it to music before the arrival of the war and finishing the score in June 1915. Wartime conditions pushed back the opera's premiere: it was initially planned to take place in Munich in 1915 but finally materialised in Frankfurt on 25 April 1918.Footnote 2 Die Gezeichneten's allure comes from its resistance to being reduced to only one thing.Footnote 3 While much scholarship on the opera has focused on the pre-war context of its composition,Footnote 4 this article seeks to locate Die Gezeichneten around the time of its premiere towards the end of the First World War. The opera's first performances coincided with the end of the war, and its early reception with the birth of the Weimar Republic as well as the short-lived Republic of German-Austria.Footnote 5 The economic, social and psychological consequences of Austria and Germany's defeat informed Die Gezeichneten's reception during those years;Footnote 6 indeed, César Saerchinger wrote in 1919 that

In the last year of the war, in the midst of that terrible spring offensive which tore Germany down into the abyss, Schreker's great new work, ‘Die Gezeichneten’, was produced. The way in which the people received it seemed to say that here, at last, was what they had been groping for.Footnote 7

While 1918 presents no complete break from the world before, I contend that Die Gezeichneten and its immediate reception charted a key transition in Austro-German masculinity. Specifically, the opera's early performances marked a move away from the period's normative models of bourgeois masculinity (and their corresponding ideas about appearance, health and nationhood) and towards an alternative masculinity marked by degeneracy.Footnote 8

In order to understand this shifting conception of masculinity, I focus on the opera's use of masks and on the language of degeneracy that critics used to describe its vision of a subversive, anti-bourgeois masculinity. The opera's masks – a recurring but seldom discussed feature of Die Gezeichneten – emerged out of a fin-de-siècle Austro-German fascination with appearance and concealment;Footnote 9 their arrival onstage challenged the First World War-era pressure on disfigured veterans to uphold a normative standard of masculine beauty by donning masks. Focusing on literal masks and figurative forms of masking (such as a disconnection between appearance and voice), I argue that Schreker's opera called attention to wartime anxieties about manhood. The anxieties resulted in a hardening of attitudes towards the masculine gender, which influenced contemporary music criticism too. In the final part of this article, then, I re-examine Die Gezeichneten's early reception by analysing reviews of its German and Austrian premieres. The highly sensationalist reviews relied on a language of degeneracy, a quality associated with formlessness, excess and artifice, which later became a primary linguistic register of Nazi Germany's fascist regime; Schreker was classified as a ‘degenerate’ composer. I will argue here that the early reviews captured a critical moment in this language's history before it was subsumed under Nazi ideology. Ultimately, both the opera and the early reviews reflected an uneasiness about the confines of manhood, and they confronted these limitations by deliberately highlighting the attractions of degeneracy.

Bourgeois masculinity in and after the First World War

Physical appearance played an important role in European perceptions of masculinity, even – and perhaps especially – in the middle of a bloody war. The face, in particular, became a site of intense socio-political scrutiny about normative masculinity in the First World War. Since the face was the part of the body least protected against the increased power of artillery in the early twentieth century, facial wounds were not only common but also frequently severe.Footnote 10 Moreover, new medical developments enabled the survival of badly injured – including badly disfigured – soldiers who previously would have died. War-maimed faces exposed the vulnerability of the human body, while also representing a frightful encroachment of the war on the home front. As Ana Carden-Coyne writes after Suzannah Biernoff, the ‘extreme suffering and the violation to the face, the touchstone of humanity, undercut fantasies about heroic warfare and the capacity of military masculinity to withstand modern technological warfare’.Footnote 11 While reconstructive surgery hid the damage of warfare to some extent, there were nevertheless facial injuries so awful that men felt it necessary to conceal their broken features with masks.Footnote 12 Previously a playful device for concealment and for transgressing social norms in the fin de siècle, masks acquired a new purpose – and a new set of meanings – as a means to deny the trauma of war. Rather than facilitating re-entry into civilian life, such masks (even carefully crafted artisanal masks) caused facially disfigured soldiers to become the subject of fervent socio-political debate. People not only expressed physical repulsion towards men who wore masks but also – often irrationally – questioned these men's ability to work. Masks therefore obscured the injuries of war but cast doubt on the men's socioeconomic values and even moral standards, raising issues that bound good looks with a man's worth in the evolution of modern masculinity.

Indeed, looking ‘repulsive’ was conceptualised as analogous to ‘being dependent’.Footnote 13 Even though damaged faces do not hinder physical labour in the same way as damaged limbs, the soldiers’ war-torn faces became an obstacle to both the Allies’ and the Central Powers’ post-war economic recovery, because the men simply did not fit the modern image of manhood.Footnote 14 As George L. Mosse argues, ‘not only comportment but looks mattered’ in the modern conception of the masculine ideal.Footnote 15 To look good was not only to look a part but to be a part of the new bourgeois ideology of masculinity that privileged industriousness as well as the social and material achievements that were assumed to follow.Footnote 16 Even before the war ended, the militaries of both the Central and the Allied Powers dismissed ‘men who were badly disfigured for the reason that the psychologic effect on other soldiers interfered with discipline’.Footnote 17 The post-First World War debate on masculinity and appearance continued in this same vein, connecting a facial injury's destabilising impact to the loss of financial independence and, consequently, of normative manhood.Footnote 18 In this context, where male beauty was closely tied to masculine identity, society and nationhood, the men who returned from the war with mutilated faces lost more than their previously intact physiognomy.Footnote 19

This correlation between outward appearance and inner nature came to encompass the private sphere, too. An unsightly face in the bourgeois conception of masculinity indicated not only a compromised ability to work but also an inability to control one's desires.Footnote 20 It was in this moralistic pursuit of a highly regulated bourgeois masculinity that the Central Powers’ medical professionals legitimised their encroachment on ordinary men's sex lives, by citing the need to ensure a steady supply of military power during the First World War.Footnote 21 Sex – and more precisely, state-sanctioned bourgeois sex within the institution of heterosexual marriage – served as a technology for circumscribing permissible forms of masculine behaviour and therefore a German ‘remasculinisation’.Footnote 22 The wartime image of a soldier was in essence asexual.Footnote 23 After all, his love for his country ought to transcend his own bodily desire when he was in battle away from his wife, and his innate mental strength should prevent him from the supposedly perverse sexual behaviours that were emerging from the psychological traumas of the war. Indeed, the Central Powers’ authorities worked themselves into a frenzy over the licentiousness of the military's ‘sexual deviants’. Just as Frankfurt Opera was preparing to premiere Schreker's Die Gezeichneten, then, news was spreading on the home front about soldiers’ sexual activities in the horrifyingly bloody trenches.Footnote 24

Offering no corrective to perceived gender anomalies, Die Gezeichneten resisted – in parallel with diverging realms of wartime society – bourgeois standards of masculinity. For example, the Männerbund (male society) – a term that describes all-male military or military-adjacent camaraderie with homoerotic overtones in the post-1871 but pre-Second World War context – allowed men to bypass the social conventions of bourgeois masculinity while still appearing faithful to middle-class principles of honour and purity.Footnote 25 In the sphere of media production, the Herrenabende (gentlemen's evenings) organised by movie companies such as Saturn-Film before the war similarly contributed to subverting hardening ideals of the appropriate male expression of desire.Footnote 26 Reportedly producing films more tantalising than those of their French competitors, the Austrian Saturn-Film showed not only pornography but also films about bodily deformities and surgical operations.Footnote 27 Although Austria outlawed the ‘gentlemen's evenings’ before the war as a result of unwanted international attention, the organisers of these events simply operated out of the sight of state authorities until they re-established themselves in the field cinemas of the First World War.Footnote 28 Saturn-Film's interests in the erotic as well as the grotesque contributed to contemporary bourgeois anxieties about what it meant to be a man – about male appearance, sexual desire and the moral injunctions ascribed to both the exterior and the interior of maleness. By refusing to connect bourgeois respectability with national aspirations, Saturn-Film demonstrated support for factions of marginalised society which were ostensibly sexually excessive and strange-looking.

What transpires in Die Gezeichneten that puts it in dialogue with institutions such as Saturn-Film? Set in sixteenth-century Genoa, the opera features a crippled, hunchbacked nobleman, Alviano Salvago. His ugliness contrasts sharply with the beauty of the count, Vitelozzo Tamare, who forms a sort of Männerbund with a group of sex-driven aristocrats that excludes Alviano. Instead of simply finding homosocial solace, they abduct and rape Genoa's daughters in a secret grotto underneath Alviano's paradise island, Elysium. Elysium's wonder is an externalisation of Alviano's hitherto unfulfilled erotic desire. Yet in response to learning how his peers have corrupted his idea, Alviano gifts the island to the people of Genoa. In the process, he encounters Carlotta Nardi, the Podestà's daughter and a talented painter who makes Alviano believe in the possibility of love despite his appearance. She wishes to – and does – paint Alviano. Yet as soon as she finishes her painting, she appears to lose interest in the ugly protagonist and runs away from their betrothment. The story culminates in the uncovering, in front of all the Genoese, not only of the criminal sexual activities hidden beneath Elysium but also of Tamare's devouring of Carlotta. The heartbroken Alviano stabs his romantic rival to death, just as the dying Carlotta wakes and calls out to Tamare. Scholars such as Michael Ewans have focused on the opera's triangular romance, declaring the opera's key themes to be ‘love and loss’.Footnote 29 Here I wish to interrogate what lies beyond this amorous entanglement: namely, the opera's treatment of masculine gender stereotypes and what they say about early twentieth-century politics of degeneracy.

The opera presents to its contemporary audience figures onstage that resist narratives of normative manhood. Adrian Daub writes that the presence of an ugly character in early twentieth-century opera represents a revolt against the totality – ‘the overweening integration and the overweening Germanness’ – of Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk.Footnote 30 Ugliness as ‘the only detail amiss in the lavish spectacle’ reveals a new, post-Wagnerian perspective that is more sympathetic to the fractured tale of Mime than to the heroic myth of Siegfried. Die Gezeichneten is among the works that Daub studies, and it is emphatically enormous even by Schreker's standards: it comprises 30 singing roles (although some parts may be doubled), a chorus, mute actors, dancers and a 120-person orchestra.Footnote 31 However, while I concur with Daub that the presence of a deformed protagonist challenges Wagnerian fantasies of wholeness and grandeur, I suggest that Die Gezeichneten's departure from such fantasies rests not solely on Alviano's appearance but also on music that sometimes falls short of a purported masculine ideal; indeed, the size of Schreker's orchestra is itself already an instrument of musical excess. I contend after David Klein that Alviano's voice is not always beautiful.Footnote 32 Rather, Alviano sometimes lapses into declamation. Moreover, despite his distinctive ugliness, Alviano is not alone in being confronted with the failure of his own voice. Through acts of concealment and disclosure, both Alviano and Tamare will struggle to negotiate expectations of an emotionally controlled modern manhood, rising above descriptions of them as opposing emblems of beauty and ugliness.

Alviano's masculine masks

Alviano is physically, socially and audibly different. Physically, he is as Daub describes – he stands as a ‘solitary’ figure and even an object of ‘derision or incomprehension’ among the opera's outwardly beautiful characters.Footnote 33 He is sexually frustrated, and somewhat lonesome even in his own lavish and staffed palace. As a direct reference to Wilde's ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’ and in an act of self-denial, Schreker's Alviano has ‘banished mirrors from his apartments’, as someone ‘who hates himself, who flees from himself’.Footnote 34 The libretto indicates as much early in the opera: for example, during Alviano's first meeting with the Podestà's family at his banquet, organised to initiate the gift of Elysium (Act I scene 4). At this meeting, the Podestà marvels at the house before he introduces his wife and daughter to Alviano,Footnote 35 evidencing their unfamiliarity and Alviano's self-seclusion (notwithstanding that there are, of course, dynamics of class difference in play, with the elected representative of middle-class Genoese finding himself in the middle of an aristocratic palace). Crucially, too, while the rest of the noblemen appear to socialise regularly at Alviano's house, they are not necessarily there because of Alviano; indeed, Alviano only learns about the true horror of his fellow noblemen's sexual adventures at the beginning of the opera.Footnote 36 Alviano's aristocratic status and his grand palace allow him to be at the centre of Genoa's high-status social scenes. However, the opera's libretto repeatedly points to not only his sexual frustration but also his social alienation.

This alienation is musically audible. At first hearing, Alviano's music is unremarkable: in Daub's description, he can ‘sing just as beautifully as everyone else’, fulfilling what Sherry D. Lee calls ‘the fundamental operatic requirement of beautiful singing’.Footnote 37 In both the orchestra and the vocal part, his music nevertheless reveals more than meets the ear about his psychic interior. As the curtain opens on Act I scene 1, for instance, the restless (hastig, ‘hurried’) Alviano is in a heated discussion with his fellow noblemen about their appalling crimes of abduction and rape. Straight away, this character – who is, in Daub's terminology, a reiteration of Mime rather than Siegfried – is compromised by the almost sinister-sounding opening from the bassoons and horns (4 bars before rehearsal 1). Then the intertwining orchestral figures in steps, thirds and turns in close range, in the initial 21 bars alone, insinuate a character whose bewilderment drives him in circles. Alviano's voice, too, differentiates him from his fellow noblemen in this opening scene. While his first ‘somewhat melodious line’ (einigermaßen melodiöse Linie) only emerges after ten bars, the rest of the noblemen's more sustained phrases instantly and collectively create a sense of ‘endless melody’.Footnote 38 As Klein contends, the broken syntax of Alviano's first sentences reflects the character's fragmented psyche; his voice, which resists the safety of bel canto singing, indicates a deeper and more complex personhood.Footnote 39 The bel canto emerges when Alviano conceals aspects of himself that might render him a weak, unstable and nervous man. The unremarkableness of his bel canto hence masks his insecurity.

Masks feature concretely and figuratively in Die Gezeichneten. They allow for an exploration of the relationship between exteriority and interiority – between ‘surface appearance and inner nature’ – which was already fundamental to fin-de-siècle aesthetic culture, as Lee writes in her comparison of Schreker's opera with Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray.Footnote 40 For Alviano, while the uniform bel canto singing of his noblemen peers denotes a normative presentation of masculinity that is not wholly accessible to him, this ugly character's beautiful island of Elysium can similarly be read as a façade. He has envisioned and financed the construction of an externalised mask, the Elysium, through which he seeks self-worth and his own sense of beauty. I concur with Klein that all three of Die Gezeichneten's central characters grapple with the inconsistency of their singing voices, lapsing at times into declamation and even almost speech. Alviano nonetheless uniquely bears the burden of his ugliness. His onstage presence resonates with the contemporaneous necessity of concealing wartime injury. As such, more than a commentary on fin-de-siècle aesthetic culture,Footnote 41 Alviano's story represents a challenge to the social politics of a technocratic-militarist masculinity that persisted through the tail end of the First World War.

Tamare's masculine masks

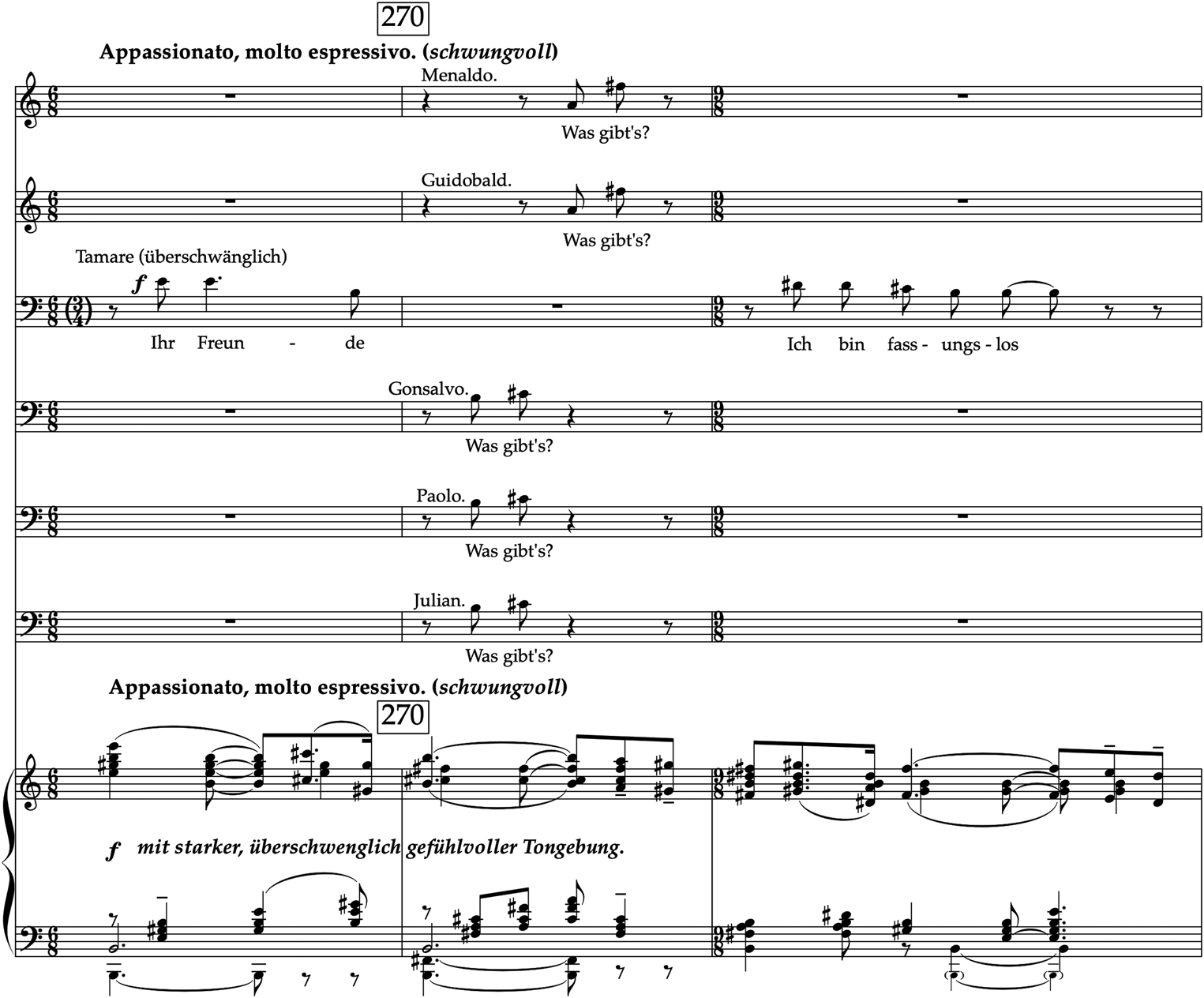

In contrast to Alviano's precarious beginning, Tamare starts by singing confidently, and yet he also takes on masks of his own. His singing destabilises the myth of Siegfried because his music is often so exaggerated that it becomes suspect.Footnote 42 Already, in the prelude, the first sounding of Tamare's leitmotif is marked ‘with brutal passion’ (Mit brutaler Leidenschaft) (rehearsal 10), and Lee observes that it modulates from D major to B flat major in its initial four bars, which ‘darkens the rest of the theme’.Footnote 43 Likewise, vocally, this handsome baritone's high-flown singing suggests an attempt to disguise his fears and insecurities about his masculinity with the mannerisms expected of heroic tenors, prompting listeners to ask what might lie behind his carefully stylised voice. He rushes onstage in Act I scene 3 to the sonorous welcome of his noblemen friends, who have just been startled and exasperated by Alviano's announcement about Elysium. Unapologetic about his late arrival, Tamare projects his singing voice against the entire orchestra. His voice is warm and exuberant with four separate expression markings at b. 269 that underscore the potency of his music: for the voice, ‘effusive’ (überschwänglich), and for the orchestra, Appassionato, molto espressivo, ‘spirited’ (schwungvoll) and ‘with strong, lavishly expressive intonation’ (mit starker, überschwenglich gefühlvoller Tongebung) (Example 1). This handsome character establishes himself straightaway in the richly coloured, exultant key of B (via E) with sustained arches of melodic phrases in the bright upper register of his voice (bb. 269–77). His overly forceful pursuit of beautiful singing has the effect of projecting – as Alviano's bel canto singing does – a normative masculine outlook.

Example 1. Act I scene 3, bb. 269–271. Franz Schreker Die Gezeichneten © Copyright 1916 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien / vocal score UE 5690

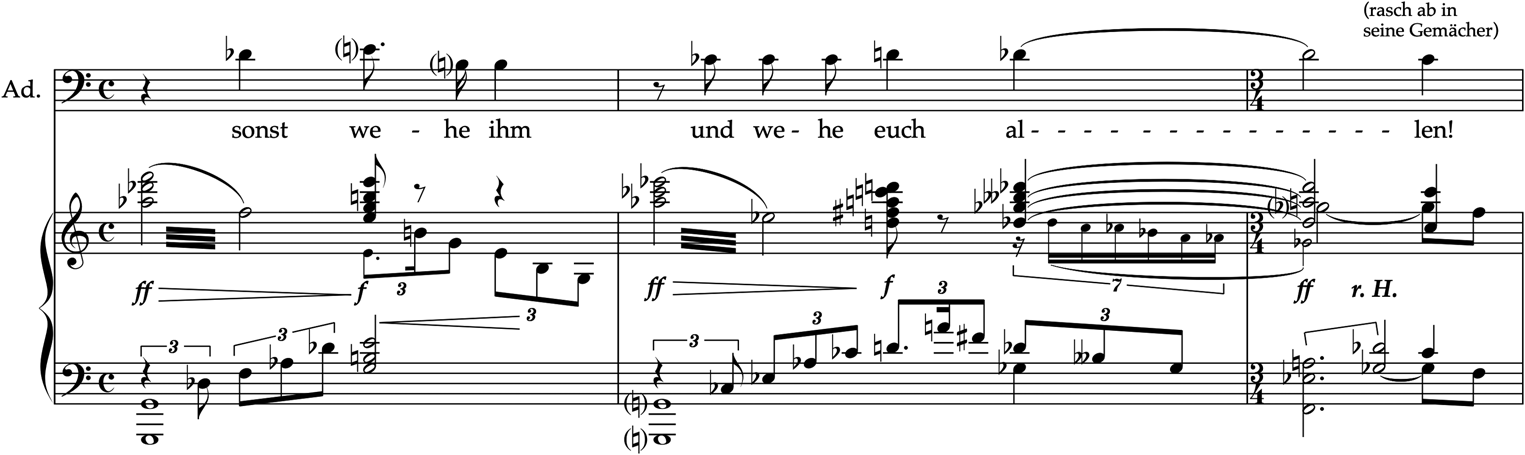

The dialogue with Duke Adorno, the opera's figure of paternal authority, in Act II scene 2 confirms that singing for Tamare functions to maintain a veneer of masculine self-control, and it operates in conjunction with rather than in opposition to non-singing. Two factors support this reading. First, Tamare declaims as Alviano does (as Klein observes),Footnote 44 and Tamare's short and declaimed opening phrases from this scene suggest an emotional terrain that overlaps with Alviano's at his entrance. Second, Tamare is only able to sing with relative ease while he idealises a past of blissful ignorance. His phrases elongate as he reminisces in a Siegfried-like fashion about a time when he knew no suffering. His arching ‘arioso, with momentum’ (arios, mit Schwung) flows above the orchestra's chordal accompaniment (b. 115ff.).Footnote 45 Yet Tamare only resembles Siegfried on the surface. His overdetermined singing takes over the remainder of the scene and exposes his inability to conform to the bourgeois ideal of emotional restraint.Footnote 46 He loses control as he continues. Acutely aware of his self-fashioning, he enunciates in the third person: ‘Count Andrae Vitelozzo Tamare offering her his heart and hand.’Footnote 47 (Example 2) With every note accented, his voice almost bursts with anger at the beginning of the descending A minor line, which is made dissonant by the voice's suggestion of G7 (bb. 183–86).Footnote 48 The violence of his voice culminates when he declares that he will forget Carlotta only when he has made her his ‘whore’,Footnote 49 reaching F4 (b. 288) in a full-blown desire for revenge. Tamare's strained voice disrupts the effortlessness required for the representation of an ideal, making his masculinity not wholesome but instead deviant. Between his overstated machismo and emotional breakdowns, Tamare's singing produces at best hollow bravado, and his declamatory disintegration confirms the rigidity of his vocal posturing.

Example 2. Act II scene 2, bb. 182–186. Franz Schreker Die Gezeichneten © Copyright 1916 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien / vocal score UE 5690

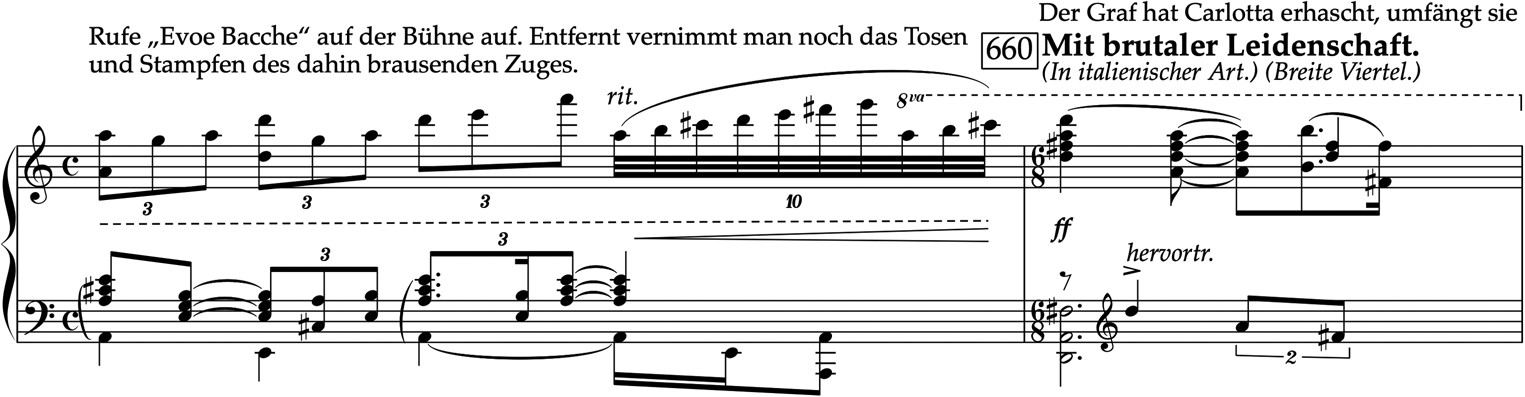

Most tellingly, Tamare puts on a literal mask, disguising his vulnerable self. Hidden behind a mask, he resumes his command of lyricism when he reappears in Act III scene 15. Tamare's theme has been rendered suspect from the beginning, but his music is overstated once again as he regains composure behind his mask. When his orchestral leitmotif is reintroduced in this scene, alongside expression markings including ‘with brutal passion’, the composer further specifies ‘in the Italian style’ (in italienischer Art) (b. 660), drawing on the traditional Italian mode of operatic performance and exploiting long-held stereotypes of Italian masculine bravado (Example 3). Schreker taps into German prejudice against Italian opera's ‘shallow music tailored to the latest fashion’ (as Gundula Kreuzer has summarised).Footnote 50 The superficiality of Tamare's Italianate sexual prowess appears at odds with German stoicism, and it merely follows Italian operatic clichés.Footnote 51 Since Tamare is wearing his mask when Carlotta surrenders to his embrace, she succumbs merely to the idea of a beautiful man and not Tamare. By disguising himself, he essentially admits not only that he needs Duke Adorno's help, but that he can only successfully navigate the world in the appearance of someone else. Tamare's multilayered disguises, void of substance, become another means through which Die Gezeichneten is critically reflective of the contemporary unease about gender and nation.

Example 3. Act III scene 15, bb. 659–660. Franz Schreker Die Gezeichneten © Copyright 1916 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien / vocal score UE 5690

Love interest and paternal authority

Some space must be given to two characters in the opera who closely relate to Alviano and Tamare and who obviously shape their masculinities. The first is Carlotta, the opera's female protagonist, and the second is the above-mentioned Duke Adorno. Carlotta stands between Alviano and Tamare as their mutual love interest and is at different times attracted to and repelled by them. Significantly, her relationships with them undermine rather than affirm heterosexual romance's promises of modern bourgeois masculinity and its moral integrity, because there is always at least one character who hides their true self in the romantic encounters. For example, in the opera's Atelier scene, in which Carlotta paints Alviano and makes him bare his inner self by talking him into a rapture, she conceals her own interior as she attributes her works and artistic desires to a female acquaintance (Alviano likewise resists Carlotta's gaze at first because he is haunted by ideas of normative beauty).Footnote 52 It is only at the very end of the scene, when she faints and in effect forecloses any real possibility of consummating with Alviano, that she unwittingly uncovers a painting of a hand – one she has ascribed to the friend – to reveal her true self.Footnote 53 Likewise, when she runs away with Tamare after having previously rejected him so cruelly that his voice crumples,Footnote 54 she does so with Tamare in disguise, his identity hidden, as discussed above. Despite her position as a woman artist (remarkable both in terms of Schreker's opera and what was permissible historically at the time), she ultimately becomes a foil for the opera's central male characters.Footnote 55 As Lee observes, Carlotta becomes at the end ‘unmistakably a Weiningerian woman, whose complete surrender to sexuality overrides not only rationality and morality but lofty intellectual or creative ideals’.Footnote 56 Her unmasked self is a tool for the opera's examination of manhood.Footnote 57

The opera puts further pressure on normative masculinity via the figure of Adorno. As the opera's chief embodiment of a technocratic-militarist masculinity, he reigns over Genoa by virtue of his title, wealth and private army. He uses his power to enable Tamare's heterosexual romance with Carlotta but to thwart Alviano's – and, in the process, to defend himself.Footnote 58 Adorno offers to pursue Carlotta on Tamare's behalf when Tamare reveals in Act II scene 2 the fragility of his masculinity, having failed to win Carlotta's attention. However, Adorno's defence of Tamare's amorous pursuit is quickly rendered suspect because Adorno can only fulfil his promise dishonestly by covering up Tamare's crimes and blaming Alviano for them. While Adorno appears as a disciplinarian whose restrained high-bass voice is kept within the octave of C3–C4, there are glimpses into the tenuousness of this supposedly stoic militarist masculine subject. For example, towards the end of Act II scene 2, as Adorno becomes increasingly agitated by Tamare's descriptions of the crimes that happen underneath Elysium, he progressively loses control of his voice, reaching C4, D4 and even E4 (b. 414ff.; bb. 442–444 especially) (Example 4). With Alviano, since the ugly protagonist's gift of Elysium must be ratified by him and because Alviano is to wed Carlotta at the celebration of his gift, Adorno is in a position to – and does – frustrate Alviano's sexuality. By refusing to endorse Alviano's gift, Adorno prevents Alviano's chance at marriage and at achieving a marker of normative manhood, thereby prolonging the psychological torment of this character.

Example 4. Act II scene 2, bb. 442–444. Franz Schreker Die Gezeichneten © Copyright 1916 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien / vocal score UE 5690

Act III: The populace in a frenzy

The arrival of the Genoese citizens on the island prompts Act III's rapid succession of 20 short scenes as Die Gezeichneten progresses towards its climax. Eventually donning their own masks, the Genoese will play an important role in challenging the parameters of masculinity in and for the opera. They are a heterogenous group in their age, gender and aesthetic values; they are, in Peter Franklin's description, ‘divide[d] variously into potential aesthetes, conservative art censors and the more passively manipulated’.Footnote 59 As such, the Genoese fulfil two functions. First, they participate in – and push back against – the cultural codification of femininity and degeneracy by their sheer presence, which represents part of the opera's excess and in turn threatens the masculine ideal of restraint; indeed, as Franklin contends, spectacular scenes such as the final ones of Die Gezeichneten are indicative of ‘Schreker's extraordinary grasp of the implications of feminized theatrical and musical spectacle’.Footnote 60 Second, they test the boundaries of the hegemonic masculinity that circumscribes the two central male characters by observing and commenting on the events of the Act. Given their position as spectators, the Genoese citizens effectively experience the events onstage for the audience in the theatre. Die Gezeichneten's Act III therefore offers a metadiscursive turn: the Genoese become the critics within the opera whose voices and opinions allow the composer to answer his critics outside of it. Die Gezeichneten opens up possibilities for subverting hegemonic masculinity because it actively plays a part in ‘discourse about art and degeneracy in the spirit of the times in which it was written’.Footnote 61

Building on Franklin's reading of the opera's treatment of the pre-fascist discourse of degeneracy, I argue here that the Genoese citizens allowed Schreker's 1918 opera to engage directly with contemporaneous anxieties about degeneracy. Franklin points to a moment in Act III concerning a young boy. The instance comes as a mysterious C sharp minor motif leads a small group of rather prudish Genoese citizens onto Elysium in Act III scene 1. The citizens are amazed by the ‘paradise’ island. However, their hushed, hesitant music indicates an unease about the ‘lewd spirits’: erotically arranged marble statues, fauns, naiads, bacchantes and nymphs. Schreker has the boy ask, ‘Who knows, father, they could be angels?’, turning towards his somewhat scandalised parents, ‘as if both mocking and attempting to relieve their prudery’ (Franklin observes).Footnote 62 To take the boy's question seriously: what if the spirits are harmless or even good? Indeed, the citizens will willingly entertain that the fleeting tableaux of mythological creatures represent a finer experience than the pictures hanging in the palace of the late Doge Francesco Sforza.Footnote 63 The aliveness of the island appears to challenge an aesthetic purity signified by the authority of the doge's palace. As Franklin writes, the ‘problem of interpretation and categorisation’ is explicitly thematised in the opera, specifically through the presence of the Genoese in this opening scene, as ‘down-to-earth observers within an over-determinedly “grand-operatic” setting’.Footnote 64 Citing an early prose draft of the opera, Franklin further argues that they – and equally importantly, we, the audience – are the ‘Gezeichneten’, spellbound by operatic late-romantic charms when we are not supposed to be.Footnote 65 The Genoese boldly claim – for us – their desires, which are governed by the apparent baseness of their senses.

As the Genoese are intoxicated by Elysium, their mood becomes ecstatic and their music wild. A critical shift occurs over the course of several scenes in Act III, in the opera's use of masks and the citizens’ engagement with artistic excess: the Genoese appear to leave the stage only to return in ‘a grotesque yet splendid procession of masques’ as the ‘lewd spirits’ they feared and admired at the start of the Act (Figure 1).Footnote 66 The shift begins in scene 11 with Carlotta, whose descending sigh-like ‘Ah, what a night’ and subsequent arch-shaped melodies (b. 518ff.) prove irresistible to all (albeit inaccessible to Alviano).Footnote 67 First echoed offstage by the noblemen Menaldo and Julian/Gonsalvo (the score indicates either), her melodies are then taken up by the choir sopranos’ half-murmur (b. 532ff.). Excitement ensues, and the Youth and the Girl act out (in scene 14) the formula of ‘courtship – resistance – intense pursuit – final surrender’ already outlined in the stage directions at the outset of Act III.Footnote 68 The Youth's musical gestures are reminiscent of Tamare's music, and the young couple's seemingly formulaic liaison ironically underscores the absurdity of heteronormativity and the hegemonic masculine sexual subjectivity it often demands. The whole chorus – the populace ‘in a frenzy’ – come to gather on the front of the stage until the Youth and the Girl join in with them in their intoxicating ‘Oh, what a night!’ before they ‘hurry away into the night … joining with delight in the mightily thunderous singing’.Footnote 69 The effect emphasises the spectacle of excess represented by the Genoese, which defies the ideal of masculine self-containedness.

Figure 1. Photo from Die Gezeichneten's Frankfurt premiere, Act III, ‘Eiland Elysium, Maskenzug’. Reproduced by permission of Deutsches Theatermuseum.

The masked procession properly enters in scene 15. The emphatic beauty of the collective singing comments on the extraordinary beauty of Elysium. However, it contrasts sharply with the crumbling voice of Alviano, who conceptualised the island but now finds himself on it with Carlotta nowhere in sight. Elysium's magic comes to full bloom, then, just as Alviano's fear of losing Carlotta intensifies, and his lapses into declamation signal once again an inability to participate in normative masculinity. As one mask – his bel canto voice – slips away, the other – the beauty of Elysium – is clung to tightly, even when it is no longer desirable. The unstable voice cruelly points to the success of Elysium, his externalised mask. Alviano's desperate cries of ‘Where is she, my betrothed?’ go unheard.Footnote 70 Each of his phrases, which barely sustain two bars (bb. 6052–63 and bb. 6072–82), is first obliterated by the chorus's drunken ‘Ah …’ (bb. 606–72 and bb. 608–91) and subsequently silenced by the orchestra's festive music (b. 609ff.; Example 5). Troublingly, while the Youth's music above already evokes Tamare's, the orchestra actually assumes it ‘with brutal passion’ and ‘in the Italian style’ (b. 660ff.). Given that Tamare's music expresses a masculinity that is overblown and hence feigned, the People's masked celebration can similarly be described as overwrought. Critically, Act III scene 15 is also when the masked (hence anonymous) Tamare catches Carlotta and flees the scene with her. The two modes of masculinity represented by Alviano and Tamare will go head to head, with Alviano finding himself, heartbroken and delirious, confronted by the opera's authority figure.

Example 5. Act III scene 15, bb. 605–610. Franz Schreker Die Gezeichneten © Copyright 1916 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien / vocal score UE 5690

The appearance of the ‘Capitaneo di Giustizia’ near the end of Die Gezeichneten further pushes back against the German remasculinisation project. Amid Alviano's confusion and the People's celebration, the Capitaneo enters in Act III scene 18 as head of Adorno's private army, and his authorial presence only prompts sympathy for Alviano from the citizens. The Capitaneo is an embodiment of Adorno's technocratic militarism and speaks for the ‘judges and upholders of the law’. He is essentially Adorno's double, since the two characters, as Schreker's score indicates, can be sung by the same performer. He charges Alviano with the sex crimes for which Tamare and the rest of noblemen are responsible, yet fundamentally he is also accusing Alviano of degenerate excess: of ‘being possessed by the Evil one and … of having bewitched the people’.Footnote 71 While the citizens have held varying views about Elysium and despite the fact that they have just taken on Tamare's music, they unite here against the opera's representation of masculine power:

You see, that's what it's all about! – They're stealing from us! – They grudge us our pleasure! – Confounded thieves! – Beasts! – (louder murmurs) Down with Adorno! … Alviano, speak! – Defend yourself! – We believe you! – We stand by you! – We will protect you!Footnote 72

The citizens’ comments about theft and intentional depravity here imply a commentary on class conflict and feudalism; indeed, a future study might focus on questions of class division and economic power in the opera, and on these themes in relation to the politics of masculinity in and after the First World War. What is important for the present argument, however, is that when the citizens rally around Alviano, they unanimously show their distrust of paternalism as well as their distaste for the authority's cruelty and macho posturing. The citizens speak as one and implore the opera's audience to sympathise with the opera's most obvious example of deviant manhood. At the end, for all of Tamare's proximity to violence during the opera, it is the ugly protagonist who is driven to commit the ultimate violence on impulse. Alviano fatally stabs Tamare. In this first and final encounter between the two male protagonists of the opera – a moment reminiscent of Wilde's Dwarf's confrontation with the mirror – it is as if Schreker and his audiences confront the horrors of their wartime and post-wartime present.Footnote 73 Momentarily void of orchestral accompaniment and hence musically alone (bb. 1304–14), Alviano, ‘in a completely different voice [is] distraught [and] staggers through the crowd towards the background’ (b. 1320ff.). Alviano's ‘voicing out’ articulates ‘the last hope in the face of the brutalizing anonymity of public masculinity, commercial culture, mechanized production’ in a fragmenting Austria, as Ian Biddle writes in relation to the fin-de-siècle ‘masculinity in crisis’ (though his focus lies in Kafka's and Mahler's creative expressions rather than Schreker's Die Gezeichneten).Footnote 74 Drawn to Alviano's cry and his ever more intensely fragile, sonorously feminised, and hence non-German and non-masculine body, audiences are left wondering about Alviano's fate, just as the final D minor chord resounds.

Degeneracy, and what the critics said

Between Tamare's death and Alviano's descent into madness, Die Gezeichneten offered its first audiences no moralistic resolution. Instead, it opened up possible forms of alternate masculinity at a time when bourgeois notions of martial maleness reigned supreme. Despite the opera's origin before the First World War and its Italian Renaissance setting, Schreker's earliest audiences heard resonances of the war. A number of Schreker's contemporary critics referenced the war in their reviews of the opera immediately after the premiere, including writers at the Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung (Karl Holl), the Dresdner Nachrichten (anonymous) and the Frankfurter General-Anzeiger (Hugo Schlemüller).Footnote 75 Schlemüller went so far as to bemoan ‘the most dreadful war’ at the opening of his review.Footnote 76 Although this line was removed when his review was reprinted in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, his initial comment evidences the proximity between Schreker's stage work and the fears and anxieties brought on by a devastatingly violent though persistently masculinist war. I turn in this section to reviews, like Schlemüller's, of Die Gezeichneten's first performances in Germany and Austria (in Frankfurt and Vienna respectively), and I focus primarily on reviews collected from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.Footnote 77 Just as Schreker's opera explores degenerating manhood, several music critics similarly demonstrate a fascination with qualities of decay – of musical aesthetics, national values and gender norms.

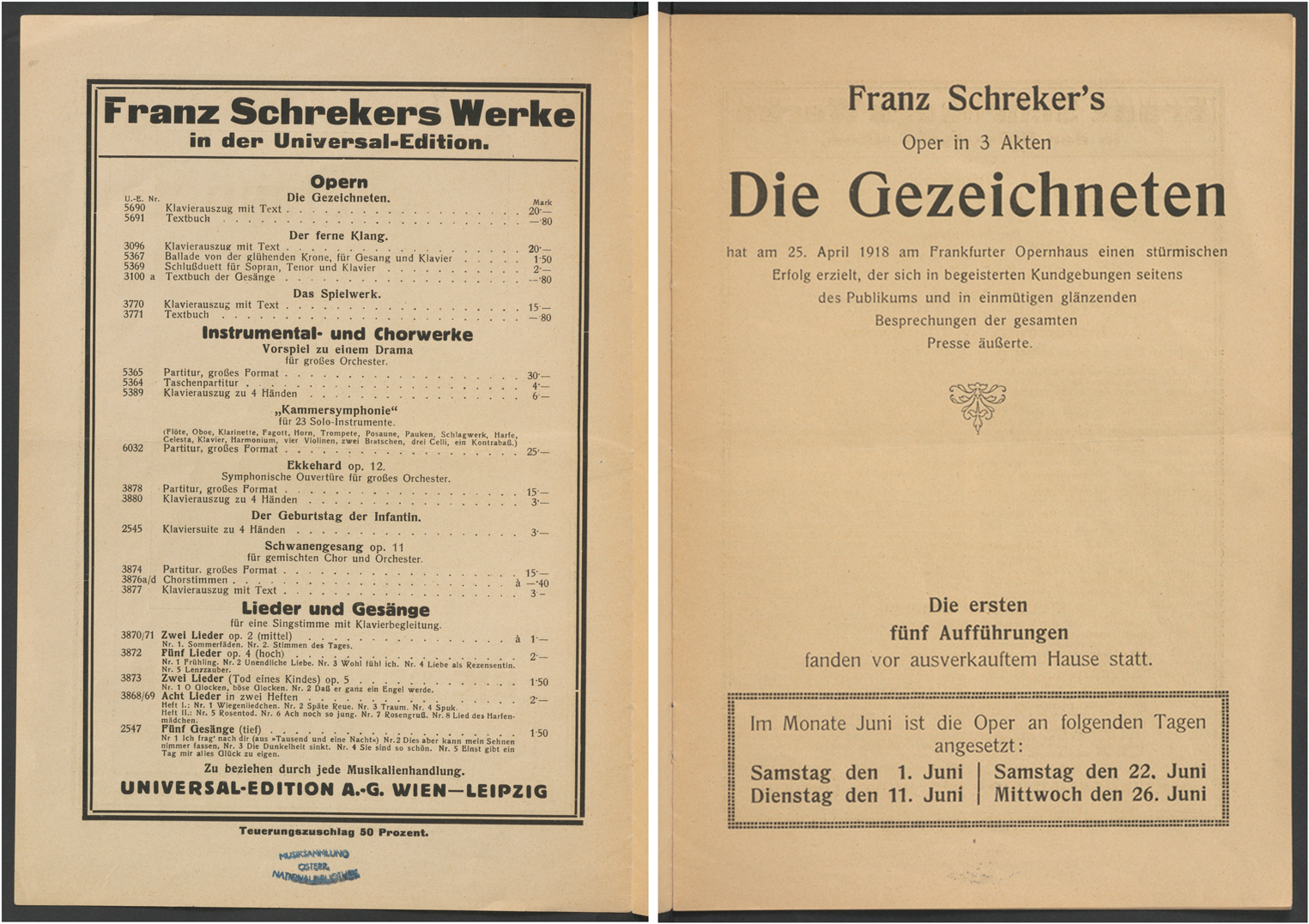

Schlemüller's review was first published in the Frankfurter General-Anzeiger. An excerpt of the cellist and composer's assessment was also included in the booklet of Pressestimmen (press commentaries) issued by Schreker's publisher, Universal Edition (henceforth UE), in May 1918, during the opera's initial runs. Schlemüller began (as many critics did) by reminding his readers of Schreker's recent success with Der ferne Klang (1912).Footnote 78 His focus then shifts, however, to questions of aural pleasure and material extravagance:

Now with his latest opera, Die Gezeichneten, he appears to have achieved the full height of his strange, somewhat extravagant, but deeply and strongly human artistry. He created by himself, from free imagination, his [libretto] book. A poetic work that is, even by itself, a pleasure to read … Admittedly, however, the composer Schreker has just conjured up the right atmosphere with his music. His music is intoxicating and indulges our senses. The last act [is] ripe with emotionalism [Temperament] and unbridled passion.Footnote 79

The remarks on Schreker's ‘strange’, ‘somewhat extravagant’ and ‘intoxicating’ sounds are noteworthy, as these qualities stand in fundamental contrast to the ‘chastity, earnestness, and self-control’ emphasised by modern bourgeois masculinity.Footnote 80

This contrast – and the connection between a degenerate musical aesthetic and a degenerate nation – was sometimes made even more explicit in the early reception of the opera. In February 1920, when Die Gezeichneten arrived in a Vienna that was no longer the centre of an empire but instead only of a small – and deeply insecure – republic, the organist, composer and pedagogue Max Springer brazenly contrasted the opera's supposed degeneracy with the wholesome healthiness of true German art. In his review for Austria's Christian Social newspaper, the Reichspost (a leading antisemitic publication), his desire to affirm a strong Greater Germany is immediately apparent:

While the essence of German music is strengthened by the primal source of melody and rhythm, out of which it draws an indestructible health and vitality to become soul-infused art [Seelenkunst], all of the newer artefacts are built on pathologically over-refined culture, are ill-defined by the nervous stimuli of colour and sound, [and] draw their main nutrients from decadence and weakness. While German art laughs from the blue eyes of a child, flourishes in the bright sunshine of a German spring day, joyous in the forest and meadow, and is found in the most free and wholesome of nature, the nervous art [Nervenkunst] staggers on in its own murky, self-consuming glow, most preferably under the oppressive tropical sun of exotic countries, or it blossoms out of the glaring gleam of a greenhouse. Franz Schreker counts among our most sublime nervous artists, and is above all the best one.Footnote 81

Presented here are discursive clichés of degeneration. Springer juxtaposes musical ‘health and vitality’ with the aesthetics of pathology, illness and nervousness, equating the former with the Germans’ innate virtues and the latter with foreigners’ destructive artificiality. To Springer, Schreker problematically belonged to the second group and was seen as one of its leaders.

The composer himself was prepared for such criticisms. Amid the intensification of nationalist sentiment brought on by Austria and Germany's defeat in the First World War, Schreker was aware of the effect that the war would have on Die Gezeichneten's immediate reception. With more than a hint of wistful self-irony, he therefore commented on both his own un-Germanness and Die Gezeichneten's:

I succumbed – miserable, unpatriotic, un-German fellow that I was, under the spell of my work – to the ruinous influence of Southern magic, and gave Italianate colouring to the Italian setting! The war came, and popular feeling carried over destructively into art. So I became an ‘Internationalist’ … The collapse of Germany, even the decline of our culture, is clearly presaged in the music and in the degenerate character of this work.Footnote 82

In this deliberately overdramatic manner, then, the composer admits that ‘the degenerate character’ of his storyline and musical aesthetic compromises the self-preservation of a war-torn nation. Indeed, Schreker appears to concede that his music was, as another critic wrote elsewhere, ‘morbid’, ‘languorously sensual’ and antithetical to the ‘German element’ of ‘forceful masculinity’.Footnote 83 Yet by engaging directly with debates about health and nation, Schreker acknowledged and even took discursive control of the ‘Internationalist’ qualities attributed to him and his music.

There is something profoundly subversive in the ironic tone of Schreker's commentary. I suggested above that Die Gezeichneten contributed to contemporaneous efforts from other spheres of cultural production (such as Saturn-Film) to challenge the parameters of acceptable masculinity. Here I argue that the composer's self-ironic analysis of his degeneracy tested, in a similar way, the limits of criticism. Schreker's words point to a larger, early twentieth-century cultural-artistic phenomenon of which he was a part, and to which a number of his critics were evidently receptive, including Schlemüller. To draw further attention to Schreker's intoxicating extravagance, in the same review quoted above, Schlemüller cites the composer's enormous orchestra, which included the piano, celesta, bells and ‘all kinds of percussion instruments’.Footnote 84 Yet as the critic continues to describe Schreker's ‘blurred, undefined sounds [with] disappearing tonal consciousness’, instead of condemning the composer, he positively and unreservedly praises Schreker's artistry, not least in nationalist terms. Schreker was thereby no longer a ‘German Debussy’; rather, Debussy should now be called the ‘French Schreker’.Footnote 85 The critic ultimately offers his seal of approval; UE would subsequently include Schlemüller's review in its booklet of Pressestimmen.Footnote 86 Schlemüller's eventual confident embrace of the composer's musical excess suggests a critical fascination with degeneration.

It is worth lingering over the UE booklet (Figure 2). As would be expected from publicity materials, UE's excerpts of reviews were enthusiastic about Die Gezeichneten, and they documented the many standing ovations for Schreker and the performers at the initial performances of the opera. Interestingly, UE was careful to draw readers’ attention to certain passages of these excerpts by printing them in bold, making plain the kind of critical sensibility that the publisher – and perhaps even the composer – considered germane to experience of the opera. It is noteworthy that the bold highlight emphasised the language of degeneration (‘feverish’, ‘confusing’ and ‘overwhelming’).Footnote 87 Daub elucidates this particular mode of critical exploration through a separate review of Die Gezeichneten by Joachim Beck, dated 1919.Footnote 88 In it, Beck described Schreker as a ‘genius in/of decline’, contending that ‘the exhaustion of this second type [the first being one who “starts something”] can have something intoxicating to it as well’.Footnote 89 Since the remainder of Beck's review deploys conventionally affirmative language, Daub contends that Beck's ‘genius in/of decline’, despite its proximity to degeneration, should be read as praise as opposed to criticism. Beck's review arrived too late for UE to include it in its collection, yet together they evidence a prevalence of such engagement with decay. Just as militarised masculinity was defined by what it was not, musical health was co-constituted and in negotiation with degeneration.

Figure 2. UE's Pressestimmen for Die Gezeichneten's Frankfurt premiere. Reproduced by permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Schreker Collection, F3 Schreker 201. (Colour online)

In case there remain doubts about the possible scope of the category of degeneration, I return here, too, to Springer's review. Although the critic would insist on the centrality of a ‘German’ spirit and declare that Schreker's ‘splendid qualities … can presumably only reach their full potential when invigorated by the primal force of German music’,Footnote 90 he would nevertheless almost turn his own opening paragraph (referenced above) on its head and assert that Schreker ‘shows his noblest and most valuable qualities’ in Die Gezeichneten. No longer sick, albeit still somewhat foreign, Springer declares that:

Schreker possesses a rich imagination, a rare sense of sound, a highly developed technical ability, an assured dramatic instinct, one that pours out of a sensual, full-blooded nature and a glowing temperament … Die Gezeichneten signifies the climax of Schreker's musical and dramatic œuvre to date.Footnote 91

The critic thus reclaimed Schreker's music and, because of the intensity of his newfound conviction as well as the speed of his change (in only two half-pages), his shift from one critical position to its almost opposite is remarkable. Springer's untroubled manoeuvre between claims of illness on the one hand and health on the other suggests a critical awareness of the opposition constructed around the figure of Schreker. These two opposites were two sides of the same coin, and Springer was evidently attracted to their interplay. Ultimately, Springer's review signals something in the critic's confidence to employ the language of ‘degeneration’ – not as a weapon to control, but instead because such language actually allowed the subversion of bourgeois values of male-gendered wholeness and wholesomeness.

The questions of masculinity raised by Die Gezeichneten were thus answered by critics who were unintimidated by the presence of degeneration. Given that critics so frequently opened their criticisms in bold, almost insolent terms before settling into more moderate prose, it is possible that the prospect of profit played a role in the music critics’ language. After all, ‘Imitations of [Max Nordau's] Degeneration sprang up in book and article form all over Western Europe’ because, as Alexandra Wilson writes, ‘editors in the burgeoning press realised how effectively they boosted sales’.Footnote 92 Indeed, at a time when sensationalism permeated journalism, there seems to have been a formula that afforded writers a steady flow of readers.Footnote 93 Again and again, a provocative opening was followed by a straightforward presentation of the plot, some measured analysis of the opera, and eventually praise for the performers and the production team. These critics’ collective willingness to engage with the aesthetics of decline should be no surprise. In musicology alone, scholars such as Daub, Stephen Downes and Katherine Fry have shown in their research a steady early twentieth-century interest in questions of decline in Europe, after Wagner but before the consolidation of Nazism.Footnote 94 Outside of musicology, the field of English literature, for instance, has similarly witnessed continual claims of decadence and degeneracy as a legitimately ‘formative force’ – as Vincent Sherry writes – of modernism.Footnote 95 David Weir, moreover, points out that such force is a phenomenon that anglophone scholars are only beginning to grasp following the lead of their Continental European colleagues.Footnote 96 Degeneracy held its own allure.

***

Disfigured soldiers, as noted above, experienced significant political violence on their return from the front. After the First World War, however, these reactions developed into a more extreme moralistic pursuit of aesthetic standardisation.Footnote 97 The masks that facially disfigured soldiers wore, for instance, were no longer enough in the post-war era.Footnote 98 Rather, cosmetic surgeries to improve appearance for the purpose of gaining employment grew increasingly common.Footnote 99 One surgery clinic's advertisement typical of its time thus read: ‘Empty-handed again! … You may have had the skills, but your looks weren't good enough. You have to do something about it!’Footnote 100 These surgeries were not only jointly pushed by middle-class business owners and cosmetic surgeons but also legislatively encouraged by the state through welfare policies and employment laws.Footnote 101 Indeed, the idea that ‘social cosmetics’ could help the ‘oppressed and stigmatised’ was so normalised that even the ruling Social Democratic Party incorporated it into its Weimar-era health policy.Footnote 102 As historians have shown, aesthetic and racial standardisation via sports, dance and nudism in the 1920s brought about ever more violent consequences that culminated in the Holocaust.Footnote 103 We know where it all led:Footnote 104 to an ever more intensified ideology of masculine standardisation and purity that followed the contours of the so-called Sonderweg (special path) thesis.

The reviews cited above are likely what scholars of Entartete Musik today would consider bellwethers of later political persecution. Yet, before the Nazis had control over the language of ‘degeneracy’, the reviews of Die Gezeichneten clearly evidenced a sincere engagement with the concept, finding something in it that was alluring and also, as exemplified by Schreker's opera, possessed of a critical potential to destabilise contemporary moralistic beliefs about manhood. Historian Scott Spector thus provocatively suggests that the end of the nineteenth and the early twentieth century were an age of utopia precisely because of the period's intimate association with decline.Footnote 105 In other words, it was only when the Austrians and Germans felt self-assured enough about the advancement of their social progress that they became positive about confronting decay.Footnote 106 In their confidence at having emerged unscathed from engaging with decline, they saw a composer such as Schreker dispensing with the kinds of moral correctives that Wagner offered in his operas.Footnote 107 Daub therefore rightly sums it up when he argues that the post-Wagnerian ‘genius in/of decline’ told Mime's – instead of Siegfried's – side of the story.Footnote 108 Even during wartime, and perhaps especially because of wartime, then, Die Gezeichneten persisted in its deliberate grappling with topics that were ostensibly too sensational.

The end of Die Gezeichneten inspired no revolutionary ambitions, and the critics likewise were uninterested in artistically induced social change. Instead, they revelled in the opera's refusal to adopt an explicit code of ethics. Indeed, the opera's resistance to being reduced to a moral lesson stems from Schreker's compositional intent. While the Italian Renaissance already occupied an important place in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century German imagination, the Renaissance signified to Schreker a time free from moral judgement. It allowed Schreker to see people as neither good nor evil (‘ich sehe die Menschen weder als gut noch böse’), and it permitted a kind of moral ambiguity that was to him more difficult to find in times before or after the Renaissance.Footnote 109 Then and now, it seems, Die Gezeichneten was and is interesting as a pre-1933 opera because it lets entangled ideas of degeneration (health, gender and nation) stay entangled. Tellingly, Joachim Beck returned again to Schreker's Die Gezeichneten in the 1950s, specifically revisiting his own review of the Frankfurt premiere in order to clarify his views (coincidentally at around the time that Theodor Adorno penned an infamously damning radio essay about Schreker).Footnote 110 In the wake of Nazism, Beck wanted to explain what he meant when he first described the opera in terms of its degeneration. After commenting on the overwhelming but effective orchestral music of the final scenes, he wrote:

Yet, as an objection-conscious young critic, I was curious about – and also opposed to – this orgy of sonic excess and its somewhat nebulous flow. Perhaps my impression of the following evening's premiere was also ambivalent: the sense of being entranced and revolted at the same time.

So I revised my experience of art – great and feverish, but also somewhat morbid and exhausted, and began my newspaper review, forcibly simplified with condemnatory sentences: ‘Genius is strength. Franz Schreker possesses none.’

Strange, however! Even at the time of writing something rumbled inside me. It whispered to me that I did wrong to the work; that a terminal apparition such as Franz Schreker could also have something brilliantly enervating. Indeed, that the physical weakness of the man – similar to Chopin – absolutely yielded the fermenting agent for his music, its luminous character, its innermost value.Footnote 111

Note how this passage lays bare the early twentieth century's allowance for critical ambivalence, the absence of moral absolutes, as well as a sincere flirtation with the sensational and even the repulsive. Beck's 1956 article, then, begs us to consider how, in the pre-Nazi era, critics and artists engaged with markers of degeneracy in deliberately equivocal and even positive terms in spite of a parallel, bourgeois policing of masculinity. Thus, in case his readers still doubted what he meant, Beck plainly asserted: ‘what had seemed negative until then, I now interpreted positively’.Footnote 112

Beck's 1956 words are a reminder of how profound revising the language of degeneration in criticisms of Schreker's 1918 opera could be, even when my reading now comes perilously close to resuscitating the very terms used by the Nazis to dismiss Schreker. In our effort to recuperate music that once bore the loaded label of ‘degeneration’, it is natural for us – scholars of twentieth-century German music – to want to speak forcefully against the evils of Nazism. We should never forget that the Nazis’ politics have shaped Schreker's reception for eight decades, because to do so implies a kind of forgetting that we can barely afford. We want to rescue Schreker from oblivion, because we are invested in reparative justice for ‘Entartete Musik’. Yet while the politics of antisemitism have coloured the language of degeneration, so have the norms of bourgeois masculinity (indeed, anxieties about race and gender are too often entangled). The Nazis have cast a retrospective shadow on the decades before they gained total control, and it has been too easy to read the 1910s and the 1920s as leading inevitably to fascism. Schreker's historiography has been decidedly rooted in the politics of the Second World War. Yet even when the language of Schreker's initial reception so closely anticipates the terms that the Nazis used to dismiss him, this teleological view of history requires a degree of resistance. If Schreker is only read in light of Nazism, other important cultural-historical angles remain unexamined. The concept of bourgeois masculinity, which overlapped with but was not identical to antisemitism, evidently structured Die Gezeichneten and its reception. This article's First World War-centred enquiry seeks, above all, to open up that era's own questions about manhood.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the many helpful comments and suggestions from Joy H. Calico, Timothy Coombes, Christopher Hailey, Brian Hyer, Sherry D. Lee, Ellen Lockhart, Philip Sayers, Arne Stollberg and the five anonymous reviewers who have read versions of this article for this and one other journal. This research has been supported by the DAAD and the Jackman Humanities Institute at the University of Toronto.