Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic poses an unprecedented mental health threat globally as a consequence of the fear of contraction, as well as government reaction to containing community spread (e.g. economic shut down, unemployment). Replicated studies from around the world have reported on the increased prevalence of mental disorders as a result of COVID-19, including depression, anxiety and insomnia (i.e. prevalence of 10.6%−50.7%, 10.4%−44.7% and 33.9%−36.1%, respectively) (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ma, Wang, Cai, Hu, Wei, Wu, Du, Chen, Li, Tan, Kang, Yao, Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu and Hu2020; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Zhang, Xiang, Liu, Hu and Zhang2020; Potloc Study, 2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, McIntyre, Choo, Tran, Ho, Sharma and Ho2020b; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Yin, Zhao, Xue, Peng, Min, Tian, Leng, Du, Chang, Yang, Li, Shangguan, Yan, Dong, Han, Wang, Cosci and Wang2020). Furthermore, as a consequence of heightened anxiety due to the pandemic, along with the economic shock and stress related to quarantine, an increase in suicide is expected in Canada, the United States and possibly other countries (McIntyre and Lee, Reference McIntyre and Lee2020a, Reference McIntyre and Lee2020b).

Subthreshold depressive symptoms (i.e. not meeting minimum diagnostic threshold for a major depressive episode) are an important risk indicator for incident major depressive disorder (MDD). Persons with subthreshold depressive symptoms are approximately twice as likely to be diagnosed with MDD relative to those without (Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Roberto, Chatterji and Ayuso-Mateos2012; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Stockings, Harris, Doi, Page, Davidson and Barendregt2019). In the general population, the absolute risk of conversion to MDD from subthreshold depressive symptoms (excluded lifetime MDD) ranged from 0.012 to 0.096 per 100 person years (Cuijpers and Smit, Reference Cuijpers and Smit2004). A 13-year prospective study in communities indicated the mean age of first depressive episode in people with subthreshold depressive symptoms was 34 years, which was similar with the age onset in MDD (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Eaton, Gallo, Nestadt and Crum2000). It has been estimated that approximately 2.9%−9.9% of adults in primary care and 1.4%−17.2% of adults in community settings manifest subthreshold depressive symptoms (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Stockings, Harris, Doi, Page, Davidson and Barendregt2019).

Recent studies have raised concerns about populations that are more vulnerable to the detrimental mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, people with mental health conditions may be more substantially influenced by the emotional distress brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in relapses or worsening of pre-existing mental health condition(s) compared with the general population (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Chen and Xu2020). In addition, psychological response may change with fluctuations in the epidemic and clinical knowledge improvement. For example, a related longitudinal study investigating psychological adaptions during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak suggested that increasing knowledge and understanding of SARS could improve mental health outcomes (Su et al., Reference Su, Lien, Yang, Su, Wang, Tsai and Yin2007).

The primary aim of this longitudinal study is to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 in a subthreshold depressive symptom population. The secondary aim of this study is to explore potential predictors of mental health improvement to recommend feasible intervention under acute stress.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data in this study were derived from an ongoing longitudinal, population-based study for the early identification, treatment, prevention and management of depression and subthreshold depression (Depression Cohort in China [DCC] study, ChiCTR registry number 1900022145). Individuals were identified via a standardised community-based screening protocol for the detection of depression in two communities, 21 primary care centres, one general hospital and one specialised mental health hospital in Shenzhen, China. Participants aged 18–64 years meeting criteria for subthreshold depressive symptoms were enrolled between March 2019 and October 2019. Subthreshold depressive symptoms were operationalised as having a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) total score of ⩾ 5 without current or history of MDD. The follow-up period was 6 months. Exclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of MDD, severe psychiatric disorders (i.e. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective mental disorder, paranoid mental disorder, mental disorder caused by epilepsy, mental retardation) and/or alcohol or drug addiction disorder, (2) pregnant or perinatal women, (3) not being fluent in mandarin and (4) not having a plan to leave Shenzhen within 6 months. Psychiatric diagnoses were confirmed by trained psychiatrists using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria). The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Boards of all the participating centres, and all the participants gave written informed consent.

A total of 3715 people were screened, of which 2645 (71.2%) were from 21 primary care centres, 468 (12.6%) were from two communities, 368 (9.9%) were from a general hospital and 234 (6.3%) people were from a specialised mental health hospital. A total of 1722 participants were enrolled in the study between March 2019 and October 2019. Of the 1722 participants, 1506 (87.5%) participants completed the 6-month study; 216 participants were lost during follow-up (i.e. withdrew from study, n = 71; did not complete questionnaires, n = 29; unable to contact, n = 116). Of the 1506 participants with endpoint data, participants who completed the baseline and 6-month follow-up before the COVID-19 outbreak were classified into the ‘wave 1’ group (i.e. from March 2019 to January 2020) and participants who completed baseline before the COVID-19 outbreak but completed the 6-month follow-up during the COVID-19 outbreak were classified into ‘wave 2’ group (i.e. from August 2019 to April 2020).

BRIDGES integrate care

The DCC study used a Building Bridges to Integrate Care (BRIDGES) model, which used the Toronto-based BRIDGES model as a reference (Bhattacharyya et al., Reference Bhattacharyya, Schull, Shojania, Stergiopoulos, Naglie, Webster, Brandao, Mohammed, Christian, Hawker, Wilson and Levinson2016), and linked primary care centres, specialist hospitals and community care in accordance to the health system in Shenzhen. In this healthcare model, psychiatrists from specialist hospitals trained general practitioners (GPs) in primary care centres to identify, and provided treatment and education programmes for participants with subthreshold depressive symptoms. Project managers, who were public health doctors, from specialist hospitals supervised and ensured the quality administration of the intervention provided by the GPs. Both wave 1 cohort and wave 2 cohort received the same usual care, including (1) delivering project introduction brochures; (2) sending a short message service (SMS) monthly that provide mental health education (i.e. mental health stereotypes, depression treatments and stress arrangement); (3) telephone-based mental health consult every 6 months (i.e. mental health condition communication and updated information of psychiatric evaluation in study); (4) referral and face-to-face psychiatric evaluation for participants with PHQ-9 > 9 or for those with an active request to see a doctor.

Outcome and covariates

Depression and anxiety symptoms in the past 2 weeks were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9, Cronbach's α = 0.89) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7, Cronbach's α = 0.89), respectively (Kurt Kroenke and Williams, Reference Kurt Kroenke and Williams2001; Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Müller, Brähler, Schellberg, Herzog and Herzberg2008). The severity of depression and anxiety was divided into minimal, mild, moderate and severe based on a score of 0–4, 5–9, 10–14 (10–13 for anxiety) and 15–27 (14–21 for anxiety), respectively (Kurt Kroenke and Williams, Reference Kurt Kroenke and Williams2001; Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Müller, Brähler, Schellberg, Herzog and Herzberg2008). Participants with a score of PHQ-9 or GAD-7 ⩾ 5 were considered as probable depression or anxiety, respectively. Insomnia symptoms were assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI, Cronbach's α = 0.92), where participants were classified based on their score (i.e. group of none, subthreshold, moderate and severe of score 0–7, 8–14, 15–21 and 22–28, respectively) (Bastien et al., Reference Bastien, Vallières and Morin2001; Gagnon et al., Reference Gagnon, Belanger, Ivers and Morin2013). Participants with ISI > 7 was considered to have suspected insomnia.

To explore the fluctuations of the three main outcomes, as well as the COVID-19-related behaviours and perceived impacts during the outbreak, we separated wave 2 follow-up time into three intervals, which included the height of the pandemic (i.e. 7−13 February 2020 when the daily incidence of new COVID-19 cases climb to the peak and rigorous lockdown measures were implemented), the peak of the COVID-19 crisis (i.e. 14−27 February) and the remission plateau (i.e. 28 February−23 April). These three time intervals were defined as peak, post-peak and remission plateau, respectively. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the questionnaires were conducted face-to-face or online. During the COVID-19 outbreak, all of our questionnaires were conducted online.

We also assessed somatic symptoms, resilience and demographic characteristics (only at baseline) to explore the risk factors related to the main outcomes. The mean score for the seven pain-related items (items 2, 3, 9, 14, 19, 27 and 28) in the 28-item Somatic Symptoms Inventory (SSI, Cronbach's α = 0.80) was used to assess painful and non-painful somatic symptoms. Participants with mean scores for each item <2.2 in SSI were considered to be without pain (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Lu, Detke, Hudson, Iyengar and Demitrack2004). Resilience was assessed using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC, Cronbach's α = 0.91) (Yu and Zhang, Reference Yu and Zhang2007). As the cut-point score in the general population, we considered the mean score of CD-RISC below 80 as poor resilience (Connor and Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003).

Demographic characteristics were measured using self-report questionnaires, which included basic information, health status and behaviours. COVID-19-related behaviours and perceived impacts were also measured in wave 2 at the 6-month follow-up during the outbreak, including the number of days worrying about COVID-19 in the past week (i.e. 0–2 days, 3 days and above), perceived COVID-19 influence on current life (i.e. none or mild, moderate or severe), perceived COVID-19 influence on future life (i.e. none or mild, moderate or severe) and perceived risk of infection COVID-19 (i.e. none or low, moderate or high).

Statistical analysis

We estimated the proportion of depression, anxiety and insomnia symptoms at baseline and 6-month follow-up using the longitudinal surveys. For interpretative purposes, all outcomes and baseline characteristics were measured as categorical variables. In the univariate analysis, we identified the change between baseline and 6-month follow-up of severity in three main outcomes using the chi-squared test, as well as comparing the difference between wave 1 and 2 at baseline and follow-up. To explore the impact of COVID-19 and other potential factors on outcomes, we included all participants (n = 1506) in the binary logistic regression analysis to estimate their associations with probable depression, anxiety and suspected insomnia during the 6-month follow-up by adjusting for baseline severity of depression, anxiety and insomnia categories, respectively, presenting results as odds ratios. To examine the relationship between main outcomes in different time intervals of the COVID-19 outbreak and COVID-19-related behaviours, we selected participants in wave 2 and applied the chi-square trend test. All tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of p-values < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed on SPSS Statistic 25.0 (Property of IBM Corp.).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In our recruitment process, there were 36 people who were excluded due to the presence of a severe psychiatric illness in two waves (14 and 22 in wave 1 and 2, respectively). Of the 1506 participants, 726 participants completed the study in wave 1 and 780 participants completed the study in wave 2 (Table 1). Differences in baseline characteristics between participants who completed versus those who did not complete the study were not significant. Participants in wave 1 were older and more likely to be married when compared to participants in wave 2. Other baseline demographic characteristics were well balanced and similar between participants within the two waves. Furthermore, wave 2 participants had higher rates of chronic disease and smoking behaviour, as well as lower rate of exercise habit at baseline when compared to wave 1. There were no statistically significant differences in measures of depression, anxiety and insomnia at baseline between wave 1 and 2 (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline demographic information. All participants were enrolled in the 6-month study between March and October 2019

Abbreviation: wave 1: participants completed the baseline and 6-month follow-up before the COVID-19 outbreak (i.e. from March 2019 to January 2020); wave 2: participants completed the baseline before COVID-19 outbreak but 6-month follow-up during the COVID-19 outbreak (i.e. from August 2019 to April 2020).

Table 2. Changes in depression, anxiety and insomnia symptom severity scores from baseline to endpoint

Abbreviations: PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; SSI, Somatic Symptoms Inventory; CD-RISC, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. Wave 1, participants completed the baseline and 6-month follow-up before the COVID-19 outbreak (i.e. from March 2019 to January 2020); Wave 2, participants completed the baseline before COVID-19 outbreak but 6-month follow-up during the COVID-19 outbreak (i.e. from August 2019 to April 2020).

Outcomes were additionally compared between participants who completed the study before the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e. March 2019 to January 2020) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e. August 2019 to April 2020)

a Baseline comparison of wave 1 and 2.

b 6-month follow-up comparison of wave 1 and 2.

Comparison of main outcomes between baseline and 6-month follow-up

The unadjusted percentages of depression severity, anxiety and insomnia at baseline and 6-month follow-up were compared across all and separated waves in Table 2. There was 56% of participants with probable depression at baseline improved into the minimal group at 6 months. The prevalence rate of probable anxiety and suspected insomnia also increased by approximately 20% in both the minimal and none group, respectively. Additionally, the mean (s.d.) score of depression, anxiety and insomnia at the 6-month follow-up had a significant decrease compared with baseline, which were 4.7 (4.2) v. 8.1 (4.0), 3.5 (3.6) v. 5.6 (4.4) and 5.9 (5.5) v. 8.6 (6.2), respectively. However, in terms of the magnitude of remission, wave 2 showed a dramatic magnitude of remission compared to wave 1. Focusing on the severe group, depression accounted for the highest proportion among three main outcomes with 4.7% in wave 2 follow-up, compared with 2.6% in wave 1, followed by insomnia (2.8% and 1.2%, respectively). However, anxiety had a lower prevalence rate in the severe group of wave 2, as it accounted for a higher rate of 6.0% in the moderate group, compared with 3.3% in wave 1. The severity of the mild group took up largest proportion in depression, anxiety and insomnia in wave 2, which were 33.1%, 28.3% and 24.1%, respectively.

COVID-19 and other indicators related to the main outcomes in 6-month follow-up

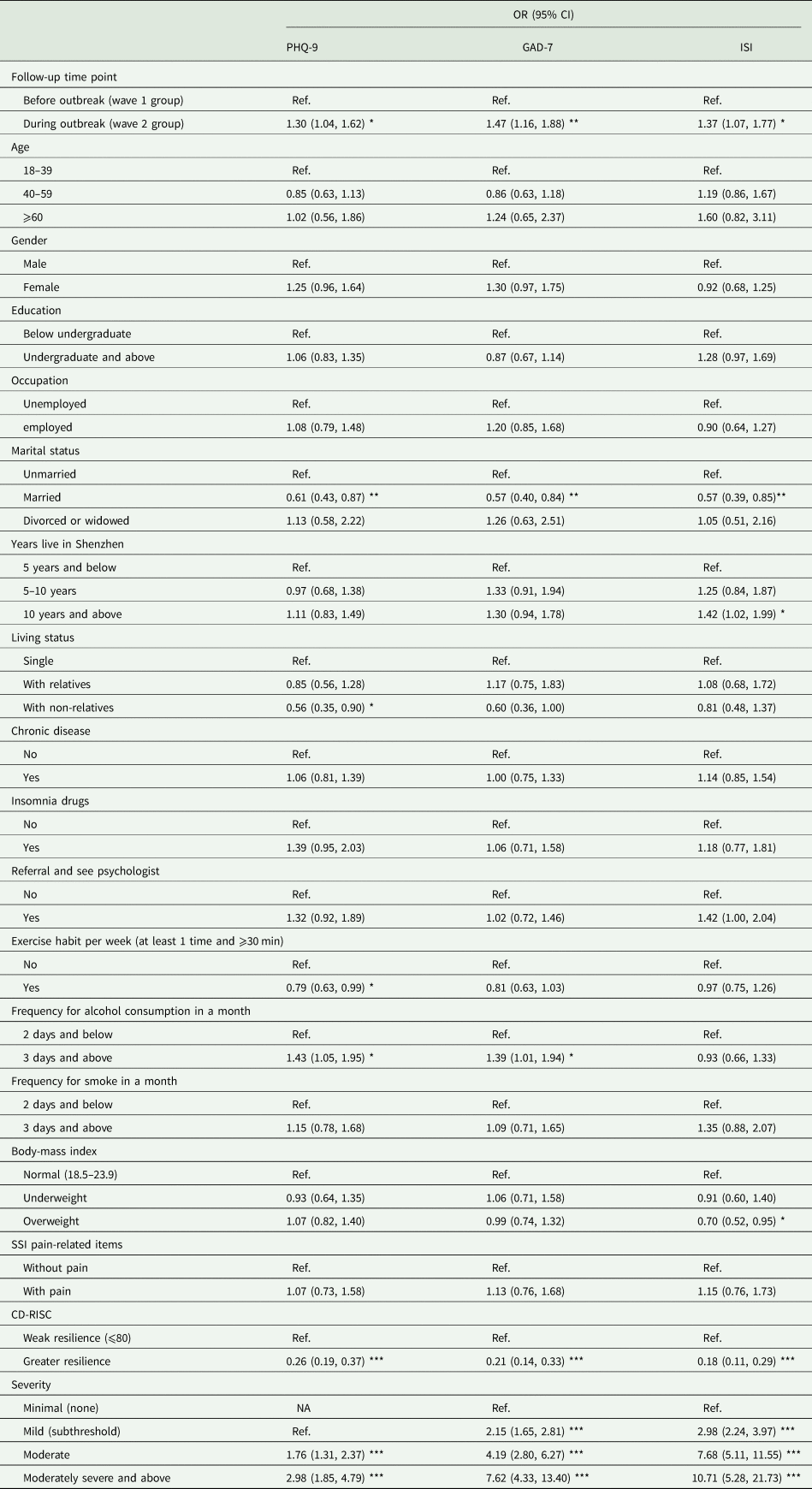

According to the severity change of mood scales, we examined whether the baseline characteristics had a favourable or unfavourable effect on depression, anxiety and insomnia. We defined 6-month outcomes into probable depression, probable anxiety and suspected insomnia. In Table 3, after adjusting for all indicators, participants who completed 6-month follow-up during COVID-19 outbreak was a risk factor for probable depression (OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.62), anxiety (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.16, 1.88) and suspected insomnia (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.77). Baseline severity of depression, anxiety and insomnia also showed a strong dose−response gradient with probable depression, anxiety and suspected insomnia, respectively. For somatic symptoms and mood resilience, SSI was not associated with all three main outcomes, whereas participants with better resilience (CD-RISC score >80) had a stronger beneficial effect on them.

Table 3. Moderators of probable depression, anxiety and insomnia

Abbreviations: PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; SSI, Somatic Symptoms Inventory; CD-RISC, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale.

*p-values < 0.05; **p-values < 0.01; ***p-values < 0.001.

In terms of the demographic indicators, being married contributed a beneficial effect to all of depression, anxiety and insomnia. Participants with alcohol consumption (i.e. 3 days and above in a month) were more vulnerable to probable depression (OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.95) and anxiety (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.94), whereas the association with suspected insomnia was not detected. In particular, exercising once per week and living with a non-relative were protective factors against depression. Having lived in Shenzhen for more than 10 years was associated with a greater risk for insomnia, whereas being overweight was protective against insomnia. Unadjusted and adjusted pooled estimates of probable depression, anxiety and suspected insomnia are available in the online supplementary materials.

Time-dependent change of main outcomes and behaviours during COVID-19 outbreak

To characterise the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on depression, anxiety and insomnia, we compared the proportion of participants meeting criteria for probable depression, anxiety and suspected insomnia at endpoint at the three different time intervals. Of the 780 participants who completed the study during the COVID-19 pandemic, 161 (20.6%), 367 (47.1%) and 252 (32.3%) were included in the peak, post-peak and remission plateau subgroups, respectively.

Baseline symptom severity did not differ between the three COVID-19-related subgroups (i.e. probable depression, χ 2 = 3.86, p = 0.43; probable anxiety, χ 2 = 2.01, p = 0.92; suspected insomnia, χ 2 = 7.29, p = 0.30). Figure 1 showed that probable depression and anxiety significantly changed across the follow-up time intervals. The highest rates of probable depression and anxiety were detected between 14 and 27 February 2020, which was after the peak of the newly diagnosed cases per day. From 28 February 2020 and onwards, the rate of probable depression and anxiety dropped to the lowest rate at 43% and 29%, respectively. However, the rate of suspected insomnia was not significantly different across the time process of COVID-19.

Fig. 1. Time-dependent change of probable depression, anxiety and suspected insomnia during COVID-19 outbreak. *p-values < 0.05. **p-values < 0.01.

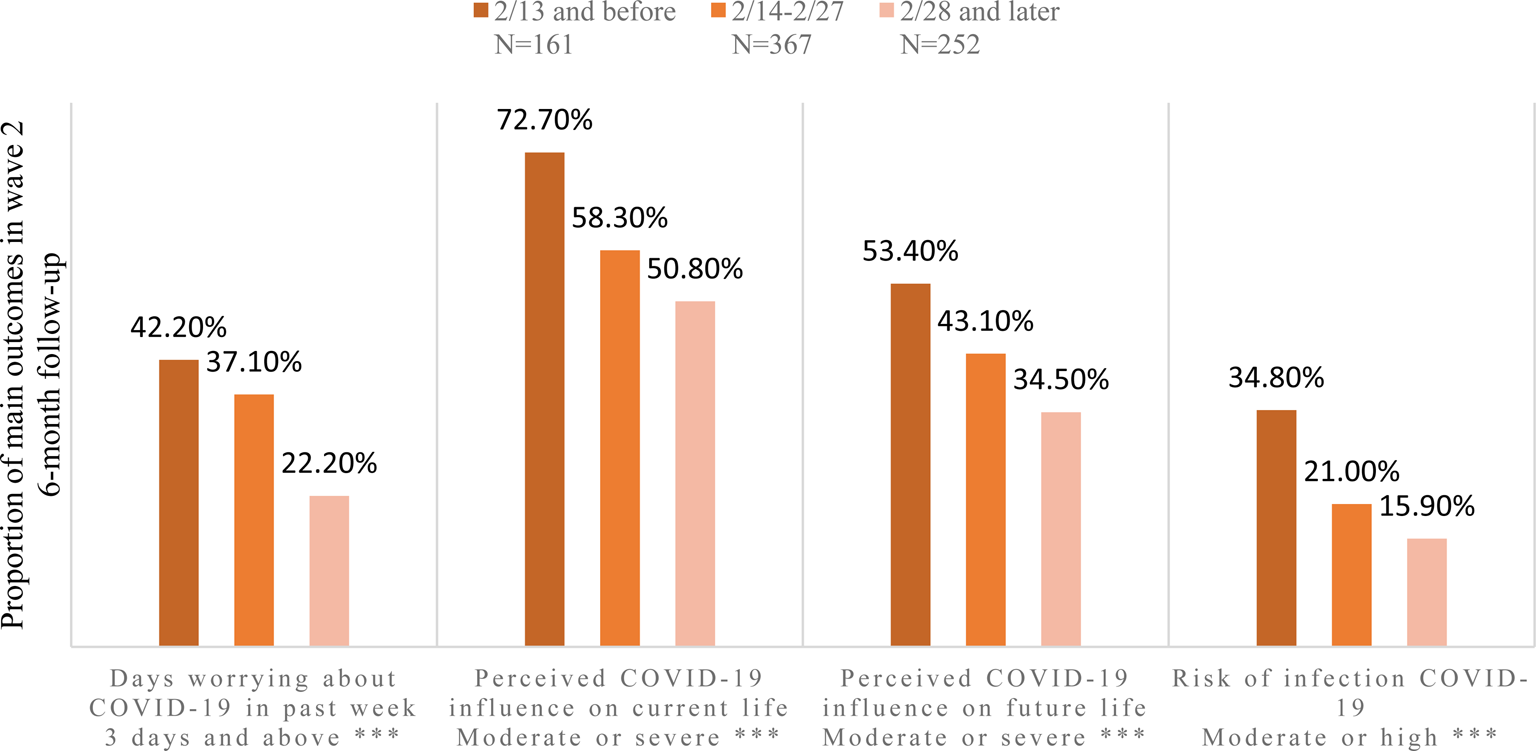

Individuals reporting greater symptoms of COVID-19-related distress, as operationalised by the number of days worried about COVID-19 in the past week (i.e. more than 3 days), perceived influence of COVID-19 on current and future life (i.e. moderate to severe) and perceived risk of infection (i.e. moderate to high), were significantly more likely, than those reporting fewer symptoms of distress, to have probable depression, anxiety and/or insomnia. Focusing on the COVID-19-related behaviours (Fig. 2), all four items demonstrated an inverse linear relationship with time process, with the Pearson correlation coefficient of −0.163 (p < 0.001), −0.154 (p < 0.001), −0.136 (p < 0.001) and −0.155 (p < 0.001) in days focus on COVID-19, perceived influence on current life, perceived influence on future life and perceived risk of COVID-19 infection, respectively. Different from the main outcomes change, the highest rate of behaviours was detected in the first time period of 13 February 2020 and before. Participants who perceived moderate or severe influence on current life accounted for the highest rate among all behaviour items.

Fig. 2. Time-dependent change of behaviours during COVID-19 outbreak. *p-values < 0.05. **p-values < 0.01. ***p-values < 0.001.

Discussion

Our prospective longitudinal study described the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subthreshold depressive symptoms. The general remission of depression, anxiety and insomnia had been detected from baseline to 6-month follow-up, whereas wave 2 participants who completed the follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic had significantly higher rates of probable depression, anxiety and insomnia relative to wave 1, after controlling for the sociodemographic characteristics, health status and behaviours and severity of baseline mental health outcomes. With the time process of COVID-19 outbreak in China, the highest rate of probable depression and anxiety had been found after the peak of newly diagnosed cases, and further decreased with the remission plateau. Similarly, the frequency and degree of COVID-19-related behaviours were also improving as the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic subsided.

COVID-19 and subthreshold depressive symptoms

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a profound effect on all aspects of society. We found that participants in our study had a relative higher proportion (47.8%) of probable depression during COVID-19 outbreak (wave 2), when compared to the general population in a previous study (30.3%) (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020a). A survey conducted in southwestern China, near Wuhan, also demonstrated a relative low prevalence of depression and anxiety with 8.3% and 14.6%, respectively (Lei et al., Reference Lei, Huang, Zhang, Yang, Yang and Xu2020). Nevertheless, health care workers shared similar rates of probable depression, anxiety and suspected insomnia with our study, which were 50.4%, 44.6% and 34.0%, respectively (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Ma, Wang, Cai, Hu, Wei, Wu, Du, Chen, Li, Tan, Kang, Yao, Huang, Wang, Wang, Liu and Hu2020). It could be hypothesised that the significant workload, as well as close contact with people who potentially have been infected by the virus, were also considered a susceptible population during the COVID-19 outbreak.

COVID-19 and stress

Epidemics act as a stressor during an outbreak and never affect all populations equally. For example, the individual effects of mental health stressors are moderated by personality and cognitive constructs. In our study, we found that resilience may play a more important protective role on depression, anxiety and insomnia. For example, it has been reported that the association between adverse childhood experiences and depression was stronger among individuals with low resilience compared to those with high resilience (Poole et al., Reference Poole, Dobson and Pusch2017). Psychological models suggest that individual differences in the strength of the personality or schema features determine how stressors will be interpreted. Stress appraisals that represent threats or depletion in the core areas of self-worth may portend depressive symptoms (Hammen, Reference Hammen2005). A separate study also demonstrated that the SL genotype in serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) gene appeared resilient to depression in terms of cortisol and recent stress (Ancelin et al., Reference Ancelin, Scali, Norton, Ritchie, Dupuy, Chaudieu and Ryan2017).

With respect to this large-scale pandemic and similar disasters, improving copying methods and mood resilience were an effective way to prevent mental health disorders. A randomised-controlled trial demonstrated that interventions targeting stress management, goal setting, cognitive reframing and meaning making significantly improved resilience and marginal effect to avoid depression in patients with cancer (Rosenberg et al., Reference Rosenberg, Bradford, Mccauley, Curtis, Wolfe, Baker and Yi-Frazier2018). Second, stressor content can lead to various mental health outcomes. Chronic and unpredictable stress (defined as stress for more than 12 months) is a stronger predictor of depressive symptoms than acute stressors. Interpersonal ‘loss’ event was unique significance for depression, which included bereavement, separations, endings or threats of separation (Hammen, Reference Hammen2005). To explore the psychological impact of COVID-19, we not only needed to consider the susceptible population, but also consider the different interpretations of stress in varying populations.

The temporality of the epidemic may lead to various outcomes vis-a-vis mental health conditions. In our study, probable depression and anxiety fluctuated with the COVID-19 outbreak curve, but, overall, the increasing rate of mental health outcomes were consistent with a study that showed higher average levels of symptoms (stress, anxiety and depression) after the nationwide state of alert and stay-at-home order (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., Reference Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Dosil-Santamaria, Picaza-Gorrochategui and Idoiaga-Mondragon2020). The study suggested that individuals have difficulty assimilating and processing the current crisis. The late stage reduction trend was similar to a meta-analysis which showed that depression, anxiety and insomnia symptoms in post-illness stage were lower than acute stage in SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) epidemic among the population (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Chesney, Oliver, Pollak, Mcguire, Fusar-Poli, Zandi, Lewis and David2020). This study suggested that if a COVID-19 infection follows a similar course to that of SARS or MERS, most patients should recover without experiencing mental illness. In general, an increasing trend of depression and anxiety may only be specific to a time interval of an acute stimulation. Some positive effects in terms of psychological regulation and personal coping styles were worth noting for mental health improvement. In addition, these mental health symptoms levels can be expected to increase further as confinement and isolation are extended, in addition to the adverse events induced by epidemic. Hence, it would be useful to further evaluate mental health conditions over time (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020).

Target interventions

In our study, there were other factors that drew our attention to their effects on the mental health condition in the 6-month follow-up. Regular exercise may attenuate the probability of developing depression compared with people with non-regular exercise habits (adjusted OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.63–0.99). The result was consistent with a meta-analysis which indicated that higher levels of physical activity were related to lower odds of developing depression (adjusted OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.79–0.88) (Schuch et al., Reference Schuch, Vancampfort, Firth, Rosenbaumr, Ward, Silva, Hallgren, Ponce De Leon, Dunn, Deslandes, Fleck, Carvalho and Stubbs2018). A randomised-controlled trial also demonstrated that the intervention of yoga plus regular care could significantly improve depression symptoms and score on CD-RISC, but not anxiety (Michael de Manincor et al., Reference Michael De Manincor, Smith, Barr, Schweickle, Donoghoe, Bourchier and Fahey2016). We also found that high frequency of alcohol consumption was harmful on probable depression and anxiety compared to low frequency.

The foregoing finding was in accordance with a study that indicated that hazardous drinking (a score⩾8 of Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test) was associated with a higher risk of depression than non-hazardous alcohol consumption (risk ratio = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.4, 2.4) (Gemes et al., Reference Gémes, Forsell, Janszky, Laszlo, Lundin, Ponce Dee, Mukamal and Moller2019). However, depending on the various definitions of alcohol consumption, depression is primarily related to drinking larger quantities per occasion and less related to volume and unrelated to drinking frequency; this effect is stronger for women than for men (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Massak, Demers and Rehm2007). Further studies need to identify the dose−response relationship between behaviours and mental health outcomes. Recommending a healthy lifestyle may afford a positive attitude to coping with adverse events.

Further research

Taken together, we draw the following views and provide some directions for further research: (1) more attention (e.g. resource allocation) could be paid to vulnerable and susceptible populations when an adverse event occurs. For example, expert resources including psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health hospital may target the people at severe risk actively (i.e. bereavement, COVID-19 infected/suspected cases and severe mental health symptoms). People with mild mental health symptoms could be monitored by social workers and receive psychoeducation from public media and service. It may be more cost-effective to allocate mental health resources in a reasonable way; (2) finding an appropriate way to improve mood resilience and coping methods under the stress may afford protections to prevent mental health disorders; (3) medical health workers may need to invest resources to mitigate the effects of a mental health outbreak during an epidemic and provided intervention promptly, as well as further attention on the following adverse events induced by epidemic; (4) mental health education may need to be provided, and may not only convey general information about mental health, but also recommend and conduct behaviours- and life-style-related intervention to prevent mental health problems.

Strengths and limitations

Major strengths of this study are its prospective design, the large representative community-based sample and the use of a clinically validated diagnostic interview to establish a wide range of mental disorders (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview). However, our study also has several methodological limitations that affect the inferences and interpretations of our data. First, we did not compare participants with mental health disorders to the general population in our study, wherein individuals without mental health disorders may have different reactions to mental health conditions on COVID-19. Second, our study only estimated the mental health impact until April 2020. Consequently, the effect of an economic recession, unemployment and concern about epidemic relapse after the epidemic may have a greater mental health impact on the general population and should be taken into consideration in future research.

In conclusion, COVID-19 plays an essential role to worsen mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety and insomnia. During the COVID-19 outbreak, mental health conditions and behaviours fluctuated with the epidemic time process, which may provide insight to mental health workers to conduct interventions to alleviate stress and anxiety. Furthermore, regular exercise and ways to improve resilience may be a feasible recommendation as a mental health prevention, whether or not an adverse event occurs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000044

Availability of data and materials

Data for the Depression Cohort in China are available through the Sun Yat-Sen University. Contact Professor Lu for access approval.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants of the study. The Depression Cohort in China (DCC) is conducted by the Sun Yat-Sen University and Shenzhen Nanshan Center for Chronic Disease Control in Shenzhen, China.

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81761128030).

Conflict of interest

All other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.