The paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS) is a novel disease entity first reported in late April, 2020. Reference Whittaker, Bamford and Kenny1 The first cluster of children presenting with this multi-system inflammatory condition emerged a few months after the first Covid-19 wave and temporal association to Covid-19 became apparent with every additional case reported. Clinical presentation is heterogeneous and shows similarity with other disease entities such as toxic shock syndrome or Kawasaki-disease, Reference Whittaker, Bamford and Kenny1,Reference Feldstein, Rose and Horwitz2 while its pathophysiology remains largely unknown to date. Reference Gruber, Patel and Trachtman3

The current most widely accepted hypothesis is that SARS-CoV-2-specific superantigen presentation to autoreactive T cells in combination with cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies and an unbalanced cytokine responses is the fundamental of PIMS in genetically predisposed children. Reference Lee, Day-Lewis and Henderson4–Reference Jiang, Tang and Levin6

No regional variations in clinical presentation and incidence have been reported so far. In the United States of America, the estimated incidence is around 316 in 100,000 in SARS-CoV-2-positive paediatric patients, Reference Payne, Gilani and Godfred-Cato7 a first estimation from an open German survey estimates the overall PIMS-TS rate as 1 per 4000 SARS-CoV-2 infections in children below 18 years of age. Reference Sorg, Hufnagel and Doenhardt8

Whereas only 20 to 40% of affected children show signs of active virus replication in form of a positive (RT) PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in the nasopharyngeal swab, almost all children are positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Reference Jiang, Tang and Levin6

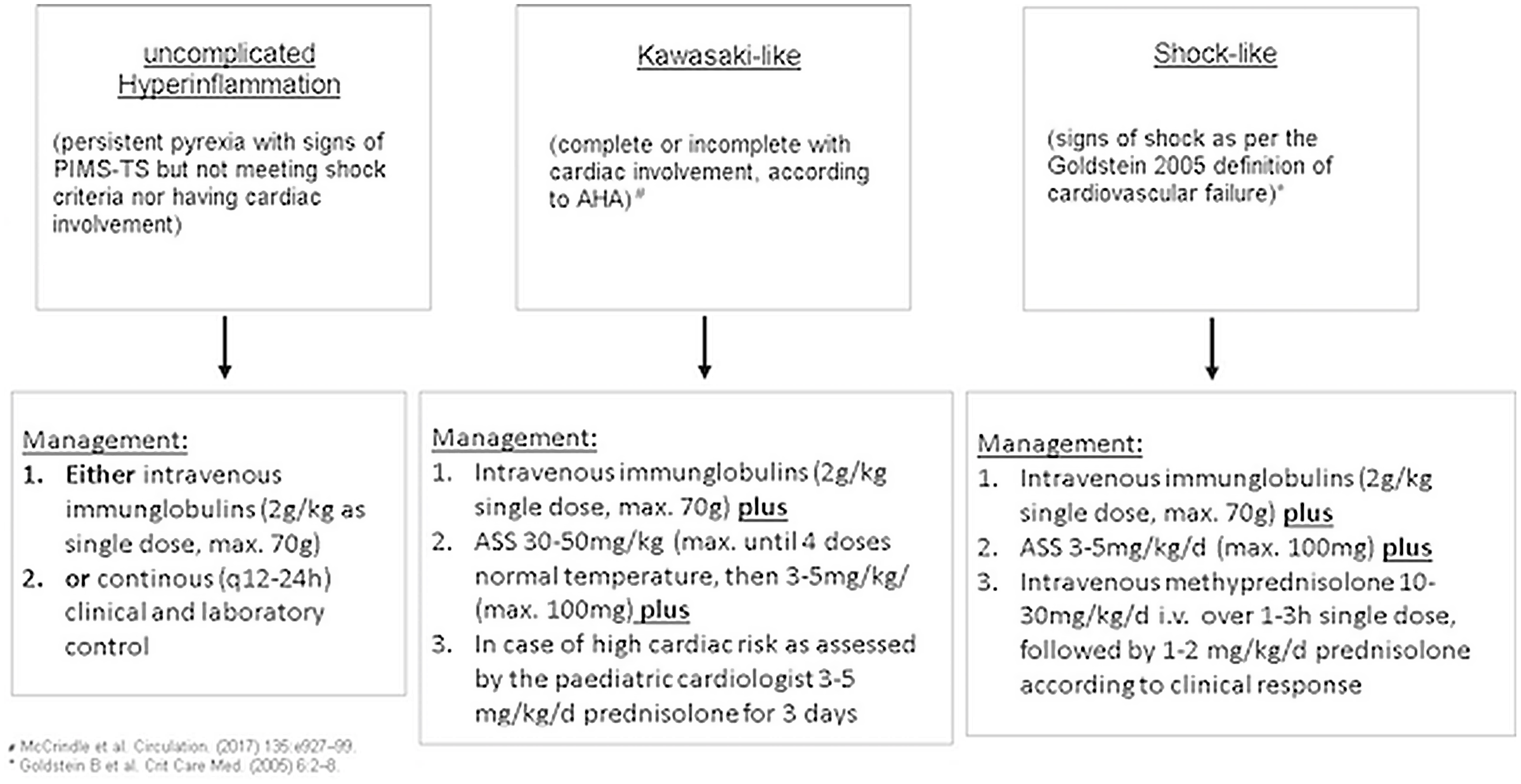

At the beginning of this year, Switzerland published a best practise recommendation and the UK national consensus on the management PIMS-TS discriminating between hyperinflammation, Kawasaki-like, and shock-like presentation. Reference Schlapbach, Andre and Grazioli9,Reference Harwood, Allin and Jones10 We have used these guidelines ever since to standardise diagnosis of PIMS-TS, patient classification, and therapy. Nevertheless, at present in the absence of randomised trials, there are still substantial uncertainties regarding clinical phenotypes, long-term outcomes, and optimal management.

Thus, we aimed to retrospectively evaluate the practicabilitiy and usefulness of the proposed guidelines from our local single-centre experience in a high volume German Childrens’ hospital.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of all inpatients treated in the Childrens’ hospital Kassel was carried out based on the ICD code U10.9 for the period from the 1st of February to the 30th of November, 2021. During this period, all patients have been treated according to an internal standard operating procedure based on the Swiss and UK recommendation and categorised as uncomplicated hyperinflammation, Kawasaki-like, or shock-like PIMS-TS with a standardised work-up (Table 1).

Table 1. Diagnostic work-up

ECGs were reported contemporaneously and reanalyzed by a single author (M.S., > 15 years clinical practice in paediatric cardiology). All echocardiograms were performed on Vivid S60 GE system, interpreted by the operator, and re-analyzed independently by one author (M.S.). Any discrepancies between the initial reports and reanalysis of ECGs and echocardiograms were reviewed independently by the second author (A.J.).

Global left ventricular systolic function was assessed with linear and 2D methods and left ventricular ejection fraction was based on biplane modified Simpson’s method and categorised as either normal (≥ 55%), or mild (45–54%), moderate (30–44%), or severe impairment (< 30%). Reference Lang, Badano and Mor-Avi11

PIMS-TS was defined as persistent high grade fever with typical clinical presentation including single or multi-organ dysfunction, CRP > 100 mg/L and one of the following: ferritine > 500 µg/l, thrombocytes < 150/nl, lymphocytes < 1.0/nl, or hypoalbuminemia.

According to clinical data, the patients were categorised in three groups and received standardised therapy accordingly (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Therapeutic algorythm.

Moreover, laboratory data for troponin was reviewed for patients with classic Kawasaki disease treated within the last 5 years.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Witten/Herdecke. The evaluation was carried out using SPSS Statistics Version 25.0. The data are presented as median with interquartile ranges. Data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test according to normality assumptions on univariate analysis followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Between February and November, 2021, 11 patients were discharged with the diagnosis of PIMS-TS. According to the regional incidence in the federal state of Hessen (as provided by the Robert-Koch-Institute), an estimate of about 1200 children between the age of 4 and 15 years had a Covid-19 wildtype infection between January and October, 2021 within the catchment of the Childrens’ Hospital Kassel. Reference Institut12 The regional risk for the development of PIMS in this age group was ∼0.92 in 1000.

The medium age of the patients was 7.5 years (IQR 4.3–12.5), female-to-male ratio was 2.1:1. Four patients (36%) were categorised as uncomplicated hyperinflammation, 4 (36%) as Kawasaki-like and 3 (27%) as shock-like. Childern categorised as Kawasaki-like tended to be younger compared to children with uncomplicated hyperinflammation or shock-like presentation (Table 2). A clear differentiation between the three groups upon clinical examination was not possible. However, terminal ileitis was exclusively found in patients with shock-like presentation (Table 2). All patients showed some kind of cardiac involvement, i.e., ECG changes as seen in peri- or perimyocarditis. However, an impaired left ventricular function was most commonly found in patients categorised as Kawasaki-like, the most severe impairment in one girl with shock-like presentation. Interestingly, none of the patients in the Kawasaki-like group had cervical lymphadenopathy (Table 2). All patients were positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and none had active SARS-CoV-2 replication defined as positive nasopharyngeal PCR.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics

All patients received therapy based on the internal standardised operating procedure (Fig. 1) and all patients were discharged in good clinical condition. Median length of hospital stay was 7 days (IQR 6.8–10.3). In all cases, specific therapy was initiated within 30 h after admission.

In the uncomplicated hyperinflammation group, one patient received intravenous immunoglobulins and prednisolone followed by aspirin (ASS), one patient was treated with ASS alone and in two patients inflammation subsided after 3 and 4 days, respectively, without any further therapy.

In the Kawasaki-like group, all patients received intravenous immunoglobulins, two received additional prednisolone, and all were discharged with ASS.

In the shock-like group, all patients received intravenous immunoglobulins and methylprednisolone therapy, but only two patients received additional ASS. All patients received fluid resuscitation and in two of the three cases catecholamine therapy was necessary to stabilise the cardiac function and circulation.

Inflammatory markers on admission were high in all groups, but significantly lower in patients with Kawasaki-like presentation. Significant differences were also noted for PCT which was highest in patients with shock-like presentation followed by hyperinflammtion and Kawasaki-like presentation (Table 3). With respect to parameters for cardiac function and circulation, differences in BNP, troponin, and base excess were significantly different between the groups. Whereas BNP was highest in patients with shock-like presentation, Troponin was highest in the Kawasaki-like group (Table 3). Of note, troponin was not increased in any of the 28 patients treated for classic Kawasaki disease within the last 5 years as reviewed from the hospital laboratory database. Overall, shock-like presentation appears to be characterised by the highest level of inflammation (CRP and PCT) and signs of circulatory dysfunction (BE and BNP). In Kawasaki-like disease, in contrast, cardiac dysfunction – as reflected by high troponin – stands out as the main pathogenetic factor whereas systemic inflammation was much less pronounced (Table 3).

Table 3. Laboratory parameters 24 h upon admission (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction)

* Two missing values.

Discussion

In this study, all three aspects, i.e. the incidence of PIMS-TS with ∼0.92 per 1000 children with Covid-19 infection, the clinical presentation and the age distribution were within the same range as in previous reports, Reference Flood, Shingleton and Bennett13,Reference Godfred-Cato, Bryant and Leung14 with the exception of coronary artery abnormalities which were very uncommon in our cohort in contrast to previous studies. Reference Ramcharan, Nolan and Lai15 One possible explanation could be that all patients with Kawasaki- or shock-like presentation in this study were treated for PIMS within 30 h after admission.

According to the Swiss best practise recommendation Reference Schlapbach, Andre and Grazioli9 and the UK national consensus on the management Reference Harwood, Allin and Jones10 of PIMS-TS, about one-third of the patients presented with uncomplicated hyperinflammtion, Kawasaki-like and shock-like disease. Diagnostic work-up and therapy as proposed by both guidelines proved suitable in this real-life hospital setting and allowed fast catergorisation and initiation of adequate therapy with an overall good clinical outcome. Interestingly, we observed specific laboratory pattern discriminating the three proposed subforms of PIMS. Uncomplicated hyperinflammation seems to be characterised by high CRP and moderate PCT, but relatively low BNP levels; shock-like presentation by high CRP, high PCT, and high BNP levels, whereas Kawasaki-like presentation had relatively low CRP and BNP levels compared to the others groups, but substantially higher troponin levels, probably reflecting primary cardiac involvement. Early anaylsis of PCT, BNP, and troponin in the emergency room might thus be a valuable tool to early catergorise the patient and initiate a specific therapy; moreover, simple markers as blood sedimentation rate – which was not part of the standardised operating procedure in this study – might be useful to discriminate high inflammation activity as early as possible. Additionally, increased troponin levels may be used to discriminate classic Kawasaki syndrome from Kawasaki-like PIMS-TS. However, the case number in this study as well as the retrospective design does not allow any final conclusion. Further prospective studies with the markers mentioned above including blood sedimentation rate would be of great value in the understanding and for the best treatment of children and adolescents with PIMS-TS.

Based on our experience, we recommend cardiology follow-up for the shock and Kawasaki-like PIMS patients 2–4 weeks after discharge from hospital, depending on residual ECG, echo, and clinical findings.

During the first and second wave, the incidence of Covid-19 in the age group below 14 years was substantially lower compared to all others age groups in Germany ranging between 10 and 100/100,000. Reference Institut12 Only with the third wave, infections rates reached the same level as in other age groups. It is thus not surprising that the number of PIMS cases admitted to the Childrens’ Hospital Kassel rose quite substantially over the last 6 months considering the observation that most cases of PIMS occur 4–6 weeks after the Covid-19 infection. Reference Feldstein, Rose and Horwitz2,Reference Belot, Antona and Renolleau16 Germanwide, the national PIMS survey has recorded 477 cases between May, 2020 and November, 2021. 17 Importantly, with the forth wave now having the highest incidences (>1000/100,000) in the age group of 0–14 years children Reference Institut12 it is reasonable to assume that we will see an increase in the number of PIMS-TS by the beginning of 2022.

Overall, despite the single-centre, retrospective design of this study, we can demonstrate the practicability of the Swiss best practise recommendation Reference Schlapbach, Andre and Grazioli9 and the UK national consensus on the management Reference Harwood, Allin and Jones10 of PIMS-TS in a high-volume childrens’ hospital in Germany. Both guidelines allow fast categorisation and initiation of specific therapy and might thus improve the outcome of the patients. Implementation of local standardised operating procedures for PIMS-TS – e.g., as presented here for the Kassel standardised operating procedure and modified based on the international recommendations mentioned above – is highly warranted considering the probabililty of rising numbers of PIMS-TS cases after the fourth wave of Covid-19 infection. Still, more studies are needed to further specify the exact differences between the three proposed types of PIMS-TS.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.