INTRODUCTION

After World War I, the International Labour Organization (ILO) focused on the serious issue of forced labour in colonies, which often involved violence or conditions similar to slavery.Footnote 1 The Forced Labour Convention of 1930 was the ILO’s response to this exploitative treatment. The convention defined forced or compulsory labour as “[…] all work or service which is extracted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily […]”, which will also be the definition used in this analysis.Footnote 2 As a supporter of the abolition of forced labour for private industries, Britain was the first colonial power to sign, in 1931. The convention had severe consequences for the public sector and especially for road labour in the Gold Coast, which was carried out mainly as forced labour under chiefs. In contrast to forced labour for private industries, the convention did not abolish forced labour for public works. Penal and communal labour in the public sector as well as compulsory military work or service were exempted under certain conditions.Footnote 3 Forced labour for public works was a central aspect of colonial economies, especially for road labour, as export economies depended on roads. The system of road maintenance continued after an exhaustive debate on legal loopholes and exemptions of the convention. The present analysis primarily focuses on road maintenance, meaning the clearing and upkeep of roads, as it was specifically road maintenance that was of immediate concern to colonial officials regarding the adaption of the Forced Labour Convention in the Gold Coast. In what ways and to what extent forced labour continued in other sectors is an issue for further research.

This article will explore how the colonial government applied the convention in the Gold Coast to enable the continuance of the existing system of forced labour for road maintenance under chiefs. I will focus on the ways in which the government reacted to the strict legal and financial regulations governing exemptions from the convention, and look into how the issue of road maintenance and forced labour resulted in the introduction of direct taxation and the expansion of indirect rule in 1930. It is crucial to analyse how the investment of chiefs with administrative functions and powers within the colonial government was explicitly planned in context of the Forced Labour Convention. Additionally, this article examines which forms forced labour took after the implementation of the Forced Labour Convention.

Where evidence of forced labour is not clearly visible, scholars can identify more subtle forms of labour coercion. As Guthrie argues, it is crucial to understand that forced labour consists of a broad spectrum of coercive practices.Footnote 4 Examining different forms of such practices in British colonies, it is useful to take a legal and administrative perspective, as recent studies by Okia and Keese emphasize; especially in the context of ILO conventions.Footnote 5

Shifts in labour policies and regulations can be induced either directly by the state or be enforced upon the state by an external body such as the ILO. Of course, in the colonial context, the metropole can also be considered as an external body that enforces such shifts onto the colonies.Footnote 6 The Gold Coast administration was legally bound to enforce the labour regulations of the ILO, even though an ensuing shift in labour relations was not in their interest. How effective was the convention in changing labour relations on the ground, and attaining the ILO’s goal of controlling forced labour and improving labour conditions in the colonies? The convention gave colonial governments leeway in adopting the convention, and the Gold Coast government certainly used this leeway for their particular economic interest. In this respect, this study concurs that colonial labour policy was not just made in London (or Geneva, for that matter), but intrinsically informed and formed by developments and realities in the colony.Footnote 7

After a brief explanation of indirect rule and an overview of notions of communal labour as well as forced labour in connection to chiefs, the article will discuss the ILO and notions of civil education and forced labour in African colonies. The article then explains the centrality of road maintenance for the implications of the convention. The following section analyses the intrinsic connection between the convention and the regulation on administrative functions of chiefs, and the introduction of indirect rule in the Northern Territories. With regard to the administrative function, direct taxation was of explicit interest in the continuation of road maintenance under chiefs and is therefore scrutinized in detail. Finally, the article details the colonial government’s approach to reporting forced labour to the ILO. Since the article draws mainly on the internal discussion of colonial officers, an analysis of reports to the ILO and the reaction to those reports can contribute to the understanding of the British strategy of obfuscating the fact of forced labour.

The analysis largely uses original sources held by the Public Records and Archives Administration Department (PRAAD) in Accra and Tamale, in particular colonial internal correspondence on the implications of the Forced Labour Convention and policymaking. Though the regional archive in Tamale holds sources that discuss policymaking on road maintenance, records on actual road maintenance for the period under analysis are absent. The colonial government may have purposefully destroyed such records in the process of decolonization. Another limitation this study faces is the analysis of the perspective of workers and chiefs, as archival sources on these actors are either absent, or only given through colonial officials. Illiteracy was prevalent in the North in the 1930s and 1940s, even amongst chiefs, so hardly any written sources exist. Though newspapers are increasingly used in African history to reconstruct, or reflect, on local perspectives, this is not feasible for the Northern Territories in the 1930s and 1940s, as newspapers hardly circulated in the North and seldom reported on the area. Oral history is unfortunately not a viable alternative, as the actors who were contemporary witnesses are no longer alive.

INDIRECT RULE AND FORCED LABOUR IN AFRICA

‘Indirect rule’ describes the incorporation of local authorities into the administration of the colonial government, in which they perform, but also derive certain powers and functions, based on Frederick Lugard’s Dual Mandate.Footnote 8 Lugard developed the system of indirect rule in Northern Nigeria, where he served as the High Commissioner, after the conquest of the Sokoto Caliphate in 1902. As Lugard considered the existing administrative infrastructure and institutions of the caliphate more efficient to rule over the population than a newly introduced colonial system, the emirs continued as rulers under the control of the colonial administration. In this respect, the colonial administration did not rule the population directly, but indirectly through the emirs, who enforced colonial policies.Footnote 9 According to Lugard, direct taxation enabled chiefs to rule financially independent from the colonial government, which was central for the sovereignty of chiefs. At the same time, he argued that direct taxation supported the abolition of forced labour and slavery for public works, as it could finance waged labour.Footnote 10 Yet, in British colonies such as South Africa and Tanganyika (today Tanzania), direct taxation was introduced to enforce colonial authority and to force men to commit to waged labour to be able to pay the tax.Footnote 11 Labour for public works, in contrast to the industrial economy, did not directly generate money or capital for reinvestment. In contrast to Lugard’s ideas, this case study shows that even though direct taxation was introduced, coercion was still exerted and included in colonial labour policy.

In the Northern Territories, indirect rule was enforced in the aftermath of the Forced Labour Convention to invest chiefs with the necessary administrative functions to continue securing forced labour for road labour. The administrative development of chieftaincy is crucial in terms of a shift in labour regulations as well as labour relations that took place in the Gold Coast, as the chiefs exerted colonial labour policies through indirect rule.Footnote 12 However, this article does not claim that this administrative development created a despot that was “liberated” from constraints to his rule that were posed by his peers or his people, as Mamdani argues.Footnote 13

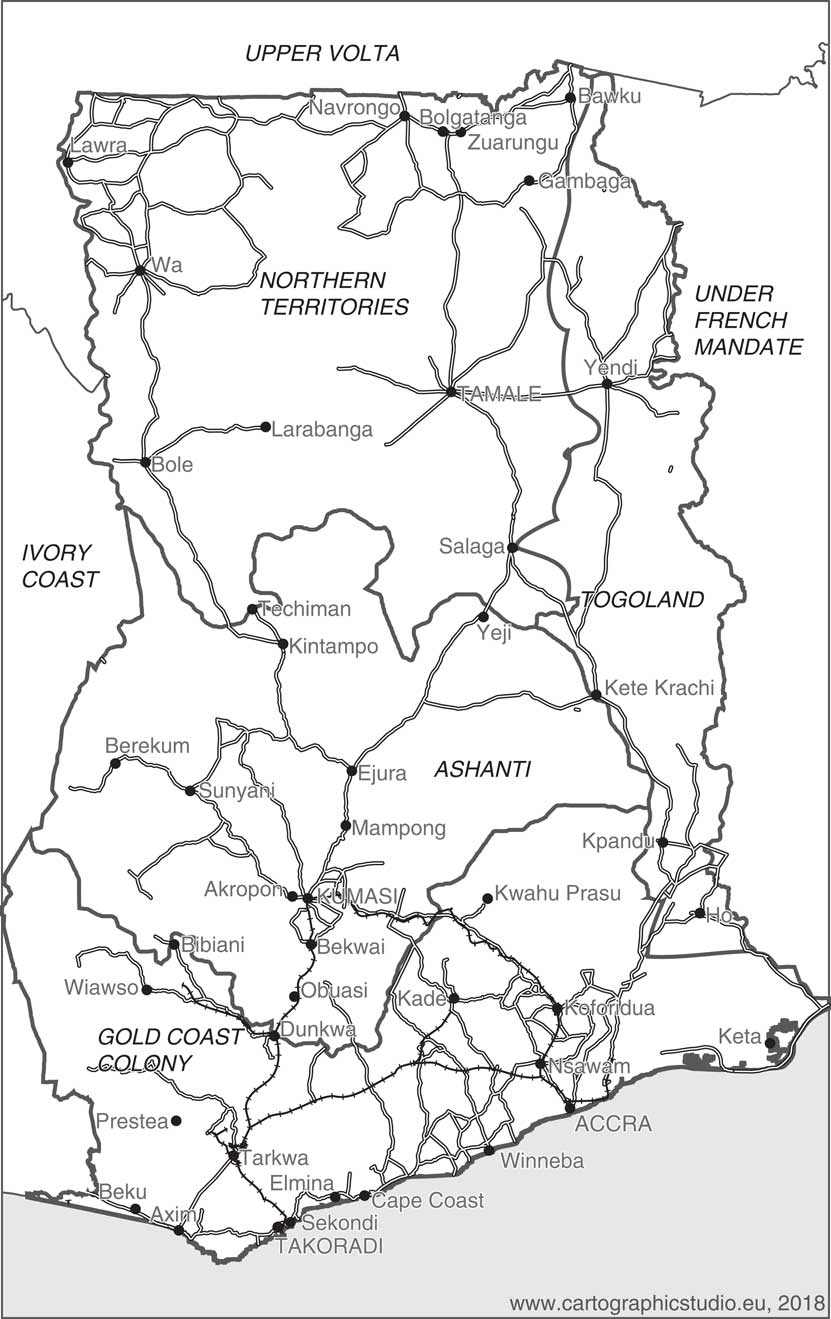

In the Gold Coast, the question of road labour was most pressing in the Northern Territories, where chiefs rather than the Public Works Department (PWD) were responsible for the majority of road works. A vast administrative region north of Ashanti, the Northern Territories represented almost half of the total area of the Gold Coast. According to Bening, a distinguishing feature between the northern and southern areas was the historical prevalence of decentralized communities, or stateless societies, in the North, meaning the absence of a secular local authority such as a chief.Footnote 14 While chieftaincies and secular rule were in many cases an outcome of European intervention in the North, the population accepted chiefs by 1930. Although chiefs carried out colonial orders, their rule was formally not incorporated into the colonial administration.FIGURE 1

Figure 1 Map of the main roads in the Gold Coast, around 1936. Apart from these first class motorable roads, the road network consisted of tarred and untarred second and third class roads.

A recent article by Alice Wiemers focuses on forced labour for road works under chiefs in the Northern Territories form 1920 to 1936.Footnote 15 She contextualizes her analysis in development discourse and also focuses on migration to evade forced labour conditions. Wiemers argues that reclassifying roads as local roads mainly resolved the issue the Forced Labour Convention posed to the system of forced labour, as the convention exempted forced labour in communal service. Yet, the continuation of road labour under chiefs was far more complex. Although chiefs play a central role in her analysis, discussion of indirect rule is absent. The expansion of indirect rule in the Northern Territories was central for labour on roads that were not classified as local, which was the majority.Footnote 16 Of course, the period after 1930 is only a minor focus within Wiemers’s article, which does not allow an in-depth study of the effects of the Forced Labour Convention.Footnote 17 In contrast, this article shows that the reclassification of roads as communal roads was only a partial solution, which did not solve maintenance on public roads, and that the expansion of indirect rule in the North was pivotal for the continuation of road labour under chiefs.

Despite the extensive historiography on indirect rule in the Northern Territories, scholars have paid little or no attention to labour in this context.Footnote 18 Some studies have analysed recruitment for mine labour through chiefs (which was largely unsuccessful). Forced labour for private works falls outside the scope of the present study.Footnote 19 The focus on chiefs’ involvement in labour recruitment for the public sector after 1930 has hitherto been largely overlooked. Likewise, there has been little or no research on the continuation of forced labour after 1930.Footnote 20 This absence corresponds with a wider neglect of forced labour in British colonies.Footnote 21 Historical studies have focused more on colonies where forced labour was violent and blatant, such as in the French and Portuguese colonies. Such studies are often complemented by research on emigration patterns from colonies with exploitative labour policies.Footnote 22 The Gold Coast has become a prominent example of the connection between abusive labour practices in French colonies and labour migration. Forced labour, heavy taxation, and conscriptions caused high numbers of French subjects from the Ivory Coast and Upper Volta, which was administered by the Ivory Coast from 1932 to 1947, to seek waged labour employment in the Gold Coast, where wages were higher and colonial policies more liberal in comparison.Footnote 23

According to Van Waijenburg, French colonies introduced buy-out rates through which the local population could free themselves from the sixty days of forced labour they were obliged to perform per year. As French colonies were particularly interested in making revenue through these buy-out rates, they were fixed along the wage rates for public labour.Footnote 24 This contributed to the labour migration from French colonies to the Gold Coast, where wages were slightly higher. This migration pattern might have been beneficial for the decline of forced labour in private industries, but it did not affect the situation of forced labour in public works, as I will show.

THE ILO AND LABOUR REGULATION IN AFRICA

The reliance on forced labour instead of waged labour is typically considered to be based on economic factors, as forced labour in African colonies was generally unpaid.Footnote 25 The implications of the Forced Labour Convention posed an additional expenditure for governments that were interested in running the colonial operation as cost-effectively as possible. The Great Depression of 1929 had already put economic pressure on colonies, and colonial governments certainly were not keen on increasing expenditure on public works in this context.Footnote 26

A civic debate underlying moral notions of forced labour for public works was also developing. Members of the ILO, such as the director Albert Thomas, held the opinion that colonial administrations had a responsibility to educate indigenous populations about labour, which referred to Western notions of modern civilization, labour ethics, and labour relations. Forced labour under violent conditions would create a negative attitude or even hatred towards the employer and to the work itself, and was therefore detrimental to the colonial educative mission of creating waged labour societies. It was based on this notion that the ILO progressively abolished forced labour for private industries, in contrast to public works.Footnote 27 A central assumption seems to have been that labour exploitation took place in the private sector, whereas coercion in the public sector was educational. The “education” of indigenous populations within the British Empire meant introducing modernization and civilization, which in the colonial mentality was comprised of the European industrial-relations model. Roads were regarded as part of introducing the infrastructure of (industrial) modernity, and hence of civilization.Footnote 28 The Forced Labour Convention gave space to the “educative practices” of forced labour and exempted communal labour that was in the direct local interest.Footnote 29 From the 1930s onwards, British colonies frequently adjusted bureaucratic terminology to bring forced labour into alignment with forced labour regulations. Okia has analysed how authorities continued coerced labour by relating it to “traditional duties” under chiefs or enforcing it as communal labour in Kenya in the period before 1930.Footnote 30 In this respect, state manipulation was very much part of what has been described as the invention of tradition.Footnote 31 Keese has shown how the colonial administration of Northern Rhodesia reacted to the ILO Convention on the Abolition of Forced Labour of 1957 with administrative and legal changes that enabled direct and indirect labour recruitment for road labour through chiefs up to the late colonial period.Footnote 32 For the post-World War II period, Vickery has analysed how forced labour re-emerged in the Rhodesias.Footnote 33 As the convention had a provision for exceptions during emergencies such as war, forced labour was deployed for the construction of military infrastructure as well as for private farm labour.Footnote 34 The British strategically used this search for legal exceptions and the subsequent legal and administrative modifications to fit those exceptions at different points in time in different colonies. In all cases, a shift in labour regulation was enforced on the colony by an external force, be it the ILO or the metropole: the developments in Kenya were connected to Winston Churchill’s prohibition of forced labour for private enterprises.

One of the exceptions specified by the convention was communal labour, which had to benefit the community directly, and was therefore considered a civic obligation.Footnote 35 This regulation is central in analysing the effects of the convention on labour under the chiefs, especially communal road labour, which proved to be a grey area. The definition of “communal interest” is significant. The convention states that any person who had recourse to forced labour had to ensure that the work carried out through such labour was of “important direct interest” to the community and of present or imminent necessity.Footnote 36 The British colonies benefitted by classifying forced labour as communal labour, and therefore labour as such did not have to be remunerated according to market rates.Footnote 37 When chiefs carried out public works on roads exceeding the direct communal interest, cash payment at market rates had to be introduced “as soon as possible”, which seems to be a highly vague temporal definition for a legal text.Footnote 38

The ILO might have based the exemptions in the Forced Labour Convention on their notions of the educational aspects of labour, and the colonial administration adopted terminology that supported the notion that labour was carried out as civic duty, yet references to such educational and civic aspects are scarce in the discussion on the effect of the Forced Labour Convention in the Gold Coast.

THE ILO CONVENTION AND ROADS IN THE GOLD COAST

Before 1930, road works, construction, and maintenance, were carried out as a labour tax in the Gold Coast by men and women. In the colonial mindset, transportation was developed in the interest of the local communities. In addition, colonial officials regarded forced labour for public works as an extension of tributary relationships, as Wiemers argues.Footnote 39 If local communities would not fund the construction through paying monetary taxes, they had to support it with their labour.Footnote 40 Reimbursing chiefs to enable the payment of road labourers was furthermore considered futile, as an excerpt from a 1929 letter by the Chief Commissioner of the North to the Colonial Secretary explains:

[I]t may be said that formerly, when so little money for roads was allowed that it worked out at 5/- per mile up here, it was obviously impossible, if 200 men were employed on one mile of road, to pay each individual from fractions of that 5/-, so of necessity, the Chief received the money, or in some cases the Commissioner would buy a cow with the money payable, and let the men have good food at the end of their period of work; this was the most popular method naturally.Footnote 41

This method of payment certainly suited the colonial administration. The Commissioner continues that as more money was available, all labourers were paid as long as the money lasted, but typically road labour was paid in kind with food, and chiefs received a gift for organizing the labour.Footnote 42 If chiefs were reimbursed for road works, it was their problem if that amount was insufficient to pay for labour. It is difficult to reconstruct what really happened on the local level and whether labourers received some form of remuneration. Ntewusu states that labourers for the construction of the “Great Northern Road” that connected the North to the South for trade were either conscripted, or paid according to the wage index, which was two shillings and six pence per day.Footnote 43 Of course, whether labourers received payment for their work may have also depended on what kind of work they performed and whether they were skilled or unskilled labourers. Road labour was carried out by gangs formed by chiefs, who arranged any required road labour. Officially, the maximum period of forced labour allowed for road labour was six days per quarter year and a maximum or twenty-four days per year, but the colonial administrators’ rather laissez-faire attitude to record-keeping makes it difficult to evaluate how well they adhered to this limit or to what extent forced labour was used.Footnote 44 The official limit of twenty-four days compares favourably with the maximum of sixty days that was specified in most of the French colonies.Footnote 45 FIGURE 2

Figure 2 “Cleaning the road near Abokobi”. Road maintenance on untarred roads involved the regular weeding and trimming of trees and scrubs. Photograph by Rudolf Fisch, Abokobi, c.1899–1911. Basel Mission Archive, D-30.05.033. Used by permission.

Figure 3 “Clearing a tree trunk out of the way”. Road works also included the clearance of fallen trees blocking the road. Photograph by Hermann E. Henking, c.1931–1945. Basel Mission Archive, D-30.63.048. Used by permission.

The internal discussion of forced labour on road works following the ratification of the convention centred on road maintenance, as road construction was stopped, mainly due to construction costs.Footnote 46 The North immediately became the main concern for road maintenance under chiefs. As the Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories Duncan-Johnstone pointed out, the convention had only aimed to regulate forced labour under the chiefs for public works, which, according to him, was limited to road maintenance at that point.Footnote 47 Chiefs carried out extensive road maintenance in the Gold Coast. According to the Colonial Annual Reports of the Gold Coast for the Year 1929–1930, chiefs maintained 4,396 miles of the total of 6,264 motorable miles in the Gold Coast, roughly seventy per cent.Footnote 48 After 1930, the colonial annual reports did not publish the mileage of roads maintained by the PWD and chiefs. Instead, they distinguished between “political” and “native” or “feeder” roads. This change was certainly not arbitrary and was most likely made to avoid drawing too much attention to chiefs carrying out public works. At the end of 1931, the total mileage of motorable roads rose slightly to 6,350 miles, of which 4,225 miles were classified as political roads, 1,955 of which were in the North.Footnote 49 This means that forty-six per cent of all motorable political roads in the Gold Coast were in the North, where the PWD carried out only a small amount of road maintenance.Footnote 50 The convention confronted the British administration with two options: either the PWD should take over road maintenance, or the administration should fully reimburse chiefs for road maintenance at the PWD rate. A PWD rate of twenty pounds a mile per year would have meant a total of £39,100 for the North.Footnote 51

The reclassification of roads partly solved this problem. “Political roads”, which were the most important roads for the colonial economy, were reclassified as “public roads”. “Native” and “feeder roads”, which connected villages to the main roads or other villages and were typically untarred, were reclassified as “local roads”.Footnote 52 The Forced Labour Convention affected the classification of “local roads”, as communal labour was only exempted for work in the direct local interest, and the “local road” classification supported the argument of “purely local” importance.Footnote 53 The question, as always, is whether colonial officials communicated these regulations on the local level and whether local populations were aware of the distinction between the classes of roads and the regulations involved. In the absence of sources that reflect the local perspective, such questions are difficult to answer. However, the colonial administration might have shied communicating information on the regulations at a local level, where awareness of such regulations would undermine the colonial interest.

The reclassification of roads did not occur without a debate amongst colonial officials over the meaning of “purely local interest”.Footnote 54 “Chiefs’ roads” was a term used in colonial communications, but never in official reports. Although it refers to “local roads” in certain cases, “chiefs’ roads” was also used for public roads that were maintained under chiefs.Footnote 55 Historians have frequently emphasized the colonial economic interest in the classification of roads.Footnote 56 The official reclassification of roads came from capitalist motives as well as from the requirements of the convention for communal labour, as only labour on “local roads” was exempted from the Forced Labour Convention.Footnote 57 Following a careful study of the proceedings at Geneva, the Colonial Secretary made clear that:

[…] “minor communal services” (one of the exemptions) does not include work on any roads which serve other than those of “purely local importance”. Work on a road which is clearly a main road “which is of interest to other communities than those performing the work” cannot be regarded as a “minor communal service”.Footnote 58

This meant that only roads connecting villages to main roads were considered of “purely local interest”, and only such roads could be maintained by unpaid communal labour.Footnote 59 Many of these local roads, however, had economic importance beyond the local community, as they were central in the trade of agricultural produce from the farms to the economic centres.Footnote 60 In the Northern Territories, roads gained additional economic importance for labour migration, reflecting the area’s increasing role as a labour pool for the southern industrial areas.Footnote 61

Wiemers’s analysis of the continuation of forced labour in the Northern Territories focuses on the reclassification of roads as local.Footnote 62 Although administrators used this strategy, not all roads could be classified as local, and the majority continued to be classified as public roads. Road maintenance on these public (or political) roads was a much bigger issue for colonial officials, as the following extract from a letter by the Governor to the Colonial Secretary shows:

Please ask the A.G. [Attorney-General] to advise what exactly will be our obligations, on and after 3rd June, 1932, in respect of communal labour (i.e. labour called out by Chiefs and at present remunerated only by small “dashes”) used on the maintenance of “political” roads (other than roads of “purely local importance”).Footnote 63

3 June 1932 marked the date by which the Gold Coast had to follow the regulations of the Forced Labour Convention. This quote shows that the colonial administration was concerned with the implications of the convention for local and public roads. The Governor uses the term “communal labour” to refer to all labour called out by chiefs, yet as political roads are not roads in the direct interest of the local community, labour on it cannot be “communal labour”, according to the Forced Labour Convention. The Attorney General responded to the enquiry of the Colonial Secretary to state that there was no loophole, which meant a necessary introduction of “[…] of wages to communal labourers who have hitherto (in 99 cases out of a 100) cheerfully maintained the roads for a small ‘dash’. Of course the Chiefs won’t be able to do this till we can give them authority to impose regular direct taxation on their people and that proposition can’t be hurried […]”.Footnote 64 One might wonder how labourers expressed the cheerfulness with which they maintained roads for little or no remuneration; chiefs frequently complained to commissioners about reluctance amongst their subjects to perform forced labour.Footnote 65 The Attorney General immediately points to chiefs for the reimbursement of labour and the necessity of introducing direct taxation to enable them to do so. From the perspective of the colonial government, costs for road maintenance had to be avoided by all means. Initial considerations to transfer road maintenance to the PWD were dismissed as soon as it was calculated that this would cost £150,000 per year for the whole colony, as colonial officials claimed that there were no funds available.Footnote 66 The depression of 1929 continued to affect colonial economies, which was certainly the framed discussions on the availability of funds. Shaloff claims that the unsuccessful introduction of an income tax directed at higher-income earners in urban areas was a direct outcome of the Great Depression.Footnote 67 Even though the introduction of direct taxation cannot be taken out of the context of the exacerbated economic pressure of the depression, no source explicitly refers to this factor in relation to the introduction of direct taxation after 1930. Cost-efficient operation of the colonies was vital for the British Empire. As road maintenance had been a cost-free operation for the colonial government hitherto, the colonial government would have been unlikely to take over the financial costs of it in the absence of the depression. Nevertheless, the depression contributed to the colonial aim of keeping the status quo concerning road labour.

ADMINISTRATIVE FUNCTIONS AND INDIRECT RULE

The Forced Labour Convention not only meant that forced labour exceeding communal interest had to be reimbursed, it also regulated under which conditions chiefs could access forced labour for public works. The convention ruled that only those chiefs who exercised administrative functions could have legal recourse to compulsory labour, and that the permission of a “competent authority”, which referred to a colonial official, was required.Footnote 68 Within the discussion on road maintenance under chiefs, the question of exercising “administrative functions” became central.Footnote 69 The correlation between the Forced Labour Convention, road labour, administrative functions of chiefs, and indirect rule in the Gold Coast became of immediate interest to the colonial government, as this quote from the Acting Colonial Secretary demonstrates:

The question now arises: Do Chiefs in the Gold Coast exercise administrative functions under our present system of rule? If they do, this Government is merely pledged to abolish progressively the use of unpaid labour on roads during the next five years. If, on the other hand, they do not, then, in accordance with the terms of the first clause of Article 14 [of the Forced Labour Convention], this Government will, as from the 3rd June next, have to insist on the Chiefs paying wages, at full market rates to the communal labourers or allow the roads to fall into disrepair, as it would be obviously prejudicial to the endeavours to establish indirect rule for the central Government to take over the maintenance, even assuming that funds were available for this purpose.Footnote 70

The colonial debate about “exercising administrative functions” centred on the definitions given by the Forced Labour Convention and the Road Ordinances in existence in the Gold Coast.Footnote 71 Officials concluded that the chiefs did not exercise administrative functions meaning “[…] a Chief really carrying out the running of his own country under the supervision of administrative officers”,Footnote 72 and therefore could not have recourse to compulsory labour.Footnote 73 This regulation was crucial for the implementation of indirect rule, as chiefs had to rule within the colonial administration to access forced labour for road maintenance. After examining the system of rule in the Northern Territories, colonial officials agreed that chiefs did not exercise administrative functions at that point. It was in this context that the Colonial Secretary stated that chiefs should be invested “[…] with administrative function and with a source of revenue sufficient to enable them to exercise such functions, among which will be the maintenance of roads” by 1933 at the latest.Footnote 74 The regulation of administrative functions in the Forced Labour Convention made the introduction of indirect rule in the Northern Territories inevitable. Investing chiefs with administrative functions needed execution on the legislative and administrative levels. Concerning changes in legislation as a consequence of the Forced Labour Convention, colonial officials discussed the possibility of passing a law directly relating to that aspect of the convention. They hesitated because such a law would have drawn direct attention to the issue of forced labour, which was certainly unfavourable for the colonial government.Footnote 75

For the Gold Coast government, the investing of the chiefs with administrative functions had two aims in terms of labour: 1) it gave the chiefs legal access to compulsory labour, and 2) it provided them with funds to pay for labour on public roads. Two institutions were central in achieving those aims: the “Native Treasuries” to generate revenue and the “Native Courts” to both give chiefs access to penal labour and also explicitly to punish those refusing to perform communal labour.Footnote 76 Such courts were also important for the legitimisation of “Native Authorities” within the colonial Government and the execution of colonial law. Courts in the Gold Coast were not an “invention” of the British; “Native Courts” referred specifically to those that had been established within the colonial administration as part of indirect rule and served to legitimize the chiefs’ position within the colonial Government.Footnote 77

Although direct taxation was predominantly discussed in terms of cost and expenditure, Secretary of Native Affairs Jones argued for the introduction of direct taxation in the context of the educative and civilizing mission of colonization:

With regard to roads, there exists both the necessity and justification for direct taxation. The future of the cocoa industry depends on cheap transport as, with the price of cocoa the present figure, the cost of head loading for any except the shortest distance would exceed the profit which the producer obtains. Our present system of roads must be maintained if the Gold Coast is to compete successfully with other cacao-producing countries. Herein lies the necessity and surely it is only just that the people, on being relieved of the maintenance work, should defray its cost.Footnote 78

This quote reveals the colonial ideology: the introduction of the Gold Coast to the global economy is implicitly portrayed as the “communal interest” that the individual has to support either with labour or with tax. Whether the said individual is directly profiting from the cocoa industry was either irrelevant, or determined by the colonial government.Footnote 79 Ultimately, Jones changed his opinion, and as Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories recommended in 1935 that the colonial Government make funds available for the payment of labour.Footnote 80 One explanation for Jones’s change of heart might be that the local experience Jones gained as Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories influenced his perspective, in contrast to his position as Secretary of Native Affairs. Such a change as the result of experience would not be uncommon, as northern district and regional commissioners frequently advocated for policies that took local perspectives and experiences into account.

The notion that relieving people from road labour would justify the introduction of taxation on a moral basis is also particularly intriguing, especially considering that it was the colonial government who burdened the people with that labour in the first place. In addition, the introduction of direct taxation for the payment of road labour did not result in people being relieved from road labour. Instead, they had to pay direct taxation and still carry out road labour. The people noticed this development, and some were reluctant to perform communal labour for their chiefs once they had to pay taxes.Footnote 81 For the colonial administration, funds for road maintenance should logically be extracted from the same population that also carried out road labour. The colonial government of Northern Rhodesia deployed the same strategy, in which Native Treasuries were also set up to transfer financial obligations for road labour to chiefs.Footnote 82 Unsurprisingly given the context, local authorities rather than colonial officials collected taxes.Footnote 83 However, colonial officials in the Gold Coast anticipated that chiefs as well as the local population would oppose the introduction of direct taxation. After all, the Gold Coast was the prime example of opposition to direct taxation, as attempts to impose taxes before 1930 were unsuccessful due to local resistance, especially in the North.Footnote 84 This previous experience of unsuccessful introduction of direct taxation has also caused colonial officials to be sceptical about direct taxation.Footnote 85 Direct taxation was not an indigenous institution in the North, and the sentiment was that people would not accept its imposition by strangers. Based on this history of taxation failures, the District Commissioner of Yendi was sceptical about a new attempt:

My first impressions are that this policy is being forced on us apparently without consulting Government and certainly not consulting the Chiefs and people concerned. The Chiefs and people of the Northern Territories in my opinion will be strongly opposed to the abolition of “prestation”.Footnote 86

The term “prestation” for labour tax was mainly used in the context of French colonies. This use remains, however, an isolated case and is therefore difficult to evaluate. The commissioner notes that the policy was forced upon the colonial government of the Gold Coast just as much as on the chiefs and the local population, and that none of the affected actors support the policy. Of course, the mindset that forced labour was in the local interest, could in return justify the continuation of the forced labour. The District Commissioner continued by stating that the convention should only be introduced with modification in the North, since the local financial situation would not allow a full introduction, and “[…] furthermore that its introduction at present is contrary to the wishes of the people themselves”.Footnote 87 In the Nigerian colony, the introduction of direct taxation through chiefs had led to mistrust of the local population towards the chiefs and in some cases also ended in violence. Such a development was certainly not in the interest of the development of indirect rule, and the experience of Nigeria might have informed the opinion of the District Commissioner.

Not only the introduction of direct taxation, but also the enforcement of forced labour on road maintenance elicited criticism of colonial officials. The Attorney General commented in the discussion on administrative expansion of indirect rule and forced labour:

For the Government of the Colony to compel the inhabitants of a district to keep roads in repair appears scarcely the practical expression of a desire to leave them to govern themselves nor is that ideal brought any nearer by effecting that compulsion by imposing it upon the Chief and enabling him to transfer it to the community.Footnote 88

Colonial officials rarely explicitly questioned the protective character of the colonial administration. The Attorney General made it clear that the duty of road maintenance was forced upon the local communities by the colonial administration without consulting local authorities. Of course, such a statement would hardly have been made outside of confidential correspondence, due to the implications it held for forced (or communal) labour and the government’s methods of legitimizing it. The Attorney General’s comment also emphasizes that indirect rule was introduced in the pursuit of colonial policies, specifically to enforce road maintenance, and not because the colonial administration considered giving chiefs self-rule as a desirable objective in itself.

When the introduction of a subsidy of road maintenance under chiefs in the North was discussed in 1935, the colony decided to pay, for the total of 1,460 miles of political roads in the Northern Territories, an average rate of little over five pounds per mile per year. The reason for such a low rate was the assumption that fifty per cent of the labour used for road maintenance was expected to come from forced labourers and therefore would not need to be paid.Footnote 89 The colonial government thereby actively promoted the continuance of forced labour on public roads and put economic pressure on chiefs to procure forced labour. As maintenance of public roads was not exempted from payment unless it was penal labour resulting from a court’s conviction, this calculation indicates that the colonial administration planned to abuse the convention through chiefs.

Using chiefs to maintain roads through communal labour does not mean that the chiefs’ agency was completely subjugated to the colonial administration. Mamdani claims that without “Native Courts”, any “Native Authority” would have been “emasculated as an active agent”.Footnote 90 In the Gold Coast, a “Native Authority” was never an individual, but a group of people of which the chief was one member. Although chiefs in the Northern Territories did receive more power within the colonial administration, their legitimacy relied heavily on their populations. Chieftaincy itself was an institution that predated the colonial administration in the Gold Coast, but had been introduced by the British colonial government to decentralized communities in the North. Although in those cases colonial intervention certainly occurred, to install chiefs that were not accepted by their respective communities was futile. In some cases, the colonial government even reshaped spiritual leaders into chiefs with secular responsibilities, as the authority of chiefs was affected when legitimacy was not derived from the population.Footnote 91

Whereas historiography has focused on the dominating aspect of indirect rule, more recent research has shown a reality focusing on chiefs’ agency and their search to consolidate power within the colonial administration. The difficult negotiations and planning involved in the introduction of indirect rule reveal that local authorities were not powerless, as Grischow shows.Footnote 92 The fact that the colonial Government introduced indirect rule to continue forced labour in pursuit of their economic interest does not indicate that chiefs were not also able to pursue their own interests or those of their community. Local authorities actively petitioned the colonial government to hand over road maintenance, with the intention of setting up a “Native Treasury”.Footnote 93 Some chiefs even introduced payment for communal labour or replaced it altogether with waged labour financed through “Native Treasuries”.Footnote 94 This development was very much a local initiative and more an unintended outcome rather than the result of colonial enforcement.

REPORTING (AND CONCEALING) FORCED LABOUR TO THE ILO

The Gold Coast Government was required to submit annual reports on forced labour and the application of the convention to the ILO. Those reports and the colonial discourse on what and how to report illustrates of the colonial Government’s approach to forced labour. Although the reports stated that forced labour was carried out as communal labour, the existence of illegal forms of labour as defined by the convention was simply denied. As the Colonial Secretary points out in a circular to the Chief Commissioners: “The reports from this Government have so far been of the nature of a denial of the existence of forced labour and no details have been given as to the machinery by which illegal forced labour has been brought to an end.”Footnote 95 Other colonial officers pointed out that it would not be difficult to determine if the absence of illegal cases of forced labour in reports was due to complete adherence to the convention “[…] or complete disregard of the regulations by the Chiefs […]”.Footnote 96 This wording does not explicitly acknowledge the existence of illegal use of forced labour by chiefs, yet reflects an awareness that exploitation probably took place. This obfuscation supports the assumption that the colonial government turned a blind eye to forced labour as long as it was not perpetrated directly on their behalf and was ultimately to their benefit. The colonial Government was reluctant to fully support the departure of a system of forced labour, and rather forced chiefs to make use of forced labour. Subsequently, the colonial Government was able to point to chiefs when questions of forced labour abuses for public works arose.

The colonial administration was aware of cases of forced labour abuses by chiefs. Before the introduction of indirect rule, it was customary for the local population to help with the upkeep of their chief’s compound and farm. As the chiefs accommodated visitors on behalf of the village, this work was regarded less as a private service and more a service to the palace. Certain chiefs began to exploit this system in the 1930s and tried to declare it a legal obligation.Footnote 97 Unfortunately, there is no record of whether the chiefs who abused the forced labour system were taken to court or what kind of repercussions they faced. This labour on chiefs’ farms continued with the knowledge of the colonial officers, who reported that the labour was voluntary and was rewarded with food and drink.Footnote 98 It cannot be said why the colonial government was not concerned with such forms of forced labour, but as such forms were not directly connected to the colonial administration, officials might not have perceived them as their issue. This indifference was also applied road maintenance, as the government transferred this work formally to chiefs.

The first report on the application of the Forced Labour Convention to the ILO in 1932 did not report any figures on forced labour. It was stated that, especially for the Northern Territories, it was impossible to document compulsory labour (as communal labour) used for road maintenance.Footnote 99 In a letter to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Governor of the Gold Coast stated that 1,250 men worked an average of six days per quarter year in the Northern Territories and in the North of British Togoland on road maintenance.Footnote 100 This statement proves that it was not only possible to record numbers, but also that such information was transmitted to England, though not relayed to the ILO. Another report on forced labour from the Chief Commissioner of the Northern Territories on the period from 3 June to 30 September in 1932 reports a total of 5,354 man-days for the Mamprusi and Dagomba District alone, further recording that even though a “small amount” was called out in the Wa and Lawra-Tumu District, no statistics were available.Footnote 101 These statements raise the question of why numbers were recorded in some districts but not in others. The absence of a uniform regulation on the observations of forced labour through commissioners befits the colonial government’s disinterest in practices of forced labour. By omitting the available data from the report to the ILO, the British certainly tried to conceal the extent of forced labour. This contrasts with other British colonies, like Kenya or Tanganyika for example, that submitted fairly detailed reports on the application of convention regulations and of figures for cases of forced and communal labour.Footnote 102 The omission of specific data was therefore specifically the outcome of the Gold Coast government’s policy, and not a general strategy pursuit by British colonies.

The reports from the Gold Coast also neglected the practical and legal regulations through which a person from whom forced labour was exacted could recover freedom and obtain compensation. It was the absence of such a reference that led the committee of the ILO to begin “to smell a rat”.Footnote 103 Indeed, the labour legislation did not specify a procedure for an individual to recover his or her freedom or to claim compensation for unpaid forced labour. The only proceeding in place recommended that the person concerned should report to the District Commissioner, who would then investigate and take the necessary measures on the matter.Footnote 104 However, colonial officials were quite sceptical about the usefulness of this provision: “[…] whether a native, in say, the N.Ts. who has been illegally forced to work would have either the knowledge or the hardihood to bring the offender before the court so as to recover his freedom and obtain compensation is open to doubt”.Footnote 105 What measures did the colonial government undertake to inform the population of the Northern Territories about labour and human rights? While the legal and administrative system was meticulously planned to comply with the convention to enable the continuation of road maintenance, a legal system or any sort of procedure for illegal cases of forced labour to support the person was not discussed. This certainly does not indicate a high level of commitment to the abolition of illegal cases of forced labour.

The colonial government did decide to conduct an official investigation into forced labour abuses in private enterprises in an attempt that can only be regarded as a tactic to divert attention from illegal forced labour in public works: “No seriously embarrassing abuses are likely to come to light but such a survey would fortify our position and give sound basis for annual reports for some time to come.”Footnote 106 The incentive of such an investigation was not a serious interest in ending such practices, but rather the credit the investigation would bring to the Gold Coast colonial government in complying with the convention. The colonial government of the Gold Coast was very strategic in how it reported forced labour and how it diverted attention on that matter away from the colonial administration to private industries and chiefs.

CONCLUSION

The colonial discourse reveals a blatant search for a legal and administrative “loophole” to continue forced labour. Indirect rule was introduced in the Northern Territories to continue the system of road labour under chiefs, while remaining in compliance with the ILO convention. Unpaid communal labour maintained local roads that were purely of local interest, and indirect rule gave chiefs the administrative functions and the means to make revenue through direct taxation to carry out road maintenance of public roads. As a result, the introduction of payment for road labourers became a matter for the chiefs on the local level that barely interested the colonial government. The colonial administration enabled chiefs with the means to pay wages, but did not control whether chiefs actually did so. In a twist of logic, forced labour therefore became formalized after 1930.

No actual departure from the existing system resulted following the convention. The colonial state had simply institutionalized it. Chiefs played a central role in the change in social relations after the convention as the administrative expansion of indirect rule in the North effectively gave them more powers over their subjects within the colonial bureaucracy, but they were also transferred the responsibility of road maintenance through which the colonial administration could “relieve” itself of any direct contact to forced labour. Even though the Forced Labour Convention did lead to a shift in labour regulations, labour relations de facto remained the same, at least from the labourers’ perspective.

According to the taxonomy of labour relations of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, the individual who performed road labour under chiefs was as much an obligatory labourer before the Forced Labour Convention as after, unless chiefs enforced the shift from obligatory labourer to wage earners. The convention did not abolish forced labour for public works, but instead regulated it. One change for the labourers was that in addition to performing communal labour, they now had to pay taxes too. Whereas coercion was applied in the form of communal labour on local roads, taxation was introduced to pay for road labour on public roads in line with the convention’s regulations, yet colonial officials continuously used the term “communal labour” for labour on public roads.

This systematic analysis of the discussion on colonial policymaking shows that the colonial administration was little concerned with the social aspects of forced labour and preferred the continuance of existing methods. Illegal forms of forced labour continued to exist in British colonies despite the ratification of the Forced Labour Convention. Much as in other British colonies like Northern Rhodesia and Kenya, the Gold Coast government applied an administrative system as “hidden strategy” to maintain labour relations in response to a enforced shift in labour regulations by an external body that was aided by a reformulation of terminology for the continuance of forced labour. Although practices of forced labour may not have been as blatant and violent as in other colonies, they nevertheless have to be included in research on forced labour in the history of British colonialism and unfree labour.