No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

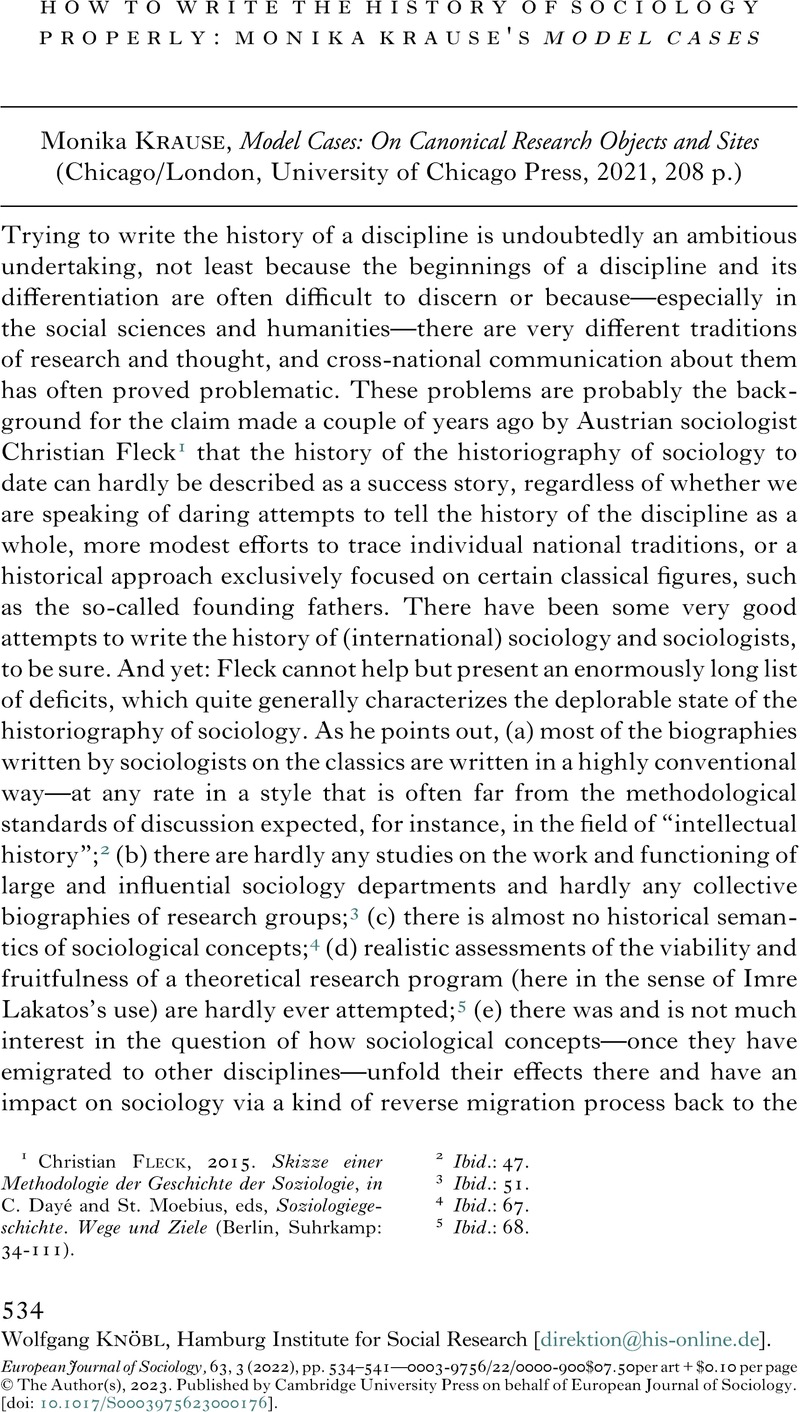

How to Write the History of Sociology Properly: Monika Krause’s Model Cases - Monika Krause, Model Cases: On Canonical Research Objects and Sites (Chicago/London, University of Chicago Press, 2021, 208 p.)

Review products

Monika Krause, Model Cases: On Canonical Research Objects and Sites (Chicago/London, University of Chicago Press, 2021, 208 p.)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 February 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Book Review

- Information

- European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie , Volume 63 , Issue 3 , December 2022 , pp. 534 - 541

- Copyright

- © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of European Journal of Sociology

References

1 Christian Fleck, 2015. Skizze einer Methodologie der Geschichte der Soziologie, in C. Dayé and St. Moebius, eds, Soziologiegeschichte. Wege und Ziele (Berlin, Suhrkamp: 34-111).

2 Ibid.: 47.

3 Ibid.: 51.

4 Ibid.: 67.

5 Ibid.: 68.

6 Ibid.: 71.

7 Ibid.: 83.

8 Ibid.: 85.