Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV), which encompasses physical, sexual and emotional violence perpetrated by an intimate partner or ex-partner, has been recognised as a pervasive public health problem (World Health Organization, 2018). Globally, nearly 30% of women aged 15 years and older have been exposed to IPV (World Health Organization, 2018). Mounting research has shown the detrimental consequences of IPV on victims’ health and well-being, in particular depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Lagdon et al., Reference Lagdon, Armour and Stringer2014; Bacchus et al., Reference Bacchus, Ranganathan, Watts and Devries2019).

The growing field of biological markers such as telomere length (TL) has opened a unique avenue for understanding the biological mechanisms underpinning diseases (Ridout et al., Reference Ridout, Levandowski, Ridout, Gantz, Goonan, Palermo, Price and Tyrka2018). Telomeres are nucleon–protein complexes at the end of the eukaryotic chromosomes. The DNA component, comprising (TTAGGG)n, is a biomarker of ageing and adverse health outcomes that shortens in somatic cells as they replicate (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Epel and Lin2015; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhan, Pedersen, Fang and Hagg2018). Multiple Mendelian randomisation studies have shown the potential causal effect of telomere shortening and a number of health outcomes, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease (Haycock et al., Reference Haycock, Burgess, Nounu, Zheng, Okoli, Bowden, Wade, Timpson, Evans, Willeit, Aviv, Gaunt, Hemani, Mangino, Ellis, Kurian, Pooley, Eeles, Lee, Fang, Chen, Law, Bowdler, Iles, Yang, Worrall, Markus, Hung, Amos, Spurdle, Thompson, O'Mara, Wolpin, Amundadottir, Stolzenberg-Solomon, Trichopoulou, Onland-Moret, Lund, Duell, Canzian, Severi, Overvad, Gunter, Tumino, Svenson, van Rij, Baas, Bown, Samani, van t'Hof, Tromp, Jones, Kuivaniemi, Elmore, Johansson, McKay, Scelo, Carreras-Torres, Gaborieau, Brennan, Bracci, Neale, Olson, Gallinger, Li, Petersen, Risch, Klein, Han, Abnet, Freedman, Taylor, Maris, Aben, Kiemeney, Vermeulen, Wiencke, Walsh, Wrensch, Rice, Turnbull, Litchfield, Paternoster, Standl, Abecasis, SanGiovanni, Li, Mijatovic, Sapkota, Low, Zondervan, Montgomery, Nyholt, van Heel, Hunt, Arking, Ashar, Sotoodehnia, Woo, Rosand, Comeau, Brown, Silverman, Hokanson, Cho, Hui, Ferreira, Thompson, Morrison, Felix, Smith, Christiano, Petukhova, Betz, Fan, Zhang, Zhu, Langefeld, Thompson, Wang, Lin, Schwartz, Fingerlin, Rotter, Cotch, Jensen, Munz, Dommisch, Schaefer, Han, Ollila, Hillary, Albagha, Ralston, Zeng, Zheng, Shu, Reis, Uebe, Huffmeier, Kawamura, Otowa, Sasaki, Hibberd, Davila, Xie, Siminovitch, Bei, Zeng, Forsti, Chen, Landi, Franke, Fischer, Ellinghaus, Flores, Noth, Ma, Foo, Liu, Kim, Cox, Delattre, Mirabeau, Skibola, Tang, Garcia-Barcelo, Chang, Su, Chang, Martin, Gordon, Wade, Lee, Kubo, Cha, Nakamura, Levy, Kimura, Hwang, Hunt, Spector, Soranzo, Manichaikul, Barr, Kahali, Speliotes, Yerges-Armstrong, Cheng, Jonas, Wong, Fogh, Lin, Powell, Rice, Relton, Martin and Davey Smith2017; Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Pilling, Kuchel, Ferrucci and Melzer2019). The existing literature on the relationship between traumatic events and TL has mainly focused on early life (Hanssen et al., Reference Hanssen, Schutte, Malouff and Epel2017; Ridout et al., Reference Ridout, Levandowski, Ridout, Gantz, Goonan, Palermo, Price and Tyrka2018). Studies among adults on the relationship between IPV and TL have produced inconsistent findings. For example, Humphreys et al. (Reference Humphreys, Epel, Cooper, Lin, Blackburn and Lee2012) found that TL was significantly shorter in 61 formerly abused women than in 41 controls. However, such an association was not found in another 30-year birth cohort study of 677 women (Jodczyk et al., Reference Jodczyk, Fergusson, Horwood, Pearson and Kennedy2014). Interindividual variation in TL at any given chronological age remains substantial and is often a complicating factor in such studies, as are exposome features (i.e. biotic and abiotic life course exposures) (Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, Painer, Natterson-Horowitz, Johnson, Miranda and Stenvinkel2021). Additionally, these studies did not specify the types of IPV and their separate and combined effects, nor consider mental health confounders. Thus, the mixed findings may be due to insufficient power or confounding. Research shows experiencing multiple forms of victimisation (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Chen and Chen2021), such as more than one type of IPV (Lagdon et al., Reference Lagdon, Armour and Stringer2014), can increase the severity of mental health outcomes, studies on TL require greater granularity in their measurement of the types and dosage of IPV.

Hence, this study aimed to examine the association between IPV types (physical, sexual, emotional) and TL in a sufficiently large sample size from the UK Biobank (UKB). This allows mental health symptoms and other covariates to be taken into consideration in the analyses. The large sample also enabled the relative importance of the multiple exposures to various types of IPV on TL to be compared.

Methods

Study design and participants

UK Biobank recruited more than 502 506 participants (aged 40–69 years) from the general population between 2006 and 2010. Participants were assessed at one of 22 assessment centres across England, Scotland and Wales. They completed a self-administered questionnaire and a face-to-face interview. The details of the study design and protocols of UK Biobank are provided elsewhere (Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh, Downey, Elliott, Green, Landray, Liu, Matthews, Ong, Pell, Silman, Young, Sprosen, Peakman and Collins2015). This is a retrospective cohort study consisting of the subsample of UK Biobank participants who completed a web-based mental health questionnaire, in which they reported any exposure to IPV since 16 years of age as well as symptoms of depression and PTSD. TL measurements were undertaken on the DNA of participants’ blood samples. UK Biobank received ethical approval from the North-West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (reference 11/NW/0382) and all participants provided written informed content.

Measures

Exposure: IPV

IPV was self-reported through an online questionnaire using a five-point Likert scale for each of three types of IPV (physical, emotional and sexual violence) that occurred since the age of 16 years. The items were adapted from the British Crime Survey (Khalifeh et al., Reference Khalifeh, Oram, Trevillion, Johnson and Howard2015). The threshold values on the Likert scale were used to define the presence (‘Sometimes’, ‘Often’, ‘Very often’) or absence (‘Never’ and ‘Rarely’) of each type of IPV. The categorisation is based on the assumption that people who reported ‘rarely’ did not have chronic, repeated exposure to violence. The exposure variable was the number of types of IPV, and was categorised as 0, 1, 2 and 3. Detailed descriptions of the variables are contained in Supplemental Table 1.

Outcome: leukocyte telomere length

Detailed information on the measurement of TL in UKB has been provided elsewhere (Codd et al., Reference Codd, Denniff, Swinfield, Warner, Papakonstantinou, Sheth, Nanus, Budgeon, Musicha, Bountziouka, Wang, Bramley, Allara, Kaptoge, Stoma, Jiang, Butterworth, Wood, Di Angelantonio, Thompson, Danesh, Nelson and Samani2022). Briefly, DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes. TL was assayed using the quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The assay results were presented as a relative ratio of the telomere repeat copy number (T) to a single-copy gene (S). The calculated T/S ratios were then adjusted for technical variation, log-transformed and Z-standardised to approximate a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and s.d. of 1. Over 23 000 measurements had undergone a reproducibility check which resulted in good coefficient of variation (median 5.53, interquartile range 2.67–9.68) (Codd et al., Reference Codd, Denniff, Swinfield, Warner, Papakonstantinou, Sheth, Nanus, Budgeon, Musicha, Bountziouka, Wang, Bramley, Allara, Kaptoge, Stoma, Jiang, Butterworth, Wood, Di Angelantonio, Thompson, Danesh, Nelson and Samani2022). Technicians who underwent the TL assessment had no access to the participants’ other data, including exposure to violence.

Other variables

The online questionnaire also measured current symptoms of depression and PTSD, using two well-established tools: the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and the Post-traumatic stress disorder Check List – civilian Short version (PCL-S). Specifically, PHQ-9 measures depression severity from the frequency of nine items, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). All items were summated to provide a total score of depression severity, with higher scores indicating more symptoms. Previous work has demonstrated the validity and reliability of using this scale in UK Biobank (Kandola et al., Reference Kandola, Osborn, Stubbs, Choi and Hayes2020). PCL-S consists of five items that map onto the DSM-IV criteria (Wilkins et al., Reference Wilkins, Lang and Norman2011).

Demographic information was collected, including sex, age, ethnicity, highest educational level and Townsend Deprivation Index; a composite area-based measure derived from unemployment, car ownership, household overcrowding and owner occupation, with higher scores indicating higher levels of deprivation (Elovainio et al., Reference Elovainio, Hakulinen, Pulkki-Råback, Virtanen, Josefsson, Jokela, Vahtera and Kivimäki2017; Howe et al., Reference Howe, Kanayalal, Harrison, Beaumont, Davies, Frayling, Davies, Hughes, Jones, Sassi, Wood and Tyrrell2020).

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were first computed to describe the participants’ characteristics, IPV experiences and mental health problems. A set of independent χ 2 tests were performed to compare the potential sex differences in categorised variables (ethnicity, education attainment, IPV types and numbers of IPV (i.e. 0, 1, 2 and 3)) and t-tests were performed to compare continuous variables (age, deprivation index, mental health symptoms and TL). We then used χ 2 and t-tests to compare the possible differences in demographic characteristics, mental health problems and TL by the number of IPV.

To explore the association between IPV and TL, we conducted multivariable linear regression models, adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics: age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation index and education. These covariates were adjusted because they are likely to be confounders, affecting the likelihood of IPV as well as TL. Both the types of IPV and the number of types were used as exposure variables. Symptoms of depression and PTSD were additionally adjusted in a separate sensitivity analysis. These are possible confounders (as depression and PTSD might affect the recall of IPV) or mediators (as IPV could increase the risk of depression and PTSD) which we do not have data in this study to ascertain. The sensitivity analysis would be subject to overadjustment bias if depression and PTSD are, in fact, mediators. Other chronic conditions were not adjusted in the analysis because they are less likely to affect the likelihood or the report of IPV. Finally, we investigated the potential interaction between demographic characteristics and IPV on TL. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2. p < 0.05 in two-sided tests was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 502 488 UK Biobank participants, 156 379 (31.1%) completed all the IPV-related questions. Of these, 8780 (5.6%) and 3550 (2.4%) were excluded due to no valid TL and covariate data, respectively. Therefore, the sample size was 144 049 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 1 shows the participants’ characteristics by sex. The mean age of the participants was 55.89 (s.d. 7.74) years, 56.25% were female and 16.16% reported experience of IPV. The most frequently reported type was emotional (14.16%), followed by physical (6.37%) and then sexual violence (2.52%). Overall, 10.68, 4.07 and 1.41% of participants reported one, two and three types, respectively. Compared with men, women reported significantly more IPV events across all three types of IPV.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics by sex

Note. LTL, leucocyte telomere length. LTL was expressed in T/S ratio here and in further analyses.

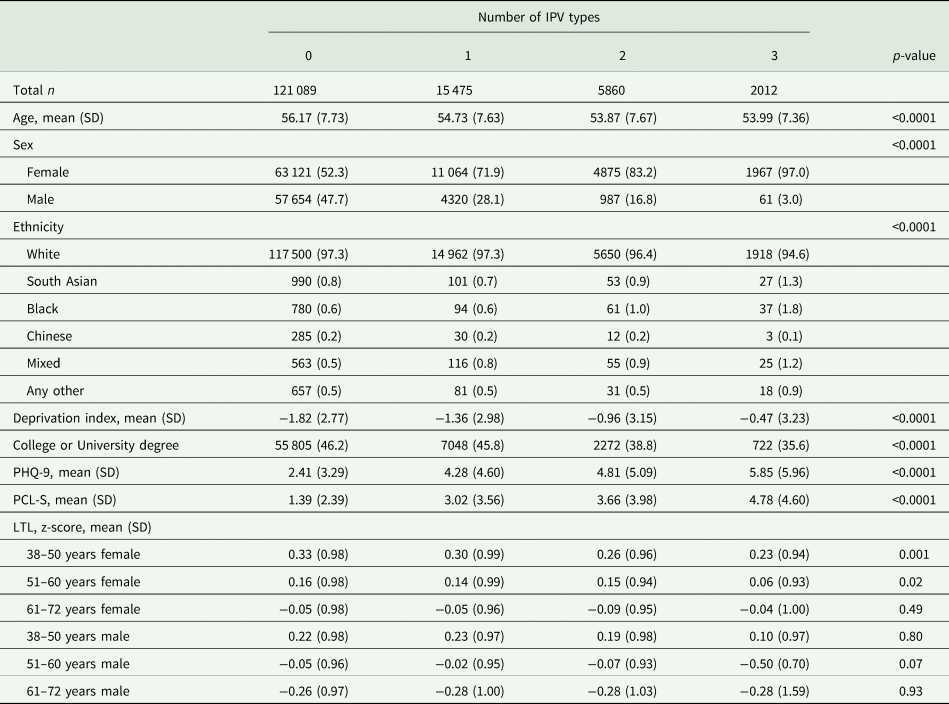

Table 2 shows differences in demographic characteristics, mental health problems and TL in multiple types of IPV (i.e. 0, 1, 2 and 3). Those who experienced more IPV types were younger, more likely to be female, South Asian, Black, or with mixed ethnicity, had lower highest education level and higher levels of deprivation. Exposure to higher numbers of IPV was also associated with higher levels of depression and PTSD.

Table 2. Participants’ characteristics by sex by number of IPV types

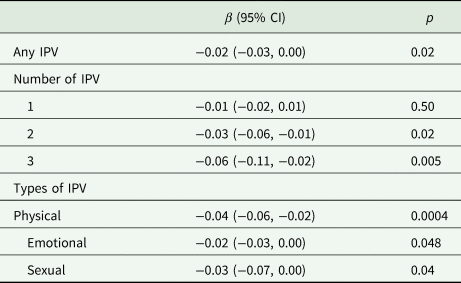

After adjusting for sociodemographic factors, any IPV was associated with 0.02-s.d. shorter TL (β = −0.02, 95% CI −0.04 to −0.01) (Fig. 1). Of the three types of IPV, physical violence had a marginally stronger association (β = −0.05, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.02) than the other two types. The associations of numbers of IPV and TL showed a dose–response pattern whereby those who experienced all three types of IPV types had the shortest TL (β = −0.07, 95% CI −0.12 to −0.03), followed by those who experienced two types (β = −0.04, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.01). Following additional adjustment for symptoms of depression and PTSD, the associations were slightly attenuated but the general trend by number of IPVs remained (Table 3).

Fig. 1. Association between IPV and telomere length.

Note. Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation and education.

Table 3. Association between IPV and standardised LTL

Note. Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, education and symptoms for depression and PTSD.

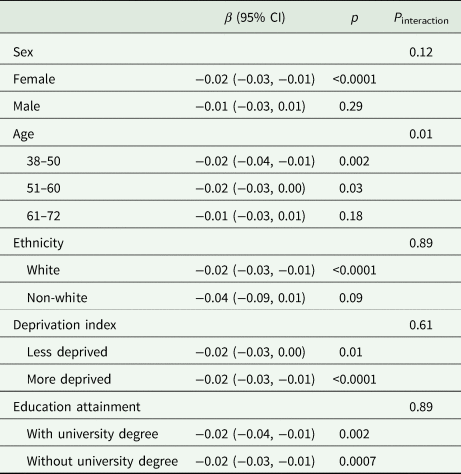

Table 4 shows the associations between IPV and TL by socio-demographic subgroups. The association was stronger among younger participants, particularly in the 38–60 years age group (P interaction = 0.01). No interactions reached statistical significance for other demographic characteristics.

Table 4. Association between IPV and standardised LTL by sociodemographic subgroups

Note. Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, education and symptoms for depression and PTSD.

Discussion

Main findings

This is among the first studies which clearly show that each type of IPV was associated with shorter TL and the association was the strongest among participants who experienced multiple types of IPV, albeit with a small effect size. The findings were consistent even when adjusted for symptoms of depression and PTSD, which could affect the recall of IPV or may be a mediator of the association between IPV and TL. Given that shorter TL is associated with various major illnesses, within the ‘diseasome of ageing’ (Shiels et al., Reference Shiels, McGuinness, Eriksson, Kooman and Stenvinkel2017, Reference Shiels, Painer, Natterson-Horowitz, Johnson, Miranda and Stenvinkel2021), including cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, cancer and Alzheimer's disease (Haycock et al., Reference Haycock, Burgess, Nounu, Zheng, Okoli, Bowden, Wade, Timpson, Evans, Willeit, Aviv, Gaunt, Hemani, Mangino, Ellis, Kurian, Pooley, Eeles, Lee, Fang, Chen, Law, Bowdler, Iles, Yang, Worrall, Markus, Hung, Amos, Spurdle, Thompson, O'Mara, Wolpin, Amundadottir, Stolzenberg-Solomon, Trichopoulou, Onland-Moret, Lund, Duell, Canzian, Severi, Overvad, Gunter, Tumino, Svenson, van Rij, Baas, Bown, Samani, van t'Hof, Tromp, Jones, Kuivaniemi, Elmore, Johansson, McKay, Scelo, Carreras-Torres, Gaborieau, Brennan, Bracci, Neale, Olson, Gallinger, Li, Petersen, Risch, Klein, Han, Abnet, Freedman, Taylor, Maris, Aben, Kiemeney, Vermeulen, Wiencke, Walsh, Wrensch, Rice, Turnbull, Litchfield, Paternoster, Standl, Abecasis, SanGiovanni, Li, Mijatovic, Sapkota, Low, Zondervan, Montgomery, Nyholt, van Heel, Hunt, Arking, Ashar, Sotoodehnia, Woo, Rosand, Comeau, Brown, Silverman, Hokanson, Cho, Hui, Ferreira, Thompson, Morrison, Felix, Smith, Christiano, Petukhova, Betz, Fan, Zhang, Zhu, Langefeld, Thompson, Wang, Lin, Schwartz, Fingerlin, Rotter, Cotch, Jensen, Munz, Dommisch, Schaefer, Han, Ollila, Hillary, Albagha, Ralston, Zeng, Zheng, Shu, Reis, Uebe, Huffmeier, Kawamura, Otowa, Sasaki, Hibberd, Davila, Xie, Siminovitch, Bei, Zeng, Forsti, Chen, Landi, Franke, Fischer, Ellinghaus, Flores, Noth, Ma, Foo, Liu, Kim, Cox, Delattre, Mirabeau, Skibola, Tang, Garcia-Barcelo, Chang, Su, Chang, Martin, Gordon, Wade, Lee, Kubo, Cha, Nakamura, Levy, Kimura, Hwang, Hunt, Spector, Soranzo, Manichaikul, Barr, Kahali, Speliotes, Yerges-Armstrong, Cheng, Jonas, Wong, Fogh, Lin, Powell, Rice, Relton, Martin and Davey Smith2017), TL could reflect a biological mechanism on the burden of physiological ‘wear and tear’. This suggests that the IPV could accelerate biological ageing, which predisposes to future adverse health outcomes.

Findings in the context of existing evidence

In this study, we found that women were more likely to report all three types of IPV. Previous research reported mixed findings on gender and IPV victimisation (Chan, Reference Chan2011), which may be related to gender-specific factors and cultural-specific gender roles (Chan, Reference Chan2011; Laskey et al., Reference Laskey, Bates and Taylor2019). The traditional gendered (or feminist) perspective suggests that the perpetrator of IPV is male and the victim is female (Martín-Fernández et al., Reference Martín-Fernández, Gracia and Lila2018). However, men's physio-psychological response to IPV may be similar to that of women. The gender differences in IPV prevalence observed in our study may result from different coping strategies (Laskey et al., Reference Laskey, Bates and Taylor2019), such that male victims are less likely to report even if they experience similar victimisation. Regardless, given the evidence on the association between IPV and TL both among the victims (as shown in this study) and among the offspring (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Lo, Ho, Leung, Yee and Ip2019), future studies should look into whether TL is a mechanistic factor leading to health outcomes, or whether TL can be a marker to help risk stratify IPV victims for health-related interventions.

We found the association between IPV and TL was stronger in younger participants. Two competing theories have addressed how the relationship might change with age. Cumulative disadvantage theory states that adverse events over the lifespan could produce greater health risks in later life (Dannefer, Reference Dannefer2003; Ferraro and Shippee, Reference Ferraro and Shippee2009). So, the inverse relationship between IPV and TL should become stronger across the lifespan. Indeed, a cohort of women aged 35–74 years who had a sister with breast cancer found an association between perceived stress and shorter TL only among women aged 55 years and older (Parks et al., Reference Parks, Miller, McCanlies, Cawthon, Andrew, DeRoo and Sandler2009). Conversely, the age-as-leveller theory argues that inequalities in health reduce across the lifespan (House et al., Reference House, Lepkowski, Kinney, Mero, Kessler and Herzog1994; Lauderdale, Reference Lauderdale2001). Studies support the age-as-leveller position that stressful life events were inversely associated with TL in adults aged 22–44 but not in adults aged 45–69 (McFarland et al., Reference McFarland, Taylor, Hill and Friedman2018). Our current results are consistent with the age-as-leveller theory. Older adults may be more likely to report age-related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (Gruber et al., Reference Gruber, Semeraro, Renner and Herrmann2021) that are associated with TL shortening. These diseases may cover up the independent influence of psychosocial stressors (Schaakxs et al., Reference Schaakxs, Wielaard, Verhoeven, Beekman, Penninx and Comijs2016). This, however, seems counterintuitive as TL shortening is reflective of an accumulation of ‘wear and tear’ from a range of exposome features that act both cumulatively, synergistically and independently (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Schurgers, Shiels and Stenvinkel2021; Mafra et al., Reference Mafra, Borges, Lindholm, Shiels, Evenepoel and Stenvinkel2021). Another possibility is that older adults with the most damaged TL may not participate in the study because of health issues or death (Schaakxs et al., Reference Schaakxs, Wielaard, Verhoeven, Beekman, Penninx and Comijs2016); this healthy survivor effect without subjects with the most shortened TL might underestimate the true relationship between IPV and TL. Given these explanations are tentative and the nature of retrospective design, future studies with more robust methodologies including serial measurement of TL are needed to further explore this topic.

The present study underscores some complexities of research into IPV and TL. First, each type of IPV was negatively associated with TL and the association was strongest in physical violence. Existing studies on the relationship between IPV and TL found inconsistent results (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Epel, Cooper, Lin, Blackburn and Lee2012; Jodczyk et al., Reference Jodczyk, Fergusson, Horwood, Pearson and Kennedy2014), and very few further investigated the associations of different and multiple types of IPV with TL. The influence of different types of violence in early life on TL may provide insights into understanding the issue and show inconsistent results. Vincent et al. (Reference Vincent, Hovatta, Frissa, Goodwin, Hotopf, Hatch, Breen and Powell2017) found no associations between physical/sexual/emotional violence and TL from a UK sample (ages 20–84). However, a study of 1135 women (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Prescott, Tworoger, De Vivo and Rich-Edwards2015) has found stronger evidence of an association between physical violence and TL than sexual violence, consistent with our findings. Our current study extends previous work exploring the influence of all three types of IPV. All three types of IPV showed negative relationships with TL in unadjusted models, suggesting the importance of comprehensively evaluating all three types of IPV.

Secondly, there was a dose–response relationship between number of types of IPV and TL. This finding echoes the allostatic load model that highlights the cumulative impact of multiple sources of stress (Danese and McEwen, Reference Danese and McEwen2012). This notion was also evidenced in the influence of stressful childhood events on TL, with a relatively consistent result showing a critical role of cumulative childhood stress on TL (Shalev et al., Reference Shalev, Moffitt, Sugden, Williams, Houts, Danese, Mill, Arseneault and Caspi2013; Puterman et al., Reference Puterman, Gemmill, Karasek, Weir, Adler, Prather and Epel2016). Researchers of adulthood stress also call for investigations on cumulative stressors (van Ockenburg et al., Reference van Ockenburg, Bos, de Jonge, van der Harst, Gans and Rosmalen2015; Verhoeven et al., Reference Verhoeven, van Oppen, Puterman, Elzinga and Penninx2015). Our current findings suggest that identifying victims with multiple types of IPV might be beneficial if system-level interventions are in place (Hamberger et al., Reference Hamberger, Rhodes and Brown2015). Additional research is needed to explore further this critical issue, including assessing IPV duration and severity.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study is the use of a relatively large sample using UKB (N = 144 049) of both sexes, providing sufficient power to detect differences. In addition, we were able to explore the separate and combined effects of different types of IPV and, therefore, demonstrate a dose–response relationship. Certain limitations and considerations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the exposure to IPV was recalled retrospectively and therefore may have been subject to recall bias. The IPV measurement also has no metrics of validity and reliability. As a result of the potential reporting bias and residual confounding, we should not interpret causality from the findings of this study. Secondly, there were minimal data on the duration, frequency and severity of violence in the data. Thirdly, TL was only available as T/S ratio rather than differences in base pairs. Fourthly, with the small effect size, some tests, particularly in subgroup analysis, could have been underpowered. Last but not least, UK Biobank is not representative of the general UK population with a healthy volunteer bias, particularly among those who completed the online mental health survey (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Celis-Morales, Gray, Petermann-Rocha, Lyall, Mackay, Sattar, Minnis and Pell2020). This could explain the stronger association in younger age group and distort the association estimates if the participation was caused by both IPV and TL, even though it does not appear likely. Previous analysis has shown that the association estimates from the UK Biobank are comparable to that from population-representative cohorts (Batty et al., Reference Batty, Gale, Kivimaki, Deary and Bell2020).

Implications

The significant relationship between IPV and TL has real-world implications. Given that all three types of IPV are linked to TL, clinical practitioners need to comprehensively identify all types of IPV, especially physical IPV which had the strongest individual association, and multiple IPV which had the strongest overall association. Importantly, these provide further evidence for prioritising intervention for those individuals. While causality cannot be established from this study, future studies should examine whether TL is a mechanism and/or a risk marker, which would provide the basis to use TL as a prognostic factor in clinical practice.

Conclusions

IPV was associated with TL in a dose–response pattern. Further studies should explore the association of violence with changes in TL over time, as well as to which extent these translate to adverse health outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796023000112.

Availability of data and materials

The data can be requested from the UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to UK Biobank participants. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 7155.

Author contributions

K. L. C. conceptualised and designed the study, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. C. K. M. L. and X.-Y. C. assisted in study conceptualisation, interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. P. I., W. C. L., P. G. S., H. M. and J. P. P. interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. F. K. H. conceptualised and designed the study, collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Financial support

UK Biobank was established by the Wellcome Trust medical charity, Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Scottish Government and the Northwest Regional Development Agency. This study was supported by Glasgow Children's Hospital Charity (Project No.: GCHC/SPG/2021/05), Hong Kong Research Grants Council (Project No.: PolyU 15602419) and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Project Code: 1-ZE1R).

Conflict of interest

None.