The first two decades of the new millennium have witnessed an unprecedented surge of academic interest in the spread of Italian opera to Latin America during the first half of the nineteenth century. The excavation of long-forgotten documents, scattered on both sides of the Atlantic, has opened up perspectives that had for too long remained invisible thanks to the dominance of local nationalism. As a result, the dissemination of the Italian repertoire between 1820 and 1850 has finally come to be seen as a pivotal part of identity-building in Latin America after Spanish colonialism. Soon after the collapse of the Bourbon American empire, Italian opera indeed became wrapped up, to recall Benjamin Walton's words, ‘within a wider search for non-Spanish European civilization’;Footnote 1 the genre served not only to upgrade social and cultural structures within elitist creole communities but also to shape new narratives of international self-legitimation in the post-Napoleonic Atlantic world.Footnote 2 In this light, the encounter between independent Latin America and Italian bel canto has been explored from a variety of perspectives, ranging from the transatlantic routes drawn by European companies, to the urban discourses and political imaginaries built around the operatic stage, to the musical practices of creole men and women.Footnote 3 Each approach has revealed the operatic connectedness of a region once deemed to play a peripheral role in the networks that shaped what Christopher A. Bayly defined as the birth of the modern world.Footnote 4 Yet much remains to be explored.

Original composition has rarely formed a part of this story. There is no doubt, as José Manuel Izquierdo König suggests, that in general nineteenth-century opera was ‘a genre to be performed, not created, in Latin America’: the vast majority of the operas performed in post-independence Santiago, Mexico City or Montevideo were imported directly from Europe.Footnote 5 This strategy responded to creole needs to bring about anticolonial cultural projects and build up a national identity that could not only be ‘“felt as”, but also be “European”’, a word used by creole elites to refer, often interchangeably, to French, British or Italian cultures (but not Spanish).Footnote 6 In fact, though, Italian operas were also ‘created’ – that is, composed – in Latin America in the early nineteenth century.

Many of the librettos and manuscripts of these operas are irretrievably lost, however, while their clear homage to the Italianate style has too often prompted musicologists to neglect them or, worse, to treat them as passive and unoriginal outcomes of European hegemony. Yet although these works are few in number, I argue that they can offer a unique standpoint to rethink the Latin American operatic world in the aftermath of its independence. Indeed, these operas need to be considered not only for their historical significance – most of them played a pivotal role in the cultural self-definition and international legitimation of the new republics in which they were performed – but also for the new insights they provide about the circulation of Italian opera across the ocean.Footnote 7 On the one hand, these operas rebalance the relationship between creole Latin American societies and Italian opera in more symbiotic terms; on the other, they confront us with new questions concerning the production and representation of Italian works in general, highlighting issues raised by bel canto, seen both as a vocal style and as a cultural understanding of the operatic stage, across Latin America from the 1820s onwards. What did creating Italian opera mean in that context? How did bel canto dramaturgies and musical idioms change in contact with creole societies, and vice versa? How were creole dreams of Europeanness and modernity absorbed and transformed in the manuscript and, eventually, on the stage?

These questions challenge any understanding of opera houses in the former Spanish colonies as mere ‘mirrors’ of foreign styles and theatrical habits, and they pave the way towards a more critical approach to operatic performances, understood as ‘complex communicational environments’, in Arvind Rajagopal's terms: spaces not only where musical and performative dimensions of the Italianate operatic tradition became transformed and reinterpreted by creole elites, but also where local postcolonial narratives of past and present could be culturally, socially and politically negotiated and contested.Footnote 8

This article begins from such premises in pursuit not of an overarching theory of operatic composition in postcolonial Latin America – a fairly utopian challenge, given the heterogeneity and instability of the cultural and political context – but, rather, of a microhistory that can shed light on the manifold issues and problems raised by the creation of particular operas. To do so, it focuses on one specific work composed and staged by the Spanish tenor and composer Manuel García (1775–1832) during his stay in Mexico City between 1826 and 1828: Semiramide (or Semiramís, as it soon came to be known among local opera lovers), premiered on 8 May 1828. It was not the only opera composed by García in Mexico: according to James Radomski, the catalogue of Mexican operas by García – the most extensive corpus of operatic works created in Latin America at the time – includes four Italian works – L'Abufar (13 July 1827), Zemira ed Azor (1827?), Un'ora di matrimonio (8 February 1828) and Semiramide (8 May 1828) – and three Spanish ones: Acendi, La jaira and Los maridos solteros, probably the only one to be performed in late 1828.Footnote 9 Semiramide, however, holds a unique position within this catalogue, not only for the amount and variety of documents that survive about it, but also for the role it played historically both in the short trajectory of García in Mexico City and in the restless unfolding of political and cultural events of local creole society in the aftermath of independence.Footnote 10

Manuel García in early republican Mexico City

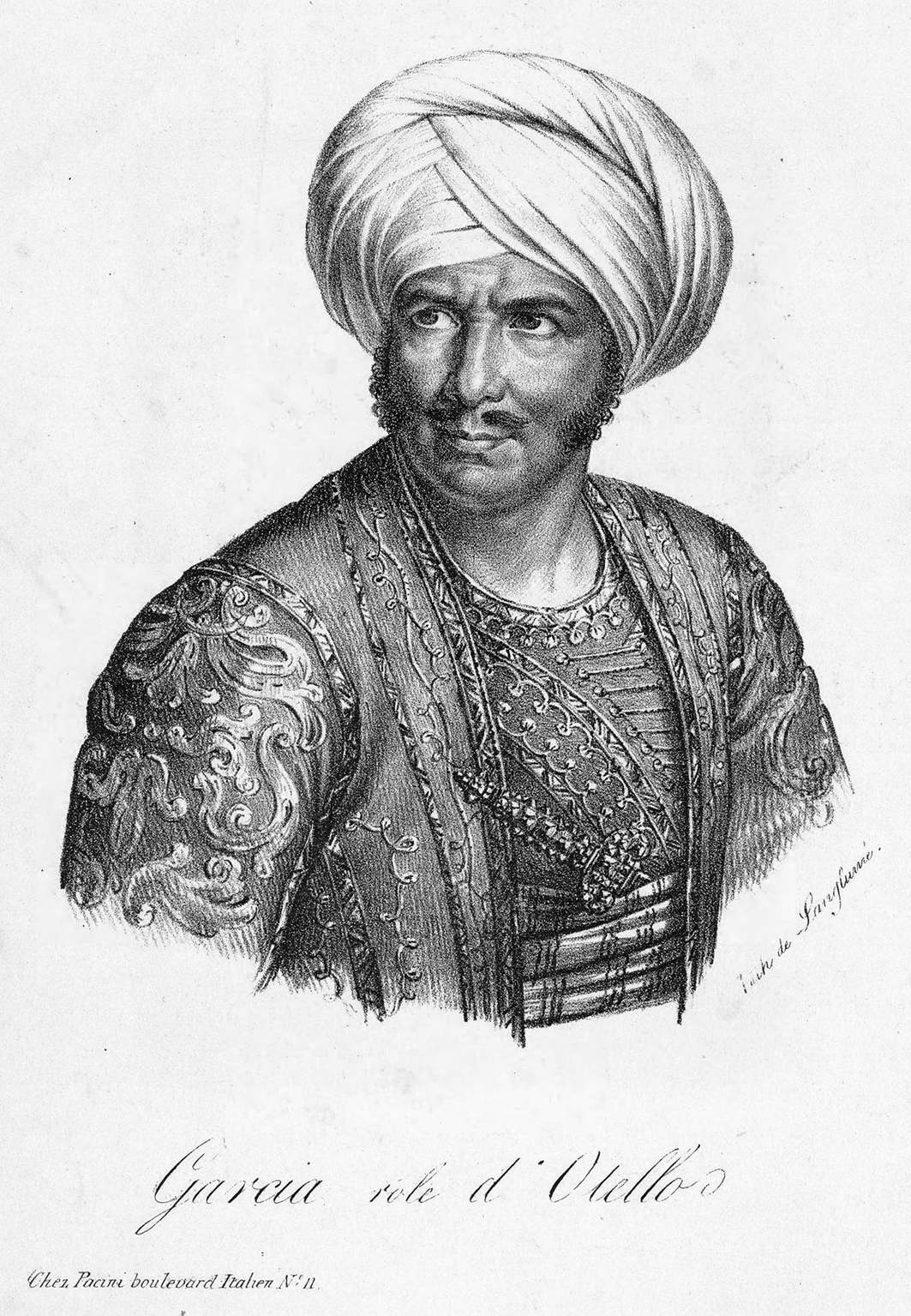

When García arrived in Mexico in November 1826, he was already the ‘compositeur et célèbre chanteur dramatique’ his friend François-Joseph Fétis would later describe in his Biographie universelle.Footnote 11 Between 1810 and 1825, the singer had been the leading tenor in the main opera houses of Naples, Rome, Paris and London, contributing to the creation of important bel canto operas, including Rossini's Elisabetta regina d'Inghilterra (Naples, 1815) and Il barbiere di Siviglia (Rome, 1816) and shaping the success of many others, such as Mozart's Don Giovanni and Rossini's Otello (Figure 1).Footnote 12 To a much lesser extent, his parallel activity as a composer had also contributed to his operatic renown. The Italian operas composed in Naples under the protection of Domenico Barbaja (Il califfo di Bagdad, 1813; Diana ed Endimione and Jella e Dallaton ossia la donzella di Raab, 1814) and in Paris (Il fazzoletto, 1817; La mort du Tasse, 1821; Florestan, 1822) failed to generate much acclaim, but his early Spanish operetas were widely celebrated by the audiences of Paris and London for their ‘exotic’ melodies.Footnote 13 By the beginning of 1825, meanwhile, his activity as a singer began to slow down: critics in Paris and London, including his good friend Fétis, had begun to note alarming signs of decay and fatigue in his voice, signs of which García was sorely aware.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Manuel García in the role of Rossini's Otello (Pierre Langlumé, 1822). Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In autumn 1825, García accepted the opportunity offered by Dominick Lynch, an American businessman and music-lover based in London, to leave Europe and embark on a new operatic project: the introduction of Italian opera to New York.Footnote 15 Yet despite the enthusiastic support of Lorenzo Da Ponte, based in the United States since 1805, North America did not live up to García's expectations.Footnote 16 Unwilling to return to Europe, he looked for new opportunities in the American continent: after rejecting the opera house of New Orleans, in the spring of 1826 García decided to contact some impresarios he had previously met in London and move to Mexico City as the leader of the Compañía de opera italiana.Footnote 17

García, his wife, their son Manuel Patricio and young Paulina – the future Pauline Viardot – arrived in Mexico from New York in November 1826, to find themselves the subject of heightened expectations. The Mexican elites welcomed him as the man who could potentially upgrade Mexico to the same level as European nations.Footnote 18 ‘With the arrival of this company’, wrote a local newspaper soon after the news of his arrival was confirmed by local impresarios, ‘we will have new operas, worthy of the capital of the Mexican republic, where the arts and entertainment are still distant from what we can actually find in more civilised countries.’Footnote 19 These expectations, however, turned to disappointment as soon as García made his debut as a singer with Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia (29 June 1827) and as a composer with L'Abufar (13 July 1827).

The problem was that García had decided to sing both operas in their original language without translating them into the Spanish that the local audience expected: ‘the most ridiculous thing’, commented an opera-goer a few days after the performance of Il barbiere, going on to say that ‘despite being an opera with a Spanish plot, we were forced to see it performed in Italian’, and adding that ‘many Americans in the theatre disliked it as they could not understand most of it’.Footnote 20 While L'Abufar flopped, however, L'amante astuto, premiered in New York in 1825 and revived in Mexico in January 1828 in a Spanish translation, was a moderate success.Footnote 21 Yet language was far from the only issue here: a few weeks later, on 8 February, the premiere of García's third opera, Un'ora di matrimonio – performed in Spanish as Un día de matrimonio – led one opera-goer to remark laconically that ‘I wouldn't like my wedding day to be like that!’ Footnote 22 The failure of this work opens up a broader complex of political debates and cultural differences of the postcolonial transition of Mexico, which in turn help our understanding of the stakes surrounding the subsequent performances of García's Semiramide.

Mexican independence, achieved in 1821 after more than ten years of upheavals and conspiracies, had ushered in a long period of instability and relentless change. The murder in July 1824 of Agustín de Iturbide, the emperor and first ruler of Mexico, opened a new republican phase heralded by a new constitution and the presidential victory of the liberal Guadalupe Victoria (1825–9). His presidency saw significant attempts to launch modernising reforms and give Mexico international recognition in the Atlantic space. Nonetheless, these years were also marked by continual new internal divisions. Earlier debates about which political system would best fit Mexico at the dawn of its independence were soon replaced by new discussions about its future in the ‘international concert of nations’, to recall a popular metaphor in the Mexican newspapers of the time. Some creoles believed that if Mexico wanted to become a modern nation, it had to engage more actively with the political model of the United States, and with the cultures of France and England as opposed to the Spanish colonial legacies. Others instead aimed to situate Mexico under the political and cultural influence of the former motherland. The latter group, mainly old borbonistas and former Iturbide supporters, came to be known as Escoceses, named after the Scottish masonic rite followed by its members. The former, made up of old republicanos endorsed by the North American liberal forces, followed the York rite, which gave them the name of Yorquinos.

By the time of García's debut in Mexico, these divisions had found new outlets in the conflict with their former motherland. Indeed, in the long aftermath of the 1815 Vienna Congress, while other nations attempted to reinstate pre-Napoleonic borders and hegemony, Spain attempted to reconquer Mexico from the fort of San Juan de Ulúa, near Veracruz – an effort eventually endorsed by local Spanish residents in Mexico and pursued by conspirators led by the priest Father Arenas at the beginning of 1827. These events brought to the fore a problem that, despite liberal attempts to hide or destroy physical remnants of the colony, authorities had never successfully managed to address: the status of the Spanish residents in Mexico, disrespectfully known as gachupines. The ruling Yorquino party regarded them as a threat to the stability of the nation and promoted a political narrative aimed at discrediting them while bolstering anti-Hispanic sentiment among creoles. This culminated in May 1827 with the so-called Expulsion Law, which also applied to García, with the result that he went from being the most popular Spanish resident of the capital to being a scapegoat for the whole community of gachupines.Footnote 23

Far from bridging gaps, García's operas exacerbated such conflicts. The local operatic season had been built by García and creole impresarios on the supposedly common ground of Italian bel canto, which constituted the greatest cultural aspiration of the creole elites as well as García's most internationally distinguishing hallmark. Yet their understanding of the concept of bel canto could not have been more different. After a few sporadic and elitist experiments during the Baroque period, Mexico had begun to approach Italian opera more consistently at the end of the eighteenth century, when the enlightened reforms of the Bourbons had encouraged the arrival of new titles by Paisiello, Cimarosa and other masters of the late Neapolitan School.Footnote 24 After their arrival in Mexico these operas usually underwent a process of transformation in line with the laws issued by the government of Madrid, which aimed to ensure stronger stability and cultural homogeneity across the empire.Footnote 25 Italian and French librettos were translated into Spanish, often transformed into zarzuelas (with prose dialogues instead of recitatives), split into further sections to facilitate listening and interspersed with local dances and songs.Footnote 26 These conventions soon became an operatic habit and, later, a tradition that remained unchanged even after the turmoil of independence.

During the first wave of Rossinian operas in Mexico, between 1823 and 1826, creoles continued these colonial traditions without ever questioning their suitability either in relation to the ongoing European practices that they sought to imitate, or to the Spanish past they were trying to erase. Not even the arrival of Stefano Cristiani, the first Italian composer to work in postcolonial Mexico City, changed this perception of the nature of Mexican operatic italianità: though born in Bologna and educated by Paisiello and Cimarosa, he landed in Mexico in 1823 with a strong Spanish musical identity after many years in the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 27 The operas he performed in Mexico City – El solitario (composed and premiered there in 1823), El tío y la tía and Ramona y Roselio (both imported from Spain) – were deeply influenced by Iberian traditions in ways that Mexicans perceived as familiar: all were sung in Spanish, with prose dialogues instead of recitatives and the latter two were based on librettos inspired by Spanish enlightened literature. Although Spanish by birth, Manuel García came from a very different background, with a long and prestigious experience with Italian operas in Naples, Rome, Paris and London. As a result, his understanding of Italian opera was very different from that of Mexican opera-lovers, as emerged dramatically after the premiere of Il barbiere and L'Abufar.

These misunderstandings were further complicated by the political labels that Mexican elites had attached to Rossinian and pre-Rossinian operas as a consequence of the postcolonial transition. Cimarosa and Paisiello had become extremely popular in Mexico during the final decades of Spanish colonialism; after independence, their operas were seen as vessels for colonial values just as Rossini was simultaneously transformed into a byword for postcolonial liberal sympathies. During the 1820s, their names and their music became markers of political beliefs: hispanophile and conservative factions gathered around Cimarosa and Paisiello (and therefore also Cristiani, who had studied with both between 1790 and 1799) to defend the proportion, balance and harmony of good music against the supposedly erratic language of Rossini.Footnote 28 Likewise, progressive and liberal thinkers opposed Rossini to Cimarosa, Paisiello (and, again, Cristiani) in the name of the sort of cultural progress and modernisation for which Mexico had been waiting for too long: ‘is it a sign of modernity that there are still … those who say that El solitario by Cristiani is much better than the operas of Rossini?’ queried an anonymous opera-goer provocatively in 1825.Footnote 29

When he settled in Mexico City, García had no concept of these debates and acted according to his own experience. As an Italianate composer, he had been educated in the pre-Rossinian world: his Italianate operas Il califfo di Bagdad (1813), Diana ed Endimione and Jella e Dallaton (both 1814) were composed and premiered in Naples before the arrival of Rossini in 1815, following a repertoire of styles and forms codified by composers such as Ferdinando Paër, Pietro Generali and Johann Simon Mayr, as well as Cimarosa and Paisiello. With the European success of Rossini, García the composer failed to adapt his language to the new stylistic turn, and instead gave up Italian opera, shifting instead to French repertories (Le prince d'occasion, 1817; Le grand lama, 1820; La mort du Tasse, 1821). When he landed in Mexico, García resumed the role of Italian composer, and returned to his earliest models. The nostalgic ears of some Mexican conservatives and pro-Bourbon newspapers struggled to conceal their enthusiasm for the first results of his activity: they praised ‘el célebre García’, who – as reported in El observador de la república mexicana at the end of July 1827 – ‘successfully overcame all odds’ to give Mexicans operatic performances of the highest quality.Footnote 30 The majority of García's audience, however, felt confused and disappointed: his operas not only failed to sound Rossinian but seemed to hinder their cultural aspirations for the new nation. In September 1828, for example, Rossini's Il barbiere was scheduled in the afternoon so that García's opera El amante astuto could take the more prestigious evening slot. As soon as the schedule was announced, the liberal newspaper El correo de la federación mexicana summarised in the following terms: ‘So, now Italian opera is performed in the afternoon and second-rate opera by night? Oh! What a mistake!’Footnote 31

Waiting for Semiramide

Semiramide was designed to resolve all these tensions at once. After months of hostility and critique, García hoped to restore his identity as a modern Italianate (i.e., Rossinian) composer in Mexico and silence his anti-Hispanic opponents. Liberal creole elites, for their part, hoped finally to have an Italian opera that everyone would enjoy and talk about, while giving a major boost to their national project of cultural modernisation and the definitive eradication of colonial values. With Semiramide, Mexico City could finally be compared to the richest cities of Europe, not only as an importer, but also as a creator of Italianate operatic masterpieces. Its premiere at the newly refurbished Teatro de los Gallos was one of the biggest events of the 1828 operatic season in Mexico City. Opera lovers and politicians alike had been eagerly looking forward to it since March, when the rehearsals had begun. On 7 May, the day before the performance, El sol reminded its readers that ‘tomorrow the great opera La Semiramís will be premiered in Spanish’, and the following day, a few hours before the premiere, El correo de la federación mexicana heightened the anticipation with cynicism: ‘This evening we will have a performance of the famous opera La Semiramís in Spanish. We hope that the performance will hold up to all the fanfare with which it has been announced!’Footnote 32 These two announcements clearly emphasise the excitement around Semiramide at the time. Until then, no opera, not even favourites such as Rossini's Tancredi and L'italiana in Algeri (both premiered in 1823), had been announced with such pompous rhetoric; the adjectives ‘famous’ and ‘grand’ had never been used before in Mexico to introduce a new operatic composition.

Such rhetoric, of course, was not without reason. These expectations stemmed, first of all, from Semiramide's close resemblance to Rossini's setting of the same libretto, premiered at La Fenice in Venice in 1823. It is worth underlining, however, that Rossini's opera had not yet been staged in Mexico, and would not premiere for another four years, in 1832, with the Italian bass Filippo Galli and his company. A few arias and the overture were probably circulating in domestic spaces through piano transcriptions, however, alongside newspaper reviews from performances in Europe that consolidated the opera's reputation as one of the most paradigmatic examples of bel canto.Footnote 33 With García's work, the aura of Rossinian bel canto could therefore materialise as a local product, re-composed by a famed European operatic star who had been close to Rossini himself as a colleague and friend. The new opera had all the necessary preconditions to become the momentous success everyone was expecting: a prestigious libretto recently set by Rossini, and a company with a core of European singers as well as an imported scene painter. For the 1828 season Manuel García had assembled a new company which included, aside from himself and his wife (Joaquina Briones) as Idreno and Semiramide respectively, the Spanish soprano Rita González de Santa Marta as Arsace, and a group of Spanish and Mexican singers: Andrés del Castillo (Oroe), Joaquín Martínez (Assur) and Amada Plata (Azema).Footnote 34 Finally, the company was complemented by the French scientist and artist Frederick Waldeck, a painter in the service of the company who designed the scenes, props and costumes for the principals and chorus. However, the highest expectations were for García himself, as composer. After failing with his previous operas, it was hoped he would compose music for Semiramide on the model everyone wanted: Gioachino Rossini.Footnote 35

Around Rossini: a new music for Semiramide

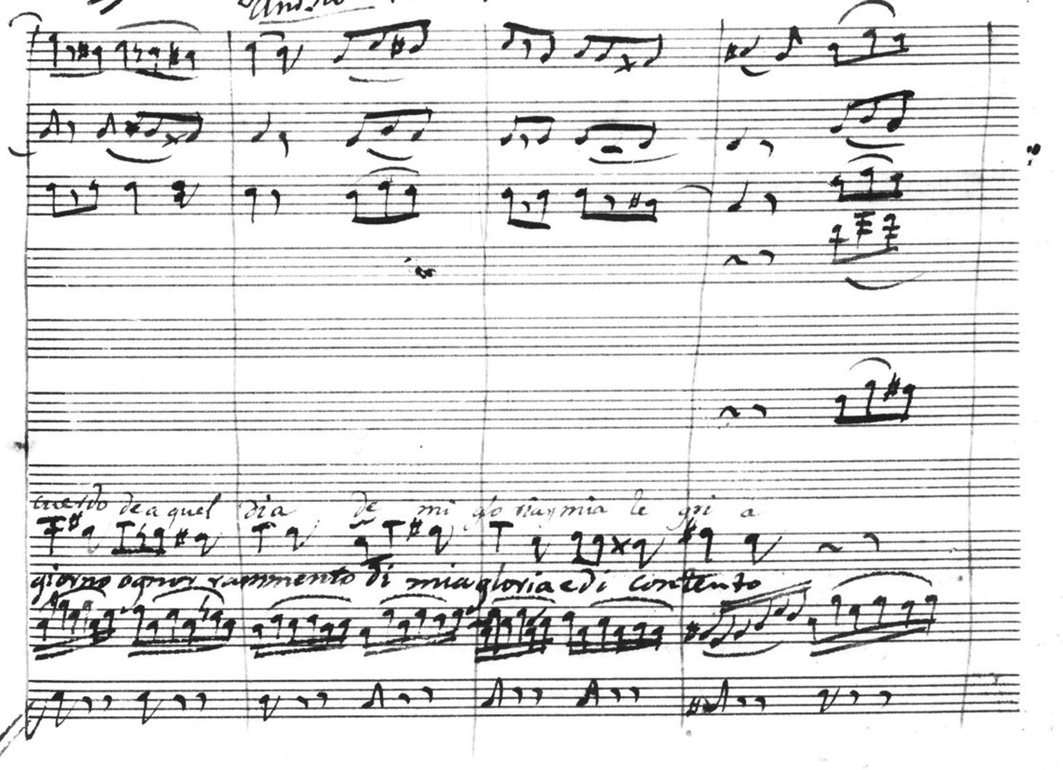

In 1828, when García started composing the music for Semiramide in Mexico City, Rossini had become increasingly popular, at the expense of composers of earlier generations such as Stefano Cristiani, Giovanni Paisiello and Domenico Cimarosa. Even the most conservative contributors to the main cultural magazine of Mexico, El iris – once a staunch defender of the classicist school of Mozart and his Italian contemporaries – had to surrender and acknowledge the widespread success of his music. As the Cuban-born poet José María Heredia wrote about Tancredi at the time: ‘I doubt there's still anyone who does not know this beautiful composition [which] can be found and listened to wherever there is a piano.’Footnote 36 García too had to come to terms with Mexico's musical obsession, and instead of stubbornly pursuing his own idea of opera based on pre-Rossinian models (in line with those of Cristiani), he finally decided to indulge the dominant tastes of the time. The choice of Rossi's libretto already constituted a very clear gesture of compromise, but not enough for audiences whose experience with Rossini demanded a much deeper and more consistent approach to his music. The manuscript of Semiramide suggests, in fact, that García emulated the Rossinian model on two different levels, structural and stylistic. The following sections will analyse both, through examples from the manuscript score.

As far as the structure of the opera is concerned, García followed Gaetano Rossi's text closely, retaining not only the entire theatrical distribution of the scenes, but also the inner structure of individual numbers. He therefore kept the cabalette, strette, duets, concertati and recitatives unchanged from the Rossinian model. Although this might seem a superfluous remark, García's adherence to the original libretto is notable in light of contemporary Mexican practices of changing the structure of Italian operas. Moreover, García divided the two-act libretto into three only in order to make room for intermissions (presumably consisting of tonadillas, local dances and popular songs), consistent with Mexican operatic traditions.Footnote 37

García's efforts to comply with the Rossinian model became more evident in the overture. He knew that expectations would be high for Semiramide, especially after the misstep of his previous operas: L'Abufar (July 1827) and Un'ora di matrimonio (February 1828) had each begun with a very short musical introduction connected with a chorus or an ensemble from the first act. This decision had presumably been made to emulate the latest Neapolitan operas by Rossini (Ermione, Maometto II, La donna del lago, etc.). However, with the exception of Otello (one of the few Neapolitan operas to start with a proper overture), which premiered in Mexico City in January 1827, and a few arias from La donna del lago and Armida performed during academias, this more recent repertoire and its innovations were barely known in Mexico City. Thus, by taking this repertoire as a model, García not only unsettled creoles’ conception of Rossinian music but also deprived them of one of their favourite moments in an Italian opera: the overture, with its self-contained form and abundance of catchy tunes, suitable for theatres as well as for private performances in piano or guitar transcriptions. While the absence of the overture in L'Abufar went unnoticed, overlooked in the general discussions about translation, García was eventually asked to add a new overture in Italian style to Un'ora di matrimonio. This request is indicative not only of the importance of this element for Mexican audiences, but also of the effect of such debates on García's compositional decisions.

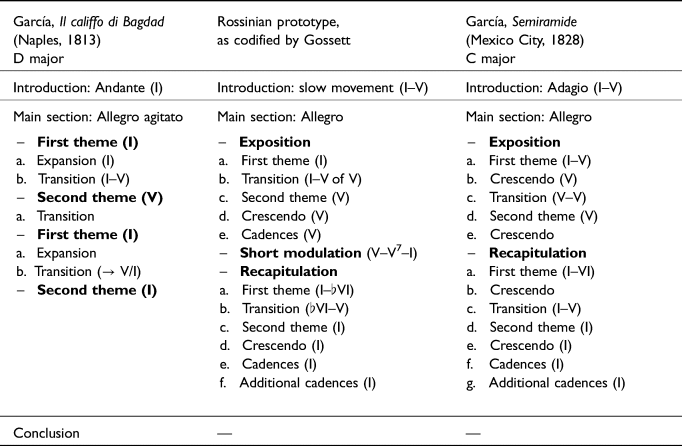

In order to meet Mexican expectations, García composed an overture based on the favoured model, namely Rossini's early repertoire of Tancredi and L'italiana in Algeri. Table 1 demonstrates how García shifted towards early Rossinian models, by comparing the structure of three different overtures: García's Il califfo di Bagdad (Naples, 1813), by far the most representative and successful of his Italianate (pre-Rossinian) operas; the Rossinian prototype codified by Philip Gossett as the ‘archetypal form’ as it emerged in the overtures of Tancredi and L'italiana in Algeri; and the overture from Garcìa's Semiramide.Footnote 38

Table 1. Comparison of overture structures

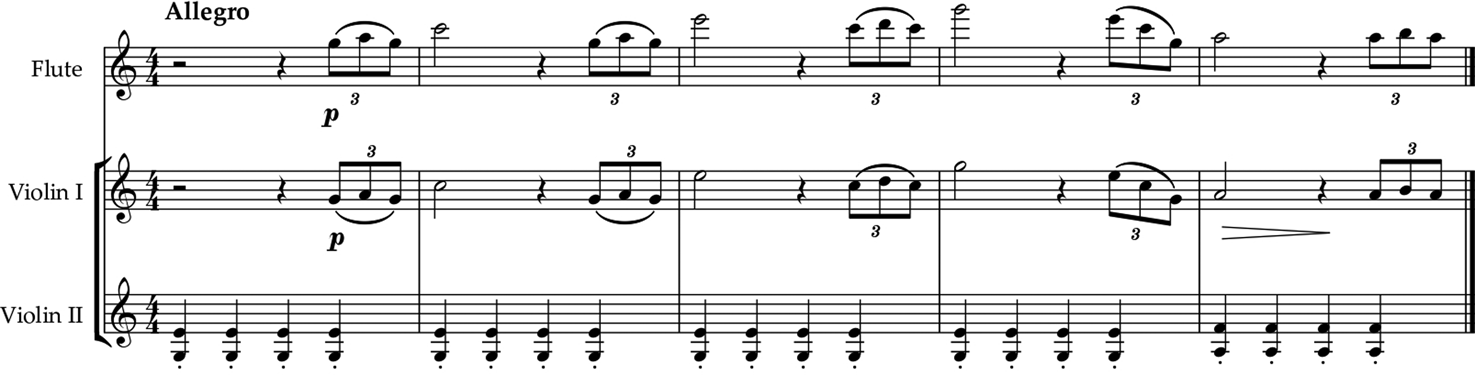

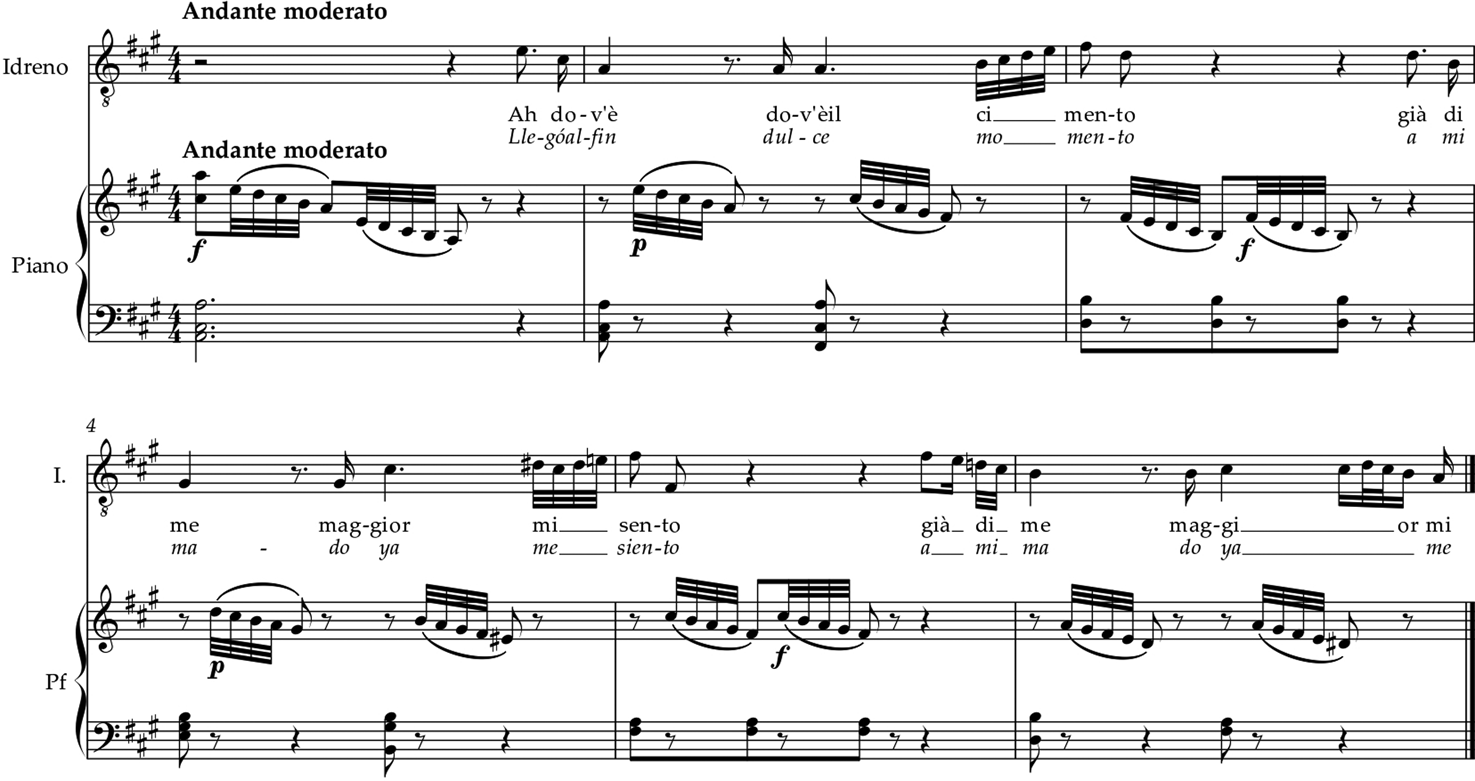

Similarity to Rossini also became necessary at a stylistic level: although García had already approached the Rossinian style with the two operas composed in New York, L'amante astuto (1825) and La figlia dell'aria (1826), the pressure of Mexican audiences forced García to move away more radically from the style of Johann Simon Mayr and Giovanni Paisiello, his main references during his activity in Naples between 1810 and 1815, and towards the new and increasingly globalised style of Rossinian operas. This move resulted in the introduction of a wide array of details that explicitly resembled patterns used and popularised by Rossini. For instance, in the slow introduction after a loud chordal section, the strings start a pizzicato run of quavers under long woodwind intertwined melodies (Example 1) that resemble the same section of the overture of Rossini's Tancredi (Example 2), a favourite of Mexican audiences. Similarly, the opening of the first theme of the exposition and recapitulation replicates a gesture of a base of crotchets in staccato to accompany solos or duets of wind instruments (Example 3) that Rossini's first overtures had already turned into a hallmark of the new Italian style.Footnote 39

Example 1. García, Semiramide: overture (bb. 9–12).

Example 2. Rossini, Tancredi: overture (bb. 11–15).

Example 3. García, Semiramide: overture (bb. 35–9).

The crescendo provides further details about the influence of Rossini's music on García's Semiramide.Footnote 40 Working as a composer in Italy (1810–15), García had employed the crescendo only on a few occasions. Il califfo di Bagdad, for instance, includes a few crescendi used as short dynamic expedients and had nothing in common with the Rossinian technique described by Emanuele Senici, as a ‘quintessentially repetitive device, relying as it does on the progressively louder reiteration of the same phrases’.Footnote 41 With La figlia dell'aria and Un'ora di matrimonio García had already begun to explore this device more attentively, but it was only with Semiramide that his adherence to the Rossinian model became quantitatively and qualitatively more obvious. In the overture, for example, he used crescendi at the end of the first theme (precisely where Rossini would usually insert a short one, under the transition between the two themes) and at the end of the second theme. More interesting is the way García deploys this device elsewhere. The central section of Idreno's second aria ‘La Speranza più soave’ is particularly eloquent: García repeats the same pattern of two semiquavers for eight bars. The whole crescendo is then spiced with another quintessentially Rossinian nuance, as the strings play ‘al ponticello’ (Example 4).

Example 4. García, Semiramide: Idreno's aria (Act II bb. 64–72).

Rethinking Italian voices

García's relationship with Rossini's music became more problematic when it came to matters of vocality. A comparison of L'Abufar and Semiramide, the first and the last of the Italian operas García composed in Mexico City, exemplifies the matter, and prepares the ground for further analysis. The first comparison is between the opening of the two soprano cavatinas for Salema and Semiramide (Examples 5 and 6). Examples 7 and 8 compare the entrance of Faran, the primo tenore of L'Abufar, with the second aria of Idreno – both roles that García wrote for his own voice.

Example 5. García, L'Abufar: Salema's cavatina (Act I bb. 25–35).

Example 6. García, Semiramide: Semiramide's cavatina (Act I bb. 17–26).

Example 7. García, L'Abufar: Faran's cavatina (Act I bb. 1–7).

Example 8. García, Semiramide: Idreno's aria (Act I bb. 17–22).

As a performer, García had long worked with Rossini. He therefore knew very well the vocal hurdles and allures of his operas and how to translate them into a vocal score – as Salema's and Faran's cavatinas from L'Abufar clearly demonstrate. Yet with Semiramide, García seems to take a different route, revealing a noteworthy simplification in the vocal writing, not only in comparison with Rossinian operas, but also with García's previous opere serie premiered in Mexico City. One might argue that the advanced age or lack of experience of some of his company's members could have led García to write less virtuosic arias. This may be true for the role of Oroe, for instance, written for the aging Spanish singer Andrés del Castillo (based in Mexico as an actor since 1802), but not for the rest of the company. Santa Marta, who sung García's Arsace, was born at the beginning of the century in Barcelona, which had the most Italianate operatic stage in the Iberian Peninsula, and as a young woman she would have heard Italian singers such as Teresa Schieroni, Carolina Pellegrini and Ranieri Remorini on stage there. Joaquina Briones, meanwhile, although overshadowed by the successes of her husband, had a solid operatic curriculum: from 1810 to 1825 she had sung operas by Rossini and Paisiello with renowned singers such as Isabella Colbran (García's Il califfo di Bagdad) and Francesca Maffei Festa (Paisiello's La molinara, Paris, 1810) among others.Footnote 42 As for García, although by this point showing distinct signs of vocal decay and fatigue, he was still able to perform demanding bel canto roles. Not surprisingly, on his return to Paris in Spring 1829, he was invited to sing operas such as Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia and Mozart's Don Giovanni. Footnote 43 If most of the members of the company were perfectly capable of performing virtuoso arias, why did García write such a linear and unornamented line for Santa Marta for the entrance of the protagonist in an opera that Mexicans wanted to be the paradigm of Italian bel canto? And why did he shift from a highly virtuoso entrance (Faran) to an accessible vocal line for Idreno?

I suggest we might find the answer to these questions in the reception of operatic singing in Mexico City during its transition from colonialism to independence. As recently argued by Claudio Vellutini, the circulation of bel canto outside Italy during the third and fourth decades of the nineteenth century triggered responses ‘that reshaped, reimagined, and at times fictionalized singers’ personae, their performances on stage, as well as their voices’.Footnote 44 In Latin America, however, these responses were largely conditioned and complicated by the remnants of colonial theatrical practices. The first Italian works performed in Mexico City at the end of the eighteenth century under the wave of new enlightened reforms were sung in Spanish, by creole or Iberian singers who had little or no experience with Italian bel canto and therefore modified the vocal score according to their needs and personal skills. Most of these singers survived independence with their own vocal practices intact: when the theatres of Mexico City reopened in 1823 nothing seemed to have changed in this respect since the last curtain call in 1817.

For European travellers, the result of this continuity sounded bewildering, even appalling. The British tourist William Bullock, who visited Mexico City in 1824 and attended a theatrical show at the Teatro Principal, deemed the performers ‘below mediocrity’.Footnote 45 A few years later, in May 1826, Frederick Waldeck, who eventually collaborated on the props and costumes for García's Semiramide, attended a performance in Spanish of Boieldieu's Le calife de Bagdad in May 1826 and described it as ‘abominablement représenté’.Footnote 46

Creoles looked at their singers from a different perspective, which was largely conditioned by the visual legacies of their colonial traditions imported from the vast repertoire of spoken theatre (autos sacramentales, comedies and tragedies) and dances of creole, Iberian and African origins. Opera was not exempt from this approach: more often than not, the performance of sainetes, tonadillas and Italian works was supported by the bodily gestures inspired by the long mime tradition of Spanish popular theatre. After independence, practices and companies initially remained unchanged, so when Mexico established more direct contact with Italian opera without the mediation of Madrid, creole music lovers struggled to understand the predominance of the voice over any other component of the performance. In 1826, a few days after the debut of Rita González de Santa Marta in the title role en travesti of Rossini's Tancredi, Jose María Heredia published an extended report on the performance in El iris. After brief praise of the opera, Heredia shares some opinions about its visual representation on stage. He first attacks the male clothes Santa Marta wore as the reason for her vocal uncertainty and the incomprehension of the audience: ‘we should also bear in mind the inevitable personal turmoil of a lady who for the first time enters the stage dressed as a man, in front of an intimidating audience’. He criticises other aspects of the staging, in surprising detail: ‘It seemed utterly inappropriate and ridiculous to see a pink helmet and armour on Tancredi at the end of the parade, in which he was carried on people's shoulders, like a Mexican saint, for his victory against the champion of Syracuse, the noble Orbazán [sic]’. He concludes with a straightforward question that remains unanswered: ‘When will we have a decent and appropriate staging?’Footnote 47

Heredia's approach exemplified a common way of understanding Italian opera in late colonial and postcolonial Mexico City. Back in 1806, the thinker and politician Fray Servando Teresa de Mier (1763–1827), one of the first Mexicans to travel to Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century, before independence, visited Paris and attended a performance of Les mystères d'Isis, the French adaptation of Mozart's Die Zauberflöte. Recalling the event in his memoirs, he very carefully picked out details to share with his fellow readers in Mexico, skipping the voices to describe instead the lavish staging he saw: ‘there were one thousand female dancers for the ballet and they spent 700,000 francs on props and costumes!’Footnote 48 Twenty years and an independence war later, visual aspects continued to be prioritised: despite the debates fuelled by García's debut with Il barbiere di Siviglia, creole opera-goers appreciated the improvements he had brought to the staging – ‘well staged, decorated and painted’ – and they did not comment at all on the voices of the performers.Footnote 49

Babylonia on a Mexican stage

In this light, García might have deemed the display of sophisticated singing unnecessary for audiences with a different understanding of the operatic stage. Indeed, he decided to prioritise the visual dimension of his new Semiramide, with financial support granted by the municipality for the occasion. By February 1828, when the manuscript score was finally ready and the company had already commenced rehearsals, Waldeck started work on the decor. Despite everyone's enthusiasm for the new opera, he embarked on this project with few expectations about the outcome: ‘I have worked all day on the sketches for the decor for Semiramis but it might be wasted time.’Footnote 50 Unfortunately, none of the props or sketches by Waldeck have survived; what remains is the list of props used for Semiramide and other Italianate operas staged in 1828.Footnote 51 A close look at this list allows us to compare the number and the quality of props used for Semiramide with those for other operas performed during the season.

Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia, for instance, required only a room with six wings and one canvas representing a street. The performance of Otello included one panel with holes (for windows, doors or arches) and six wings, a semi-circular canvas, wooden stands with little canvas wings and two floorboards. The props for Mozart's Don Giovanni, premiered by García in the summer of 1828, included four panels with holes to represent hell, one garden curtain, one canvas with moonlight and six little transparent wings, one wooden horse with stirrups for the statue of the commendatore, one wooden balcony and a canvas, one door with its wing. A similar amount of props was required for García's first opera L'Abufar: one encampment background, one canvas of a forest, one curtain, three tents, two blades from Mineral del Monte (one of the main centres for silver extraction near Mexico City), one pine and one palm tree, one sepulchre, plus a sun and one storm box. García's Semiramide, however, required a much larger number of props, which the anonymous copyist lists on several pages.

• Costumes for ladies: eleven skirts, twelve tunics, twelve belts, nine handkerchiefs, twelve laurel wreaths.

• Costumes for men: eleven green tunics, eleven aprons, eleven cloth caps.

• Costumes for priests: eight white tunics, dark cloaks, blue belts, head bands with flames, handkerchiefs from Hamburg.

• Costumes for Egyptian soldiers: six blue robes with small woollen tunics, six head bands, six handkerchiefs from Hamburg.

• Costumes for Greeks: six small white tunics, pink bands, pink cloaks, six yellow head decorations, eight pairs of boots with yellow decorations.

• Costumes for Indian soldiers: eight golden robes, eight woollen necklaces, eight sheepskin caps.

• Costumes for Indians: two yellow coconut tunics and belts, two short white trousers, two purple cloaks.

• Props for Waldeck: one tunic with feathers, a cloak, a shaman costume from the opera Don Juan, two curtains with braids, two dressing tables, one oil lamp, one candle holder, four silver desks, two candlestick holders, fourteen fine sofas (one broken), nine ordinary sofas.

• One cabinet background.

• Four wings, new canvas and wings for the house.

• One hall background with six wings for the house.

• One background with a sepulchre painted on the canvas for the encampment L'Abufar.

• One garden painted in the forest for L'Abufar with its wings.

• Six new drop scenes for the Temple. One new wooden statue of the God of Babylonia, two similar new statues and two medium statues with a painted pedestal.

• Six wooden columns.

• Three grandstands.

• Two painted court walls.

• One painted rose bush for the garden.

When the work opened on 8 May 1828, a sumptuous stage appeared before the audience gathered at the Teatro de los Gallos, with more than thirty different props and individual decors, from exotic temples to statues and gardens, and dozens of costumes for the colourful crowds of Indians, priests and warriors in the background. Although no information concerning the costumes has survived, the list of objects and clothes conceived by Waldeck for Oroe gives a hint of how richly adorned Semiramide, Arsace and Assur might have been on stage. Moreover, García and the municipality spared no expense to ensure a better quality of products to represent the biblical city of Babylonia: while most productions were staged with canvas and wings borrowed from other productions, Semiramide used brand new props and costumes, assembled, built, painted, or even imported specifically for that occasion from Europe.

Semiramide in translation

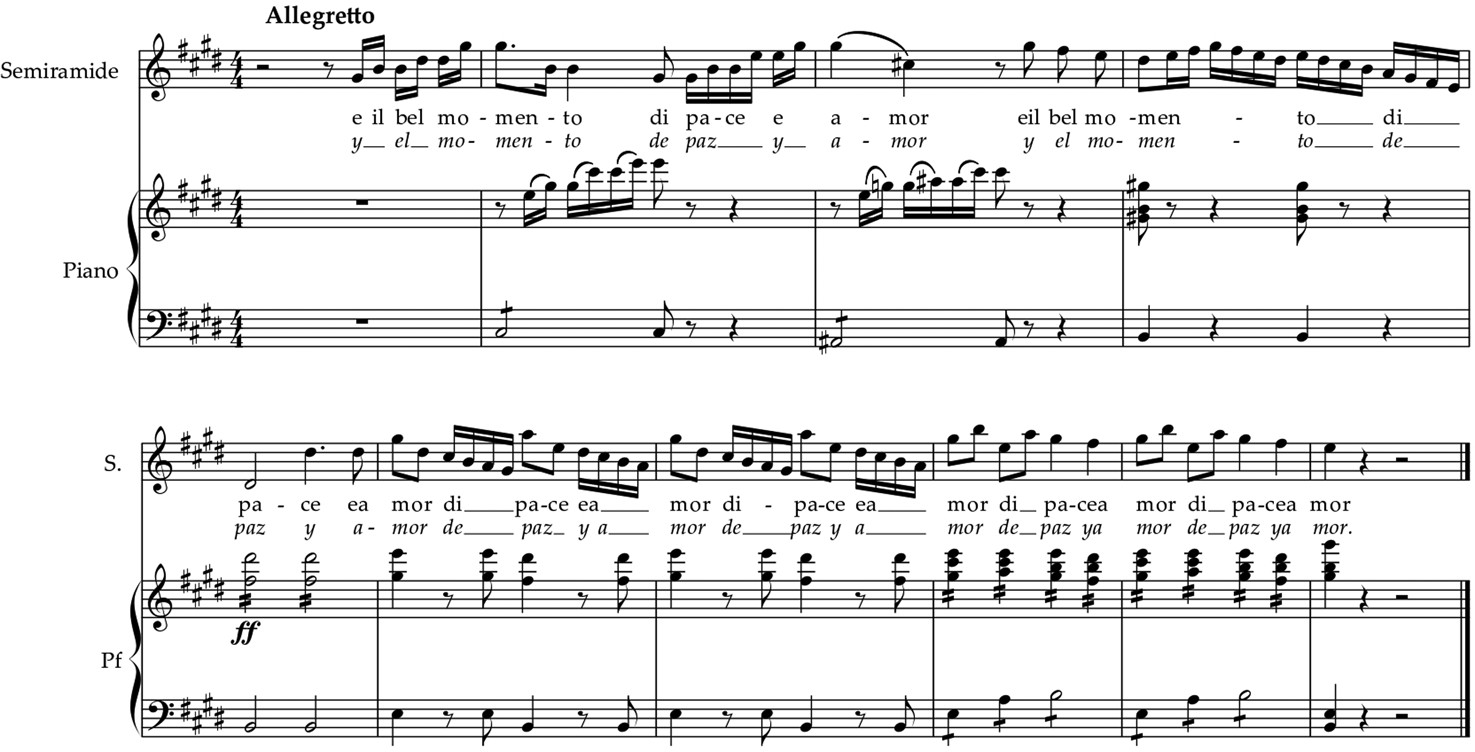

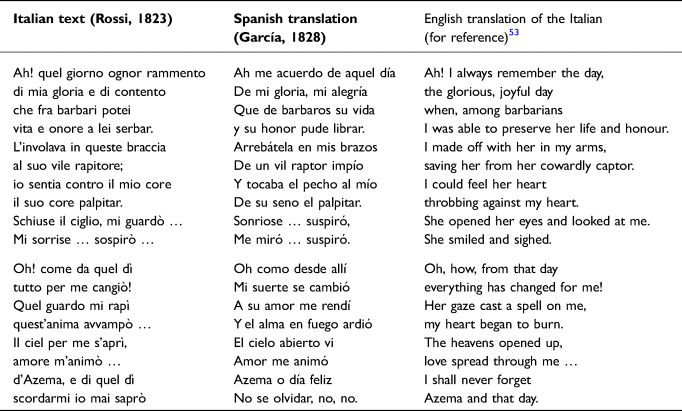

Once the music was composed and the scenes of Semiramide were being set up on stage, García worked on a final but crucial adjustment loudly requested by the audience of Mexico City: the translation of the libretto into Spanish.Footnote 52 The premieres of Il barbiere and L'Abufar had fragmented the cultural intelligentsia of Mexico City into two factions: on the one side, those who believed that the musicality of Italian language had to be preserved by printing the libretto with the translation next to the original, as was already happening in the main European capitals outside Italy, and, on the other, those who claimed that singing an opera in its original language did not allow the audience to understand the plot of the opera.Footnote 54 The latter view soon prevailed and García finally surrendered to their requests. L'amante astuto and Un'ora di matrimonio were quickly translated by adding the Spanish version below the Italian in the score.Footnote 55 The translation of Semiramide was, however, more problematic: creoles’ great expectations for the new opera together with the popularity of Rossi's libretto convinced García to take unprecedented care and aim to retain both the musicality and the dramatic power of the original – as demonstrated by the following examples. The first is Arsace's aria and cabaletta from the first act, ‘Ah quel giorno ognor rammento’, translated by García himself (Table 2, Example 9).

Example 9. First bars of Arsace's cavatina from García's Semiramide (Act I scene 4).

Table 2. Italian text with García's Spanish translation for Arsace's cavatina from Semiramide (Act I scene 4)

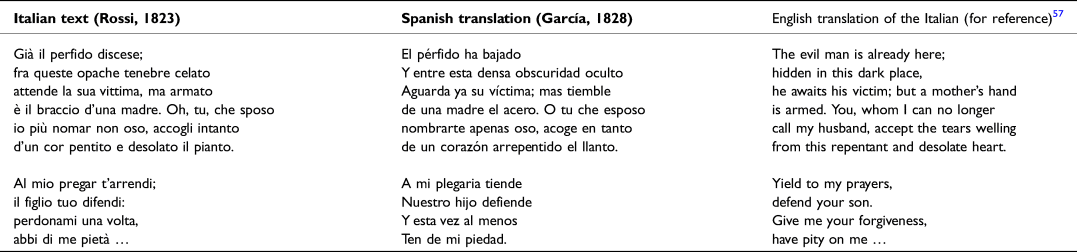

García's translation aimed not only to help creoles understand Rossi's libretto but also to fit the prosody of the music that he had already composed. Having no time to adjust the music and almost no literary experience with Spanish, García avoided elaborate experiment or sophisticated adaptation: he opted instead for a faithful translation of the Italian version, relying as much as he could on the many similarities of sound and meaning between Italian and Spanish (Il suo core il palpitar / De su seno el palpitar; Amore mi animò / Amor me animó). The structure of octosyllabic verses with the accent on the seventh syllable remained unchanged throughout the entire aria, and so did the rhyme scheme. Likewise, the cabaletta maintained the hexasyllable and its rhymes (quel dì / cangiò – allí / cambió; rapì / avvampò – rendí / ardió), except for the final verses, where García changed the meaning and order of the words to preserve the prosody of the music and the tension towards the final syllable (sapró / no, no) for the cadenza. The effects of the translation on the dramaturgy can be better explored in Semiramide's Act II aria ‘Al mio pregar t'arrendi’, where the pathos and theatrical tension posed greater difficulties for García (Table 3).Footnote 56

Table 3. Italian text with García's Spanish translation for Semiramide's aria from Semiramide (Act II scene 3)

In the recitative, Semiramide prays at Nino's grave and beseeches the protection of her late husband, whom she has killed. In the aria she addresses Arsace, her son, asking for his forgiveness and compassion for the murder. While Rossi's libretto seems to portray Semiramide as a queen who is overwhelmed by her sense of guilt and is no longer able to call Nino her husband after the murder, García's translation instead presents her as a wife who still dares (just) to do so (‘esposo nombrarte apenas oso’: I can barely call you husband). The reasons behind this change of meaning are at root prosodic: this turn of phrase allows García to preserve the metrical structure of the verse as well as the final ‘oso’ (I dare), which sounds and means the same in both languages. By the same token, in the first two verses of the aria the verb ‘tiende’ (to reach) translates the word ‘arrendi’ (to surrender), but only homophonically: the meaning of the two words is radically different. In this way, García tempers Semiramide's legendary rage with feelings of pity and commiseration. Her authoritarian words, presented by Rossi as weapons to defeat Nino's resentment, here in the Spanish translation turn into a more benevolent prayer – ‘a mi plegaria tiende, nuestro hijo defiende’ – aimed at drawing Nino near to her and her maternal intentions. Furthermore, the choice to introduce Arsace as ‘our’ (nuestro) son and not ‘your’ (tuo) goes in the same direction. Rossi's decision to emphasise Nino's paternity reminds the audience of Arsace's true identity and enhances the strong relationship between father and son as preparation for the final verses ‘Padre mio, ecco la tua vendetta’. García, in contrast, rejects these nuances and emphasises the familiar triangle between Nino, Ninia and Semiramide. In doing so, although he alters the dramatic forces of the scene, García preserves the length of the seven-syllable verse, the rhyme of the previous line, and assonance with the Italian verb ‘difendi’ upon which he had previously composed the music.

The reception of Semiramide

The day after the premiere, El sol, the conservative paper that had previously taken García's side on more than one occasion, ignored his new opera. The liberal paper El correo de la federación mexicana, by contrast, published the following report:

Last night, we attended a performance of the opera Semiramís in three acts, previously announced in two. We are sorry to say that the ability of García as a composer lags far behind that of his voice … Until a quarter to midnight, the audience endured monotonous music, annoying recitatives, especially in the first two acts, for the third one had a couple of duets which compensated for the boredom of the previous ones. The last aria with chorus of Mr García is excellent, although it does not seem to suit his voice. It might be too onerous for him. In a nutshell, the audience missed the sublime moments of Rosini [sic] that spontaneously move and stimulate the emotions of the listener. We can say that Semiramís cannot be performed at all unless with the experienced voices of García, Santa-Marta and Briones, although we believe they did not sing in their natural range. The role of Martínez is unbearable, while those of Castillo and Amada Plata are weak. The stage was brilliant, not only for the new and highly valuable decorations, but also for the costumes of the actors onstage and for the preparation of the movements.

The reporter, presumably an anonymous opera-goer of Mexico City, describes the performance with ambivalent words. In general, the music was probably below the expectation of the audience: with the exception of Idreno's ‘La speranza più soave’ and a few other scenes in the final act, Mexicans struggled to recognise the melodies of their idol Rossini in the new opera. When it comes to matters of vocality, the report becomes even more ambiguous, shifting continuously and clumsily between praise and reprimand for the performers, as if searching for impartiality towards a company (and an impresario and star performer) for which, as a liberal newspaper, El correo had never previously felt sympathy. The staging of the opera was, on the other hand, praised without hesitation for the ‘new and highly valuable decorations’. In other words, at least the efforts of García and Waldeck regarding the staging of Semiramís had paid off. García's decision to translate the libretto was also apparently much appreciated since, after the heated debates over Il barbiere and L'Abufar, this escaped all mention. In the end, however, Semiramís struggled to achieve the success both García and the elites expected. During the following months, García's opera was staged once in the summer and once on 11 September 1828, after which it disappeared forever.

Italian opera and Mexican postcoloniality

Unlike other musical genres after independence, opera remained central to the life of Mexico City's urban community and was continuously constructed ‘in exchanges between political and cultural actors’, as Axel Körner and Paulo Kühl remind us.Footnote 58 It intersected with creoles’ everyday life as a key cultural and political tool in the task of nation building, in opposition to a colonial past that, as argued by Nancy Vogeley, had always regarded foreign opera with suspicion.Footnote 59 By 1828, seven years after independence, importing Italian operas had already become a widespread and comfortable habitus for creole societies, supported by a solid managerial structure and Atlantic networks spanning from Livorno to Havana, and from New York to Bordeaux. This consolidated practice guaranteed a high-level artistic product ready to be performed while enabling outward-facing debates that only rarely involved self-critique: the clash between creole and European notions of operatic italianità triggered debates where, in fact, Mexican audiences did little but question the practice of others. The talks about Rossini's Tancredi and the premiere of Il barbiere were a prime example of this: How could a female singer perform a male role? How could an opera based on a Spanish plot be sung in Italian? Being imported and not produced locally, Italian operas could therefore be easily criticised, transformed, re-adapted and transcribed without ever calling into question the cultural references and tastes of the local population.

In their minds, the creation of operas seemed to be an even more effective practice to foster their own sense of proximity to the great capitals of the Old World and enable more effective narratives of comparison. However, as soon as García premiered his works, the creation of new operas revealed a short circuit with deeper and more unpredictable effects: instead of pushing Mexico towards the venerated model of Paris and London, it instead demonstrated, to recall the words of the historian Jeremy Adelman, the ‘stamina of colonialism’.Footnote 60 García's operas became discussed, transformed and reinterpreted in a hybrid narrative space where colonial experiences and new European dreams overlapped, revealing the contradictory impulses and reference points of creole society at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Composing Italian opera was one of the most complex cultural processes put in place by postcolonial Latin American republics in pursuit of national stability and international recognition. It questioned their notions of self-legitimation as cosmopolitan nations, as suggested by Thomas Turino, and brought into view what was otherwise hidden beneath the new carpet of postcolonial narratives.Footnote 61 The complex circumstances that led to the premiere of Semiramís showed the extent to which, as Walter Mignolo reminds us, creoles imagined themselves as fully European not only for the architectural styles of their buildings or their social practices, but also for the operas they were able to produce.Footnote 62

The premiere of García's opera disclosed an unexpected and unsettling scenario that questioned creoles’ self-perception precisely through their favourite European models. After three centuries of Spanish colonialism, creole elites had loaded their idea of Europe (excluding the Iberian Peninsula) with illusions, hopes and needs which resulted in an image that, not unlike the scenario described by Hamid Dabashi in relation to the Eastern world, had ‘nothing to do with the reality of Europe’.Footnote 63 It was only when, in the late 1810s, Spain withdrew from Latin America and creoles developed more straightforward contact with Europe, that Mexico found itself burdened by its own colonial past, becoming traumatically aware of its geographical and cultural distance from Europe.

Created and received in this context, García's Semiramide raised questions and problems that confronted Mexican opera-goers with a multifaceted idea of operatic italianità. Far from being a reassuring and predictable vessel of new values, Semiramide absorbed and reflected at the same time the manifold contradictions of Mexico's troubled nation building. Instead of embodying the ultimate step of Mexican Europeanisation, as most of the creoles were hoping, its premiere became a place of interaction, display and amplification of the manifold forces underpinning Mexico's postcolonial transition. In sum, García's opera became the ultimate and most tangible result of overlapping dynamics from the past and the present. It embodied, perhaps more than any other cultural product of the time, the struggle to construct and represent a new cultural identity from the ashes of colonialism – an identity that the new nations wanted to be recognisably European, but which was already and irretrievably creole.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the generous support of Benjamin Walton, Emilio Sala, Charlotte Bentley, Francesca Vella and Alexandra Leonzini. I also want to thank the anonymous readers of this article for their feedback. This research was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in the United Kingdom.