INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in both females and males worldwide. HPV types 6 and 11 cause anogenital warts, and most notably types 16 and 18 cause anogenital malignancies. In women, cervical cancer is the most common of these malignancies (15/100 000 women) [Reference Ferlay1] while anal cancer is relatively rare. However, anal cancer is much more common in men who have sex with men (MSM), especially in MSM with HIV who have a high incidence rate of anal cancer (46/100 000 person-years) [Reference Machalek2].

Studies in Australia observed a rapid fall in genital warts in young females by more than 90% within 4 years of the introduction of quadrivalent (types 6, 11, 16, 18) HPV vaccine for females aged between 12 and 27 years in July 2007, including a large herd immunity effect in heterosexual men who had not received the vaccine [Reference Ali3, Reference Read4]. This marked reduction in genital warts in heterosexuals occurred with a vaccine coverage of about 70%, suggesting that this level is sufficient to see the elimination of genital warts. Not surprisingly, no reductions in genital warts were observed in MSM. Studies monitoring the effect of HPV vaccines have used genital warts as a marker of their effect because high-risk HPV types are largely asymptomatic until the development of malignancy many years later [Reference Ali3–Reference Tabrizi5], but by contrast genital warts appear shortly after infection and provide an effective marker of incident HPV-6 and -11 infections.

In February 2013, Australia introduced the HPV vaccine for boys aged 12–15 years because mathematical models had suggested that there was an additional benefit to women and a direct benefit to men from including boys in the vaccination schedule [Reference Georgousakis6]. However, it is not clear how effective the vaccine will be in controlling HPV in MSM and what proportion need to be vaccinated to achieve the same reduction that has been observed in heterosexuals. There has been very little research on transmission probabilities of HPV between different sites in MSM, and understanding this would facilitate the development of these models. One method of improving our understanding of HPV transmission between different anatomical sites would be to study the proportion of new clients with genital warts at different anatomical sites in heterosexuals compared to MSM. The aim of this study is to describe the ratio of anogenital warts between different anatomical sites in men and women in order to infer the required vaccine coverage in MSM through mathematical models in future studies.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis investigating all new patients attending the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC) in Victoria, Australia between 1 February 2002 and 31 December 2013. MSHC is the major and largest public sexual health clinic serving the city of Melbourne (~3·5 million people) in Victoria, Australia. MSHC is located in the city of Melbourne and provides a walk-in service with no referrals being required. The clinic provides about 35 000 clinical consultations annually and all services are free-of-charge. All new patients attending MSHC for the first time were included in this study. Patients were categorized as heterosexual male, female, and MSM based on their self-reported sexual behaviours. Heterosexual males were defined as men who did not have sex with a man or had sex with a female in the past 12 months; while heterosexual females were defined as women who have had male partners. Men reporting any sexual contact with another man in the past 12 months or in the 12 months before any previous visit to MSHC were defined as MSM.

Since heterosexual men can also benefit from herd immunity of the female HPV vaccination programme, both heterosexual male and female patients attending MSHC after 1 January 2008 were excluded from the analysis. MSM attending MSHC prior to 2008 were excluded in this analysis because the site of diagnosed genital warts (anal and penile) was not recorded in the database. Demographic characteristics, sexual behavioural data, and clinical diagnoses of each new patient were extracted from the Clinic Practice Management System (CPMS) and entered into an Excel spreadsheet (version 2010, Microsoft Corp., USA).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software v. 21 (SPSS Inc., USA). Total numbers of patients diagnosed with genital wart at each anatomical site (anal, penile, vulval) were tabulated according to their sexual orientation. Median and interquartile range (IQR) of age and number of sex partners in the past 12 months were also calculated. The ratios for penile-to-anal warts in MSM and penile-to-vulval warts in heterosexual individuals were calculated.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia (number 83/14).

RESULTS

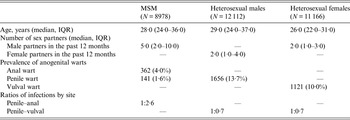

A total of 32 256 new patients were included in this study, with 8978 MSM, 12 112 heterosexual males and 11 166 heterosexual females (Table 1). The median age was 28·0 years (IQR 24·0–36·0) in MSM, 29·0 years (IQR 24·0–37·0) in heterosexual males, and 26·0 years (IQR 22·0–31·0) in heterosexual females. The median of male sex partners in MSM was 5·0 (IQR 2·0–10·0) in the past 12 months, and the numbers of sex partners in both heterosexual males and females in the past 12 months were similar (median 2·0).

Table 1. Number and percentage of new patients diagnosed as having genital warts at the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre

MSM, Men who have sex with men; IQR, interquartile range.

Out of 8978 MSM, 362 (4·0%) had anal warts, 141 (1·6%) had penile warts but only 11 (0·1%) had warts at both sites. The penile-to-anal wart ratio was about 1:2·6. About 13·7% (1656/12 112) of the heterosexual males were diagnosed with penile warts, which was slightly higher than the prevalence of genital warts in heterosexual females (10·0%, 1121/11 166). This gave a penile-to-vulval wart ratio of about 1:0·7.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that proportion of heterosexual males with penile warts was similar to the proportion of females with vulval warts, and both groups had a similar number of sexual partners in the past 12 months. However, MSM are 2·6 times more likely to have anal warts than penile warts, which is consistent with findings from previous studies showing anal warts occurred more commonly than penile warts in MSM [Reference Jin7, Reference Zou8]. If one assumes that the majority of anal warts in MSM come from exposure to penile warts (via HPV-6 or -11) then it is likely that the anal epithelium may be more susceptible to HPV infection than the female genital epithelium. If this is so, it has substantial implications for the control of HPV in MSM, because mathematical models in MSM would need to include the rate of partner change, the duration of site-specific HPV infection and transmissibility between different sites to calculate the reproductive rate. The reproductive rate is an important indicator to determine the coverage of vaccination required to reduce infections.

Our study has several limitations that are important to consider in interpreting the results. First, our data are based on a single urban sexual health clinic and the findings may be different in other settings. Second, our findings assumed that men and women had equal sexual risk in the last 12 months and this was why the ratio of warts was equal between them. Given that most warts develop within 12 months [Reference Winer9], the numbers of opposite-sex and sexual partners were very similar, and this is likely to be the case. Furthermore, national surveillance data in the UK show a similar number of genital warts in heterosexual men and women [10]. Third, we have assumed that most anal warts in MSM have occurred from penile–anal sex. This seems reasonable but other anal activities such as anal fingering do occur and HPV has been found on fingernails, so this cannot be excluded, although hand–penile contact is also almost universal with sexual activity [Reference Phang11], and therefore one would expect this to also transmit warts. Fourth, the ratios are of proportions of new patients diagnosed with warts so our findings therefore rely on assuming that men and women are equally likely to attend the clinic for reasons other than warts and that MSM are equally likely to have insertive and receptive anal sex. Fifth, a previous study showed that a substantial proportion (~20%) of Australian women reported ever having anal sex [Reference Fethers12]. Given these are clinic-based data and the conventional medical practices, we have assumed all heterosexual individuals attending MSHC did not have anal sex and hence we are not able to calculate the ratio of penile-to-anal sex in heterosexual individuals. Sixth, we have neglected pharyngeal infections through oral sex. Although oral sex (~97%) is more common than anal sex (~86%) in Australian MSM, it has been reported that HPV infection through oral sex is rare (2·0%) compared to penile (9·5%) and anal canal (30·8%) [Reference Zou8]. In addition, oral sex (70·6%) is as common as penile–vaginal sex (69·3%) in heterosexual women [Reference Fethers12]. Oral–vaginal or oral–anal exposure in heterosexuals might be possible for wart transmission but oral wart virus (HPV types 6 and 11) is rare in heterosexual populations [Reference Antonsson13]. Seventh, we have assumed that all warts in MSM are acquired through male-to-male sexual contact but a small proportion of Australian MSM (~6·7%) might also have sex with females [Reference Lyons14]. Finally, for practical reasons we studied two different periods for heterosexuals (pre-2007) and MSM (post-2008), but given that MSM have had no change in warts since 2008 this seems reasonable.

There has been a 92·6% decline of genital wart diagnoses in women aged <21 years from the implementation of the female HPV vaccination programme in 2007 until 2011 [Reference Ali3]. A similar level of reduction (81·8%) in genital warts has also been observed in heterosexual males aged <21 years (from 12·1% in 2007 to 2·2% in 2011) [Reference Ali3], which suggests that heterosexual males have benefited from a protective effect (i.e. herd immunity) from the female HPV vaccination programme [Reference Garnett15]. Currently, only 70% of young women have received full coverage by the HPV vaccination programme [Reference Brotherton16]. Vaccinating heterosexual males will also provide a similar level of herd immunity to unvaccinated females [Reference Clemens, Shin and Ali17]. An Australia-based model estimated that a further 24% of new HPV infections would be prevented by 2050 if a similar proportion (71–78%) of young heterosexual males were vaccinated [Reference Georgousakis6]. Unlike heterosexual males, there have been no reductions observed in genital warts in MSM following the female HPV vaccination programme [Reference Ali3, Reference Read4]. Given that the female quadrivalent vaccine has demonstrated a significant reduction in genital warts in women and heterosexual males and in high-grade squamous lesions [Reference Read4, Reference Tabrizi5], a similar reduction would be expected in MSM after the introduction of male HPV vaccination in 2013 if the reproductive rate was the same. However, the reproductive rate for HPV in MSM is not known and therefore it is a challenge to estimate the optimal vaccine coverage and further mathematical models are required in the field. The reproductive rate is likely to be higher on the basis of sexual practices with only one-third of MSM reported having a monogamous relationship with a male partner and a high rate of partner change [Reference Lee18]. Apart from the male universal HPV vaccination programme, it is suggested that MSM should also be vaccinated against HPV to reduce the incidence of anal cancer [Reference Lawton, Nathan and Asboe19].

Currently, there are no MSM-specific models and no guidance available on what proportion of MSM need to receive the HPV vaccine to achieve the same reductions in genital warts that have been observed in heterosexuals. This study describes the ratio of genital warts by anatomical site, which is one of the key parameters used in predictive mathematical models to inform the HPV vaccine coverage that is required to achieve optimal reductions in anal cancer and anogenital warts, and to forecast the future epidemics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge A. Afrizal for his assistance with data extraction. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) programme grant (grant no. 568971).

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.