Introduction

The financial crisis that hit the global economy in 2008 led to the deepest recession since the 1930s (European Commission, 2009), possibly longer, wider and deeper than the Great Depression (Bambra et al., Reference Bambra, Garthwaite, Copeland, Barr, Smith, Hill and Bambra2016). The crisis had a varied impact across countries, resulting in a decline in gross domestic product (GDP), a rise in unemployment rates and severe fiscal pressure (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Figueras, Evetovits, Jowett, Mladovsky, Maresso, Cylus, Karanikolos and Kluge2014). Many countries adopted austerity policies, with substantial reductions in public spending affecting health and social care budgets, and many citizens faced growing insecurity and social exclusion (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Figueras, Evetovits, Jowett, Mladovsky, Maresso, Cylus, Karanikolos and Kluge2014).

Research on the social determinants of mental health has shown that health is shaped by social and economic conditions, as well as by health and welfare systems (World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2014). Economic crises may affect mental health either by increasing risk factors, such as unemployment, indebtedness and loss of socioeconomic status, or by weakening protective factors, such as job security and welfare protection programmes (Caldas de Almeida et al., Reference Caldas-de-Almeida, Cardoso, Antunes, Frasquilho, Silva, Neto, Santana, Ferrão and Saraceno2017). Indeed, recent reviews assessing the health consequences of economic crises have revealed a significant relationship between these periods and psychopathology including suicide, onset or exacerbation of mood and anxiety disorders, heavy drinking, and psychological distress (Frasquilho et al., Reference Frasquilho, Matos, Salonna, Guerreiro, Storti, Gaspar and Caldas-de-Almeida2016; Martin-Carrasco et al., Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec, González-Fraile, Bienkowski, Gómez-Beneyto, Dos Santos and Wasserman2016). These results would make expectable an increased search for mental health treatment. However, barriers to access to mental health care may be exacerbated during economic crises, due to changes in the availability (e.g., cuts in human resources) and affordability (e.g., out-of-pocket payments) of services (Wahlbeck and McDaid, Reference Wahlbeck and McDaid2012; Maresso et al., Reference Maresso, Mladovsky, Thomson, Sagan, Karanikolos, Richardson, Cylus, Evetovits, Jowett, Figueras and Kluge2015; Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Frasquilho, Cardoso, Pereira, Silva, Caldas-de-Almeida and Ferrão2017). Literature on how the use of mental health care varies in times of economic crisis is scarce, and recent reviews found mixed evidence (Zivin et al., Reference Zivin, Paczkowski and Galea2011; Cheung and Marriott, Reference Cheung and Marriott2015; Martin-Carrasco et al., Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec, González-Fraile, Bienkowski, Gómez-Beneyto, Dos Santos and Wasserman2016). Zivin et al. (Reference Zivin, Paczkowski and Galea2011) concluded that economic downturns might be associated with increased first admissions to mental health services. Cheung and Marriott (Reference Cheung and Marriott2015) found a decline in the use of mental health services in the USA, likely due to a lack of access to insurance, and an increase in the use of prescription medication. Martin-Carrasco et al. (Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec, González-Fraile, Bienkowski, Gómez-Beneyto, Dos Santos and Wasserman2016) concluded that the treatment gap increases in times of economic crisis, probably due to the lack of accessibility to services, the austerity measures, and the increased stigma towards people with mental illness. However, these reviews had some limitations: (a) only one of them followed the PRISMA guidelines (Martin-Carrasco et al., Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec, González-Fraile, Bienkowski, Gómez-Beneyto, Dos Santos and Wasserman2016); (b) one of the systematic reviews did not focus specifically on the use of mental health care (Martin-Carrasco et al., Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec, González-Fraile, Bienkowski, Gómez-Beneyto, Dos Santos and Wasserman2016); and (c) one did not include data from the 2008 Great Recession (Zivin et al., Reference Zivin, Paczkowski and Galea2011).

The aim of this study was to systematically review the available literature on the impact of economic crises on the use of mental health care, information that might contribute to the design of strategies, policies and programmes to promote equitable access to care in times of economic crisis.

Methods

Search strategy and selection of articles

The PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews were followed (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on 28 June 2017 (PROSPERO, registration No.: CRD42017069284). Comprehensive literature searches of MedLine (through Ovid and Pubmed), Scopus, Cochrane Database and Open Grey Repository databases were conducted, from inception to 20 June 2017 and last updated on 25 June 2018. Databases were searched separately by two reviewers (DMR and MS).

Three sets of keywords were combined in the search strategy: (1) economic crisis; (2) use of mental health; (3) mental health problems. Searches were piloted in Ovid and then adapted to run across the other databases (see Supplementary Table S1). The reference lists of the primary studies selected as well as recent reviews in the field were checked. In addition, we contacted expert authors to identify any additional articles.

Study selection was done in duplicate (DMR and MS), and a third reviewer participated where disagreements arose (GC) over the three phases. First, duplicate studies were deleted. Second, a selection of potentially relevant articles was made based on the title and abstract. Third, after reading the full text, a final selection was made. The inter-agreement between reviewers measured with the κ statistic was excellent (κ = 0.81; 95% CI 0.65–0.97).

The studies selected had to meet specific inclusion criteria (see Table 1). We focused on countries that faced crises since the 1990s as this would allow the inclusion of the available research on the impact of the main economic crises on health, namely the Post-Communist Depression in the early 1990s, the East Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, and the Great Recession in 2008. We selected only studies with a predominantly adult population, excluding those focusing on children and adolescents, as differences in psychopathology, clinical and social characteristics between children/adolescents and adults would make it difficult to draw conclusions. We excluded studies focusing on residential care, due to the fact that during economic crises the population living in residential care, although vulnerable, were likely to be less exposed to factors affecting an individual's search for mental health treatment (social determinants of mental health and barriers to treatment) compared with those residing in permanent private dwellings, and it would be difficult to make comparisons between the two populations. Only observational studies, including ecological, cross-sectional, case–control and longitudinal studies, were selected. We included all health settings which were accessed with mental health problems as the main complaint.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies included in the systematic review

Summary measures

The summary of measures included in the selected studies were relative risk (RR), adjusted relative risk (ARR), adjusted incidence rates (AIR) and incidence risk ratio (IRR).

Data synthesis

We developed a data extraction sheet, pilot tested it on three randomly selected studies that had been included and refined herein. The main characteristics of these studies were rigorously extracted by MS and verified by a second reviewer (DMR). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers. In the event of disagreement, a third reviewer (GC) was consulted.

For each study, information was collected about the author(s), year of publication, study country, setting, sample size, time period of crisis, study design, purpose of the study, outcome variable (indicator), procedure for data collection and main results (see Table 2).

Table 2. Details of studies included in this systematic review

AIR, adjusted incidence rates; CC, cross-correlation coefficient; PR, prevalence ratio; s.e., standard error.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Quality assessment was performed independently in duplicate (DMR and MS), and a third reviewer participated in cases of disagreement (GC). The quality of the studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (NHLBI, 2017), which assesses 14 items, rating quality as poor, fair or good.

Results

Search results

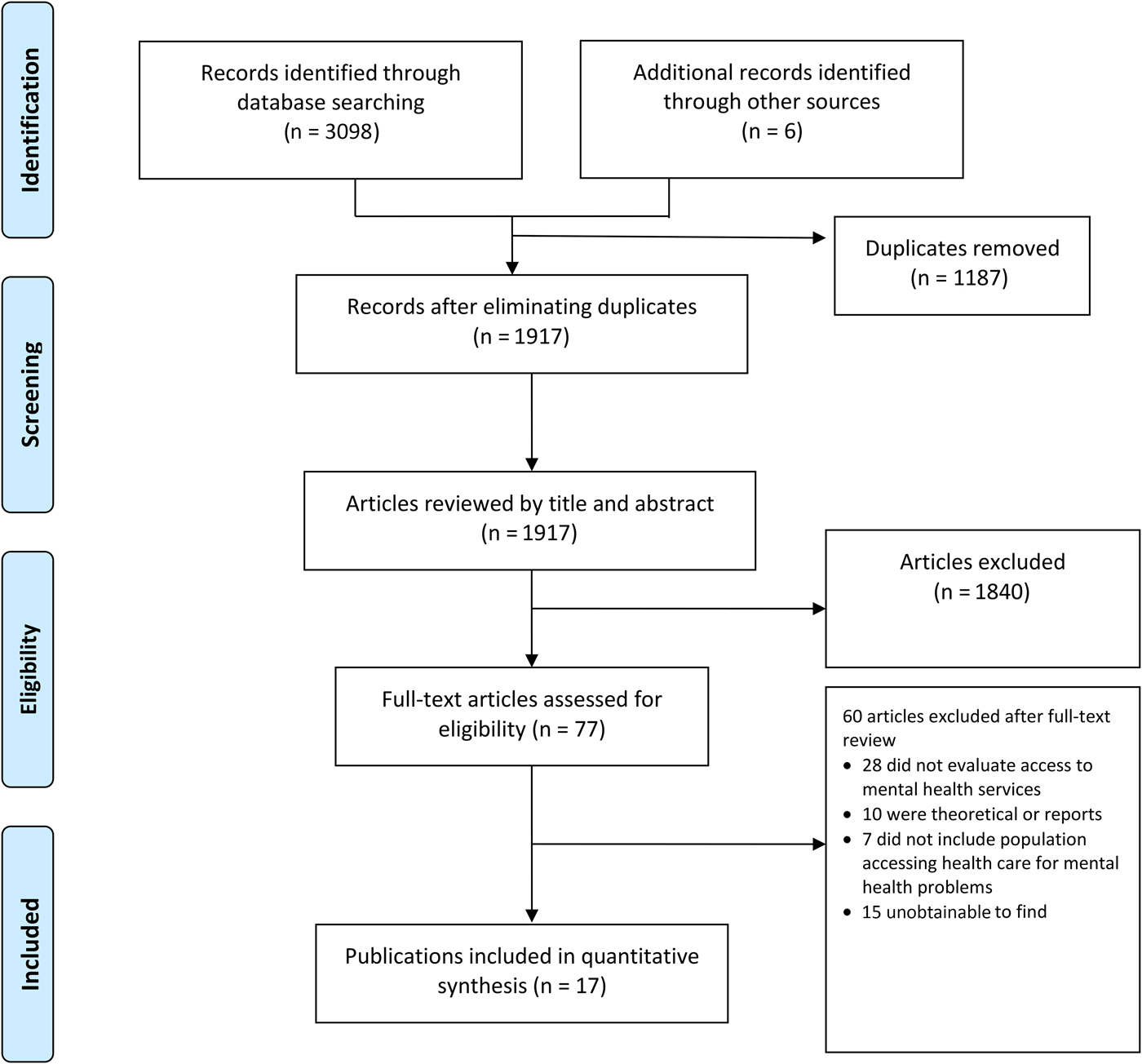

The search strategy produced 3098 potentially relevant studies (see Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram). Further six articles were identified from the references of the articles selected. Of these, 1187 were duplicates. Of those remaining, 1840 were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract. After reviewing the full text of the remaining articles, 60 were excluded for the following main reasons: 28 did not evaluate access or use of mental health services, ten were reports or theoretical articles, and seven did not include population accessing health care for mental health problems. Finally, 17 articles were selected.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of articles included and excluded after the systematic review.

The data of the included studies were extracted and summarised (see Table 2). Five were repeated cross-sectional studies, as well as four time series studies, three ecological studies, three cohorts, one panel study and one longitudinal study. Eleven studies employed national population samples and six employed regional samples. The studies were based on samples from European countries (58.82%), USA (29.41%), Australia (5.88%) and Republic of China (5.88%).

Study quality

The results of the quality assessment of the included studies are presented in Supplementary Table S2. All studies have an objective clearly stated and a study population prespecified. Only two studies provided a sample size justification (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016). Nine studies measured the exposure of interest prior to the outcome (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hebert, Hernandez, Batten, Lo, Lemon, Fihn and Liu2014; Bidargaddi et al., Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015; Gotsens et al., Reference Gotsens, Malmusi, Villarroel, Vives-Cases, Garcia-Subirats, Hernando and Borrell2015; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016; Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Han, Dowd, Cowell, Forman-Hoffman, Davies and Colpe2016; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016; Petrou, Reference Petrou2017). Seven studies did not provide adjustment for confounding variables (Ostamo and Lönnqvist, Reference Ostamo and Lönnqvist2001; Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014; Bidargaddi et al., Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015; Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda, Reference Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda2015; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016; Petrou, Reference Petrou2017).

Impact of the economic crisis on the use of health facilities

Use of general and specialised care for mental health problems

Periods of economic crisis appeared linked to an increase of general help seeking for mental health problems (Bidargaddi et al., Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda, Reference Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda2015), with mixed patterns for the use of specialised psychiatric care (Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hebert, Hernandez, Batten, Lo, Lemon, Fihn and Liu2014; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016; Petrou, Reference Petrou2017). Two studies conducted in European Union countries found that a significantly increased contact with a general practitioner for mental health problems occurred during the period of economic crisis (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda, Reference Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda2015), but a significantly decreased contact with a psychiatrist (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015) or no change in the use of specialist care occurred despite the higher proportion of referrals (Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda, Reference Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda2015). Bidargaddi et al. (Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015) found a higher number of visits to the medical emergency room for reasons of mental health during economic slow-down. Two studies in the USA found a significant increase in the utilisation of mental health services during the Great Recession (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hebert, Hernandez, Batten, Lo, Lemon, Fihn and Liu2014; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015), whereas two others found a significant decrease in the use of mental health services in this period (Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016), and one found no impact of the crisis on the utilisation rate (Petrou, Reference Petrou2017).

Hospitalisations for mental health problems

Several studies found an increase of hospital admissions for mental disorders during periods of economic crisis (Korkeila et al., Reference Korkeila, Lehtinen, Tuori and Helenius1998; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015; Bonnie Lee et al., Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin2017). In Finland (Korkeila et al., Reference Korkeila, Lehtinen, Tuori and Helenius1998), the increase of admissions was particularly significant in multiple readmissions among new inpatients (from 0.05 to 0.08, p < 0.001), and in the diagnostic group of mood disorders among first-timers (by 60%) and among patients with previous admissions (by 39%). In the USA (Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015), a marginally significant increase in the postrecession trend in inpatient utilisation compared with prerecession trend (b = 0.002; p = 0.078) was found. In Taiwan, Bonnie Lee et al. (Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin2017) found increased rates of hospitalisation for depressive illnesses. Specifically, the AIR of hospital admissions among the low-income group were ten times higher than those of the high-income group.

Use of health facilities due to suicide behaviour

The studies included found mixed results regarding the use of mental health care due to suicide behaviour (Ostamo and Lönnqvist, Reference Ostamo and Lönnqvist2001; Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017). Studies conducted in Nordic countries (Finland and Iceland) showed no overall increase in attendance rates due to suicide attempts and self-harm following economic crises (Ostamo and Lönnqvist, Reference Ostamo and Lönnqvist2001; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017). On the contrary, an increase in the use of health facilities for suicide attempt and self-harm after the onset of the 2008 crisis was found in other European countries (Spain and England) (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016), with authors proposing that the increase may be related to changes in unemployment.

Impact of the economic crisis on the use of prescription drugs

Different studies found an increase in the use of psychotropic drugs during the period of an economic crisis, including psychotropic medications to treat depressive and anxiety disorders (Gotsens et al., Reference Gotsens, Malmusi, Villarroel, Vives-Cases, Garcia-Subirats, Hernando and Borrell2015; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015; Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda, Reference Sicras-Mainar and Navarro-Artieda2015; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016). Gotsens et al. (Reference Gotsens, Malmusi, Villarroel, Vives-Cases, Garcia-Subirats, Hernando and Borrell2015) compared the use of psychotropic drugs between natives and immigrants who arrived in Spain before 2006 and found that the increase in the use of psychotropic drugs was higher among immigrant men.

Impact of macroeconomic indicators on the use of mental health care

Several articles included in this review found that unemployment rates were associated with changes in help-seeking behaviour for mental health problems (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hebert, Hernandez, Batten, Lo, Lemon, Fihn and Liu2014; Bidargaddi et al., Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015; Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Han, Dowd, Cowell, Forman-Hoffman, Davies and Colpe2016; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017). The likelihood of men contacting a general practitioner for mental health problems was found to be higher in countries experiencing an increase in the unemployment rate (OR = 1.031, 95% CI) (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015). Studies in the USA found significant associations between higher local unemployment and increased outpatient visits, use of opiates and sleep aids (Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015), as well as increased outpatient utilisation among veterans exempt from copayments (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hebert, Hernandez, Batten, Lo, Lemon, Fihn and Liu2014). However, a third study in the USA (Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Han, Dowd, Cowell, Forman-Hoffman, Davies and Colpe2016) found that individuals who resided in counties with higher unemployment rates were less likely to use mental health services compared with individuals who resided in counties with the lowest unemployment rates (ARR = 0.58, 0.62 and 0.71). Similarly, in Spain, the increase in the unemployment rate was associated with a clear decrease in mental health demand (Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014). Unemployment rates were also associated with the use of mental health care due to suicide attempts in men, accounting for almost half of the cases during the five initial years of the crisis in Spain (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014). However, Ásgeirsdóttir et al. (Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017) found that a 1% increase in unemployment rate was significantly associated with reduced attendance rates due to suicide attempts among men in Iceland (RR = 0.84; 0.76–0.93), but not among women.

Buffel et al. (Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015) found that, in countries with a decline in the GDP growth rate, employed men were less likely to contact a psychiatrist (OR = 0.966, 95% CI) compared with those in countries with an increase in the GDP growth rate, while Iglesias García et al. (Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014) found that GDP increase was strongly associated with an increased demand for mental health care.

Finally, Dunlap et al. (Reference Dunlap, Han, Dowd, Cowell, Forman-Hoffman, Davies and Colpe2016) found that individuals who resided in states with higher rates of serious mortgage delinquency were less likely to use mental health services (ARR = 0.54, 0.52 and 0.73, respectively).

Impact of individual indicators on the use of mental health care

Several studies included showed a higher utilisation of mental health care by women (such as access to outpatient visits, emergency department, prescription drugs and hospitalisation) compared with men during the crisis (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016; Bonnie Lee et al., Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin2017). Regarding the risk of attendance of health facilities due to suicidal behaviour, Ostamo and Lönnqvist (Reference Ostamo and Lönnqvist2001) showed that there was a convergence of rates between genders, with the men's rates decreasing 15% (trend test χ 2 = 10.45, p ⩽ 0.001) and the women's rates increasing 8% (trend test χ 2 = 2.55, p = 0.11). Other studies showed that socioeconomic factors were more strongly associated with suicidal behaviour care in men than in women (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017).

Two studies found that adults aged 35–54 years were the risk group for the use of care due to suicidal behaviour (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016).

Bonnie Lee et al. (Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin2017) suggested low income to be a risk factor for hospitalisation for depressive disorders.

Gotsens et al. (Reference Gotsens, Malmusi, Villarroel, Vives-Cases, Garcia-Subirats, Hernando and Borrell2015) found that, in Spain, the 2008 economic crisis may have had a worse impact on the health status of immigrants, as shown by the loss of the ‘healthy immigrant effect’ and the equalisation of the previously lower use of psychotropic drugs among immigrants compared with natives. Chen and Dagher (Reference Chen and Dagher2016) found that ethnic minorities presented lower rates of health care use during the 2008 Great Recession. Specifically, compared with white women, African American women had significantly fewer physician visits (IRR = 0.71, p = 0.01), and Latinas and African American women used significantly fewer prescription drugs (IRR = 0.75, p < 0.001; IRR = 0.71, p < 0.001). Compared with white men, Latino men had significantly lower rates of physician visits (IRR = 0.72, p < 0.05), and lower rates of prescription drug utilisation (IRR = 0.72, p < 0.001). Burgard and Hawkins (Reference Burgard and Hawkins2014) found that levels of foregone mental health care rose in the Great Recession of 2007–2009, but that disparities between ethnic groups in foregone mental care were stable during the recession.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to specifically study the impact of the economic crisis on the utilisation of mental health care following PRISMA guidelines. This study is relevant for systematising the scarce literature available, and for highlighting the risk of a growing treatment gap, particularly among the most vulnerable groups.

Our results suggest an increase of general help-seeking behaviour for mental health problems, with more contradictory results in relation to the use of specialised psychiatric care. There may be several explanations for these findings. First, in times of economic crisis, more accessible and affordable general health care might be the preferred pathway to care, with the subsequent increase in unmet need for specialised care (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015). In these periods, reduced mental health budgets may decrease availability of mental health services and/or they may be unaffordable because of the reduction of households’ disposable income, lack of health insurance coverage or the introduction of copayment in the public health care sector (Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Han, Dowd, Cowell, Forman-Hoffman, Davies and Colpe2016). Second, decreased motivation to demand specialised care may be due to possible negative consequences, such as fear of losing a job due to work disability or treatment stigma (Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014). Lastly, the adverse social circumstances that occur in periods of economic crisis might cause health expectations to decrease and induce more personal efforts to be taken on to achieve these expectations (Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014).

The review conducted by Martin-Carrasco et al. (Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec, González-Fraile, Bienkowski, Gómez-Beneyto, Dos Santos and Wasserman2016) had already described an increase in the treatment gap during times of economic crisis, pointing out the lack of accessibility to services, the austerity measures and the increased stigma as probable explanations.

Our review found different trends in relation to the use of mental health care due to suicide behaviour between the Nordic countries and other European countries. Possible factors explaining these findings might be Nordic countries’ relatively high levels of social capital and strong welfare systems, possibly mitigating the adverse consequences of unemployment on suicidal outcomes (Ostamo and Lönnqvist, Reference Ostamo and Lönnqvist2001; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017).

Our results also suggest that economic crises might be associated with a higher use of prescription drugs and an increase in hospital admissions for mental disorders, as had been found in previous reviews (Zivin et al., Reference Zivin, Paczkowski and Galea2011; Cheung and Marriott, Reference Cheung and Marriott2015).

The results provide information on the patterns of demand for care of different groups defined by an axis of inequality during economic crises. The groups of people most susceptible to the effects of crises were not consistently those that most accessed mental health care (Burgard and Hawkins, Reference Burgard and Hawkins2014; Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Iglesias García et al., Reference Iglesias García, Sáiz Martinez, García-Portilla González, Bousoño García, Jiménez Treviño, Sánchez Lasheras and Bobes2014; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Hebert, Hernandez, Batten, Lo, Lemon, Fihn and Liu2014; Bidargaddi et al., Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Gotsens et al., Reference Gotsens, Malmusi, Villarroel, Vives-Cases, Garcia-Subirats, Hernando and Borrell2015; Modrek et al., Reference Modrek, Hamad and Cullen2015; Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Han, Dowd, Cowell, Forman-Hoffman, Davies and Colpe2016; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017; Bonnie Lee et al., Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin2017). Mental health care utilisation patterns depend on the recognition that help is needed (Andrade et al., Reference Andrade, Viana, Tófoli and Wang2008; Mojtabai et al., Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and Mechanic2002), on structural factors including financial costs (Mojtabai, Reference Mojtabai2009), and availability of services (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Miranda, Bauer, Bruce, Durham, Escobar, Ford, Gonzalez, Hoagwood, Horwitz, Lawson, Lewis, McGuire, Pincus, Scheffler, Smith and Unützer2002; Saxena et al., Reference Saxena, Sharan and Saraceno2003), and on attitudinal factors (Sareen et al., Reference Sareen, Jagdeo, Cox, Clara, ten Have, Belik, de Graaf and Stein2007; Mojtabai, Reference Mojtabai2010). These factors might change during economic crises and affect differently the various socioeconomic groups, possibly exacerbating systemic problems in access to care and widening social inequalities in mental health. The reasons for the increased treatment gap among vulnerable groups might include a disproportionate worsening of socioeconomic conditions, the impact of austerity measures, and subsequent reduced available income, lack of social protection and a reduction in available health care, but also worse perceived need for care, reluctance to seek services and/or cultural or linguistic barriers.

In the studies included, during periods of crisis, women used mental health care more frequently than men (Bidargaddi et al., Reference Bidargaddi, Bastiampillai, Schrader, Adams, Piantadosi, Strobel, Tucker and Allison2015; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, van de Straat and Bracke2015; Chen and Dagher, Reference Chen and Dagher2016; Bonnie Lee et al., Reference Bonnie Lee, Liao and Lin2017). This might reflect women's relatively worse mental health status and higher need for care or gender differences in healthcare-seeking behaviour. Reasons for gender differences in healthcare-seeking behaviour could be greater stigma among men, a greater ability of women to identify their mental health problems or differences in health insurance coverage. Some of the studies reviewed suggest that socioeconomic factors may be more strongly associated with suicidal behaviour in men than in women (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016; Ásgeirsdóttir et al., Reference Ásgeirsdóttir, Ásgeirsdóttir, Nyberg, Thorsteinsdottir, Mogensen, Matthíasson, Lund, Valdimarsdóttir and Hauksdóttir2017). One possible explanation to this finding is that men are subjected to more pressure from their working role and relative expectations of socioeconomic success, thereby sensitised to unmet expectations. Related to this, mild-adulthood seemed to be the most consistent risk group for the use of care due to suicidal behaviour (Córdoba-Doña et al., Reference Córdoba-Doña, San Sebastián, Escolar-Pujolar, Martínez-Faure and Gustafsson2014; Hawton et al., Reference Hawton, Bergen, Geulayov, Waters, Ness, Cooper and Kapur2016). This finding could be attributed to the fact that it is a period of pressure to the main earners, and during which financial crisis-related events most frequently occur.

Policy implications

The results of this systematic review highlight the need for health services to be particularly attentive and responsive to changes in patients’ socioeconomic status, especially to the needs of the most vulnerable groups.

Models of care that are closer to the population, that facilitate the early identification of mental health problems and the implementation of integrated interventions, and that have a focus on prevention of mental health problems and disorders are particularly useful.

It is crucial to maintain universal, accessible and affordable health care of good quality to avoid increasing the treatment gap.

Additionally, reforms of social welfare to maintain or strengthen safety nets and interventions across several sectors beyond the mental health sector are fundamental to minimise increasing social inequalities in mental health during economic crises.

Strengths and limitations

This review provides updated evidence about the impact of economic crises on the use of mental health care, and it is the first systematic review following the PRISMA statement in this field.

The results give us some information on the patterns of demand for care of different socioeconomic groups during these periods, and we propose some insights for these findings.

However, results should be taken with caution due to several aspects.

First, studies from some of the most severely affected countries by economic crises were not available, and this low representation of geographical and health systems limits the interpretation of our results. The scarce variety of a study's origin may reflect different levels of cross-country research or a publication bias, due to financial constraints, methodological difficulties or language barriers. It would be highly beneficial if this gap in the existing literature could be improved.

Second, the diversified designs of the included studies make it difficult to derive more homogeneous and robust conclusions, and to ascertain causality. Future studies should combine both aggregate-level and individual-level research, and longitudinal studies are needed. Measurement error may have occurred for some of the indicators. Service indicators are dependent on the nature and structure of the services, many are clinical and not based on standardised interviews and have limitations such as potential variations in the registry. Most of the studies reported that, during the period studied, there was no variation in the organisation of mental health services or registration process, in addition to those resulting from the austerity measures. Due to the special features of economic crises in each country, the specific national welfare and health systems and the countries’ policies adopted to deal with the crisis, external validity may be limited, and further research is needed to confirm the results obtained.

Third, the literature included results linked to different economic crises worldwide. Different types of economic crises will influence the length, depth and effects of the recession.

Conclusions

Research is scarce on the impact of economic crises on the use of mental health care, and methodologies used in these papers were prone to substantial bias. However, the evidence suggests that periods of economic crisis might be linked to an increase of demand for care at the general care level, an increase of hospital admissions for mental disorders and a significant higher use of prescription drugs, with more conflicting results in the use of specialised psychiatric care.

Other crises will occur in the future, and more empirical and long-term studies are needed in order to adapt mental health care systems to the needs of the populations, especially in times of economic crisis.

Conflict of interest

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data regarding the process of screening and selection of the articles included in this systematic review are available in an online Supplementary material.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000641