Introduction

Depression is one of the leading causes of mental health-related disability and is associated with social and economic burden (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Chisholm, Parikh, Charlson, Degenhardt, Dua, Ferrari, Hyman, Laxminarayan, Levin, Lund, Medina Mora, Petersen, Scott, Shidhaye, Vijayakumar, Thornicroft and Whiteford2016). Its onset usually occurs in mid-late adolescence (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2022). Depression in young people is an increasing concern not only because its onset occurs during a turbulent transitory period (Eyre et al., Reference Eyre, Bevan Jones, Agha, Wootton, Thapar, Stergiakouli, Langley, Collishaw, Thapar and Riglin2021), but also because of its increasing prevalence, high recurrence rates and continuity into adulthood (Collishaw, Reference Collishaw2015; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Riglin, Thapar, Heron, Anney, O’Donovan and Thapar2019; Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Eyre, Patel and Brent2022). Depression can spontaneously remit, recur or persist especially among young people, due to substantial variability in the course of the illness in this group (Schubert et al., Reference Schubert, Clark, Van, Collinson and Baune2017; Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Eyre, Patel and Brent2022). Depression in this age group can also be the harbinger or first onset of other disorders such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia (Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Davey, Hetrick, Alvarez-Jimenez, Voutier, Bechdolf, McGorry, Scott, Berk and Cotton2017; Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Eyre, Patel and Brent2022). Although not all adolescents with significant psychopathology continue to have serious emotional problems in adulthood, many struggle with chronic and recurrent depression for extended periods of time, which is associated with poor adverse outcomes in the long term (Morales-Muñoz et al., Reference Morales-Muñoz, Mallikarjun, Chandan, Thayakaran, Upthegrove and Marwaha2023). Many young people with severe and complex depression do not respond to first-line treatments and are at greater risk for suicidal ideation and attempts (Davey and McGorry, Reference Davey and McGorry2019). Therefore, characterising the differing trajectories of depressive symptoms over this critical period is crucial to aid assessment of prognosis and tailor early intervention strategies (Davey and McGorry, Reference Davey and McGorry2019; Marwaha et al., Reference Marwaha, Brown and Davey2021).

Although early intervention for depression in young people is still a blind spot (McGorry and Mei, Reference McGorry and Mei2018), a growing range of treatments and early intervention initiatives with evidence of efficacy for depression have been developed in the last decades (Hett et al., Reference Hett, Rogers, Humpston and Marwaha2021; Marwaha et al., Reference Marwaha, Palmer, Suppes, Cons, Young and Upthegrove2023). However, to enable potentially preventative approaches, further research is still needed to identify and target interventions towards the most salient factors associated with persistent depression to alter this worrying illness trajectory. To date, several candidate common clinical factors relevant to prevention and intervention for depression in young people have been detected, such as early and persistent adversity (between ages 9 and 11; Weavers et al., Reference Weavers, Heron, Thapar, Stephens, Lennon, Bevan Jones, Eyre, Anney, Collishaw, Thapar and Rice2021), parental psychopathology, irritability and anxiety (between ages 9 and 17; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Sellers, Hammerton, Eyre, Bevan-Jones, Thapar, Collishaw, Harold and Thapar2017), gender, low socio-economic status (SES) and the quality of interpersonal relationships (between ages 4 and 17; Shore et al., Reference Shore, Toumbourou, Lewis and Kremer2018), loneliness (between ages 9 and 18; Dunn and Sicouri, Reference Dunn and Sicouri2022), inflammation (until age 18; Toenders et al., Reference Toenders, Kottaram, Dinga, Davey, Banaschewski, Bokde, Quinlan, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Garavan, Gowland, Heinz, Brühl, Martinot, Paillère Martinot, Nees, Orfanos, Lemaitre, Paus, Poustka, Hohmann, Fröhner, Smolka, Walter, Whelan, Stringaris, van Noort, Penttilä, Grimmer, Insensee, Becker, Schumann and Schmaal2022a) and baseline severity of depressive symptoms and neuroticism (ages between 14 and 16; Toenders et al., Reference Toenders, Laskaris, Davey, Berk, Milaneschi, Lamers, Penninx and Schmaal2022b). However, there is still little consensus on what the most relevant modifiable factors (e.g., sleep-wake cycle patterns, early life stress) for depression in young people are and targeting modifiable factors is an additional, promising strategy for depression prevention (Marino et al., Reference Marino, Andrade, Campisi, Wong, Zhao, Jing, Aitken, Bonato, Haltigan, Wang and Szatmari2021). It is crucial to identify early life factors in childhood that could be potentially modifiable, which would follow a recent study from our group that found that young people with persistent depression are at highest risk of adverse outcomes in young adulthood (Morales-Muñoz et al., Reference Morales-Muñoz, Mallikarjun, Chandan, Thayakaran, Upthegrove and Marwaha2023).

Most studies in this area have focused on depression at a single time point, rather than exploring those individuals with chronic depression longitudinally. This approach does not capture intraindividual variability in symptoms or the longitudinal course of depressive symptoms (Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Byers, Falvey, Simonsick, Satterfield, Ayonayon, Smagula, Rubin and Yaffe2016). Various modifiable factors could contribute to an individual’s vulnerability to develop chronic depression, and understanding the composition of these modifiable factors is essential for planning effective prevention strategies (Avenevoli et al., Reference Avenevoli, Swendsen, He, Burstein and Merikangas2015). Therefore, identifying children and/or adolescents who are at highest risk for developing chronic depression and consequently further adverse outcomes is of utmost importance, so that we can develop more effective and targeted interventions to attenuate the risk trajectory of depression.

To address the current gap in the literature on depression in young people, the objectives of this study are to: (1) characterise the trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood from age 12.5 to 22 years; and (2) identify key potentially modifiable factors occurring in childhood before age 11 that associate with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms. We hypothesise that different trajectories of depressive symptoms are detectable across childhood and adolescence, including one with persistent depressive symptoms; and that several factors (e.g., poor sleep, feeling lonely or high levels of inflammation) in childhood would be associated with higher risk of persistent depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood.

Methods

Participants

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a UK birth cohort study, examining the determinants of development, health and disease during childhood and beyond (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Golding, Macleod, Lawlor, Fraser, Henderson, Molloy, Ness, Ring and Smith2013; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, Macdonald-wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding, Smith, Henderson, Macleod, Molloy, Ness, Ring, Nelson and Lawlor2013; Northstone et al., Reference Northstone, Ben Shlomo, Teyhan, Hill, Groom, Mumme, Timpson and Golding2023). Pregnant women resident in Avon, UK with expected dates of delivery between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992 were invited to take part. The initial number of pregnant women enrolled was 14,541. Of these births, 13,988 children were alive at age 1 year. In addition, 913 children were enrolled after age 7 years, giving a total sample of 14,901 children. For this study, we used data from 6711 participants comprising offspring who had reported information on the depressive symptoms assessment at the age of 12.5 years old (see Figure S1 for a flow chart detailing sample definition). Further details of the ALSPAC are provided in Supplement. Ethical approval was obtained from the ALSPAC’s Law and Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the children.

Measures

Depressive symptoms in young people

The Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ; Angold et al., Reference Angold, Costello, Messer and Pickles1995) was used to measure depressive symptoms at 12.5, 13.5, 16, 17.5, 21 and 22 years old. We selected these time points for two main reasons: (1) these were available within ALSPAC; (2) allows to cover key developmental stages from early adolescence, adolescence, late adolescence and young adulthood. SMFQ is a 13-item self-reported questionnaire enquiring about the occurrence of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. The participants rate each statement as 2 (true), 1 (sometimes true) or 0 (not true), with total scores ranging from 0 (minimum) to 26 (maximum). Further, there is evidence supporting the validity of SMFQ to measure depression in young adults in the general population using ALSPAC (Eyre et al., Reference Eyre, Bevan Jones, Agha, Wootton, Thapar, Stergiakouli, Langley, Collishaw, Thapar and Riglin2021), with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92, and high accuracy for discriminating Major Depression Disordercases from non-cases (Area Under the Curve = 0.92). The commonly used cut-point in young people is ≥12 for screening for depression (Eyre et al., Reference Eyre, Bevan Jones, Agha, Wootton, Thapar, Stergiakouli, Langley, Collishaw, Thapar and Riglin2021). Here, we used the SMFQ total score, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms.

Factors

In this study, factors refer to several modifiable biological, psychological, environmental, social or family-related characteristics occurring in childhood before age 11 that precede and are associated with a higher likelihood of depression. We focus on factors occurring before age 11, as this is a critical transition period for most children in the UK for two main reasons: (1) this refers to the beginning of puberty on average (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Fraser, Gunnell, Joinson and Mars2020) and (2) most children move from primary to secondary school in the UK. Accordingly, we selected the following factors available in ALSPAC for analysis, including bullying, omega-3 and parenting style at 7 years, diet at 7.5 years, intelligence quotient (IQ) and friendship quality at 8 years, childhood abuse up to 8 years old, locus of control and self-esteem at 8.5 years, engagement with arts, religious beliefs, inflammatory levels (c-reactive protein and interleukin-6), night-time sleep duration and bedtime at 9 years, loneliness, attentional switching, attentional control and selective attention at 10 years and participation in outdoor activities, school connectedness and school enjoyment at 11 years. When selecting these factors, we used the existing list of factors suggested by Wellcome Trust (Abas, Reference Abas2022; Wolpert et al., Reference Wolpert, Pote and Sebastian2021) and selected those available in ALSPAC in the first stage. We then finalised the list of relevant factors for this study following lived experience feedback.

A more detailed description of each of these factors appear in Table S1 in Supplement.

Confounders

Child’s sex, preterm delivery and temperament and parent-reported ethnicity (white and non-white) and SES were selected as covariates because of their impact on depression (Gelaye et al., Reference Gelaye, Rondon, Araya and Williams2016; Harron et al., Reference Harron, Gilbert, Fagg, Guttmann and van der Meulen2021). Here, confounders occurred prenatally, at birth or during the first 2 years of life, and were non-modifiable or intrinsic variables (e.g., temperament, mental health), to differentiate from the factors, which occurred in childhood from 7 to 11 years old, and were all modifiable factors (i.e., more easily influenced from the outside). SES was mother-reported using the Cambridge Social Interaction and Stratification Scale (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Prandy and Blackburn1973). Prenatal maternal education was measured by asking mothers the highest qualification they achieved. Postnatal maternal depression (at 8 months) was measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987). Finally, for child’s temperament at age 2, parents completed the Carey Infant Temperament Scale (Fullard et al., Reference Fullard, Mcdevitt and Carey1984).

Statistical analysis

A three-staged analysis plan was developed. In the first stage, descriptive analyses were conducted in SPSS, v29. Second, latent class growth analysis (LCGA) was conducted using Mplus-v8 (Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017) to assess trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood. The indicator variables were SMFQ total scores at 12.5, 13.5, 16, 17.5, 21 and 22 years. We fitted five models by increasing the number of classes (Jung and Wickrama, Reference Jung and Wickrama2008; i.e., 2–6 classes). The best model was initially chosen based on fit indices (i.e., Bayesian information criteria [BIC] and Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin [VLMR] test) as well as model entropy. Lower BIC values suggest better model fit and a significant VLMR value suggests that a (k)-class model fits the data better than a (k − 1)-class model. Entropy was used to select the best model fit in addition to BIC and VLMR; entropy with values approaching 1 indicates clear delineation of classes. We applied the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method (Jung and Wickrama, Reference Jung and Wickrama2008) which makes a missing at random assumption, permitting partially incomplete data to be included (Wardenaar, Reference Wardenaar2022). Third, we investigated the prospective associations between factors by age 11 and the trajectory of persistent high levels of depressive symptoms identified with LCGA (i.e., outcome), using logistic regression analyses. For the outcome, we created a dichotomous variable, based on the best model fit class obtained from LCGA: the class representing persistent high depressive symptoms was recoded as 1, while the other classes were recoded as 0. Additionally, we first tested unadjusted associations, and then we controlled for all the confounders in the adjusted model with each different factor. As primary analyses, we first tested these regression models with each factor as independent variable in separate models, and then we applied an additional regression analyses where we included a combination of these significant univariable factors together in the same model as factors, based on the feedback provided by young person with lived experience. More specifically, our co-author with lived experience in mental health (i.e., our lived experience lead) led several meetings with the Youth Advisory Group (YAG) from the University of Birmingham’s Institute for Mental Health, which comprises 18 young people aged 18–25 years old with mental health problems. During these meetings, our lived experience lead presented this study and the variables to be selected for the analyses to the YAG and received feedback regarding the most relevant factors for depression in young people based on lived experience. A list of factors was agreed at the end of these meetings between our lived experience lead and the YAG. These factors were highlighted as those that could have interactions with each other that made sense to individuals with lived experience of depression and were loneliness, IQ, school connectedness, school enjoyment, friendship, parenting and sleep. As secondary analyses, we conducted a logistic regression model in which we included as independent variables only those variables that were statistically significant in the separate regression analyses (from the primary analyses above). Further, we applied multinomial regression analyses, including as factors those from the combined logistic regression analyses (from the primary analyses above), and all the classes from the model with best model fit as the outcome. We used as reference the class with the largest sample size.

Finally, and as sensitivity analyses, we conducted the analyses above again excluding the loneliness item (‘I felt lonely’) from the SMFQ total score, to potentially control for any potential overlap between this item and our factor on loneliness.

As 57.1% of the original sample was lost to attrition at 12.5 years, we conducted logistic regressions to identify significant factors of attrition (see Supplementary, Table S2). Using the variables associated with selective dropout as the factors, we fitted a logistic regression model to determine weights for each individual using the inverse probability of response.

Results

51% of our sample were female, 96.5% were White and 7.9% were born premature. Table 1 shows the frequencies and descriptive values of all the variables of interest in this study.

Table 1. Descriptive variables of our sample (N = 6711) (factors, outcomes and covariates)

CRP = C-reactive protein, IL-6 = interleukin 6, SMFQ = Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, WISC = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, IQ = intelligence quotient, N = number, SD = standard deviation.

Latent classes of depressive symptoms

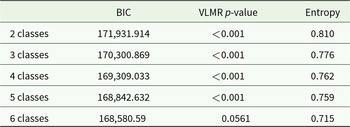

Table 2 shows VLMR, BIC and entropy for all five classes. Overall, a four-class model provided the best model fit. Although the five-class model had the lowest BIC and was statistically significant compared with the four-class model, the four-class model reported higher entropy value, suggesting a higher classification precision than class 5. Based on the class distinctiveness, clinical relevance and interpretability, the four-class model was identified as optimal for depressive symptoms. Additionally, the four-class model provided large enough (e.g., >3%) group sizes for each class.

Table 2. BIC, VLMR likelihood test p-values and entropy for Classes 2–6 of the SMFQ total score of depressive symptoms

BIC = Bayesian information criteria, VLMR = Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin.

Number of cases LCGA – two classes: Class 1 = 1489 (17.1%), Class 2 = 7216 (82.9%).

Number of cases LCGA – three classes: Class 1 = 701 (8.1%), Class 2 = 1047 (12.0%), Class 3 = 6957 (79.9%).

Number of cases LCGA – four classes: Class 1 = 312 (3.6%), Class 2 = 1010 (11.6%), Class 3 = 910 (10.5%), Class 4 = 6473 (74.4%).

Number of cases LCGA – five classes: Class 1 = 211 (2.4%), Class 2 = 258 (3.0%), Class 3 = 977 (11.2%), Class 4 = 1046 (12.0%), Class 5 = 6213 (71.4%).

Number of cases LCGA – six classes: due to VLMR p-value > 0.050, a model with six classes was not detected.

Figure 1 shows the trajectories of the four-class model. Class 1 ‘persistent high levels of depressive symptoms’ (3.6%) was characterised by a chronic course of depressive symptoms, with the highest burden of depressive symptoms. Class 2 ‘moderate levels of depressive symptoms’ (11.2%) described a reducing moderate trajectory. Class 3 ‘increasing levels of depressive symptoms’ (10.5%) showed a gradual increase of symptoms. Finally, Class 4 ‘persistent low levels of depressive symptoms’ (74.7%) had a persistent lower level of course trajectory.

Figure 1. Growth trajectories of depressive symptoms across childhood to adolescence. The latent class growth analyses detected a best model fit for four classes. Class 1 (blue line on the top) represents individuals with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms across time points. Class 2 (red line in the middle) represents individuals with persistent moderate levels of depressive symptoms. Class 3 (green line) represents individuals with increasing levels of depressive symptoms. Class 4 (purple line on the bottom) represents individuals with persistent low levels of depressive symptoms.

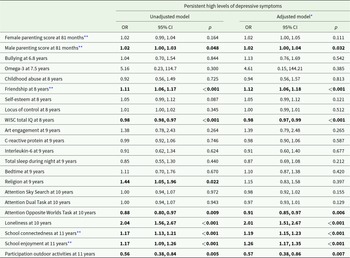

Factors and persistent high levels of depressive symptoms

When we applied separate logistic regression models for each factor, we found that several factors were significantly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms in the adjusted model (see Table 3). More specifically, higher loneliness score at 10 (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.51–2.67; p < 0.001); lower participation in outdoor activities at 11 (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.38–0.86; p = 0.007); lower attentional control at 10 (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85–0.97; p = 0.006); lower IQ at 8 (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97–0.99; p < 0.001); feeling less connected with the school at 11 (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.15–1.23; p < 0.001); lower school enjoyment at 11 (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.17–1.35; p < 0.001); lower friendship quality at 8 (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.06–1.18; p < 0.001); health conscious/vegetarian diet at 8.6 (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05–1.41; p = 0.009) and worse paternal parenting at 7 (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00–1.04; p = 0.032) were all significantly associated with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood.

Table 3. Associations between factors and persistent high levels of depressive symptoms from 12.5 months to 22 years, in separate models per active risk factor

OR = odds ratio.

* Adjusted model controlled for sex, ethnicity, SES, temperament at 2 years and preterm, and maternal postnatal depression at 8 months.

** These variables were invertedly coded, with higher scores indicating worse outcomes, and lower scores better outcomes.

Each predictor was included in separate regression analyses together with the covariates (for the adjusted models).

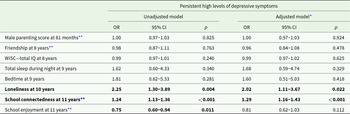

Associations between combination of factors with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms

We also tested the associations between a combination of factors (which was created based on the feedback by lived experience, rather than using other statistical approaches such as factor analyses) with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood (see Table 4). In the adjusted model, we found that only higher loneliness (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.11–3.67; p = 0.022) and lower school connectedness (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.16–1.43; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood.

Table 4. Associations between combined factors and persistent high levels of depressive symptoms

OR = odds ratio.

* Adjusted model controlled for sex, ethnicity, SES, temperament at 2 years, preterm and maternal postnatal depression at 8 months.

** These variables were invertedly coded, with higher scores indicating worse outcomes, and lower scores better outcomes. Note 1: The selection of these factors was done based on lived experience involvement. Here, all the factors were included together within the same regression analyses model.

As a sensitivity analyses, we conducted an additional regression analyses model, where we included in the same model all the factors that appeared statistically significant in the separate regression analyses models (from Table 3). Importantly, we again found that only higher loneliness (OR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.18–4.11; p = 0.013) and lower school connectedness (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.19–1.49; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms, which supports the robustness of our results (see Table S3, Supplement).

The results from the multinomial regression analyses when we compared class 1 (i.e., our class of interest) versus class 4 (i.e., reference class) showed similar results as above, with higher loneliness (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.24–2.36; p < 0.001) and lower school connectedness (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00–1.03; p = 0.004) being the only significant factors (see Table S4, Supplement).

Finally, our sensitivity analyses when we excluded the item on loneliness from the SMFQ total score reported similar results. Briefly, similar trajectories of depressive symptoms were reported, with a four-classes model providing the best model fit. Further, loneliness and lack of connection with school were still the only factors that were significantly associated with persistent high levels of depressive symptoms when we combined relevant factors together in the analyses. Further details are provided in Supplement (Tables S5–S8 and Figure S2).

Discussion

Using data from a large population-based cohort study, we identified four different trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood. Further, we detected a range of modifiable factors in childhood that were associated with increased risk of developing high levels of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood. Both findings were consistent with our initial hypotheses. We build on our previous work on the long-term adverse outcomes associated with chronic depressive symptoms and examined what factors might explain this (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Model of depressive symptoms across adolescence, risk factors and impacts. Here we present how specific risk factors before age 11 (and especially loneliness and not feeling connected at school) lead to chronic depressive symptoms across adolescence, which subsequently leads to the development of a range of adverse outcomes in young adulthood, including mental health, physical health and functioning problems. On top (in brown colour) we present the main purpose of this current study, while on the bottom (in blue colour) we present the main findings of our recent study (Morales-Muñoz et al., Reference Morales-Muñoz, Mallikarjun, Chandan, Thayakaran, Upthegrove and Marwaha2023). More specifically, in our recent study, we found that chronic depression across adolescence led to a range of mental health (psychotic disorder, severe depression, generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder), physical health (asthma, arthritis and heart problems) and functioning problems (not being in education/employed/training), all at 24 years old.

First, we found four different trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood including persistent high and persistent low levels, which is consistent with previous work (Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian, Reference Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian2018; Weavers et al., Reference Weavers, Heron, Thapar, Stephens, Lennon, Bevan Jones, Eyre, Anney, Collishaw, Thapar and Rice2021). More specifically, similar to our findings, all of the previous studies above detected a low stable group which represented the vast majority of the sample. Persistently high depression group trajectories have also been found in previous research supporting the relevance of chronicity of depression in youth (Bulhões et al., Reference Bulhões, Ramos, Severo, Dias and Barros2021; Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019; Shore et al., Reference Shore, Toumbourou, Lewis and Kremer2018; Weavers et al., Reference Weavers, Heron, Thapar, Stephens, Lennon, Bevan Jones, Eyre, Anney, Collishaw, Thapar and Rice2021). Further, in line with previous research (Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, López-López, Hammerton, Manley, Timpson, Leckie and Pearson2019; Weavers et al., Reference Weavers, Heron, Thapar, Stephens, Lennon, Bevan Jones, Eyre, Anney, Collishaw, Thapar and Rice2021), increasing levels of depressive symptoms and persistent levels of depressive symptoms differed in their age of onset, with an earlier age (starting at or before age 12.5 years) for persistent levels than increasing levels of depressive symptoms (starting at age 16 years). However, some other studies have reported slightly different depression trajectories to ours. For example, Cumsille et al. (Reference Cumsille, Martínez, Rodríguez and Darling2015), Duchesne and Ratelle (Reference Duchesne and Ratelle2014), Essau et al. (Reference Essau, de la Torre-luque, Lewinsohn and Rohde2020), Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian (Reference Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian2018) and Weavers et al. (Reference Weavers, Heron, Thapar, Stephens, Lennon, Bevan Jones, Eyre, Anney, Collishaw, Thapar and Rice2021) detected remitting trajectories. It is likely that the differences may arise due to methodological variations across the studies, such as age range (e.g., Essau et al., Reference Essau, de la Torre-luque, Lewinsohn and Rohde2020), measures used (e.g., Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian, Reference Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian2018), number of assessments (e.g., Bulhões et al., Reference Bulhões, Ramos, Severo, Dias and Barros2021), duration of the follow-up (e.g., Duchesne and Ratelle (Reference Duchesne and Ratelle2014) and confounders included (e.g., Ferro et al., Reference Ferro, Gorter and Boyle2015).

Second, in relation to the associations between factors in childhood and persistent high levels of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood, we found that overall, the most relevant factors were loneliness and not feeling connected with the school, which is consistent with previous research in the field. For example, previous research found that family and school connectedness were negatively associated with depression and suicidal ideation (Arango et al., Reference Arango, Cole-Lewis, Lindsay, Yeguez, Clark and King2019) and that increasing school connectedness should be considered as a universal adolescent mental health strategy (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Jamshidi, Berger, Reupert, Wurf and May2022; Langille et al., Reference Langille, Asbridge, Cragg and Rasic2015). Further, the existing evidence supports that higher levels of loneliness are linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents (Dunn and Sicouri, Reference Dunn and Sicouri2022), and that childhood loneliness is a major predictor for anxiety and depressive disorders in young adults (Xerxa et al., Reference Xerxa, Rescorla, Shanahan, Tiemeier and Copeland2023), providing some external validation of our results. Some of the potential explanations for why loneliness and social connectedness were the most relevant factors for chronic depression in our study might be found in the fact that adolescence is a period in which the social brain undergoes structural development, such as heightened self-awareness and social understanding (Kilford et al., Reference Kilford, Garrett and Blakemore2016). Adolescents, while developing cognitive maturation, start to form more complex and hierarchical peer relationships and are more sensitive to acceptance and rejection by their peers compared to children (Kilford et al., 2016; King et al., Reference King, McLaughlin, Silk and Monahan2018). Perceived social connectedness and loneliness may thus be key. It is suggested that the problem of current prevention of depression is that it is not structurally and socially embedded (Ormel et al., Reference Ormel, Cuijpers, Jorm and Schoevers2019). Schools and colleges may be very suitable settings for identifying and treating young people at highest risk of developing chronic depression, although continued optimisation and refinement of school based interventions is needed to enhance their impact (Werner-Seidler et al., Reference Werner-Seidler, Spanos, Calear, Perry, Torok, O’Dea, Christensen and Newby2021). However, the bidirectional associations of these two factors with depression should be taken into consideration when interpreting our results, as both loneliness (Achterbergh et al., Reference Achterbergh, Pitman, Birken, Pearce, Sno and Johnson2020) and lack of connection with the school (Marraccini and Brier, Reference Marraccini and Brier2017) are also considered a symptom for depression in young people. In the current study, we explored and found evidence that both factors precede the development of chronic depressive symptoms from childhood to adulthood, but future studies should further explore the prospective associations of chronic depression in young people with loneliness and school connectedness.

Implications for practice

There are several implications. Firstly, the timing of the onset of depression is important in chronic course; the earlier depression starts, the greater the risk that it could be chronic (Thapar and Riglin, Reference Thapar and Riglin2020). Chronicity is not only important because of individual and family suffering, and social consequences, but because chronic depressive trajectories in youth are associated with transition to other severe mental disorders (Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Nelson, Ratheesh, Treen and McGorry2019; McGorry et al., Reference McGorry, Hartmann, Spooner and Nelson2018; Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Hammond, Gao, Marwaha, Thompson, Hartmann, Davey, Zammit, Berk, McGorry and Nelson2023) such as bipolar disorder (Durdurak et al., Reference Durdurak, Altaweel, Upthegrove and Marwaha2022; Ratheesh et al., Reference Ratheesh, Davey, Hetrick, Alvarez-Jimenez, Voutier, Bechdolf, McGorry, Scott, Berk and Cotton2017). The same trajectory patterns for increasing and persistent classes have also been detected in older adult communities (Mirza et al., Reference Mirza, Wolters, Swanson, Koudstaal, Hofman, Tiemeier and Ikram2016), suggesting patterns of chronicity are similar across the lifespan. Secondly, the identified factors have direct clinical and childhood policy relevance. Screening for clinically relevant depressive symptoms among children and providing early intervention at schools may be an effective strategy to reduce the burden of disease from depression in children and adolescents (Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Davies, Hetrick, Palmer, Caro, López-López, Gunnell, Kidger, Thomas, French, Stockings, Campbell and Welton2019; Garcia-Carrion et al., Reference Garcia-Carrion, Villarejo and Villardón-Gallego2019) while also looking at the role of school personnel in the detection, referral and provision of help for youth psychopathology due to their influence on the outcomes (Werner-Seidler et al., Reference Werner-Seidler, Spanos, Calear, Perry, Torok, O’Dea, Christensen and Newby2021). Thirdly, the timing of such interventions should be a central component of these efforts, and our findings suggest that these early interventions should start as early as 11-year-old, which is a key transition period for many children. Since universal interventions are less effective than targeted intervention (Werner-Seidler et al., Reference Werner-Seidler, Spanos, Calear, Perry, Torok, O’Dea, Christensen and Newby2021) and depression in children and adolescents is considerably undertreated (Mojtabai et al., Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and Han2016), the development of youth-specific specialist integrated mental health services for young people is particularly crucial for the public mental health service systems which would strengthen existing child and adolescent services (Mcgorry et al., Reference Mcgorry, Purcell, Hickie and Jorm2007). Our findings support the widespread call for an investment in young people’s mental health, by identifying where and when this might be targeted to prevent chronicity of depressive symptom burden (Kieling et al., Reference Kieling, Buchweitz, Caye, Silvani, Ameis, Brunoni, Cost, Courtney, Georgiades, Merikangas, Henderson, Polanczyk, Rohde, Salum and Szatmari2024).

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the repeated assessment of depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood and the broad assessment of factors for depressive symptoms in a large population-based sample. Further, a young person with lived experience from our team together with a wider group of young people with lived experience provided substantial feedback and insight including definition of the research priorities, selection of factors and interpretation of our findings. However, our study has also some limitations. First, the majority of participants were of white ethnicity, which limits the generalisability of our findings to other ethnic groups. Second, although we controlled for maternal postnatal depression in this study, we did not look at the role of anxiety and other parental psychopathology which are factors of major depressive disorders (stages 0–2; Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Nelson, Ratheesh, Treen and McGorry2019). Given that this is a birth cohort study and not a high-risk study, the role of parental psychopathology is something that needs further exploration in future studies, especially in high-risk population, rather than the general population. Third, since the informant differed for the assessment of some of the factors (i.e., parent-reported vs self-reported), clinically relevant symptoms might have been missed such as childhood trauma and bullying, which were parent-reported. Further, depression was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire (SMFQ) rather than a direct interview. Although SMFQ is considered a valid instrument to measure depression in young people (Eyre et al., Reference Eyre, Bevan Jones, Agha, Wootton, Thapar, Stergiakouli, Langley, Collishaw, Thapar and Riglin2021), this is still subject to potential bias. Fourth, although this work was co-produced with a young person with lived experience liaising with a small group of young people with lived experience from Birmingham area, this could be also subject to some bias as it was limited to a specific group of people. Fifth, although a relatively large number of factors were examined, some other relevant factors (e.g., anxiety, neurodevelopmental conditions, genetic factors, family history of psychopathology) were not included (Maciejewski et al., Reference Maciejewski, Hillegers and Penninx2018; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Sellers, Hammerton, Eyre, Bevan-Jones, Thapar, Collishaw, Harold and Thapar2017; Vidal-Ribas et al., Reference Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft and Stringaris2016). In addition, other relevant confounders (such as sexual orientation) were not available within our dataset, and thus we were not able to control for them. Sixth, LCGA do not necessarily identify and reflect the true clinical sub-populations, but rather those that fit optimally according to currently default criteria for evaluation model fit in Mplus (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Ganocy, Mount, Youngstrom, Frazier, Fristad, Horwitz, Birmaher, Findling, Kowatch, Demeter, Axelson, Gill and Marsh2014). Seventh, since there were high rates of attrition, this might have caused bias in estimates of the associations we found (Cornish et al., Reference Cornish, MacLeod, Boyd and Tilling2021). However, to be able to reduce this bias we have utilised FIML and inverse probability weighting methods. Another bias that might have arisen in our findings is the previously detected lack of measurement invariance for the SMFQ assessment at age 12.5 in ALSPAC (Schlechter et al., Reference Schlechter, Wilkinson, Ford and Neufeld2023). Eighth, although working with people with lived experience in mental health research carries a wide range of benefits, lived experience perspectives could be criticised as being limited by their subjectivity (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Pinfold, Catchpole, Lovelock, Senthi and Kenny2024). However, majority of the research relies on background assumptions and involving lived experience work in research can increase the relevance, feasibility, adoption, implementation and sustainability of research, particularly in mental health research (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Pinfold, Catchpole, Lovelock, Senthi and Kenny2024).

Conclusion

Our findings support the existence of different trajectories of depressive symptoms across adolescence and young adulthood, including a group of young people with persistent high depressive levels. Further, we found that loneliness and social connection before age 11 were the most relevant factors for chronic depressive symptoms in young people and these could be addressed in depression prevention programs. Our findings contribute to the existing research in depression with the identification of those children who are at highest risk for developing persistent depressive symptoms. Prevention has been the most neglected aspect of depression, and our findings add to growing evidence about the urgent need of improving early intervention strategies to prevent the experience of chronic depression in adulthood.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796024000350.

Availability of data and materials

Access to ALSPAC data is through a system of managed open access (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/access/).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses.

Author contributions

This publication is the work of the authors and IMM and BD will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. S. Marwaha and I. Morales-Muñoz contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref.: 226698/Z/22/Z) and supported by the NIHR Mental Health Translational Research Collaboration. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The ALSPAC was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant ref.: 217065/Z/19/Z), and the University of Bristol provided core support for ALSPAC. SM is supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre. The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.