“The eyes of the world are on the Copperbelt tonight”, proclaimed Jack Hodgson, a shop steward of the white mineworkers’ union who would, many years later, become a founding member of the armed wing of the ANC (Umkhonto we Sizwe), standing before a riotous crowd of white miners from Roan Antelope Mine in March 1940. Despite his pleas, the meeting was unable to come to a decision over strike action and dissolved into a series of brawls and acrimony.Footnote 1 Days earlier, white mineworkers had walked out at nearby Mufulira and Nkana mines, the first wildcat strikes that marked the beginning of several years of industrial unrest among the white workforce on the Copperbelt.

Hodgson’s rhetorical flourish was an exaggeration, but wartime demand for copper had brought the Copperbelt in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) to global attention. This article explores the 1940 strikes and the subsequent deportation of two leaders of the white mineworkers’ union in 1942. These events offer a window into the world of the primarily English-speaking labour diaspora that linked mining centres around the world. The international links of the region’s transient white population are important in two senses. Firstly, they help explain the powerful combination of industrial militancy, political radicalism, and racial exclusivity that came to dominate the Copperbelt – a combination that is captured, to a certain extent, in Jonathan Hyslop’s concept of “white labourism” which was coined with the situation before World War I in mind but which, as I argue, can also be applied to later periods.Footnote 2 Secondly, these links and contacts had a practical dimension and were utilized to try and mobilize support for the demands of these mineworkers across the world of European labour.

In his 1999 article, Hyslop uses the mass demonstration in London in 1914 provoked by the deportation of white trade unionists from South Africa to explore the idea of an international white working class not composed of discrete national entities. This class was tied together by flows of white migrants between settler colonies and dominated by an ideology of white labourism, where a critique of exploitation was intricately linked to racism. Hyslop locates the highpoint of this ideology in the years prior to World War I, and elsewhere argues that across the world “the 1920s arguably marked the onset of a period in which working-class people and movements were increasingly nationalised”.Footnote 3 This article, however, drawing on the reaction to another deportation of white trade unionists in 1942, will illustrate that these links and the ideology they helped generate endured some three decades later.

Subsequent criticism of this concept, most recently by William Kenefick in this journal, has focused on the conflation of white labour with white labourism by Hyslop. This critique centres on the extent to which “non-racialists and anti-segregationists did mount a serious challenge to the prevailing ideology of white labourism” in South Africa through the dissemination of radical and revolutionary ideas.Footnote 4 Kenefick argues that this questioning of white labourism was disproportionately influenced by radical Scottish migrants. Hyslop, in turn, has replied that the challenge posed by these radical opponents was ineffective and garnered little mass support.Footnote 5 In his article, Kenefick draws on the work of Lucien van der Walt, who has criticized Hyslop for ignoring other currents in the white labour movement in his original formulation of white labourism, and stresses that “the politics of the white working class in southern Africa were not homogenous”.Footnote 6

This article takes up the issues involved in these debates but approaches them in a slightly different way. The politics of the white workforce on the Copperbelt were certainly not homogenous as there were alternative radical and internationalist currents which commanded significant support in the 1940s. The radicals working in the mines, however, made little attempt to challenge the substance of white labourist ideas or the racialized segregation of labour, and were seemingly uninterested in doing so. Their struggle was with moderate elements within the union and with the mining companies. Indeed, it was these radicals who, while firmly identifying the mining companies as their primary opponent and, as will be shown later, without resorting to an openly racist rhetoric, pressed for the introduction of a formal industrial colour bar, alongside a closed shop and wage increases. On the Copperbelt at least, radical and internationalist components of the white labour movement sat within a framework of racial exclusivity, which was tacitly accepted while the interests of white workers were defended in a militant language.

There are, however, limitations to the applicability of the notion of white labourism to the Copperbelt. Hyslop framed white labourism as being partly about a claim to citizenship and rights, arguing that: “[T]here was a strong stand of politics in which white labour activities staked their claim to political inclusion on the basis of whiteness. Their assumption was often that government and capital were failing to recognize them as white imperial subjects.”Footnote 7 This dynamic was absent on the Copperbelt in this period. White mineworkers did not, for the most part, make claims for political inclusion or make claims for higher wages and better treatment on the basis of their “whiteness”. Claims were made on the basis of class and on the perceived profits of the mining companies, with the implicit assumption that Africans were not part of this working class. This stance might thus be best described as “passive white labourism”.

This is connected to the way in which white labourism was articulated in this period. The kind of overt racist language used by white labour representatives in South Africa was studiously avoided.Footnote 8 Radical white mineworkers on the Copperbelt, as will become evident in the detailed account of events below, used the language of internationalism, trade unionism, and class to appeal for support across the English-speaking world, and saw no contradiction in using this language to make de facto racialized claims on the profits of copper production. This had a lasting impact in the postwar period, when those involved in the struggle to retain the colour bar would strenuously avoid referring to “Europeans” or “Africans”, and instead stress the need to avoid being “undercut” by “cheap labour” – terms with international currency.Footnote 9

Despite the considerable literature about the region, “academic investigations of the Northern Rhodesian copper mining industry”, as Ian Phimister has noted, “have hardly looked at white miners at all”.Footnote 10 Moreover, the scattered references to white miners in this literature tend to echo the arguments of many contemporary accounts of the white workforce, which seek to explain, or blame, white industrial militancy on the Copperbelt on the spread of attitudes from the South African Rand northwards.Footnote 11 Such explanations are unsatisfactory, as events on the Copperbelt in this period can be better explained by the international movement these white mineworkers and their union – the Northern Rhodesian Mine Workers’ Union (NRMWU) – saw themselves as part of and reached out to.

The main exception to this has been Phimister’s 2011 article, which is specifically about the Copperbelt’s white mineworkers. However, Phimister primarily discusses the 1950s and focuses on the lavish lifestyle of white mineworkers, the company’s efforts to remove the industrial colour bar (and the workers’ resistance to that), and the corporate policies of the mining companies. In many ways, the white mineworkers’ struggle in the 1940s discussed in this article form part of the background to Phimister’s account, as it was these struggles which secured the high wages enjoyed in the 1950s and brought about the introduction of a colour bar. Phimister’s analysis, however, does not devote much space to the international links of these white mineworkers, apart from a brief section on links with mining unions in South Africa.Footnote 12

The importance of the international dimension of the labour movement in southern Africa has been increasingly recognized.Footnote 13 This article seeks to add to this general argument, focusing on white labourers on the Copperbelt whose politics, “as those of many other groups of white workers across the region”, were unsurprisingly “deeply shaped by foreign models”.Footnote 14 This was perhaps even more the case on the Copperbelt as virtually none of the white workforce had spent significant time in Northern Rhodesia before joining the mines. The beginning of large-scale mining operations in the late 1920s required a large amount of skilled and semiskilled labour, both of which were in short supply in Northern Rhodesia. The mining companies were unwilling to provide the resources to train African workers, yet the settler population of the territory was tiny – estimated at only 5,581 in 1926 – and few of the men there had the necessary industrial skills or experience.Footnote 15 The mine managements generally took a dim view of the quality of available local white labour. At Roan Antelope Mine, the men recruited locally were “usually wasters”, “careless”, and across the territory “the white labour is uniformly poor”.Footnote 16

LIFE AND LABOUR IN A “PREFABRICATED” MINING COMMUNITY

With local labour not available, the companies sought to recruit and attract white labour from mining camps across the world. Subsequent company publications detailing the biographies of retiring employees give a sense of where this labour came from. For instance, an article on twenty-four men who retired from Mufulira Mine in July 1953, and had mostly arrived on the Copperbelt in the 1930s, reveals that, between them, they had worked in England, Scotland, South Africa, Canada, the United States, New Zealand, Southern Rhodesia, Congo, Tanganyika, and India, and tellingly does not highlight this as something unusual.Footnote 17

The white workforce these men joined was divided into two components: a daily-paid section and a monthly-paid staff section. Staff positions included clerical workers, administrative personnel, professionals such as geologists and chemists, low-level managers along with supervisors of white labour, shift bosses, mine captains, and plant foremen. The daily-paid section encompassed almost all skilled and many semiskilled jobs on the surface and underground. The daily-paid men were mostly either graded as artisans – boilermakers, blacksmiths, carpenters, electricians, and fitters – or semiskilled operators – pipefitters, riggers, cage tenders, and banksmen – and included jobs necessary for the basic functioning of the mine such as winding engine drivers, shaft-sinkers, and rock-breakers. Many daily-paid men also had a supervisory role for a “gang” of African workers who did most of the manual work. Some daily-paid workers formed a union in 1936, but it was small and ineffective until 1940. The terms of the union recognition agreement also prohibited them from recruiting or representing the monthly-paid mines staff, who instead formed a staff association in 1941.

Together, the staff and daily-paid sections comprised around 11.3 per cent of the total workforce in 1941, with 2,052 daily-paid workers and 1,046 staff employed in the four Copperbelt mines.Footnote 18 Significantly, this was a higher proportion than many other mines in the region. Directly across the border in Belgian Congo the vast opencast mines operated by Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK) provided a proximate and seemingly pertinent example for both mineworkers and mine managers on the Copperbelt. UMHK had developed a very different labour policy and employed only 982 white mineworkers in 1941, just 5.7 per cent of the total workforce, with African workers undertaking jobs done by Europeans on the Copperbelt for a fraction of the wages.Footnote 19 However, in both the Katanga and Copperbelt mines it was African mineworkers who carried out the overwhelming majority of manual work underground and on the surface: working as labourers, drillers, preparing blasting, carrying tools, removing blasted ore, lashing, operating grizzlies,Footnote 20 carrying out minor repairs, etc. There were also higher-status jobs which involved less manual labour including “boss boys”, who supervised African labour, or lower-level clerk jobs.

The cleavage in the workforce was replicated in the Copperbelt towns as housing was segregated between European and African workers.Footnote 21 The towns were actually split into four unequal parts: the European and African townships were themselves divided into a mine township and a government township. European mineworkers and their dependents dominated the European townships, which were entirely separate from the African townships. Among a total white population of 8,574 in the Copperbelt towns in 1946, 3,246 (38 per cent) of them were directly employed by the mines.Footnote 22 In turn, their numbers were dwarfed by the African townships.

The townships were alike in name only. From the mid-1930s, thousands of small, high-density mud-brick and concrete huts were constructed to house an African workforce which numbered over 27,000 by 1941, plus tens of thousands of women and children, along with a smaller number of three-bedroomed houses for senior married African workers built in the 1940s.Footnote 23 Mine housing for white employees had rapidly improved during the 1930s from corrugated iron huts and hostels to well-appointed bungalows with gardens, though the increase in the white workforce during World War II generated some problems with overcrowding.

All mining housing was, however, grouped closely around the mines so the plants and shafts were within walking distance. The mining townships also remained the private property of the mining companies. Lewis Gann recognized this as being modelled on the “American system of ‘company towns’”, where people could not live without permission of the management.Footnote 24 This similarity to American company towns is perhaps unsurprising, given that it was American capital, American mining companies, and American mining engineers that played a major role in the initial development of the Copperbelt.Footnote 25 Following the discovery of commercially viable copper deposits in the early 1920s, the Copperbelt was rapidly divided up by two mining companies: the Rhodesian Selection Trust (RST) and Rhodesian Anglo American (RAA). By 1930, other would-be competitors had been bought up or squeezed out, a dominant position which would remain unaltered until the late 1960s.Footnote 26 RST was based in London but was primarily staffed and financed by Americans and operated Roan Antelope and Mufulira mines while RAA was a subsidiary of Anglo American, a South African mining conglomerate, operating Nkana and Nchanga mines.Footnote 27

These companies had an international outlook and consciously modelled wages, working conditions and working practices for the Copperbelt mines on mining regions elsewhere in the world. White miners and managers arriving on the Copperbelt could slot themselves into what were, in many ways, very familiar circumstances.Footnote 28 The mining camps on the Copperbelt can be compared to “prefabricated communities”, a notion coined by James Belich for the crew culture of New Zealand, which he explains as being like: “a new school or a new sports team. The place and people are different, but they duplicate your previous experience; teachers and coaches, desks and balls, curricula and game plans, formal positions and rules, informal customs and folklore.”Footnote 29

Along with their industrial skills, these men brought with them ideas and traditions from the international labour movement, and retained links with the regions they had come from. However, the first efforts to form unions among the daily-paid workers from the early 1930s were abortive, primarily because the workforce was highly transient. There was an attempt to form an Industrial Workers’ Federation in 1934, followed by failed efforts to establish a South African Mine Workers’ Union (SAMWU) branch – scuppered when eagle-eyed RST board members spotted that the SAMWU constitution prohibited external branches – before the NRMWU was founded in October 1936.Footnote 30

The recognition agreement the NRMWU signed with mine managements was restrictive and left the union unable to pursue its demands effectively.Footnote 31 This weakness aggravated internal feuds, and the union went through four general secretaries in three years. The most damaging row came in August 1939 when the union split following a dispute over union finances and the failure to get a sacked American miner reinstated at Roan Antelope. The Roan branch, the largest in the union, left and formed the rival Roan Mine Workers’ Federation. At the onset of World War II, the union was bitterly divided, heavily indebted and its survival was in doubt.Footnote 32

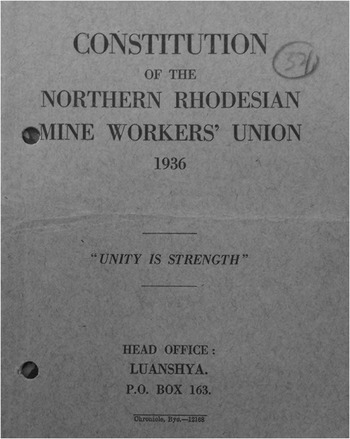

Figure 1 Original constitution of the NRMWU, 1936.Zambia National Archives, Lusaka, SEC1/1376, Constitution of the Northern Rhodesian Mine Workers’ Union, 1936.

This position was dramatically altered by the war. The Copperbelt was the only major supply of copper within the British Empire and so it became absolutely crucial for the British war effort, with Raymond Dumett arguing that “it is unlikely that the British could have stayed in the war” without supplies from Northern Rhodesia and South Africa.Footnote 33 The Ministry of Supply bought the entire Copperbelt output – which peaked at 247,000 long tons in the critical year of 1942 – at a fixed price, and by 1945 Northern Rhodesia was supplying nearly 68 per cent of Britain’s copper supplies.Footnote 34 This placed the white mineworkers in a strong position, provided that they were willing to disrupt the war effort. The war also altered the situation in another sense. On 6 September 1939, the colonial administration issued new emergency regulations prohibiting all male British subjects working in the mining industry from leaving Northern Rhodesia without a permit, which was very difficult to obtain.Footnote 35 Men unhappy with conditions on the Copperbelt could not leave. They were now stuck for the duration of the war.

WILDCAT STRIKES IN MARCH 1940

In early 1940, a network of militants among the white workforce decided to utilize the opportunity presented by the war to settle longstanding grievances over wages and working conditions and to improve their bargaining position permanently. General disaffection with the union allowed this informal group to circumvent the official leadership, push them aside and transform the situation by reinvigorating the union. In February 1939, for instance, an NRMWU branch meeting in Nkana was informed that only 23 per cent of the 689-strong daily-paid workforce on the mine was in the union.Footnote 36 By May 1941, membership had risen to around 80 per cent at Nkana, and the situation in other mines was similar.Footnote 37

The weakness of the union leadership and its lack of control over the daily-paid workforce were evident from the outset of the dispute which started in March 1940. On 15 March, a mass meeting at Mufulira shouted down the local union-branch chairman and formed a committee of action in its place.Footnote 38 Disavowing the recognition agreement – which stipulated that negotiations and conciliation had to take place before a strike – the meeting placed a list of demands before the Mufulira management and announced that a strike would take place within twenty-four hours if they were not met. The committee of action gave a blunt statement to the mine manager Robert Peterson: they were not prepared to negotiate and instead promised “direct action”, as this was “the only action which will bring immediate and certain results”.Footnote 39 Therefore, at 7 am on 17 March, European miners gathered around the shaft at Mufulira and voted by a show of hands to begin the strike. Tellingly, this occurred only two days after the union President, Tom Ross, had left the Copperbelt on leave and while the General Secretary Victor Welsford was out of the territory.Footnote 40

One of the main instigators at Mufulira was Frank Maybank, an underground timberman. Maybank had been born in Britain but emigrated as a young man and spent around fifteen years working as a miner in New Zealand and Australia. His experiences in the Australian labour movement and involvement in radical politics there – he had been a member of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) and a branch chair of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) – left a deep impression on him.Footnote 41 By the time he arrived on the Copperbelt in 1939 he had been involved in strikes in both Australia and New Zealand and spent time in the Soviet Union as a guest of the General Mineworkers’ Union.Footnote 42 “Ain’t I a bastard?”, he said years afterwards to settler politician Roy Welensky, “Well, I received my training in Aussie you know.”Footnote 43 Following the strikes he became General Secretary of the NRMWU union. Maybank himself does not seem to have had any personal animosity towards Africans or held particularly racist views, but at the same time he clearly identified his own constituency as skilled white workers and was largely uninterested in developments among the African workforce. In 1940 at least, he accepted that the NRMWU should be a whites-only union and supported militant action to secure an industrial colour bar.Footnote 44

Two days after the walkout at Mufulira, a similar meeting was called at Nkana mine. Around 700 people gathered to hear Brian Goodwin, a South African rock-breaker, reading through a long list of grievances and claiming that the management had refused to consider them at all. Following this, he announced: “Under an agreement which was made in our youth we first have to go to conciliation or to arbitration and it may be months and months before we get anywhere. I shall now close the meeting on behalf of the Mine Workers’ Union.” Whereupon, another miner leapt onto the table in front of Goodwin and asked: “Are we to take this lying down or are we going to take action?”Footnote 45 The meeeting voted to suspend the formal negotiating machinery and instead elected a committee of action, with Goodwin at its head, and adopted the demands of the Mufulira dispute. Urged on by strikers from Mufulira and former local Legislative Council member Catherine OldsFootnote 46 – who declared that miners should not be disuaded from striking by their wives or children – the meeting voted to deliver an even sharper ultimatuum to mine management: to agree to their demands within twelve hours or face strike action. Both the meetings at Nkana and Mufulira felt able to issue such blunt threats as they were not simply gatherings of union members but were effectively a mobilization of the European community in the mining towns protesting about the rising cost of living. At the Nkana mine, for instance, management informants estimated that around 200 women attended the meeting alongside male mineworkers, and they appear to have voted on the list of demands as well.Footnote 47

Figure 2 Frank Maybank, Northern Rhodesian Mine Workers’ Union General Secretary, c.1945.Personal papers of Frank Maybank, in author’s possession.

Daily-paid workers were caught in an ambiguous place in the mines. Strategically, they appeared to be in a strong position. As they were to demonstrate repeatedly in the 1940s and 1950s, the mines simply could not function without winding-engine drivers hauling people and ore up the shafts, rock-breakers opening new stopes, artisans repairing machinery, or power-plant operators keeping the lights on. The skills daily-paid mineworkers had and the jobs they did ensured they occupied a crucial position in the process of production. Yet, they also felt highly vulnerable.

Daily-paid men could be dismissed with twenty-four hours’ notice, at which point they would also lose their houses and have to travel hundreds of miles to find comparable industrial work, and they received no sick pay when they could not work due to illness. In addition to this dependency on the mining companies, daily-paid mineworkers also feared that they were liable to displacement from below by African workers. Similar to the white mineworkers on the South African Rand that Jeremy Krikler and Frederick Johnstone have analysed, daily-paid mineworkers appeared to be in a precarious structural position, with the presence of a much larger African workforce which could be employed on much lower wages weighing heavily on their minds.Footnote 48 Their fears were not completely unfounded: the introduction of a pension and bonus scheme for European workers in 1937 had resulted in a sharp increase in labour costs and, consequently, the mining companies were anxious to reduce costs by training Africans to do tasks previously undertaken by Europeans.Footnote 49

Partly because European labour costs were already rising, the head offices of RST and RAA in London had resolved to reject virtually all the demands.Footnote 50 Moreover, the managers on the Copperbelt would initially not even consider meeting representatives of the committees or the union.Footnote 51 Therefore, on 21 March, a large number of men from Mufulira joined mineworkers from Nkana and picketed all shafts and workshops on the property, shutting the mine.Footnote 52 The power of the informal action committees to make good their threats was now evident. At Mufulira, it appears that not a single member of the daily-paid workforce worked during the strike, while at Nkana the police reported that only two Europeans went underground to work on the first day of the strike.Footnote 53

Significantly, the strike now affected mines owned by both mining groups and the action committees were insistent that their grievances and demands covered the whole Copperbelt, not only the mines on strike. Meetings at Nchanga and Roan Antelope also backed the fairly extensive list of demands, which included action on wages, the closed shop, housing, a more favourable negotiating procedure, and silicosis.Footnote 54 The latter was passionately upheld by all white mineworkers in the region, silicosis prevention having already been raised by white mineworkers’ unions in South Africa in the 1900s and 1910s.Footnote 55 Demands effectively putting in place a colour bar by calling for the organization of work to be fixed along existing racial lines were added in the negotiations after the strike, and notably were supported by all prominent figures in the dispute including Maybank, Hodgson, and Goodwin.

Significantly, these demands were formulated with explicit reference to wages and working conditions in other mining and industrial centres in the British Empire and the United States – with particular praise reserved for Broken Hill in Australia – along with the perceived gains made in the Soviet Union.Footnote 56 Conditions in such disparate locations were relevant, as mineworkers on the Copperbelt saw themselves and the workers in these places as part of the same class and labour movement, a view that, to a certain extent, was reciprocated when the NRMWU started to rally the international labour movement in support of its demands. A flurry of telegrams to Labour MPs in Britain as well as to British and South African trade unions accompanied the 1940 strikes and subsequent disputes.Footnote 57 Through the British trade-union movement, the NRMWU built links with left-wingers in the Labour Party and the Independent Labour Party who then lobbied the British government in support of them.

Yet it was not only the white mineworkers whose thinking and demands were informed by their international links. The mine management, too, had been recruited from mining centres around the world. In particular, RST’s management structure had practically been imported wholesale from the United States, perhaps unsurprising as the company’s chairman Alfred Chester Beatty had enjoyed an extraordinarily successful career as a mining engineer in the US.Footnote 58 The General Manager of Roan Antelope, Frank Ayer, had been recruited directly from Phelps Dodge’s Morenci Mine in Arizona, while his subordinate at Mufulira, Peterson, was also an American mining engineer.Footnote 59 Copper companies had fought hard and successfully to keep trade unions out of the mines and smelters in the American West, including in Arizona, and Ayer’s experience there had taught him that unions were dangerous and always acted to undermine the authority of mine management.Footnote 60 The 1940 strike did little to modify this attitude, and following the dispute Ayer bluntly informed a local colonial official that “he was opposed to Unions anywhere”.Footnote 61

Ayer drew on his own experience of working conditions elsewhere in the world to contest the claims of the NRMWU. He rejected a claim that smelter conditions at Mufulira were so bad that they required a special allowance by getting men at Mufulira who had worked at smelters in Douglas (Arizona) and the Anaconda smelter in Butte (Montana) to vouch for the allegedly better conditions on the Copperbelt.Footnote 62 Other managers adopted a similar approach – disputing wage claims with reference to wages and working conditions on the Kent coalfields, for instance –Footnote 63 but Ayer found that his hard-line attitude had left him isolated. Ayer’s tactics had failed during the strike and other managers had to pressure him into negotiating. Only a few months after the strike, RST directors transferred Ayer from Roan Antelope, his removal having become a key demand of the union.Footnote 64

Notably, this demand and the general hostility towards American managers was itself informed by the NRMWU’s awareness of the international links of mine management, and its knowledge of developments in American mining regions. The union knew that “Mine Managements operating in Northern Rhodesia are largely influenced by American training and ideology”, and, in particular, believed that Ayer’s ideas for employee committees in the mines represented an existential threat as “the history of such concerns in the USA” showed that they were “capable of destroying completely the spirit and principles of the NRMWU”.Footnote 65

Ironically, given that this dispute helped cement racially exclusive working practices, the position of white workers was reinforced by the fact that their dispute precipitated a larger and more serious strike by African mineworkers. A day after white mineworkers returned to work on 27 March, African mineworkers came out on strike at Nkana Mine and then at Mufulira. This dispute culminated in a protest at Nkana where seventeen strikers were killed and around sixty-five injured after soldiers opened fire on the crowd when some strikers pelted them with stones.Footnote 66 Significantly, the strike was confined to the mines where white mineworkers had walked out, even though the low pay for African mineworkers and harsh conditions in which they worked were similar at all four mines. For its part, mine management was convinced that the white workforce had either inspired or directly orchestrated the African dispute.

There appears to have been some truth in this fear. Among individual white mineworkers it appears that some did take the initiative to encourage African mineworkers to strike, and since many white mineworkers supervised groups of African mineworkers they had ample opportunity to do so. At the Forster Commission, established to investigate the 1940 strikes, Changa Mwinangumbo, an underground miner at Nkana, claimed that white miners returning to work openly questioned why African miners had come to work after the strike, and said that they would get more money if they stayed away.Footnote 67 Yaphet Gerusi, a shaft clerk and member of the committee representing African strikers at Nkana, also claimed that European miners had advised them to strike.Footnote 68 Other African mineworkers pointed to the example of the successful European strike, rather than direct encouragement, as the trigger for the African dispute.Footnote 69 Regardless of the precise contribution white mineworkers may have made to this strike, it added to the pressure on mine management. Faced with the prospect of continuing industrial chaos, the mine management eventually caved in and agreed to most of the NRMWU’s demands. A new recognition agreement to this effect was signed in July 1940, although the demand for a closed shop was resisted until 1941.Footnote 70

This agreement did not satisfy either side. The companies considered that the agreement had been forced on them and remained unreconciled to it, particularly as their acquiescence had not bought industrial peace. Russell Parker, an American mining engineer and assistant to the chairman of RST, Chester Beatty, admitted frankly that he “sometimes felt that in face of this continuously increasing demand he would like to tell the Union to go to hell”.Footnote 71 The NRMWU, for their part, pressed their advantage, and the 1940 strikes were the first in a series of efforts by the union to wrest control over the functioning of the mines and the mining towns where management’s writ held sway. Disputes followed, in the course of which the union won partial control over the mine recreation clubs, as well as an increased say in the allocation of mine housing, and got copper production committees established, which involved shop stewards in the day-to-day running of the mines.Footnote 72 The NRMWU grew progressively more ambitious, and any grievance, they warned, had to be settled immediately, “for if they are allowed to go without settlement for the duration [of the war], they can only be settled by revolution”, of the kind that had occurred in Russia.Footnote 73

INDUSTRIAL UNREST IN KATANGA

The labour policies of UMHK in Belgian Congo offered white mineworkers on the Copperbelt – many of whom had previously worked in Katanga – a vision of the future if the mining companies were given a free rein. Two major strikes by white workers in Katanga after World War I had convinced UMHK of the importance of retaining tight control over their white workforce and replacing them with African workers. In April 1922, the UMHK board noted, “our officials in Africa are convinced of the necessity of employing native labour to the largest extent possible in substitution for white labour”.Footnote 74 The use of opencast mining – possible as there were rich ore deposits nearer the surface in Katanga – rather than underground mining facilitated this process, but UMHK also made a concerted effort to train African workers to replace Europeans in surface jobs and in their underground operations. By 1941, there were reportedly only 38 Europeans working underground at Prince Leopold Mine, located only a few hundred yards from the border with Northern Rhodesia, and around 1,100 Africans.Footnote 75 This allowed UMHK to reduce its total wage bill steadily in the interwar period.

The implementation of the colour bar on the Copperbelt in 1941 revealed that a similar but more gradual process was also underway there. It had not been possible to impose a uniform colour bar across all four mines because of what came to be known as “ragged edge” jobs. These twenty-seven jobs were tasks done by Europeans in some mines – and according to the colour bar could only be performed by Europeans in these mines – but were done by Africans in other mines, and included bricklaying, operating smaller winding engines, and driving locomotives.Footnote 76 “Ragged edge” jobs formed only part of the tasks undertaken by European mineworkers, and pointed to an ongoing process of job fragmentation: mine management did not think it was realistic, in most cases, to replace European mineworkers directly, and instead sought to break down European-held jobs into smaller tasks for which it would be easier to instruct African mineworkers. Fragmentation was possible as many of jobs performed by Europeans involved several discrete tasks that could be separated into smaller, less skilled jobs, such as artisans performing both routine and complex repairs on machinery. By 1939, Nkana Mine management had decided that Africans could perform certain tasks as well as Europeans, so more work should be done by them.Footnote 77 It is probably not a coincidence that one of the few cases of outright displacement subsequently took place at Nkana mine: in April 1941, three European screen operators in the mill (who worked the screen preventing larger rocks from entering the milling process) were replaced by three Africans, justified on the grounds that the mill was no longer operating at full production.Footnote 78 The ensuing furore and threats of further strike action finally compelled the mine management to accept a colour bar and closed shop in August 1941.Footnote 79

Wartime developments had generated great pressure towards a formal colour bar, partly because it brought the Katanga mines and their composition of labour “closer” to the Copperbelt, thus increasing anxiety among Europeans there. After the fall of Belgium in May 1940 the British Government began purchasing the entire copper output of the Katanga mines.Footnote 80 Representatives of the NRMWU explained to trade unions elsewhere in the world the obvious danger this represented to the Copperbelt:

As the British tax-payer was paying for all copper production in both territories it would not be long before somebody would want to know why our wages were much higher for the same work as they were in the Belgian Congo […]. Naturally the NRMWU were forced to take a very keen interest in the standards of the Congo.Footnote 81

In August 1941, white miners in Katanga appealed to the NRMWU for assistance in forming a union. UMHK’s predominately Belgian white workforce were contractually forbidden to join a union, so this was done in secret when several hundred men met clandestinely in the forest near the border to establish the Association des Agents de l’Union Minière et Filiales (AGUFI).Footnote 82 This was a development that UMHK would not tolerate, and following a strike in June 1942, the union’s leadership was arrested and imprisoned for “defeatist talk”.Footnote 83 This provoked further strikes in August and, in response, the union leadership was deported and spent the rest of the war in preventative detention, events which foreshadowed what was about to happen on the Copperbelt.Footnote 84

The NRMWU were already closely entangled in these events. Three miners from the Copperbelt were arrested by Belgian police at a nocturnal meeting in Lubumbashi on the eve of a strike in August – they implausibly claimed they were on holiday – and the union was considering launching sympathy strikes in support of Belgian miners.Footnote 85 On the Northern Rhodesian side of the border, the ground was being prepared with leaflets denouncing the Congo administration, drawn up by a Belgian miner at Nchanga Mine who had been deported from Belgian Congo, and distributed across the Copperbelt by the NRMWU.Footnote 86 The union was also reaching out internationally and, in the UK, the Communist MP Willie Gallacher responded to a telegram from the NRMWU by pressing the Colonial Secretary to remove any obstacles put in the way of the recognition of AGUFI.Footnote 87

Further strikes in Jadotville in September prompted an even more determined response from UMHK. From the beginning of the strike a “virtual state of siege was declared in Jadotville”, according to the British Consul in Elisabethville, with roads out of the town closed, public meetings forbidden, and a curfew imposed, all enforced by African soldiers and police.Footnote 88 This provoked desperate appeals for help across the border. Delegates from the Copperbelt had met representatives of the UMHK workforce in secret inside Katanga on 2 August and pledged unqualified support for AGUFI; now they began to attempt to fulfil this promise.

That this would mean disrupting wartime copper production did not faze some union members. NRMWU president Pat Murray acknowledged that copper production was important, but warned Clement Atlee: “We say, ‘that international trades’ unionism is of equal importance’.”Footnote 89 Telegrams were immediately despatched to other MPs in Britain, urging them to lobby for the release of the Katanga union’s leadership and, for good measure, that prevailing working conditions and wage rates on the Copperbelt be extended to Katanga.Footnote 90 At the same time, preparations began for industrial action on the Copperbelt, and Maybank telegraphed the Rhodesian Railway Workers’ Union (RRWU) to suggest joint action: “Congo strike in progress. Black troops used against white population. Evidence of no shooting yet. Feeling rising here request you wire Belgian Government insist on democratic rights of European workers, also indicate if necessary railway employees will refuse to handle Congo passengers and goods.”Footnote 91

The RRWU were unwilling to act, but the Northern Rhodesian Government took this as a blatant threat to disrupt the war effort. The Governor, Sir John Waddington, felt the situation was slipping out of his control, and with “extremists on both sides of the border […] in close contact”, he pleaded for troops to be deployed as there were fears the territory would see an armed uprising like the Rand Revolt.Footnote 92 The crucial importance of the Copperbelt to Britain’s war effort ensured that this threat was discussed on 16 September at the Chiefs of Staff Committee in London, where Winston Churchill ordered the army to deploy a battalion of white troops from the Middle East as quickly as possible.Footnote 93 A heavy presence of troops was necessary, the Colonial Secretary warned, as “[t]he temper of the workers on the Copper Belt is so inflammable that a strike might lead to widespread sabotage and the destruction of mining machinery”.Footnote 94

Despatching a battalion from the Middle East could take weeks and the government feared that they would lose the initiative if action was delayed. Instead, the Southern Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment, then stationed at Moshi in Tanganyika, was deployed. On 5 October, hundreds of troops from this regiment were moved under conditions of strictest secrecy to all the Copperbelt towns. A duplicate key to Maybank’s flat was obtained, allowing troops to arrest him there in the early morning. Luckily, he had left his pistol in his car the previous night.Footnote 95 Soldiers also quickly apprehended Chris Meyer, another prominent union member at Mufulira, and Jacobus Theunissen, who was not a union member but an Ossewa Brandwag activist, and removed them from the Copperbelt by plane.Footnote 96 These troops then remained on the Copperbelt for two weeks.Footnote 97

INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT

Taken by surprise, the NRMWU reacted furiously and immediately began preparing for industrial action on the Copperbelt, while at the same time utilizing the personal and political connections of their members to rally the labour movement internationally. Campaigns were soon underway in Britain, South Africa, and Australia. Meyer, who had been rapidly removed to South Africa, was well-connected among the trade-union movement there as he had previously worked on the Rand. He had been on SAMWU’s General Council and an active member of the South African Labour Party and was thus well placed to initiate a campaign against the deportations.Footnote 98 To assist him in this, the NRMWU despatched Jim Purvis to South Africa.

Purvis – a surface electrician at Roan Antelope who had been a founding member of the NRMWU – also had considerable experience in the trade-union movement and on the international circuits of white labour. Born in Australia, Purvis had been an active member of the AWU in Queensland, worked in a foundry in northern England, returned to Australia and then left again for South Africa after a stint in prison, and was in Johannesburg during the Rand Revolt before ending up on the Copperbelt in the late 1920s.Footnote 99 He too was well-known in the trade-union movement in South Africa. Purvis, however, had been deeply antagonistic towards other leading members of the union in the past – repeatedly expressing his hostility towards Maybank, Hodgson, Ross, and Murray to managers and government officials – though he closed ranks when Maybank and Meyer were arrested.Footnote 100 This antagonism would subsequently be effectively used by the Governor to derail the campaign.Footnote 101

Purvis, Meyer, Jack Hodgson (who had been declared a prohibited immigrant and refused re-entry into Northern Rhodesia in 1941), Erica Hodgson, and Sarah Zaremba, the NRMWU’s acting general secretary, formed a committee in Johannesburg to rally international support to return Maybank to the Copperbelt. The language used by this committee and the NRMWU more generally is significant and is worth examining. It was class-orientated and internationalist and reflected both the radical politics of those writing it and their awareness of what would appeal to international audiences. They avoided using overtly racist language, but also did not include expressions of support for the African workforce or any acknowledgement that African workers had any role to play in these disputes.

On the Copperbelt, the initial statement of the NRMWU, which appears to have been drawn up by the union’s President Murray, though also signed by the rest of the union’s General Council, denounced the “jingoism, misinterpretation, lies, propagated by a whispering campaign instigated by a quasi-fascist minority”, that had led to an “attack upon the working man’s organisation […] a deliberate attempt to smash that organisation and throw the workers into a state of chaos”. The General Council acknowledged, furthermore, that the main struggle was “between the great social democratic idea on the one hand and the powerful Nazi-fascist idea on the other”.Footnote 102 This statement was rapidly distributed to the union’s international supporters and communist and left-wing Labour MPs in the House of Commons were soon pressing the Colonial Secretary to release Maybank.Footnote 103 Statements issued by the Johannesburg committee were addressed to “the Trades Union and Labour Movements of the Democratic Countries and all Workers of the Allied Nations whos [sic] Interests are those of the Worker”, but made no mention of Africans other than denying the allegation that Maybank and Meyer had been organizing groups of African mineworkers.Footnote 104

Purvis was sent to tour South Africa and used similar language in the statement he delivered to white trade unions across the country. The NRMWU, he assured South African trade unions, was “doing everything in its power to bring about the defeat of Nazi Germany and Fascism”.Footnote 105 Purvis was able to secure support from a range of white trade unions – including the powerful SAMWU – and from the South African Trades and Labour Council (SATLC).Footnote 106 These unions sent joint delegations with the NRMWU to lobby the South African Government and crucially helped obtain the support of the British Trade Union Congress (TUC).Footnote 107 Consequently, the TUC sent delegations, including its General Secretary Walter Citrine, to the British Government demanding Maybank’s release and urged its local affiliates around the UK to join this campaign.Footnote 108 The breadth of this campaign and the extent of the NRMWU’s network of supporters are perhaps best indicated by the protest letter from Romford Trades Council, a local trade-union association near London, to the Colonial Office, which echoed the NRMWU’s wider demands virtually word for word.Footnote 109

The SALTC and the Johannesburg NRMWU committee also spread the campaign to Australia, as they called on the support of mineworkers’ unions there.Footnote 110 The Australian Coal and Shale Employees’ Federation took up the campaign and called on Prime Minister John Curtin and the Labour Government to help the union establish an “Australia-wide campaign to demand that the Rhodesian Government allow Maybank and Meyer to carry on their union activities”.Footnote 111 In Australia, as well as in Britain and South Africa, the trade-union movement saw a commonality of interest with the Copperbelt’s white mineworkers, and saw that the actions of the Northern Rhodesian Government threatened these interests.

These connections were bolstered by Maybank’s own radical political links. Independently of the SALTC, a friend of Maybank tipped off The Ironworker, the paper of Federated Ironworkers’ Association of Australia, that one of their readers had been detained in Northern Rhodesia for allegedly undermining the war effort. “The victim of this patently absurd charge is Frank Maybank”, explained The Ironworker, “a staunch anti-Fascist and first-rate trade unionist”, who was “well-known in W.A. [Western Australia] industrial circles”.Footnote 112 This statement was reprinted in the CPA newspaper Tribune, which added “[t]he Australian labor movement must utter a mass protest” against the detentions.Footnote 113 Protests from the Ironworkers’ Association calling for Maybank and Meyer’s immediate release soon followed, to governments in both Australia and South Africa.Footnote 114 Similarly, ties to Britain were strengthened through Maybank’s involvement in the communist movement. The Communist Party of South Africa’s newspaper The Guardian worked closely with the NRMWU committee in Johannesburg, and the publication was circulated on the Copperbelt by the NRMWU.Footnote 115The Guardian’s championing of the white mineworkers’ cause brought the support of British communists. “The Rhodesian copper miners are fighting”, reported the Communist Party of Great Britain, which urged its supporters to back them as they echoed the NRMWU’s demand for an inquiry into copper production.Footnote 116

Despite the support of Romford Trades Council, the campaign proved insufficient and Maybank was deported from Northern Rhodesia to the UK in late December 1942. The NRMWU was effectively competing with the international networks of the British Empire and, to a lesser extent, the mining companies and came off worst. The mining companies had been pressing the colonial administration and the British Government to take action since late 1940, and furnished them with incriminating evidence against Maybank from the Chamber of Mines in Western Australia, which was added to the case against him.Footnote 117 The networks of empire proved highly effective in combating and contradicting the information disseminated by the NRMWU and its allies, especially when provided with highly damaging allegations by the Northern Rhodesian Government. In Northern Rhodesia, the campaign had been seriously undermined when Governor Waddington revealed to the NRMWU leadership on 27 November that it was Purvis himself who had complained to the Governor in mid-1942 that “the position was extremely critical on the Copperbelt”, as Maybank was stirring up trouble over wages. Purvis had added, unsolicited, that Meyer was a leader of Ossewa Brandwag and “was the most dangerous man on the Copperbelt”, and the Governor claimed this is why he had to act.Footnote 118 Unsurprisingly, this provoked a huge internal row in the union, and the planned strike on the Copperbelt was cancelled.Footnote 119

This information was included in a short statement by the Governor and was used to successfully derail campaigns over the deportations wherever the NRMWU had managed to start them. The allegations followed Purvis to South Africa and were circulated among mining unions there, prompting several to repudiate their support for the NRMWU.Footnote 120 In Britain, the TUC quietly dropped the campaign after learning of Purvis’s role.Footnote 121 Bertie Brodrick, SAMWU’s general secretary, even visited the Copperbelt in late December 1942 to dampen the NRMWU campaign, and declared publicly there that the deportation was not an attempt to break the union.Footnote 122 Brodrick’s statement was despatched to Australia, and forwarded to the Miners’ Federation by the authorities.Footnote 123

In trying to prevent the deportation of Maybank and Meyer, the campaign was a failure. However, the NRMWU kept up the pressure and the subsequent demand – that Maybank be allowed to return to the Copperbelt – succeeded in catching the imagination of the British trade-union movement again. That this cause was related implicitly – via the fear of a Katanga-like composition of labour being introduced in the Copperbelt – to racial exclusivity passed without comment in the British labour movement. Almost as soon as Maybank arrived in the UK, he was presented first and foremost as a victimized trade unionist.

Maybank met Citrine in April 1943 and then appeared before the TUC General Council in June, where he convinced members that he had been deported as a result of his legitimate trade-union activities.Footnote 124 Maybank also won the support of the Mineworkers’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), under whose auspices he toured Britain’s coalfields to make his case. Ebby Edwards, the union’s General Secretary, reported that Maybank “had made an excellent impression on all the District Officers of the Miners’ Union”.Footnote 125 Abe Moffat, the communist mineworkers’ leader from Fife, raised the matter at the TUC annual congress in September 1943 and compared Maybank’s case to trade unionists exiled from Nazi-occupied Europe. The MFGB, Moffat announced, could vouch for Maybank’s integrity and he called on the whole British trade-union movement to back the demand that Maybank be allowed to return to Northern Rhodesia.Footnote 126

The major breakthrough in the campaign, however, came in February 1945 when Goodwin, by then NRMWU president, was elected as one of the twenty-two members of the Executive of the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) as the representative for Africa.Footnote 127 The deportations were still a live issue on the Copperbelt, and Goodwin pledged to raise the matter at the WFTU before leaving.Footnote 128 Goodwin was as good as his word, and pursued the matter with the TUC, MFGB Executive, and the WFTU. He also secured a visitor’s ticket to get Maybank into the conference, where Maybank raised the matter himself among delegates and got himself elected to the WFTU General Council.Footnote 129

Goodwin had won the NRMWU a potentially powerful position in the global trade-union movement at the same time as the war was drawing to a close. The urgent need for copper was dissipating at the same time as trade-union pressure was increasing. With these new developments, it did not take long for the British Government to give in, and in March 1945 Goodwin and Citrine finally secured what they perceived as justice for Maybank. The British Government reluctantly allowed him to return to Northern Rhodesia following the end of hostilities in Europe. Anticipating that support for this demand would only grow, it was thought best to announce the decision quickly to “avoid appearing to have given way to pressure”.Footnote 130 To the undisguised dismay of the mining companies, Maybank was unanimously reinstated as NRMWU General Secretary in August 1945. He rapidly resumed his previous role, vowing to shut down the entire Copperbelt following a strike at Mufulira Mine and, for good measure, turning up late at night at the house of the magistrate who had him deported to threaten him in person.Footnote 131

CONCLUSION

The struggles of the white mineworkers on the Copperbelt during this period reveal how they saw themselves and their interests: as a transnational, mobile workforce where conditions of work and wage levels had to be maintained and improved in multiple locations. In many ways, what was happening in mining regions in Britain, South Africa, Australia, and the United States was of more relevance than developments in Northern Rhodesia, and this international context is crucial to understanding events on the wartime Copperbelt. The mineworkers’ perception of their place in the labour movement was reciprocated and white mineworkers were able to mobilize support from trade unions in South Africa, Britain, Australia, and eventually the Soviet-dominated WFTU. For trade unionists in these countries, the world of European labour on the Copperbelt was similar enough for white mineworkers there to be recognized as comrades. For white mineworkers, relevant and natural allies were to be sought internationally among the trade unions formed by the British labour diaspora across the world, not locally.

This did begin to change during the 1940s. In the March 1940 strikes, it appeared that white mineworkers still held to what Keith Breckenridge referred to as “the key rule of white labour disputes” in South Africa in the 1920s: African workers were to be kept out of disputes between white workers and their employers.Footnote 132 Although their strikes in 1940 threw thousands of African miners out of work and helped provoke serious African labour unrest, there was no acknowledgement that the dispute concerned them at all. By 1943, though, NRMWU branches began to explore the possibility of organizing African workers, although few practical steps were taken until after the war.Footnote 133 In some ways this represents a move away from the politics of white labourism, but in another sense it does not. Rather than exclude non-whites, as white labourists had attempted to do elsewhere, African workers were to be incorporated as junior branches in a trade-union structure which would remain controlled by Europeans.

There was no real challenge to the substance of the politics of white labourism on the Copperbelt during this period as it was generally acknowledged among the white workforce that industrial militancy and racial exclusivity indisputably got results. They enabled white mineworkers to win some of the most favourable working conditions and highest wages on the planet by the 1950s. While not overtly racist or even particularly hostile to the much larger African workforce, radicals among the white workforce did not see African workers as their constituency. They can thus be described as passive white labourists who tacitly took the established order of things for granted or pushed, without resorting overtly to a racist ideology, to maintain the status quo. This is why Maybank could declare, without any note of contradiction: “[A]t Mufulira we took the stand that notwithstanding religion, race or politics, we are solid as workers.”Footnote 134

Wildcat strikes in support of their radical demands – which by logical consequence were racially exclusionary – were for white workers “the only action which will bring immediate and certain results”, and the success of these tactics proved an instructive experience.Footnote 135 Further major strikes hit all four mines in 1944 and in 1946, winning further concessions, and this informed a postwar strategy of intransigence in negotiations with the mining companies. Effectively, the victory won by white mineworkers in March 1940 helped alter the pattern of industrial relations in the mines for the subsequent two decades. Relatively few mineworkers broke with the politics of white labourism, and none did so more dramatically than Jack Hodgson, who went on to engage in armed struggle against the apartheid regime in South Africa.Footnote 136 His example is all the more dramatic because it was virtually unique; the vast majority of his former workmates were comfortable with their position in the world of European labour or at least accepted the racialized segregation of labour it implied.

This world would soon be disrupted in the postwar years by the emergence of a powerful African mineworkers’ union. African miners were soon making demands that the NRMWU could not ignore and would contest the place of the NRMWU in the international labour movement. The combination of industrial militancy and racial exclusivity, both of which white mineworkers saw as necessary to protect their interests, would become increasingly out of place in the postwar world. Yet the position of strength won by the NRMWU through its wartime struggles and its continued willingness to defend this position effectively insulated the white workforce from these wider changes until the late 1960s.