Introduction

The goal of this paper is to theorize the consequences of neoliberalism for social policy. One of the main challenges in this task is that scholars disagree on the definition of neoliberalism [for overviews of the literature and attempts to provide coherent definitions, see e.g. Larner Reference Larner2000; Mudge Reference Mudge2008; Mirowski Reference Mirowski, Mirowski and Plehwe2009; Steger and Roy Reference Steger Manfred and Roy2010; Wacquant Reference Wacquant2012; Dean Reference Dean2014; Flew Reference Flew2014; Hardin Reference Hardin2014; Cahill and Konings Reference Cahill and Konings2017; Byrne Reference Byrne2017; Fine and Saad-Filho Reference Fine and Saad-Filho2017]. For some scholars the concept of neoliberalism has come to be used in so many contradictory ways that it has lost its analytical value [Venugopal Reference Venugopal2015]. In contrast, in this paper I argue that neoliberalism may still help scholars to make sense of broad principles in social policy theory and practice, which are distinct from the Keynesian social-democratic model of social citizenship. Precisely like the latter, neoliberalism too provides a theoretical abstraction that encompasses a wide range of different historically realized social formations. Thus, theorizing “neoliberal social policy” requires a certain degree of generalization. Hence, in this paper I am more concerned—following Streeck [Reference Streeck2012: 21-22]—with differences in capitalism over time rather than between capitalisms in space, with historical evolutions rather than with cross-country comparisons, and with the “commonalities” among contemporary varieties of capitalism.

My purpose is not to propose a comprehensive and exhaustive definition of neoliberalism and I do not aim to resolve the epistemological and ontological tensions between the different theoretical and empirical approaches to the study of neoliberalism. More modestly, my goal is—in the same spirit as Springer [Reference Springer2012]—to at least partially reconcile different interpretations of neoliberalism that may appear incompatible, focusing especially on those studies in the tradition of political economy that define neoliberalism as a hegemonic ideology, on one hand, and those studies influenced by Michel Foucault’s interpretation of neoliberalism as governmentality, on the other.

When interpreted as an ideology, neoliberalism is a hegemonic project of the capitalist classes aimed at reasserting their power after the social democratic compromise that characterized the post-war welfare state [Duménil and Lévy Reference Duménil and Lévy2004; Harvey Reference Harvey2005]. Within political economy, neoliberalism is also associated with a “mode of regulation,” whereby capital accumulation is sustained in the context of a post-Fordist and globalized economy, and thus the transformation of the welfare state into a “competition state” [Cerny Reference Cerny Philip1997; Jessop Reference Jessop1993]; with a shift in the balance of class power towards capital at the expense of labor [e.g. Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2011]; with the rise in power of giant (multinational) corporations [Crouch Reference Crouch2011]; and with the financialization of capitalism and society as a whole [Fine and Saad-Filho Reference Fine and Saad-Filho2017]. In contrast, following Foucault [2008], in the governmentality literature, neoliberalism is associated with a political rationality and with specific “technologies” that govern both institutions—including states—and individuals according to market rules, with a view to maximizing economic efficiency [e.g. Burchell Reference Burchell1993; Dardot and Laval Reference Dardot and Laval2014; Dean Reference Dean2002; Donzelot Reference Donzelot2008; Lemke Reference Lemke2001; Rose Reference Rose1993].

In studying the nature of “neoliberal social policy,” this paper tries partly to reconcile these different perspectives, focusing on the “economization of the social” as a central characteristic of neoliberalism. For Foucault [2008] economization is a defining aspect of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism extends the economic logic to non-economic domains, scrutinizing all public actions in terms of efficiency: the cost-benefit logic is used to evaluate all social programs, judging government action in strictly economic terms [Foucault Reference Foucault2008: 246-247]. Within (Marxist and neo-Marxist) political economy, there is a long tradition that emphasizes commodification as a central characteristic of capitalism. For example, drawing on various thinkers, such as Marx, Polanyi and Rosa Luxemburg, Wolfgang Streeck [Reference Streeck2010: 154-155; 2012: 2-5] recently argued that it is inherent in capitalism to penetrate—and take possession of—previously non-capitalist social relations governed by other logics (such as authority and reciprocity), subjecting them to the economic logic of profit maximization. Capitalism is dependent on expansion and thus always needs to conquer new “lands” (imperialism)—also in a figurative sense: new social domains—in order to maintain and increase capital’s profitability. In this context, neoliberalism reinforces economization processes already inherent in capitalism: the “neoliberal project” involves the “corporatization, commodification, and privatization of hitherto public assets” with a view to opening up “new fields for capital accumulation in domains hitherto regarded off-limits to the calculus of profitability,” such as “public utilities of all kinds (water, telecommunications, transportation), social welfare provision (social housing, education, health care, pensions), public institutions (universities, research laboratories, prisons),” and so on [Harvey Reference Harvey2005: 160]. In turn, commodification not only enhances profit opportunities for capitalists but also extends the economic logic to spheres that previously followed other logics, such as that of social rights.

From this perspective, economization constitutes a possible “bridge” between (neo‑)Marxist-structuralist and Foucauldian-post-structuralist accounts of neoliberalism. Structuralist versions emphasize the changing exigencies of the economic system (and of capital accumulation) in generating economization pressures, thereby pointing also to the power of the capitalist class in shaping these processes. In contrast, post-structuralist interpretations emphasize the spreading of economic logic as a tool of technocratic governance, which produces specific subjectivities and state forms, and power is more diffused and “internalized” by self-disciplined actors.

This difference is important, but following Springer [Reference Springer2012: 140] I argue that, “notwithstanding the epistemological and ontological differences, Marxian political economy and poststructuralism are not necessarily incommensurable.” In particular, what matters for this paper is that scholars working within both traditions emphasize processes of economization as a central aspect of neoliberalism. Thus, while neo-Marxist and Foucauldian interpretations of neoliberalism are in many respects scarcely reconcilable, through economization the two definitions can work in tandem: because economization makes it possible to reframe social objects as commodities, it also potentially increases opportunities for profit-making—and this is what capitalists look for. In other words, economization can be interpreted both as a form of governmental rationality and as a way of extending the opportunities for capitalist accumulation to previously uncommodified areas.

Moreover, concerning social policy more specifically, I argue that economization can be linked not only to austerity and welfare retrenchment but also to attempts to make neoliberalism more “social” and “inclusive.” In this context, the paper’s key argument is somewhat paradoxical: the deeper and more intense economization processes are, the more it becomes possible to realize social goals within neoliberalism.

The paper is structured as follows. The first section offers some preliminary considerations on the economization of the social. The second section highlights how economization relates to capitalism and to the emergence of welfare politics. The third section clarifies the link between economization, neoliberalism, and welfare retrenchment. Sections four to eight focus on the link between economization and the “new welfare state” centered on “social investment” and highlight the paradoxes and problems of economization. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main arguments.

Preliminary Clarifications on the “Economization of The Social”

Before going into the details of my argument, let me clarify what I mean by “economization of the social.” First of all, in using this phrase I am not suggesting a dichotomous relationship between the economy and society, whereby the economy would be somehow apart from society. Indeed, the economy is always part of society, as economic relations are social relations. At its most general-abstract level, economization can be defined as “the processes that constitute the behaviors, organizations, institutions and, more generally, the objects in a particular society” as “economic” [Çalışkan and Callon Reference Çalışkan and Callon2009: 370]. Hence, in this constructivist perspective, “the economy is an achievement rather than a starting point or a pre-existing reality” [Ibid.: 370]. This implies not only that what counts as “economic” is often controversial and varies in different historical and social contexts, but also that the economy can be organized in very different ways. Even “marketization”—as one particular modality of economization—encompasses a wide diversity of forms, ranging from capitalist to non-capitalist markets and from formal to informal markets [Çalışkan and Callon Reference Çalışkan and Callon2010: 4]. Similarly, there is not one universal “economic rationale,” but many different economic logics. This is why Çalışkan and Callon [2009: 387] reject the “a priori existence of regimes, systems or spheres”: while distinct “modes of valuation” do exist, these “are not embedded in pre-existing regimes or bounded systems.”

This general approach to economization is useful to situate—both socially and historically—those more specific processes of economization that are inherent in neoliberalism. Indeed, as already mentioned, the scholarship on neoliberalism tends to equate economization with: a) the extension of economic logic (understood as utilitarian cost-benefit logic) to non-economic areas (in the Foucauldian literature), and b) the promotion of profit-oriented commodification, marketization and privatization (in the Marxist literature). Thus, the literature on neoliberalism suggests the existence of both an “economic system” and an economic rationale/logic inherent in it. The implicit argument is that while there is nothing natural in the fact that profit-maximization represents the logic of the economic system (i.e. there are other possible principles and norms that could govern economic life) a capitalist economy is an economy in which profit maximization represents the dominant—even if empirically never exclusiveFootnote 1—principle for organizing the economy. On this basis, I use here the concept of economization in a more specific way than the one proposed by Çalışkan and Callon. In particular, referring to the Foucauldian and (neo-)Marxist interpretations of neoliberalism, I conceive economization as the extension and/or deepening of the utilitarian logic of efficiency-enhancement and of the capitalist rationale of profit-maximization in society.

Turning to the concept of the “social,” I use it here mainly to indicate the domain of social policy and the welfare state. Crucially, while in the reminder of this paper I am concerned with highlighting how neoliberalism promotes a restrictive view of the “social,” this focus should not be misunderstood as an idealization of the latter. Hence, pointing to the problems associated with economization should not be confused with a nostalgic view of either pre-capitalist social formations or post-war social democracy, that is, of solidarity in general and/or of its concrete manifestations in Keynesian welfare states. Concerning the “social” in general, Fontaine [Reference Fontaine2014] has convincingly shown that non-market social relationships based on the moral logics of gift, reciprocity and solidarity may actually hide and reinforce severe power asymmetries, stabilizing social hierarchies that reject equality and democracy. In this context, the emancipatory potential of the market should not be underestimated. With regard to post-war welfare states, Fraser [Reference Fraser2013: 127-128] similarly notes that they often disempowered their beneficiaries, turning “citizens” into “clients,” and that protections premised on “androcentric views of ‘work’ and ‘contribution’” implied that “what was protected was less ‘society’ per se than male domination.”

Beyond these two preliminary considerations—i.e. that my argument refers to a specific form of economization and that it does not turn a blind eye to the problems associated with the “social”—I want to emphasize a final point here, which refers to the non-linear, variegated, and potentially ambivalent nature of economization [Griffen and Panofsky Reference Griffen and Panofsky2021]. Building on Hirschman and Berman [Reference Hirschman and Berman2014], Griffen and Panofsky [2021] usefully distinguish two modes of economization. The first consists of the application of an “economic style of reasoning” to domains that were not previously framed in economic terms. The second involves more concrete processes “by which things are transformed into economic objects that can be measured, compared, evaluated and manipulated in economic terms” [Ibid.: 518, emphasis in the original]. These two types of economization do not necessarily go hand in hand and there can be tensions between them (as in the empirical case studied by Griffen and Panofsky). Indeed, “the pathways of economization are linked to interests and aims of competing social actors” [Griffen and Panofsky Reference Griffen and Panofsky2021: 519]. In this paper I focus on both types of economization, exploring how the economic way of thinking about the social is translated into more concrete policy instruments.

Economization, Capitalism and the “Functional Antagonism” of Welfare Politics

Schimank and Volkmann [2008] conceptualize economization drawing on Luhmann’s theory of social systems and Bourdieu’s concept of the “social field.” For Luhmann [Reference Luhmann1995], a modern society is composed of functionally differentiated subsystems. Given the complexity of modern society, each social subsystem has a certain function, following its own logic and specific “codes.” While subsystems may be “structurally coupled” and thus “interdependent” (for example, the science system requires a legal framework from the legal system, material resources from the economic system, qualified workers from the education system, and so on), each subsystem is also autonomous in the sense that it is oriented towards fulfilling its own task and, in realizing this function, refers only to its own logic.

Adopting a system-theoretical perspective, economization can be described as the process by which the logic of the economic subsystem is extended to other subsystems, replacing their original functions. In a capitalist system, the economy is oriented towards “exchange value” and the principle of profit-maximization (rather than towards “use value” and the satisfaction of social needs), so that the economic subsystem is autonomous vis-à-vis other subsystems and the economic logic is relatively indifferent to other logics [Schimank Reference Schimank2011: 6-7]Footnote 2.

From this perspective, economization entails the extension of the logic of profit-maximization to non-economic spheres. For example, economization occurs for journalists writing newspapers if the logic of profit-making becomes their only orientation: the new function consisting of selling as many newspapers as possible substitutes the original functions of journalism, such as reporting news truthfully and contributing to the democratic quality of the public sphere by clarifying public issues [Schimank and Volkmann Reference Schimank, Volkmann and Maurer2008: 383].

Thus, the autonomy of each subsystem can be corrupted. While for Luhmann this represents an exception, for Bourdieu the fact that in a capitalist society the economic system threatens the autonomy of the other social fields is the rule [Schimank and Volkmann Reference Schimank, Volkmann and Maurer2008: 384]—and this is especially true of neoliberal capitalism [see Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1998, Reference Bourdieu2003]. Indeed, the universality of money, whereby all social subsystems use money for functioning, makes society as a whole dependent on money and thus on the economic subsystem, so that the capitalist economy eventually tends to subordinate all other subsystems, undermining their autonomy [Schimank Reference Schimank2011: 11]. For this reason, a capitalist economy cannot be reduced to one social subsystem among others: it always tends to expand, imposing its logic on all other subsystems. A capitalist economy is always also a capitalist society [Schimank Reference Schimank2011: 9; Streeck Reference Streeck2012: 2].

For Polanyi [2001], society’s dependence on self-regulating markets and the tendency of the latter to expand to all social domains make capitalist societies potentially self-destroying. This threat in turn generates a so-called “countermovement,” whereby society protects itself against the excesses of capitalism, which—in its progressive formFootnote 3—entails essentially two dimensions: the welfare state and democratic control of the economy. Thus, governments intervening in the name of the “public interest” and “representing the collective claims of ‘society’, act as socio-moral agents” through market regulation and social service provision, with a view to correcting the “distortions of ethically free markets” [Shamir Reference Shamir2008: 5]. From this perspective, the political and cultural construction of “the economy” as an autonomous sphere also implied the affirmation of the “social” as the locus of “non-economic” rationality [Ibid.]. As Marshall [1950: 29] argues, capitalism and social citizenship follow “opposing principles”: social citizenship reposes on the principle of equality among citizens, which opposes capitalism as a system of inequality. Thus, social citizenship supplants the logic of “contract” characteristic of capitalism with that of “status,” replacing “free bargain by the declaration of right” [Marshall Reference Marshall1950: 68]. The rationale of social rights and “decommodification” [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1985] hence amounts to a potential subversion of capitalism, allowing individuals to enjoy a socially acceptable standard of living independently of market participation and allocating welfare according to citizens’ rights, thereby (partially) replacing the market logic in determining the distribution of socioeconomic outcomes.

Importantly, while constituting an antagonistic pole in relation to the capitalist economy, social policy interventions protected not only society from the economy but also crisis-prone capitalism from its own instabilities, so that, taken together, social politics and capitalism formed a “functional antagonism” [Schimank Reference Schimank2011: 11-12]. Social policy is thus both a necessary and inherent component of a capitalist society, and an “intruded” element. Indeed, while referring to a rationale that is at odds with the capitalist logic, social policy is also what allows the existence of an economy oriented towards accumulation, profit and productivity, and indifferent to social needs; that is, precisely because the latter are covered by social policy, the economy can avoid taking them into account [Lessenich Reference Lessenich2008: 25]. Hence, as Offe [1984] argues, the relationship between the welfare state and capitalism is contradictory: the principles of welfare clash with those of capitalism but the non-commodified institutions of the welfare state are necessary preconditions for an economic system based on exchange, which uses labor and other social objects as if they were commodities. Moreover, post-war capitalism greatly depended on social policy provisions: in a Keynesian macroeconomic framework and within a regime of accumulation based on the cycle of mass production and mass consumption (Fordism), welfare states stabilized aggregate demand during economic downturns, acting as a countercyclical factor. Thus, the “functional antagonism” between social politics and capitalist economy involved a “win-win” and self-reinforcing relationship: while economic growth provided resources for pursuing social policy, the latter sustained consumption, thereby benefiting the economy [Donzelot Reference Donzelot1988].

Crucially, the fact that social policy was functional to industrial capitalism does not imply that it emerged spontaneously and/or deterministically. Socio-political interventions aimed at correcting the negative social consequences of a capitalist economy appeared as a result of a “democratic class struggle” [Korpi Reference Korpi1983], using “politics against markets” [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1985]. Also, the regulation of the economy is not “an automatic response to the devastating effects of self-regulating markets” and it is not the result of market forces themselves [Beckert Reference Beckert2007: 17]. Rather, the Polanyian countermovement aimed at establishing the “social” as an opposing pole to capitalism and at subordinating the economy to political-democratic institutions involves deliberate political interventions and is the “unstable result of social and political struggle” [Ibid.: 17]. In other words, within a capitalist society, the degree of autonomy of each subsystem or “field” is the outcome of struggle: “although relative autonomy is a possibility within capitalism, every gain in it has been conquered politically” because autonomy “is conquered not given” [Vázquez-Arroyo Reference Vázquez-Arroyo2008: 139].

In particular, the post-war compromise between capital and labor—between those sections of the economic and political elites who were convinced that such social corrections were needed in order to support capitalism in the long term and the reformist wing of the labor movement [Schimank Reference Schimank2011: 13]—was made possible by a number of political factors. This included the presence of a real alternative to capitalism at the global level [Vázquez-Arroyo Reference Vázquez-Arroyo2008: 154]: the concrete “communist threat” required capitalists to concede compensatory measures and socially oriented reforms to strong unions and social democratic parties in order to prevent the development of revolutionary attitudes among the populace, and the working class in particular. Also, the international order was characterized by the principles of “embedded liberalism” [Ruggie Reference Ruggie John1982], whereby the commitment to international stability and trade was made compatible with national states’ relative autonomy in pursuing social and economic policies, especially through capital control.

Neoliberalism, Economization, and Welfare Retrenchment

The “functional antagonism” between capitalist markets and social policy was undermined by the emergence of neoliberalism, which, according to Schimank and Volkmann [2008: 385], is characterized by a reinforcement of the economization processes inherent in capitalism. This intensification is driven mainly by slower economic growth in relation to the Fordist-Keynesian era. Because in a capitalist society all subsystems depend on resources generated within the economy (either directly or indirectly through tax-based state expenditures), the functional needs of the economic subsystem tend to dominate the whole society. While during the Fordist period, rapidly increasing prosperity (high rates of economic growth) lowered economization pressures, under neoliberalism the dependency of other social subsystems on the economy becomes stronger because fewer and fewer resources are available (given slower economic growth) and competition for those scarce resources increases. In turn, concerns about resource scarcity and competition to obtain them make economic criteria and the economic viewpoint dominant in each social subsystem.

From this perspective, it is possible to link welfare retrenchment with processes of “economization of the social,” entailing the extension of the economic rationale to non-economic areas. Indeed, the lack of economic resources for welfare policies—i.e. fiscal austerity—generates economization because cost-containment pressures make the economic rationale prevail over other possible logics in all spheres of social life. Crucially, economization pressures and welfare retrenchment break the “win-win” relationship between economic and social goals that was at the core of the social democratic compromise. Thus, while the “social” and the “economic” continue to repose on two different logics, they no longer compose a functional, but rather a dysfunctional antagonism. This situation generates competition between social and economic goals: pursuing social goals (e.g. increasing welfare generosity) is in conflict with economic imperatives (e.g. minimizing costs), and neoliberalism involves prioritizing economic goals over social ones. As Peck and Tickell [2002: 394] argue, neoliberalism promotes a “growth first” approach, which reconstitutes “social-welfarist arrangements as anticompetitive costs” and issues of redistribution as “antagonistic to the overriding objectives of economic development” (emphasis in the original). The project of retrenching welfare thus reposes on a “deeply negative theory of the state” and on a trade-off between equity and efficiency [Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck, Morel, Palier and Palme2012: 41-43], whereby efficiency is prioritized over social solidarity [Gill Reference Gill1998a: 18].

To the extent that the austerity framework addresses social issues, it does so on the basis of the “trickle-down” assumption: focusing on economic objectives will, in the long run, benefit all members of society, including the poor and marginalized, thereby also realizing “social” goals. Policy should focus on economic goals—social ones will follow automatically from greater prosperity.

Towards a New Welfare State

If the idea that social policy is a necessary element of a capitalist society is right, then the project of welfare retrenchment cannot be fully accomplished without putting the very existence of capitalism at risk. While the 1980s were dominated—at least at discursive level—by the austerity agenda focused on welfare retrenchment, starting in the mid-1990s, new ideas concerning the relationship between the “social” and the “economic” emerged. These can be linked to the concept of “social investment” as a welfare model that involves “a new understanding of social policy” as a “productive factor, essential to economic development and to employment growth” [Morel, Palier and Palme Reference Morel, Palier, Palme, Morel, Palier and Palme2012: 2]. Hence, rather than a trade-off between social and economic goals, social investment “sees improved social equity as going hand in hand with more economic efficiency” [Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2013: 134]. This perspective has been actively promoted by the European Union, the World Bank, and the OECD [see e.g. Taylor-Gooby Reference Taylor-Gooby2008; Jenson Reference Jenson2010, Reference Jenson and Hemerijck2017; Mahon Reference Mahon2010; Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2018], as well as by prominent academics [e.g. Giddens Reference Giddens1998; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen2002; Morel, Palier and Palme Reference Morel, Palier, Palme, Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2013].

The twofold goal of the “new welfare state” is to protect against the “new social risks,” such as precarious employment, long-term unemployment, and single parenthood [Bonoli Reference Bonoli2005; Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen2002; Taylor-Gooby Reference Peter2004] and to recalibrate social expenditure “from passive to active social policies,” adapting individuals to the “needs” of the “knowledge economy” by means of human capital enhancement [Morel, Palier and Palme Reference Morel, Palier, Palme, Morel, Palier and Palme2012: 9]. Hence, central to this new thinking about welfare is the emphasis on “preparing” rather than “repairing” [Ibid.: 1]: investing in (especially children’s) human capital should prepare people for the needs of the economy, thereby preventing social problems, such as poverty and unemployment, from emerging.

While some scholars see social investment as an alternative to neoliberalism [e.g. Abrahamson Reference Abrahamson2010; Deeming and Smyth Reference Deeming and Smyth2015; Ferrera Reference Ferrera, Mark and Schmidt2013; Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2013, Reference Hemerijck2018; Jenson Reference Jenson2010; Lammers, van Gerven-Haanpää and Treib Reference Lammers, Van Gerven-Haanpää and Treib2018; Mahon Reference Mahon2010; Morel, Palier and Palme Reference Morel, Palier, Palme, Morel, Palier and Palme2012; Perkins, Nelms and Smyth Reference Perkins, Nelms and Smyth2005], others have argued that even if these changes in welfare discourse and policy are important, they do not amount to a paradigm shift and should be considered part of a new phase of neoliberalism. Thus, according to Peck and Tickell [2002: 384], “roll-back neoliberalism” characteristic of the “Thatcher/Reagan era of assault and retrenchment,” “deregulation and dismantlement,” “active destruction and discreditation of Keynesian-welfarist and social-collectivist institutions” has been replaced by “roll-out neoliberalism,” which is associated with an agenda of “active state-building” and “purposeful construction and consolidation of neoliberalized state forms, modes of governance, and regulatory relations” (emphasis in the original). Hence, the neoliberal project “gradually metamorphosed into more socially interventionist and ameliorative forms, epitomized by the Third-Way contortions of the Clinton and Blair administrations” [Peck and Tickell Reference Peck and Tickell2002: 388-389]. This “second-wave neoliberalism” involved an agenda focused on promoting a “socially conscious market globalism” aimed at integrating “market-oriented thinking” with an ethical discourse of social justice [Steger and Roy Reference Steger Manfred and Roy2010: 50-75].

In particular, Jessop [2007] claims that the Third Way involved the “normalization of neoliberalism” [see also Hay Reference Hay2004]. On one hand, the Third Way “warmly embraced the logic of neo-liberal globalization” proclaiming its “inevitability” and “desirability” [Jessop Reference Jessop2007: 284]. On the other hand, it also aimed to “temper the social costs” of neoliberalism [Ibid.: 286], providing “flanking mechanisms to compensate for its negative economic, political, and social consequences” [Ibid.: 288].

Thus, it is possible to observe a recent shift towards more “social,” “inclusive” and “feminist” versions of neoliberalism that emphasize the positive role of the state and of “good governance,” as well as the importance of “social capital,” “gender equality,” and “poverty reduction” [e.g. Craig and Porter Reference Craig and Porter2005; Fine Reference Fine1999; Jayasuriya Reference Jayasuriya2006; Prügl Reference Prügl2017; Ruckert Reference Ruckert2006]. The academic literature has identified at least two different logics at work in these developments. The first relates to the need to compensate losers: “social neoliberalism” reflects “the political realization that some social policy is required to win elections or avoid social unrest” [Dorlach Reference Dorlach2015: 521]. In this context, the goal is to stabilize neoliberalism as a hegemonic project: these “social” measures do not challenge the dominant economic model but provide compensation with a view to advancing the legitimacy of neoliberalism. Following the second logic, alleviating the negative social externalities of neoliberalism is not a matter of political calculations concerned with reinforcing popular consensus; rather, the goal is that of remedying the dysfunctions generated by welfare retrenchment. In particular, drawing on Jessop [Reference Jessop2000], Graefe [Reference Graefe2006: 72] argues that “flanking” measures aim to address the “contradiction between the growing importance of extra-economic factors of production” (such as trust) “and the tendency of neoliberalism to consume such factors faster than they can be reproduced.” In this second “functional” logic, social goals are thus promoted not as essential elements for building hegemonic power but as factors that can help to restore the functionality between social and economic goals, which was lost in the austerity agenda.

Despite their differences, both the “political” logic focused on reinforcing hegemony and the “functional” rationale concerned with remedying neoliberal dysfunctions seem to re-propose the old welfare strategy, whereby a logic clearly distinct from the economic one is called on to counterbalance the economic rationale of capitalist markets, which, if left alone, would destroy both capitalism and society. In short, these changes could be interpreted as efforts to re-establish a “functional antagonism” between social and economic logics. As Graefe [2006: 72] argues, measures attempting “to mitigate the anti-social consequences of neoliberal policies” entail “creating or protecting institutions embodying non-neoliberal principles” (emphasis added).

In the following sections of this paper, I argue that there is a third logic that informs the promotion of social goals in the discourse on the new welfare state, namely the economization logic. Thus, social goals are promoted not only with a view to enhancing the legitimacy of neoliberalism and to remedying its dysfunctions but also because the “social” itself is re-interpreted in economic terms. The “new welfare state” then reconciles social and economic goals through the economization of the social, which is in line with—not in opposition to—the neoliberal rationale. Indeed, re-framing social goals as economic investments makes it possible to implement measures for ameliorating social outcomes without the need to refer to “non-neoliberal principles.”

Two Roads to Economization and The Rise of “Social Impact Bonds”

In the new welfare discourse, there are two essential ways in which the “social” becomes economically productive and an investment object. The first involves the shift from “decommodification” to labor market empowerment as a central welfare principle. While the post-war welfare state aimed to protect individuals from the (labor) market, the new welfare state aims to include them in the market through human capital enhancement. Indeed, social investment “is essentially an encompassing human capital strategy” [Hemerijck Reference Hemerijck2013: 142; Leibetseder Reference Leibetseder, Schram and Pavlovskaya2018], which seeks to “rebuild the welfare state around work” [Deeming and Smyth Reference Deeming and Smyth2015: 299]. Social investment is thus part of the “politics of inclusion” that transforms social citizenship into a “market citizenship,” which seeks to enable participation within the economic order [Jayasuriya Reference Jayasuriya2006; see also Nullmeier Reference Nullmeier2004; Plehwe Reference Plehwe, Mackert and Turner2017]. In this context, while social entitlements may be generous and expansive, they are justified “in terms of their capacity to enable the greater participation of individuals within the economic mainstream” [Jayasuriya Reference Jayasuriya2006: 31].

The second way in which the “social” becomes an investment object involves the principle by which “preventing” the emergence of social problems is less expensive than “repairing” them. On this second road to economization, social problems such as crime, low education, illness, and unemployment are framed in terms of their economic costs for the public budget: “Poor people and those with various social needs are seen as expensive for the state to the extent that they use government resources and programs” [Kish and Leroy Reference Kish and Leroy2015: 635]. Social interventions are then framed as investments because they solve or prevent problems that are constructed as economic costs [Dowling Reference Dowling2017: 300]. This second approach thus targets highly disadvantaged populations, which are framed not primarily as human capital or labor power (as in the first way of investing in the social) but as “subjects who can be recuperated into worth to the extent that social rehabilitation attempts to discipline them into costing the state less over time” [Kish and Leroy Reference Kish and Leroy2015: 636].

Reinterpreting social policies as economic investments that deliver returns, either in terms of enhanced productivity and higher employment rates, or in terms of savings for the public budget—or both—implies that, in order to finance this kind of interventions, it is possible to attract for-profit private capital. Indeed, given that these interventions generate benefits for the public budget, the state is able to pay a return to private actors that invest in these social programs. This is the basis for the development of “social impact bonds,” which are innovative financial instruments that allow financial actors to invest in social policy interventions and earn a profit on them if they are successful in achieving their pre-established outcomes. In this context, poverty and social disadvantage become “investable” objects [Baker, Evans and Hennigan Reference Baker, Evans and Hennigan2019] and the social is made “profitable” [Dowling and Harvie Reference Dowling and Harvie2014: 880], transforming social problems into investment opportunities for financial elites [Bryan and Rafferty Reference Bryan and Rafferty2014; Cooper, Graham and Himick Reference Cooper, Graham and Himick2016; Dowling Reference Dowling2017; Joy and Shields Reference Joy and Shields2018; Kish and Leroy Reference Kish and Leroy2015; McHugh et al. Reference Mchugh, Sinclair, Roy, Huckfield and Donaldson2013; Ryan and Young Reference Ryan and Young2018]. This “de-differentiation” of welfare states and financial markets [Rohringer and Münnich Reference Rohringer and Münnich2019] implies the “financialization” of social policy—which is in line with the argument that among the many forms that economization can take, in the contemporary context the “financialised form appears to be particularly predominant” [Chiapello Reference Chiapello2015: 15].

Social impact bonds are still in an experimental phase and are not yet widely used. However, they are diffusing very rapidly [Burmester, Wohlfahrt and Kühnlein Reference Burmester, Wohlfahrt and Kühnlein2018: 82; Edmiston and Nicholls Reference Edmiston and Nicholls2018: 58] and are increasingly supported by crucial international players, such as the World Bank, the OECD, JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Deloitte, KPMG, and McKinsey & Co [Joy and Shields Reference Joy and Shields2018].

What matters most in the context of this paper is that social impact bonds make visible the performativity of social investment discourse: applying economic reasoning to social policy has the potential to actually transform the latter into an economic object, thereby promoting also profit-making opportunities within non-economic domains.

Thus, in the case of social investment, the two types of economization described by Griffen and Panofsky [2021] work quite linearly: the diffusion of the economic frame to welfare discourse (first type of economization) has been translated into the creation of new policy devices—social impact bonds—that concretely transformed social policies into economic objects that can be manipulated in economic terms (the second type of economization). Yet, while these two modes of economization in this case go hand in hand, it is important to highlight that they nevertheless reflect different “interests and aims of competing social actors,” as argued by Griffen and Panofsky [Ibid.: 519]. Indeed, the discourse of social investment was initially promoted by progressive scholars, such as Giddens [1998] and Esping-Andersen and colleagues [2002], who used the economic argument for advancing social policies in a neoliberal, “economized” context. Thus, the economization of the first type was instrumental in promoting welfare generosity, as the economic argument was used to convince the political and economic elites to “invest” in social policy. However, more recently the application of economic reasoning to social policy has been radicalized—through the economization of second type—by financial actors who have reversed this relationship between ends and means: rather than the economic logic being at the service of social policy promotion, it is now the latter that becomes a profit-making opportunity. In this context, while economization is not disconnected from moral discussions and values, it seems that morality is used mainly as a source of legitimization for the economic and political power of the financial elites. As Dowling [2017: 296] argues, social impact bonds are part of an attempt to rehabilitate the public image of the financial sector after the global financial crisis: they make it possible to extend the reach of finance in a morally defensible way so that rather than “curbing the power of finance, the solution lies precisely in promoting it.”

From “Functional Antagonism” to Functional Incorporation

While for Hemerijck [2012: 49] social investment—unlike the “Keynesian welfare state and the neoliberal retrenchment movement”—is “not founded on one unified body of economic thought,” I argue that the emergence of social investment is based on two pillars of economic theory. The first is “post-Walrasian” and institutional economics, which acknowledges market failures (e.g. problems such as asymmetric information, externalities and actors’ bounded rationality) and calls for corrective state intervention as long as it is economically efficient [Lapavitsas Reference Lapavitsas, Saad-Filho and Johnston2005; Madra and Adaman Reference Madra Yahya and Adaman2014]. The state-market dichotomy that informed welfare retrenchment is thus replaced by a discourse that emphasizes the complementarity between state and market. The second pillar involves the naturalization of economic thinking and universal application of market principles, whereby, rather than a science concerned with studying a specific object (i.e. the “economic domain” or “economic action”), economics is used as an approach and a way of seeing the world [Zuidhof Reference Zuidhof2014: 176-177]. This pillar builds on the work of Gary Becker on “human capital,” whereby economic assumptions concerning human behavior are extended to non-economic domains, such as education, crime, family life, health, and so on. In this context, “economic orthodoxy is no longer positioned in opposition to the social but, instead, presents itself as the preferred intellectual apparatus to frame our thinking about the social” [Brodie Reference Brodie2007: 102]. Thus, “the epistemological distinction between economy and society” collapses: the “rationality of the market” is no longer conceived “as a distinct and limited form of social action,” but is posited “as the organizational principle for state and society as a whole” [Shamir Reference Shamir2008: 6]. Therefore, the epistemological distinction between economy and society is dissolved not in the way an economic sociologist or an anthropologist would do it—pointing to the fact that the economy is part of society and economic action is a particular case of social action—but interpreting all social relations as economic and as grounded in the rationality of markets: moral and social issues are framed through the “foundational epistemology” that dissolves the distinction between market and society, encoding the “social” as a “specific instance” of the “economy” [Ibid.: 14]. This corresponds to the “epistemic” core of neoliberalism. Through economization, neoliberals “attempt to re-define the social sphere as a form of the economic domain,” thereby “eliding any difference between the economy and the social” [Lemke Reference Lemke2001: 197]: extra-economic domains are “colonized by criteria of economic efficiency” and thus rendered economic [Ibid.: 202].

In particular, in the discourse of the new welfare state, the “social” is reframed from within the economic: the economic logic is extended to its antagonistic pole, eliminating the antagonism. Social goals are promoted not as compensation for economization processes but thanks to and through such processes: social goals are promoted to the extent they are made economically attractive and because of that. While welfare retrenchment followed a “trickle-down” approach, assuming that social goals would emerge as by-products of economic growth, social investment reverses the relationship between social objectives and economic growth, making the promotion of the social itself an engine for economic growth. Solving social problems thus becomes an economic goal and investing in social policy a driver of “competitiveness.”

From this perspective, in the discourse of the new welfare state, there is no functional antagonism between the social and the economic logics—as there was within the social democratic framework—nor a dysfunctional antagonism (as in the case of welfare retrenchment, where economic and social goals are in tension and the economic dominates over the social). In the context of social or inclusive neoliberalism, instead, the functionality between social and economic goals is restored but the economic has actually incorporated the social so that functionality is achieved rejecting the antagonism altogether, i.e. rejecting the plurality of logics. Hence, while also the Keynesian welfare state involved the reconciliation of social and economic goals, the new welfare discourse removes the “dialectic understanding” between the social and the economic [Hansen and Triantafillou Reference Hansen Magnus and Triantafillou2011]. There is only one logic—the economic one—which alone is sufficient for promoting social goals. The “social” rationale of de-commodification and social rights—the oppositional pole with regard to capitalist markets—appears superfluous and social policy is no longer based on a different logic with respect to capitalism but adopts its very logic.

Thus while for Craig and Porter [2005: 257] “social capital” and “social investment” constitute “ideological oxymorons”—which makes perfect sense, assuming a fundamental and unavoidable tension between the economic and the social—social neoliberalism attempts precisely to abolish any contradiction, reframing “socio-moral concerns from within the instrumental rationality of capitalist markets” [Shamir Reference Shamir2008: 3, emphasis in the original]. While social citizenship followed a radically different logic from the capitalist rationale, in the discourse on the New Welfare State the social is based on the same economic logic as capitalist markets.

However, economization not only involves an “episteme” [Madra and Adaman Reference Madra Yahya and Adaman2014: 692], in other words, an interpretative grid for policymaking that adopts economic principles for governing the social. Reframing the social in economic terms also extends opportunities for profit-making for the economic and financial elites, most notably through social impact bonds. Thus, the antagonism in social investment is avoided not only at the level of logic, eliminating the conflict between the social and economic rationales through the economization of the social. Also the social conflict is potentially suppressed: while welfare states emerged in the context of political and social struggles, and the functional antagonism of the social democratic compromise was based on the bottom-up dynamics of the democratic struggle, functional integration follows a “top-down” and “elite-driven” approach, which does not require political action or the mobilization of collective actors [Craig and Porter Reference Craig and Porter2005: 257; Dorlach Reference Dorlach2015: 538]. The New Welfare State is potentially based on a de-politicized consensus in which the economic elites have an opportunity to invest in solving the social dysfunctions that capitalism itself creates. In other words, there is no longer a need for a political subject opposing the capitalist elite fighting for political solutions to capitalist dysfunctions, as the working class did in the course of the emergence of welfare states. Through social investments, the capitalist class itself can invest in remedying the negative social externalities of capitalism, obtaining a profit on this investment.

The Economization Paradox

Schimank and Volkmann [2008: 385-386] identify five degrees of economization. In the first degree, actors in a given social subsystem do not need to consider the economic impact of their decisions (in other words, economic aspects are irrelevant). In this case, the subsystem is fully autonomous and focuses exclusively on performing its own function. For example, in the health subsystem a person may be cured independently of the costs involved and of their ability to pay: the only relevant information in the process of choice is the fact that the person is ill and needs health care; no economic reasoning comes into play because the resources needed are readily available or can be easily found.

In the second and third degrees, economic aspects influence the process of choice through the consciousness of costs, which become external constraints on performance of the subsystem’s function. While in the second degree economic aspects imply the norm “you should avoid incurring economic losses,” in the third degree they involve the norm “you must avoid incurring economic losses.” Thus, in the second degree, the subsystem still focuses on its main function and is supposed to consider only the costs, trying—whenever possible—to minimize them. For example, if confronted with a choice between two equally efficacious medicines, actors in the health system are encouraged to adopt the cheapest one. By contrast, in the third degree, the minimization of costs becomes an unavoidable restriction on pursuit of the function of the subsystem. This happens, for example, when a necessary medicine is not made available because it is too expensive. At this level economization already corrupts the functioning of the subsystem.

With the fourth and fifth degrees, economization substantially increases because the logic of cost containment is replaced by the logic of profit maximization. In the fourth degree, profit enters the process of choice in a non-economic subsystem as a “should-expectation,” following the norm “you should make profit,” which becomes the second objective after the original function of the subsystem. Finally, in the last degree, making a profit becomes a “must-expectation” and the only objective of the social subsystem. Thus, profit maximization replaces the original function of the subsystem, which thus no longer pays attention to its “code.” Here full economization occurs and the subsystem loses its autonomy.

Post-structuralists and constructivists who reject the existence of social subsystems might possibly simplify this framework, highlighting that among the many possible principles and forms of rationality for valuing social objects—none of which are inherent in the objects themselves—economization represents a specific “mode of valuation.” Nevertheless, the distinction between cost containment and profit maximization remains useful. Thus, even adopting a post-structuralist perspective, it may be relevant to distinguish between different degrees of economization. Economization is then the process by which social objects are increasingly valued and treated in economic terms. At low levels of economization, social goals can be valued with reference to various logics while trying to minimize the costs that emerge from the realization of such goals. In contrast, full economization entails replacing all other possible modes of valuing social goals with the rationale of profit maximization.

Independently of the perspective adopted, what matters is that economization increasingly undermines the possibility of following other logics than the utilitarian one and of realizing other goals than profit maximization. Linking this five-degree economization framework with social policy, we can observe that welfare retrenchment and fiscal austerity generate economization pressures in the form of cost containment. Fiscal austerity implies that fewer and fewer resources are available for welfare benefits, schools, hospitals and other social services. The logics and goals pursued in schools, hospitals and welfare policies may remain distinct from economic ones, but austerity makes it more difficult for these subsystems to function according to non-economic logics and to realize non-economic goals.

The paradox of social investment is that higher degrees of economization are linked to an improvement of social goals with regard to welfare retrenchment: this variant of neoliberalism is more “social” than welfare retrenchment precisely because it downplays social logic, rendering the social an economic object. For example, when improving people’s health and education is interpreted as an investment rather than a cost to be minimized, then hospitals and schools can potentially obtain more resources. At the same time, the logic and goals pursued in these social institutions tend to become primarily economic. For example, education is conceived as an economic investment in children’s human capital, which leads to a focus in school curricula on enhancing work-related skills rather than on educating for personal well-being and democratic citizenship [e.g. Lister Reference Lister2003]. The new welfare agenda is then more generous than austerity while, at the same time, involving a deeper intrusion of market logics into social life.

Economization and De-Democratization

Economization processes are thus not necessarily associated with negative social outcomes—and, indeed, deeper economization may lead to improvements in social policy generosity. The problem with the economization of the social is rather that it also entails its de-politicization [Madra and Adaman Reference Madra Yahya and Adaman2014].

Economization promotes de-politicization and de-democratization because it replaces political judgments with economic calculation as the dominant framework for decision-making [Brown Reference Brown2003, Reference Brown2006; Clarke Reference Clarke2004: 34-35; Davies Reference Davies2014; Kiely Reference Kiely2017].Footnote 4 Economization then represents a way to escape conflicts of values: there is no need to refer to contested notions of social justice for formulating policy proposals; it is enough to consider cost-benefit analysis, which is presented as “pragmatic” and “rational”—as opposed to democratic politics, which are portrayed as “ideological” and “dogmatic” [Clarke Reference Clarke2004: 37].

But even if presented as rational and pragmatic, the economization of the social is not neutral. In particular, economization entails an ideology of efficiency and economic growth. Thus, if democratic politics is also about establishing the limits of the efficiency logic and which areas of social life should be governed by other logics [Streeck Reference Streeck2012: 8], then economization—extending economic logic to the whole society—systematically undermines the possibility of engaging in politics. The latter is reduced to efficient administration, whereby there is no scope for a debate on the good society and, say, the “limits of the market” [Sandel Reference Sandel Michael2012]. Economization then sustains the “commodified mentality” of “market civilisation” [Gill Reference Gill1998a: 13] where economic criteria are the highest arbiters of social value and of what is valuable. The only way to promote social goals within neoliberalism is to transform them into economic goals, because only what is economically valued is considered valuable.

Economization thus justifies some forms of state intervention while precluding others. For example, social investment aims to maximize employment and employability, thereby implicitly devaluing non-market activities and all life spheres that are not employment-related and cannot be included in a human capital–enriching approach [Saraceno Reference Saraceno2015]. Similarly the critical literature on social impact bonds has highlighted that the latter tend to: encourage a focus in public action on interventions that produce quantifiable results, thereby encouraging the simplification of complex problems for the sake of establishing performance indicators; legitimize interventions that are cost-reducing and focused on promoting labor market inclusion; endorse a pro-market ideology and an entrepreneurial culture, also encouraging non-profit organizations delivering social services to adopt business-like attitudes; marginalize the voice and agency of both service users and frontline social workers; and encourage a focus on the symptoms of social problems rather than their root causes, for example, by promoting individualized and de-politicized interventions centered on individuals’ behavioral and psychological-motivational changes [Bryan and Rafferty Reference Bryan and Rafferty2014; Chiapello and Knoll Reference Chiapello and Knoll2020; Cooper, Graham and Himick Reference Cooper, Graham and Himick2016; Dowling Reference Dowling2017; Joy and Shields Reference Joy and Shields2018; McHugh et al. Reference Mchugh, Sinclair, Roy, Huckfield and Donaldson2013; Ryan and Young Reference Ryan and Young2018; Sinclair, McHugh and Roy Reference Sinclair, Mchugh and Roy2019].

From this perspective, social investment is not about transformative solutions—such as the substantive redistribution of political and economic power in society—that would endanger its “win-win” logic. Social impact bonds may even contribute to the consolidation of inequalities. Because “the conditions that make finance so profitable in the first place […] are the very same conditions that cause and exacerbate the forms of dislocation finance now proposes to fix […] financiers benefit twice from the conditions of neoliberalism […] [and] they profit by ‘solving’ the very social problems they have helped create and/or have benefited from” [Kish and Leroy Reference Kish and Leroy2015: 646].

Economization thus de-politicizes the social also in the sense that it disconnects social problems from issues of oppression, domination and structural injustice. In this context, economic calculation in fact serves to cover the fact that powerful interests remain unchallenged while seeking solutions to collective problems and social dysfunctions.

Against this background, economization involves a shift from the deontological ethics and political logic that inform the institution of social rights to the consequentialist-utilitarian ethics and de-politicized-technocratic economic calculation that inform neoliberalism. In this shift, social rights are transformed from self-imposed legal obligations and limitations on public action established through political-democratic means into economic objects, subordinated to market rules and thus to economic power. Hence, social investment does not challenge the economic “constitutionalism” that characterizes neoliberalism [Jayasuriya Reference Jayasuriya2006]: political decisions remain more responsive to the discipline of economic criteria and “correspondingly less responsive to popular-democratic forces and processes” [Gill Reference Gill1998a: 5], and the “investor” remains the “sovereign political subject” [Gill Reference Gill1998b: 23]. Similarly, the neoliberal transformation of the state from an institution financed through taxation into a “debt-collecting agency on behalf of a global oligarchy of investors” [Streeck Reference Streeck2011: 28] is not reversed. Rather, social investment inscribes social rights in the neoliberal, “post-democratic” [Crouch Reference Crouch2004] constitution, reframing them as investment objects. This makes it possible to promote social goals without challenging the epistemic dimension of neoliberalism centered on economization and without undermining the interests of the economic and financial elites who can invest in—and earn a profit on—the solution to social problems. In this context, social goals are promoted as long as they are compatible with economic ones—in both their epistemic and distributive aspects—whereas, in cases of conflict, the latter should prevail.

Conclusion

In this paper I have connected debates on neoliberalism within (neo-Marxist) political economy with the Foucauldian literature on neoliberal governmentality, with the goal of theorizing the nature of neoliberal social policy. Within political economy, capitalism is studied not as an economic system that exists outside of society, but as a social order “that is precisely about the relationship between the social and the economic” [Streeck Reference Streeck2012: 3]—a relationship, which is never stable and evolves over time. During the neoliberal era, capitalism “became progressively more capitalist” eroding those socio-political institutions that characterized the post-war social-democratic compromise [Streeck Reference Streeck2010: 164]. Thus, neoliberalism is associated with an intensification of economization processes already inherent in capitalism, whereby the “economic” comes to dominate the “social.” From a very different perspective, Foucault [2008: 240-242] comes to a similar conclusion: applying an “economic grid” to a field previously defined “in opposition to the economy,” or at least “as complementary to the economy,” and in which “the economy itself is situated”—namely, society—neoliberalism inverts the relationship “of the social to the economic,” promoting the “economization of the entire social field.” Hence, economization processes link these two otherwise conflicting perspectives on neoliberalism: extending the economic logic to non-economic areas (neoliberalism as a governmental rationality) also makes it possible to increase the possibilities for capitalist accumulation in previously uncommodified domains (neoliberalism as a class project).

On this basis, I have argued that the central feature of neoliberal social policy lies in the economization of the social. This conceptualization allows us to connect not only different definitions of neoliberalism but also opposing welfare reform agendas, such as welfare retrenchment and social investment. While welfare retrenchment imposes economization pressures in the form of cost containment, social investment promotes economization by inserting the logic of profit and productivity in the social sphere. Thus, the central paradox of social investment is that it is more socially-oriented than fiscal austerity because it involves higher degrees of economization. Indeed, rather than leaving the social rationale intact while imposing cost reductions—as austerity does—social investment attempts to eliminate the antagonism between social and economic goals by transforming the social into an economic entity and an investment object. However, this is precisely what makes it possible to value and promote social goals in a neoliberal context, that is, without challenging neoliberalism in its epistemic and distributive dimensions. Thus, from a social justice perspective, it is better to have social investment than austerity: it is better to have investment in schools than budgetary cuts, even if they are undertaken for the sake of a rather narrow “human capital enhancement,” and it is better to have more financial resources devoted to inclusion programs for unemployed and homeless people than to reduce social expenditures in these fields, even if the goal is to reduce costs for the public budget.

Of course, this advantage is also the main problem that those interested in progressive social change see in social investment. The latter consolidates the main features of neoliberal society, where only what has an economic value is valuable, and leaves unchallenged—and possibly even reinforces—the inequalities and power asymmetries that characterize neoliberalism. Hence, if we consider the economization of the social to be a central aspect of neoliberalism, then social investment is “more neoliberal” than austerity: social investment radicalizes the neoliberal project in both its epistemic dimension, linked to extension of the economic rationale to non-economic spheres, and in its distributive dimension, whereby the social is reframed as an economic object in which the economic elites can invest to make a profit.

Moreover, while welfare retrenchment is ultimately self-defeating because, in the long run, it risks undermining the existence of capitalism itself [Offe Reference Offe1984], social investment provides the best solution—from the capitalists’ viewpoint—to the dilemma of capitalism and the welfare state. On one hand, it provides the welfare institutions upon which capitalism ultimately depends. On the other hand, however, it does so relying on the same capitalist logic rather than on following opposing principles, such as decommodification and social rights. By means of social impact bonds, the provision of welfare is commodified and the social becomes an investment object, thereby eliminating the heterogeneity of values and principles. Extending the economic logic and the principle of exchange to the institutions of the welfare state approximates the neoliberal utopia of a society entirely regulated through markets. There is no need to appeal to solidarity or social justice: self-interest is enough because investing in the social delivers financial profits. And there is no need for authority-based political interventions or coercive redistribution: because investing in the social becomes attractive from the economic viewpoint, freedom of contract is sufficient.

All in all, while it is certainly true that the Keynesian welfare state should not be romanticized as representing the normative ideal of social and political justice [Cahill and Konings Reference Cahill and Konings2017: 110; Fraser Reference Fraser2013], social investment represents an even weaker realization of this ideal. Under Keynesianism the social and economic dimensions were reconciled not only through the positive contribution of the welfare state to the economy but also through the regulation of the economy in the public interest [Cerny Reference Cerny Philip1997: 258], that is, the partial “socialization” of the economy. Moreover, the relationship between the social and economic dimensions was dialectic, so that the reconciliation process depended strongly on democratic politics, including social conflict. Thus, in the era of “embedded liberalism” [Ruggie Reference Ruggie John1982], nation states (at least in the Global North) enjoyed relative autonomy in pursuing economic and social policies and were responsive to domestic social forces—an “insulation” of democratic politics from global markets achieved especially through capital control.

In contrast, neoliberalism is associated with the liberalization of financial markets and a deepening of economic globalization, which, despite cross-country differences, imply that the economy is (perceived as) out of democratic control, whereas international financial markets—rather than domestic electorates—eventually become the central “constituency” that influences political choices [Fourcade and Babb Reference Fourcade and Babb2002]. In this context, the “socialization” of the economy is presented as no longer possible, so that the only way to reconcile social and economic goals is through the economization of the social. The reconciliation of the social and the economic thus becomes a technocratic matter to be managed rather than a political issue to be democratically discussed and involving social struggles.

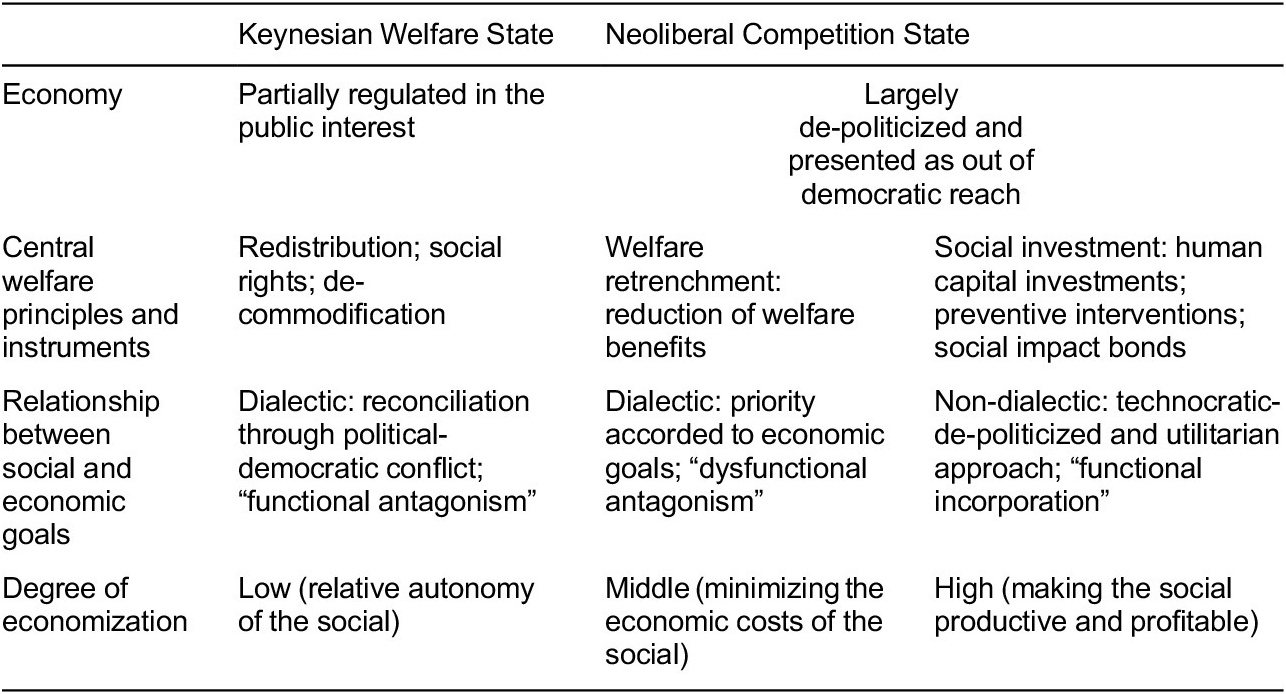

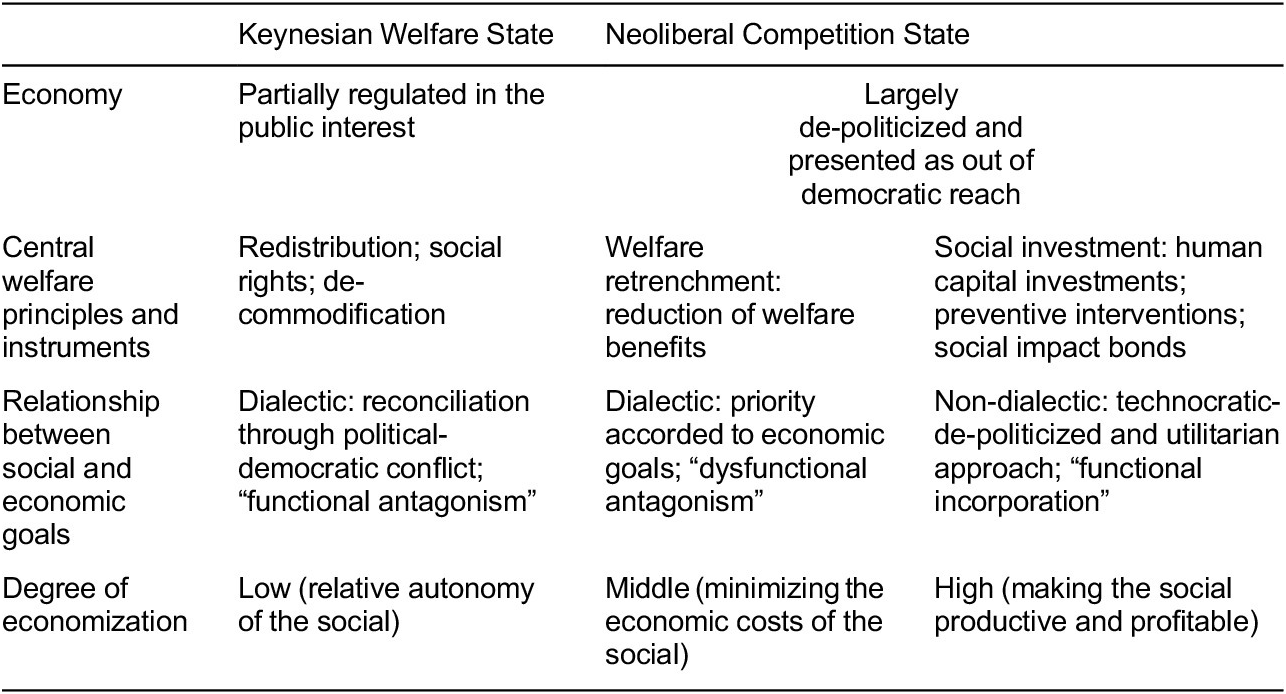

From this perspective, the social investment state remains—like the austerity state—largely a democratically unresponsive “competition state” that needs to attract globally mobile capital. The difference with regard to the welfare retrenchment approach is that within the framework of social investment social policy is not conceived as a cost to be minimized but as a productive factor, contributing positively to economic growth and competitiveness. In this context, while higher degrees of economization may be associated with greater generosity in social policy, the goals and logics of the latter are transformed: social policy generosity is increased but the goals of social policy shift towards economic aims, such as enhancing human capital and inserting individuals in the labor market (Table 1 on the next page summarizes the main arguments of the paper).

Table 1 Summary of the main arguments

Importantly, although I have presented social investment as a perspective that emerged in a historical period subsequent to that of welfare retrenchment, the policy responses to the crisis that started in 2008 for many countries entailed a return to austerity and retrenchment. Hence, welfare retrenchment and social investment may be better interpreted as two different expressions of neoliberal social policy rather than as two historical periods within the “neoliberal era.”

Moreover, at the time of writing social investment is still an emerging framework for welfare reform—and this is especially true for social impact bonds, which are in an experimental phase. Thus, it is not clear whether social investment will become the central normative orientation for welfare reform or retrenchment will prevail. Symmetrically, the emergence of a progressive post-neoliberal social policy cannot be excluded neither. For this, however, and in contrast to a widespread view, it is not enough to increase social policy generosity within the economization framework. What is needed is a democratization process informed by reference to other values and logics beyond utilitarian ones and aimed at subordinating both social policy and the economy to democratically-defined social needs.

This has important implications also for scholars. Indeed, the “social investment” discourse was originally initiated by progressive academics (non-economists) who used the economic argument to convince political and economic elites to “invest” in social policy. Financial actors have now radicalized this economic argument, however: with social impact bonds, welfare interventions are effectively transformed into economic objects in which it is possible to invest to make a profit—with the evident risk of de-democratizing social policy and further reinforcing inequalities. Thus, very much like the concept of “social capital,” social investment too appears to be a “Trojan horse”: while using economic language may help economists and the political elites following their advice to see the economic benefits of the “social,” the transformation of non-market social practices and values into new sources of previously untapped economic value in the end undermines democratic goals and “destroys the very social it aims to valorize” [Somers Reference Somers and Steinmetz2005: 270].

From this viewpoint, it may be better to consider social policy an economic cost for achieving socio-political objectives established through democratic deliberation than as an investment and to let the economic rationale alone determine the kind of social policy of the future. Alternatively, if one wishes to maintain the appealing concept of “investment,” then it should be made clear that the latter has a socio-political rather than an economic meaning; in other words, that societies can decide in which areas they want to “invest” and for what purposes—including non-economic ones. Also in this case, however, it seems important to rehabilitate a dialectical understanding of the relationship between the “social” and the “economic,” which would facilitate democratization through the re-politicization of public issues, instead of promoting the consensual economization of everything.