Introduction

For many us who have studied, researched, written, and taught about the influenza pandemic of 1918–19, the current period of the global viral pandemic is eerily and unpleasantly familiar. Today, the rapid global spread of a virus has prompted policies calling for widespread closures, social distancing, constant handwashing, and public mask wearing in additional to other non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). We have also seen pushback and resistance to these directives as well as substantial mismanagement of resources and a flood of misinformation. Much health policy has been inconsistently set at the local rather than federal level. These responses to our current pandemic closely mirror those to the pandemic 102 years ago.

That earlier pandemic infected 20–30 percent of the world's population, accounting for as many as 50 million deaths (estimates range from nearly 18 million to over 100 million), including roughly 675,000 Americans. In the United States, induction camps, cramped quarters, wartime transport, and industry generated optimal conditions the flu's transmission. Around the world, global interconnection had reached an apex in world history such that the flu was able to reach much of the world in a scant four months and to circumnavigate the globe within a year. The pandemic's three waves swept the United States from spring 1918 through winter into spring 1919, with the most fatalities occurring during the second wave in fall 1918. The flu undermined the war effort and the economy. It strained hospitals to and beyond their breaking points. It disproportionately infected and killed young people between 18 and 45 years of age. The virus most severely struck marginalized groups—including African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Indigenous peoples—and those of lower socioeconomic status.

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread aggressively this spring, the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era assembled this roundtable, bringing together scholars from a range of disciplinary background to talk about how we can think about and teach the history of the 1918–19 pandemic in this current age of COVID-19. Our hope was for the conversation to be wide ranging, but as appropriate for the journal, to also consider the ways in which the study of the early twentieth century continues to inform our understanding of pandemics and public health, science and medicine, politics, foreign relations, literature, inequality, race and racism, and social relations.

We came together rapidly because we have a sense that a great number of those who work in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era—in history, for sure, but also in range of fields, including not just colleges but also at the K–12 level—will be teaching the flu pandemic now, in the coming academic year, and in the years to come. We also are aware that our colleagues in history, political science, literary studies, American Studies, and beyond, are keen to have more content and to grapple with a number of ideas, insights, and advice regarding the influenza pandemic so that they can then use them in the classroom and to inform their work across fields and forums.

What follows is an edited and annotated version of a conversation that took place over email in June 2020.

Part I: Main Themes and Concepts

Christopher McKnight Nichols (CMN): As someone who has spent a great deal of time researching and teaching on the influenza pandemic of 1918–19, Nancy, I wanted to start with you. What themes do you find are most useful in making sense of this complicated history? Has the current novel coronavirus global pandemic of 2020 changed how you conceive of the flu pandemic and some of the themes you emphasize in your research, teaching, and commentary?

Nancy Bristow (NB): I will admit to feeling deeply humbled as I experience the Covid-19 crisis. I recognize now how little I understood about the overwhelming power of the uncertainty that comes with a pandemic born of a novel virus. I begin here to suggest how difficult it is to imagine the worlds of the past. Though it is one of the cautions I always offer my students—that the people of the past don't know how their story is going to turn out—I have gained a new and more visceral understanding of this element of the story of 1918 that I did not have before. The danger this new sense of empathy holds for me, and I think for all of us who teach about the 1918–1919 crisis, is that we need to continually remember not to read our own experiences onto theirs.

I have long conceptualized the pandemic of 1918–1919 as a window into the United States of that particular historical moment, a crisis that laid bare the values, norms, assumptions, and practices of its people in all their diversity and complexity. As a result, there are countless avenues of inquiry we might explore, a plethora of themes we might highlight. I'll begin with a few themes that I tend to emphasize, knowing others will expand and deepen my thinking.

Americans’ shock at the pandemic's power: By 1918 influenza was a familiar illness in a country increasingly certain, as a result of the bacteriological revolution and advances in medicine and public health, of its own capacity to prevent infectious disease. These dynamics enhanced the shock of the pandemic for the public, health care providers, and public health experts alike.

The suffering of the victims: The reality that this was a terrible disease to have or to witness sits at the center of this historical event. It is easy to get caught up in the numbers—25 million Americans sickened, 675,000 dead—but we have to push ourselves and our students to remember that the trauma that the illness and death carried was happening to real people, with family and friends, hopes and plans, passions and problems.

The smorgasbord of public health responses: Because the United States Public Health Service had no policy-making power, it was state, county, and city governments that determined the responses to the pandemic. Given the variety of levels of power and expertise held by public health officials around the country, a significant diversity of approaches resulted, translating into substantial differences in morbidity and mortality rates. It is worth noting, too, that the options available in 1918 for controlling the influenza pandemic were essentially the same as those we use today.

The powerful role of social identity: There was no singular experience of the pandemic. Gender norms, class status, racial hierarchy—all of these had a profound impact on Americans’ experience of the pandemic, and no exploration of the crisis is complete without an acknowledgment of this reality. Essential to this, too, is a recognition of the profound costs this held for so many people who lacked social, economic, and political power, in particular the poor and people of color.

The divergent experiences of the caregivers: In an era of strict gender norms, medicine and nursing were still deeply gendered professions. The meaning of this for those providing health care were profound. While doctors were unable to fulfill the masculine charge of controlling the disease, nurses proved successful in providing care, and as a result left the pandemic with a heightened confidence and enhanced public status.

The desire to make sense of the pandemic and the power of martial rhetoric: Americans found a range of ways to make the pandemic something meaningful rather than a wasteful catastrophe. Some saw the pandemic as part of God's plan, while others found democratic meaning in the crisis. Most common was the imagining of the pandemic as a war, a place to serve and where death could be bound up in a national cause. The use of martial rhetoric was largely rhetorical, and yet the pandemic and World War One were clearly intertwined in the American imagination.

Post-pandemic amnesia: Public life in the United States had little place for the pandemic in its aftermath. No monuments were built. No commemorations took place. Few memoirs or novels were written. It is not coincidental that only the blues seemed a suitable genre for its history. Was the pandemic just the wrong story for its time, the war a better fit for Americans’ sense of themselves?

The failure of Americans to respond to the lessons the pandemic might have taught: One of the aspects of the pandemic I find most fascinating is how little the nation changed as a result. There was no strengthening of the USPHS, no effort to build a health care system that could serve all Americans, no creation of a social safety net, and certainly no rejection of the system of white supremacy. The post-pandemic assertion of the status quo is striking.

Private trauma and remembering: The essential story of the pandemic was one of suffering. In the aftermath, that trauma was not forgotten, even if the public sphere had no place for those memories. What did that mean for those who had suffered in the decades to come?

Joseph M. Gabriel (JG): I've had a similar experience as Nancy in terms of gaining a new appreciation of the power of uncertainty that accompanies epidemics. I came of age in the late 1980s and the AIDS crisis was on my radar, but at the point in my life I wasn't directly connected to anyone who got sick or died from it. So my experience of that crisis has been very different than a lot of people's. I have also been incredibly fortunate so far in terms of my family's ability to weather this pandemic relatively unscathed. But I still feel the uncertainty in a visceral way that is new for me, at least in terms of the experience of epidemic diseases.

I think the themes that have already been laid out are really helpful. I'll just mention a few more that animate how I think about the 1918 pandemic and the history of disease more generally.

Disease categories change over time: Historians of medicine spend a lot of time thinking about how the definition, experience, and material reality of disease changes over time. A lot of this, though obviously not all of it, has to do with changes in medical thought. One of the key stories in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century medical history is the emergence of disease as discrete clinical entities that can be identified and studied, tracked, and counted. Before that disease was understood as resulting from the imbalance in the bodily system, with imbalance caused by lots of different factors like weather or strong emotions. So there wasn't a sense of distinct, discrete diseases in the same way that there is today. By the early twentieth century, however, diseases like “influenza” had been conceptualized as discrete entities with their own ontological status. So even though the virus hadn't been isolated yet, influenza had already become a “thing” that could be studied and its cause potentially identified. But medical science is always incredibly messy. The study of any disease is always deeply mixed up with politics, economics, and other aspects of life that we like to assume are separate from it.

Gap between scientific expertise/authority and everyday experience: The transformation of disease into a set of discrete entities was deeply intertwined with the development of scientific expertise and authority during the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries and led to a growing distance between the claims made by physicians and public health experts and the experiences and knowledge of many people. Increasingly the explanatory frameworks offered by experts made less intuitive sense to large sections of the public. Of course, there were always very large differences in cosmologies and knowledge-making practices between physicians and many groups of people, most notably indigenous communities and enslaved peoples. But by the early twentieth century, the development of scientific expertise in something that approaches a familiar form meant that physicians’ expert claims were increasingly alien to many people, even the social and economic elite. This separation of medical professionals from the general public coincided with the development of a whole host of laws and other ways of enforcing developing medical authority. People did not always go along with this developing authority, not because they were acting irrationally but because they were acting in ways that made sense within the contexts of their own lives, experiences, and knowledge-making practices. As a result, public health responses in 1918 were not just efforts to change public behavior. They were also efforts to promote and enforce explanatory frameworks for incredibly complex processes that sometimes contradicted the lived experiences and knowledge-making practices of nonexperts. This helps us understand resistance to public health measures in ways that moves us past the “irrational” framework for things like antivaccinationism and popular resistance to mask wearing.

Interaction between biology, environment, society, and behavior: For me, one of the fascinating things about medical history is that it really forces us to confront basic question about the analytic choices that we make as historians. In medical history, you can't ever escape the role of ideas, but you also can't escape the materiality of the past. So, the way that the pandemic played out was very much about the wide variety of public health responses that Nancy points to. But it was also about the way that biological mechanisms that operate at the level of people's bodies—the actions of viruses, immune response, etc.—interact with and are shaped by the social and physical environment on the one hand and on individual and group behaviors on the other. The 1918 pandemic had an unusual age distribution pattern, for example, possibly because of exposure among older people to an earlier influenza strain. I think it is really helpful to keep the interaction between viruses, human bodies, environments, and even ideas in mind when discussing the 1918 pandemic. Influenza A viruses and coronaviruses are not the same thing, for example, and this difference matters if we want to think about the experience of suffering, the distribution patterns of the diseases, and the role of developed immunity in the two pandemics.

Similarity and difference as analytic lens: Nancy made the point that we need to be careful not to read our own experiences of uncertainty today back into the past. It's a really important point. At the same time though, one of the strengths of historical analysis is that it helps us to understand similarities, both between the past and the present, and laterally, as it were, within time periods. I find this tension between similarity and difference really productive analytically. There are important patterns and commonalities that can and should be analyzed. Of course, we should be careful about assuming that different groups of people shared the same experiences just because they went through the same pandemic, whether the 1918 pandemic or today's. The two pandemics impacted disparate groups differently, especially along lines of race, class, and other dynamics. Keeping in mind these unequal experiences is really important because they can easily get lost or flattened out through narratives of national unity, or scientific progress, or even analytic choices that prioritize the high virulence of the virus during the second wave of the 1918 pandemic. Different people and different groups of people don't experience epidemics in the same way, now or then.

The centrality of suffering and our obligations to the past: Nancy already mentioned this, but I just want to emphasize and underscore it. Suffering was indeed the essential story of the 1918 pandemic, even as the manner and the degree to which people and communities suffered varied tremendously. There's a lot of ways to tell the story of the 1918 pandemic, and I think some are better than others. I might even go so far as to say that there is an ethics to the types of choices that we make here. These were real people with real lives, and I think we have a responsibility to treat their stories in certain kinds of ways that makes this clear. I feel like my colleagues in the field of medical history sometimes forget this. So, for me, it is really important to keep this in mind and to think seriously about the suffering of the people we write about—or their lack of suffering—and its relationship to the stories that we tell. There's an important issue here about utility as well—do we treat the past, and the stories that we fill it with, as a resource to create our own futures? I spend a lot of time criticizing physicians and research scientists for using vulnerable people to advance their own professional agendas. Sometimes I feel like historians do a similar sort of thing when we enroll people who came before us into our own narratives. When I think about it in this sort of way, the idea of a “usable past” is not quite as appealing to me as I typically assume (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Library of Congress: “St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps on duty in October 1918 influenza epidemic.”

CMN: These themes and approaches give us a lot to work with. Given the wartime and international dimensions of the pandemic in 1918–1919, Ben, I hope that you might also explore some of the broader context you see as essential to conceptualizing this topic?

Benjamin C. Montoya (BM): As a way to complement the comments from Nancy and Joe, I will pivot us to consider how the pandemic affected people outside the United States. This will give us a sense of how this influenza was truly a pandemic. Specifically, my comments will build upon Joe's suggestion that we should appreciate how different groups and peoples experienced the disease, as well as spin off a theme Nancy raised for consideration: how war shaped the pandemic experience.

The influenza came to the United States in 1918 during the last months of World War I. The domestic problems caused by the pandemic were soon augmented by a Red Scare, a wave of race riots, and labor strikes in 1919. Yet the pandemic arrived in Mexico at an even more troubling time for that nation.

The Mexican Revolution was in its eighth year when the influenza came to Mexico in the last months of 1918. Years of warfare had devastated many parts of the nation, terrorizing, killing, and displacing hundreds of thousands of Mexicans. A notable example of this destruction was in the state of Morelos, the home state of the Zapatista movement in south-central Mexico. Constant fighting between Zapatistas, led by Emiliano Zapata, and the central government in Mexico City, led by Venustiano Carranza, had undermined the local economy; poverty, hunger, hunger, and disease were rife. By 1917–1918, many villages in Morelos were empty, fields stood bare, livestock was nowhere to be seen. One American observer at the time compared the state of Morelos to the blood-soaked fields of Flanders in war-torn northern France of the same years. Many civilians migrated away to escape these various deprivations … and this was before the “final scourge” of the influenza came.Footnote 1

In contrast to the United States, Mexico was a nation in revolution when the pandemic hit. As such, many states, regions, and local communities were ill-equipped to handle the spread of a pandemic. The epic battles that had characterized the first half of the revolution (1911–15) had been replaced by a dizzying myriad of low-level, regional conflicts that, at times, tied into larger national struggles but were attributable also to long-standing, local, apolitical grievances. The years 1915 to 1920 were marked by high levels of crime, both rural and urban. Such crime paralleled the deprivations of the revolution: violence, destruction of property, displacement.Footnote 2

Under such conditions, it should come as no surprise that infectious diseases were already prevalent before the outbreak of influenza. Typhus, that “classic disease of wars and deaths,” spread throughout Mexico in 1916–17. It had been cropping up among the various revolutionary factions in 1914 and 1915, but during the winter of 1916–17, it hit civilian centers such as Mexico City. At its peak there, typhus claimed 1,000 victims a week. Normal conditions (20 deaths per week) did not return until 1918. Typhus was equally deadly in surrounding towns and provinces. Guanajuato and Zacatecas were the states hit worst: at its height in the summer of 1916, typhus claimed the lives of 200 people a day in Zacatecas.Footnote 3

Typhus was the main killer in 1916–17, but there were other diseases that affected Mexican society amidst revolution. Smallpox—revived during the revolution's early years—first appeared in Morelos (1912), from where it then made its way to Mexico City, and spread throughout other parts of the country such as the state of Chihuahua in the north and the state of Veracruz in the east. In Veracruz as well as eastern and southern regions such as Chiapas and Yucatan, smallpox “conspired” with endemic malaria and yellow fever to kill many in regions throughout eastern and southern Mexico, such as Chiapas and Yucatan.Footnote 4

It was not just the deprivation and destruction of war that allowed such diseases to run rampant across the Mexican landscape. The mobility revolutionary armies and displacement of civilians played a large role in perpetuating these outbreaks. Zapatistas from Morelos brought malaria to Mexico City when they occupied the capital city in December 1914. Francisco “Pancho” Villa's partisans suffered from and spread typhus as they descended from the Mexican north to famed battlegrounds in central Mexico, notably to the state of Zacatecas.Footnote 5

Ultimately, it was the movement of displaced persons, most of whom were landless laborers (peons), that carried various diseases to many parts of Mexico and even into the American southwest, as many fugitives sought escape from Mexican travails by entering the United States. The revolution led to a fundamental redistribution of Mexico's population. Soldiers, deserters, bandits, beggars, and migrant workers, fugitive peons, they all sought refuge in the United States for various reasons. It is difficult for immigration historians to delineate who fled northward. Immigration historians are equally uncertain about how many Mexicans entered the United States during these years. Some scholars estimate that it was as many as 1.5 million people. If it is difficult to know which and how many Mexicans migrated northward during the 1910s, it is much easier for scholars to understand why they did so: to escape revolution and poverty.Footnote 6

It is within this context of violent revolution and chronic disease that the influenza entered Mexico in late 1918 where, as in Europe, it encountered a war-weary and hungry population. Unlike other diseases like typhus, influenza came and went rapidly: it swept through northern states such as Chihuahua in a matter of weeks. But its incidence and mortality were greater than past diseases. And war-ravaged regions of Mexico such as Morelos were “perfect grounds” for the pandemic, as citizens suffered from fatigue, starvation, bad water, and continual moving. Mortality rates were high, much higher than in healthier industrial societies that had also experienced years of war. In England, for example, where a great proportion of the population contracted influenza, the total mortality was about 4 per 1,000. By contrast, one estimate of Mexican mortality was as high as 20 per 1,000. While hard data is lacking to confirm this estimate, anecdotal, contemporary evidence confirms that the 20:1,000 rate was credible even if not totally accurate. The Mexican north bore the brunt of the influenza outbreak. Some towns in Coahuila and Durango saw hundreds of deaths in a matter of days. Mortality rates were much lower further to the south: 8 per 1,000 in Veracruz, for example. All told, if we assume that the 20:1,000 estimate is close to accurate, around 300,000 Mexicans died of influenza during the winter of 1918–19.Footnote 7

Yet it is easy to get caught up in mortality numbers, as Dr. Bristow's comments before remind us (see her point on The suffering of the victims). For as important as mortality rates are for the pandemic of 1918–19, we should also note the velocity of death caused by influenza. Mexico's medical and sanitation services could not cope; there were insufficient doctors, medicines, hospital beds, and burial places. In Zacatecas, corpses were piled up unburied; in Ciudad Juárez, the sick were billeted outside the town on the racetrack; in Mexico City, the authorities closed public buildings and mass was held in the open air.Footnote 8

At the center of it all, Morelos, whole villages and towns were abandoned. Zapatistas, already weakened by years of war and malnutrition, died by the thousands in December 1918. “For war-weary Mexico, as for war-weary Europe,” historian Alan Knight states, “the winter of 1918/19 was a bitter time[.]”Footnote 9

CMN: As I did with Ben, Elizabeth, I wanted to turn to you now because I hoped you might focus your reply on main themes for conceptualizing the pandemic of 1918–19 in light of COVID-19 as well as your work on modernism and in literary studies?

Elizabeth Outka (EO): I'm delighted to be in conversation with you all.

I study the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic primarily through the lens of literature. This mode of representation offers a particular kind of history—one of senses and emotions, one that explores how bodies and minds interact with each other and the world. Having immersed myself in this art for many years, when COVID struck I found the experience uncanny in its familiarity (hard to say if this sense of déjà vu is better or worse than the surprise Nancy and Joseph describe …). Much of the pandemic literature I examine plunges the reader into the uncertainty that gripped both individuals and cultures at the time; when that uncertainty arrived in the COVID outbreak, I found the art offered a map for navigating this new landscape.

As Nancy, Joe, and Ben observe, the influenza pandemic was experienced differently depending on personal identity (race, class, gender, and more), location, previous health history, inequalities in health care systems, politics, and many other factors. In literature, these factors helped determine where and when and how art about the pandemic was produced, and who was able (and willing) to do that producing. In countries heavily involved in the First World War, for example, writing about the pandemic could seem disloyal, a distraction from the ‘real’ story of the war, even though the pandemic globally killed far more people. In works by writers like Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, and W. B. Yeats, who all had encounters with the virus but who lived in countries that had been fighting the war for four long years, the pandemic is present but covert. The American writers Katherine Anne Porter, Willa Cather, William Maxwell, and Thomas Wolfe wrote about the pandemic more directly, perhaps because the United States joined the war later (though plenty of American writers avoid the pandemic entirely). Countries only minimally involved in the war often had different aesthetic responses; in Nigeria, for instance, which suffered heavy losses in the pandemic, the experience, as Elizabeth Isichei and Jane Fisher observe, entered into oral traditions and survived in “popular memory more coherently” than in the countries more involved in the war; such experiences were later chronicled by novelists like Elechi Amadi and Buchi Emecheta.Footnote 10

Alongside the differences in pandemic experiences and the art it produced, some broad themes appear in the interwar literature I studied, though even these themes resonate in varying ways.

Temporal disruption: The sense of time being disrupted, split, and flowing unevenly weaves through much of the literature. Writers and artists capture the unsettled time of delirium, the elongated days of recovery, the recurrence of past times in flashbacks, the speed at which the virus overtook the body, and the way a life-altering experience may split time into a before and after. The pulsing, present tense immediacy of a poem like Yeats's “The Second Coming,” for example, captures the temporal dislocation of the flu's fever, as Yeats had witnessed his wife experiencing in the weeks before he completes the poem.

Contagion guilt: In war, people kill others deliberately, though the guilt can be terrible. In a pandemic, people typically kill by accident, as a disease passes from person to person, and often between loved ones. The literature and art are marked by this haunting truth, by the fear that without ever meaning to, one might bring death to others. The author William Maxwell, in his novel They Came Like Swallows, speaks of the agony of such fear, when a simple, loving interaction may have unwittingly transferred the virus.

The invisibility of the enemy: Interwar modernist literature, with its indirection, its uncertainty, and its often-amorphous plots, was particularly adept at capturing how, in 1918, the enemy became invisible. Writers like Porter, Eliot, Woolf, and Yeats sketch the climate of anxiety this invisibility produced, the sense of a vast, unseen threat that was both everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

The dangers of scapegoating: The very invisibility of the enemy could lead to dangerous forms of victim blaming and scapegoating. Some in the United States, for example, feared the virus was a German plot, a fear satirized by Porter in “Pale Horse, Pale Rider.” The horror writer H. P. Lovecraft problematically embraced the scapegoating, using disease metaphors saturated in pandemic imagery to uphold his racist beliefs that Aryan bloodlines were being polluted by immigrant hordes.

The suffering body: As Nancy, Joe, and Ben point out, statistics may hide the intense suffering that individuals experienced in the pandemic, and the often-varying levels of intensity. The literature works to capture individual bodily suffering both during the virus's acute stages and during its brutal lingering aftermath (if survived at all). Porter's “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” offers a searing account of the physical pain of this virus that to her character seems almost beyond representation, from the burning fevers to the nightmarish delirium. Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway evokes the continued damage the virus could do to a body, like the lingering enervation that could make climbing a short flight of stairs exhausting.

Disrupted mourning: As others have described, the influenza pandemic profoundly disrupted mourning rituals in many areas. Coffins ran out, bodies were piled in stacks and then buried in mass graves, and fears of contagion prevented people from gathering for funerals or to mourn together. Insecure burials, a sense of perpetual mourning, and the unquiet dead weave their way through the literature, from the corpse insecurely buried in the back garden in Eliot's The Waste Land to Lovecraft's proto-zombies in his story “Herbert West: Reanimator,” to the elegiac, ghostly wind that blows through Thomas Woolf's Look Homeward, Angel.

The Vertigo of Loss: The sheer number of deaths in the pandemic may be displayed in numbers, in graphs, on maps, and in histories. The literature records grief on individual levels that may nevertheless resonate widely, capturing small losses as well as bigger ones—the particular gestures or scent of a parent, the expressions of a brother, the sound of a friend's voice, all gone alongside the vast losses of the persons themselves, the destruction of families, and the breakdown of communities. The peculiar vertigo that loss may bring, defined as it is by absence and emptiness, often grants no place to stand. The literature both captures such experiences and grant some degree of footing.

E. Thomas Ewing (TE): My understanding of the 1918 influenza epidemic came relatively recently in terms of my academic career, in ways that I think are broadly suggestive of how historians and the public have thought about this remarkable moment in world and American history. I had taught twentieth-century world and European history many times without ever mentioning influenza. The omission of this topic, in hindsight, had three causes, which were, I suspect, broadly true for other scholars. First, the years 1914–1921, it seemed had too many other important events to cover (the First World War, the Russian Revolution, the postwar settlement, women's suffrage, and the rise of anti-colonial movements across Asia and Africa). Second, I was ignorant about the scope and scale of the epidemic, which had never been taught to me and did not appear in the textbooks and scholarly works I was using to prepare to teach. And third, I had a vague sense that while the epidemic was costly, it didn't change anything, in contrast to the decisive turning points such as the end of world war, the first communist government, and the rise of nationalist movements for independence. It is only in the last decade, once I became involved in researching and then teaching about this influenza, that I realized each of those premises is faulty, as the epidemic did mark an important development in scientific knowledge, in the structure of communities, and in the relationship with the natural environment. This roundtable, as well as the dramatic increase in scholarly and popular works on this history, reflects significant changes in how the profession conceptualizes the historical significance of influenza.

I appreciate the discussion of the influenza in Mexico by Ben because so much research on this epidemic remains centered in Western Europe, the United States, and English-speaking regions of the world. This bias results to a certain extent from the geographical location of scholars, but even more is the result of the Eurocentric nature of medical research, statistical compilations, and case reporting in the early twentieth century. This bias exists even within countries. In United States history, for example, the histories of certain cities, such as Philadelphia, New York, St. Louis, Chicago, San Francisco, and Seattle, are circulated far more widely and repetitively than cities in the southeast, the mountain west, and especially the states along the border with Mexico. Scholarship in the last two decades examining the 1918–19 influenza in Asia, Africa, and Latin America has added a great deal of knowledge about this epidemic, including local variations; evidence of greater impact; and, as in the case of Mexico cited above, the importance of understanding how influenza exacerbated the impact of other diseases, problems in the health infrastructure, and structures of inequity. For historians of epidemic, the challenge is integrating these country and regional case studies into a synthetic history of the global pandemic that recognizes differences while also building a narrative of the whole world.

One important shift in historical conceptualization of the epidemic has been the continued exploration of the “origins” of the disease. The popular story of the influenza “beginning” in one county in Kansas in early 1918 has been dispelled by the accumulating evidence of widespread cases of acute and even deadly influenza in Europe and elsewhere in the United States already in 1916 and 1917. This evidence is consistent with contemporary scientific understanding of how the influenza virus mutates, yet also reveals the key virologic question about the 1918 epidemic: Why did a particular mutation became so deadly so quickly in so many regions? The question matters now and in the future, of course, in predicting future mutations. This global approach to understanding the 1918 epidemic is especially important in teaching students and communicating to the public, where the desire for a compelling story often leads to an exaggerated focus on a single country doctor in a rural community in the Midwest.

As a global historian, I am especially interested in recent research that connects the ways that European powers conscripted labor from Asia to build fortifications on the front lines—and how these laborers might have contributed to the global transmission of the disease. Research by Mark Humphries has traced reports of widespread influenza and other diseases among Chinese laborers recruited by British agents, transported across Canada, and then shipped to Europe. In addition, historians of the epidemic elsewhere in the world have also traced how the return of laborers and soldiers after the war may have contributed to later waves of the epidemic. This narrative appeals to me because it further illustrates how the Great War in Europe was, in fact, an extension of the imperial system in an especially exploitative manner, as laborers from colonized regions were forced to work on behalf of their imperial governments in Europe as well as in the colonized regions themselves.

Finally, I agree very much with the other contributors that suffering is the key experience of this epidemic, and that historians have a responsibility to understand the experience of this epidemic from the perspective of the victims, their family members, and the caretakers who directly encountered the disease in this way. It is also important, however, to recognize that survival was also part of the experience of the epidemic. The 675,000 deaths in the United States represented less than 0.6 percent of the total population, meaning that the overwhelming majority of the population survived. In addition, the majority of those who fell ill with influenza also survived. The case fatality rate was estimated at between 2 and 5 percent, meaning that approximately 95 percent of those who fell ill with the disease did not die from this case. The case fatality rate was probably even lower, because only cases actually reported by physicians to the health department were actually counted. In rural regions, the death tolls from this disease were often quite low. In rural southwest Virginia, deaths from influenza in 1918 represented even smaller percentages of the total population: 11 deaths from a population of 5,000 in Craig County; 24 deaths from a population of 14,000 in Floyd County; 38 deaths from a population of 12,000 in Giles County; and 66 deaths in a population of 18,000 in Montgomery County, where Virginia Tech is located. In these communities, the deaths from influenza were significantly higher than usual numbers, but certainly awareness of the disease would have been different than the experiences of those living in large cities, where overcrowded hospitals, exhausted physicians, and unburied bodies have shaped the narrative of the disease (fig. 2).Footnote 11 As historians continue to research this topic, broadening the lens of analysis to include rural communities, especially in the southeastern and southwestern states, including those with broad demographic range, is essential to fully understand how people experienced this epidemic.

Figure 2. Library of Congress: “Her sister had not seen Mrs. Brown for almost a week, and with Mr. Brown a soldier in France, she became so worried she telephoned Red Cross Home Service which arrived just in time to rescue Mrs. Brown from the clutches of influenza, November 1918.”

Part II: Connections to the Present

CMN: As we move forward with our discussion, it seems like a good moment to culminate some of what we have already discussed to reflect on connections between the pandemic of 1918–19 and today.

TE: I share Nancy's sense that Covid-19 has been a humbling experience. After researching and teaching about the 1918 epidemic, and leading two summer seminars for K–12 teachers about this historical event, I could not have imagined the course of events in the United States and globally in the last four months. I had been aware, of course, of the predictions made by epidemiologists of global pandemics, of transmission from humans to animals, and of the limits of the health system to deal with catastrophic disease outbreaks. My awareness of these possibilities was tempered, however, by assertions, by experts, that the most likely widespread disease, influenza, could be managed with vaccines, therapeutics, and treatments; and second, that a more specific disease outbreak, which turned out to the coronavirus, was so unlikely and would be so limited in its scale that it could be safely contained. Both predictions, of course, turned out to be wrong; my faith in these predictions replicated assumptions that public health experts made early in the 1918 epidemic, when they predicted normal patterns for seasonal influenza, downplayed early reports of more severe cases, and proclaimed confidently that they could manage an infectious disease outbreak.

As I observed the course of Covid-19 during winter and spring 2020, I was constantly reminded of similar stages in 1918. The earliest reports of unusual disease patterns and higher mortality in Wuhan resembled the first reports in American newspapers of the diseases spreading through Europe, initially in Spain (hence the name, Spanish influenza) and then in Germany, France, and England. As the first cases appeared in the United States, I cautioned the public, in an article in the Washington Post, and my students, that the number of cases associated with this disease were vastly outnumbered by the deaths caused each year by seasonal flu.Footnote 12 As the number of deaths increased dramatically, particularly in New York and New Jersey, it felt very much like the weeks of peak weeks of the epidemic in October 1918 across the United States. Even the daily reports were similar: the number of cases and deaths; dire warnings from public health officials; painful stories of lives lost; heroic actions by health care workers; promises of a vaccine; and an eagerness for any sign that the number had plateaued and would start to decrease.

The most striking similarity was the introduction of measures such as closing schools, prohibiting public assemblies, restrictions on businesses, and recommendations regarding masks. Whereas early in Covid-19, the historical examples from 1918 appeared as a worst-case situation, after more than two months of social distancing, the response to Covid-19 has actually gone much further than was the case in 1918. As countries begin discussing how to reopen and considering long-term plans to manage social distancing, the relevance of 1918 may actually be diminishing, because the social distancing measures implemented to deal with influenza ended more quickly with almost no effort to restore them after winter 1919. In other areas, however, 1918 remains highly relevant, including these four areas: 1) recommendations and requirements to masks in public; 2) the quest for a vaccine; 3) the challenge of how to remember the victims of this disease outbreak; and 4) the imperative to learn from this epidemic and find new ways to deal with future outbreaks.

The most important lesson from 1918, as I observed each stage of the 2020 outbreak, is the importance of listening carefully, critically, and responsibly to advice from public health experts. As historians know very well, public health experts in 1918 failed to anticipate the scope of the disease, reassured the public with unjustified optimism, and pursued policies based on hope rather than evidence. Yet the advice and policies recommended in 1918 also contained the core of what was recommended in spring 2020: wash your hands, cover your cough, stay away from people, stay home when possible, and seek medical attention at the earliest sign of certain symptoms. As the scope and severity of the epidemic increased, in 1918 as in 2020, the warnings, exhortations, and demands scaled appropriately, and people responded by taking these instructions seriously. Any time I have been asked by students, colleagues, media, or the public about what lesson to take from 1918, my answer has been the same: think carefully about the advice coming from public health experts, understand the intent as well as the implications of these measures, and implement them as best you can, for your own health and, most importantly, for the health of the community. This message was present in 1918 and in 2020; the challenge is getting people to pay attention, modify their behavior, and be consistent in their actions.

NB: I am so grateful to others on the roundtable for the ways you are expanding my thinking, as both a scholar and a teacher, about the 1918 pandemic and resonances in 2020. Like Tom, I have been struck by how our patterns of response to Covid-19 have mirrored those of 1918. To those he has listed, which I would strongly second, I would add, in particular regarding the United States circumstances, the inadequacies of our federal response; the resultant emphasis on state and local public health and political leadership; the resultant scattershot approach to public health responses; and the appeal to martial metaphors to narrate and explain our experiences. I want to focus on three other areas of parallel.

Each of us has emphasized the importance of recognizing the victims of the 1918 pandemic in our teaching. What I have found so heartbreaking, and so crucial to highlight, is how fully in 2020 we have re-created the inequitable distribution of that suffering. In 1918, the poor entered the pandemic without the personal resources to protect them against the consequences of the loss of a single breadwinner, even for a short period. Hunger, cold, homelessness, the sending of children to work or to an orphanage, were all common consequences. While we don't have sufficiently reliable data from 1918 to be able to say definitively how race affected death rates, it is quite clear that the practices of white supremacy—both before and during the pandemic—enhanced still further the suffering among people of color. In 1915, while white Americans had an average life expectancy of 55.1 years, African Americans’ life expectancy was only 38.9 years, a shocking difference resulting from racism and the poverty and inequitable access to segregated health care it produced. The conditions that caused this disparity did not disappear during the pandemic, but were intensified. In some locales, for instance, African Americans were excluded from publicly funded emergency hospitals. Indigenous and immigrant communities suffered from cultural misunderstandings and condescension as public health officers or charity workers intervened in their households. In 2020, though legal segregation is gone, we are seeing the disparate landing of this pandemic following the same patterns of the earlier pandemic, with people of color, especially African Americans, Latinx Americans, Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, and Pacific Islanders in our communities suffering hospitalization and death at rates far above those of white Americans. The economic consequences of the pandemic, too, are landing inequitably on the poor with desperate consequences for millions of families and nevertheless an inadequate response of support from the federal government. This same scenario is playing out globally as well, as communities and nations lacking basic resources and access to inadequate health care are reeling from the pandemic.

The failure of presidential leadership in the United States—another parallel between the two pandemics—has only exacerbated these problems. Woodrow Wilson allowed the Fourth Liberty Loan drive to go forward and did not halt troop movements, both facilitating the spread of the disease. Perhaps most shocking, he never addressed the American people publicly about the pandemic, offering neither guidance nor sympathy. President Trump has offered repeated commentary on the pandemic, but much of it has been misguided or divisive. He has confused public understandings with his frequent misinformation and politicized basic public health protections and practices with his refusal to wear a mask and his tweets calling for the liberation of states under stay-at-home orders.

One of the president's many misstatements has been his repeated claim that the nation was well prepared for, and successfully handling, the pandemic. In 1918, too, Americans were overly optimistic and inadequately prepared, and as a result were shocked by the pandemic and the chaos and suffering it unleashed. Some of this was due to the nature of this particular strain of influenza—the pace of its spread across the country and the world, the speed with which individuals might sicken and die, its unusually high mortality rates, particularly among young adults, and the horrific impact of its symptoms. But Americans were also surprised because they had embraced the optimism of public health and medical professionals. With the bacteriological revolution Joseph Gabriel mentioned earlier, scientists had discovered the causal agent for a range of diseases that had long tormented Americans, from dysentery, malaria, and scarlet fever to typhoid, yellow fever, and whooping cough. They imagined containing these diseases, and even finding cures for them. As the pandemic raged through Europe in the summer of 1918, many in the United States, including public health leaders, offered optimistic pronouncements about Americans’ ability to dodge the disease that was sickening other nations. Even when influenza was coursing across the eastern states, western leaders repeatedly suggested their community might avoid the scourge because of their particular advantages in environment or health. This optimism worked against preparedness. In 2020 the United States has exhibited a similar hubris, again born of a combination of beliefs in American exceptionalism and the capacity of science and technology to protect us. Failing to take preparedness seriously is not a fault only of the current president, but reaches back to 9/11, and even earlier to efforts to downsize the federal government, and is evident at state, local, and individual levels as well.

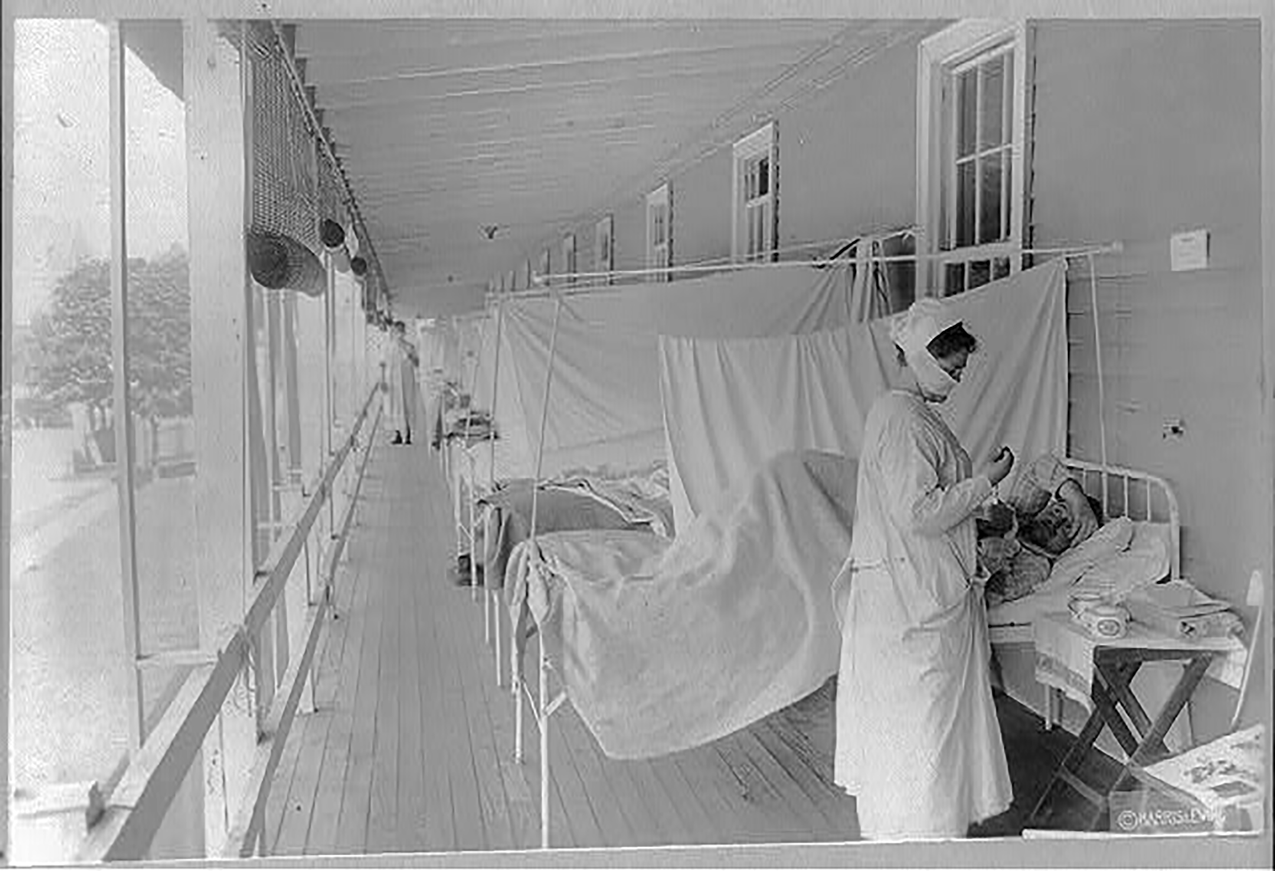

As I mentioned in my first response, I look at pandemics as moments that help us see a nation, a community, a culture, a society, a people, more clearly, as their practices and principles are often exposed starkly in the midst of the catastrophe. Given their persistence in 2020, I will continue to encourage students studying the 1918 pandemic to take a close look at the problems of poverty and white supremacy amidst the shared catastrophe and at the ongoing need for federal leadership and a preparedness system that do not rely on the president but rather on experts in public health, medical research, and health care provision (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Library of Congress: “Influenza ward, Walter Reed Hospital, Washington, D.C. [Nurse taking patient's pulse], c. November 1, 1918.”

EO: The COVID-19 pandemic has made me see in greater clarity the ways disease outbreaks both highlight and amplify a culture's existing inequalities. Diseases may enter bodies already preyed upon by the impacts of racism, sexism, poverty, violence, and other forces, and while these issues played out differently in 1918 and 2020, they still underlie each outbreak. For me, COVID-19 also exposes how events or trends we tend to conceptualize as distinct—wars, revolutions, political regimes, medical advances, pandemics, and much more—even as we work to contextualize them, are in fact vast intersecting networks made up of multiple human and nonhuman actors, as Bruno Latour might remind us.

As I write this in June of 2020, I know by the time this roundtable is published that key issues and the COVID-19 story will likely have radically shifted again (and again). So, I want to add a caveat that comparisons between the two pandemics at this stage may be premature and subject to great change. I am currently haunted by the possibility that the worst wave of COVID-19 is yet to come, and that the outbreak might follow the 1918 pattern, with a far deadlier second wave hitting between September and December. Will that happen? Or is the worst over? Making decisions assuming that the past is prologue and a second wave is coming, or assuming that this outbreak is nearing its end, could both prove dangerously wrong. As folks above have observed, we don't yet know where we are in our story.

One aspect of both outbreaks, though, is helping me think through some of the differences and overlaps between the two pandemics, as well as showcasing how intertwined discrete events and factors are: the crowds that gathered (and are gathering) in some areas in the midst of each pandemic, and how we might consider the complexities of these crowds.

During the influenza pandemic's deadly second wave, the First World War ended, and people in many countries turned out in large numbers to celebrate the armistice. Doctors and health care officials raised the alarm about these gatherings, asking people to please avoid crowding into trams and joining parades. The literature of the time repeatedly notes the interactions of the armistice celebrations with the pandemic, with characters hearing the bells for armistice from sickrooms and crowded hospitals, and funeral processions for flu victims literally running into end-of-war parades. Indeed, the French filmmaker Abel Gance and his assistant director Blaise Cendrars were walking in the funeral cortege for the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (dead from influenza) when it hit a parade of revelers celebrating armistice; they added a scene to memorialize this experience in Gance's famous anti-war film J'Accuse. One can understand the need to celebrate the end of the most brutal war the world had seen up to that point, a mass death event unprecedented in human history. In the weeks after these crowded celebrations, death and infection rates from influenza predictably soared in many areas. The war and the pandemic were already intertwined: the war had greatly hastened the spread the virus, and the outbreak had changed military strategy and the outcome of battles; armistice celebrations further spread the virus—but they were not necessary to stop the war.

COVID-19's interactions with the current marches against police brutality and racism offer a distinctly different set of circumstances, even as the crowds might also spread a virus. In the United States and in other countries right now, large groups are gathering to protest long-standing problems with police violence particularly against black populations, as well as systemic and systematic racism. As many commentators have pointed out, these problems represent a deadly pandemic in themselves that has unfolded year after year and decade after decade. At the same time, we have seen the way COVID has highlighted inequalities in health care access and outcomes, and the ways decades (and centuries) of racist policies in employment opportunities, housing, education, and more have contributed to these disparities.

As even epidemiologists and WHO have recognized, the risks of such protests in the midst of the pandemic are outweighed by the importance and deadliness of the issues represented by those very protests; the experts continue, though, to urge the importance of masks, distancing, outside events, hand sanitizer, and other steps, and they highlight the dangers of using tear gas—designed to produce heavy bouts of coughing—by police in the midst of a pandemic spread by respiratory droplets.

The art that arises in the United States from this period will need to find ways to represent the complex interactions of the COVID crisis with the protests and all the issues both represent.

JG: One of the ways that the Covid-19 pandemic has affected my work is that it has reminded me that historians and other scholars can conduct research that connects the past to the present in ways that go beyond the framework of providing “context” or “lessons from the past.” Like most historians, I tend to focus my scholarly efforts on research that engages with other historians, and of course I hope that at least some of my work reaches a broader reading public. The current situation, however, reminds me that as scholars we have a perspective and a set of skills that can actually be integrated into multidisciplinary research projects in a very practical, concrete way. This is something I learned from Howard Kushner, who until recently taught at Emory. Kushner regularly advocated for what he called “the applied history of medicine,” which for him meant integrating historians into multidisciplinary public health and biomedical research teams. Kirsten Ostherr at Rice has recently made a similar argument by calling for the humanities to be a part of the pandemic response “through immediate, translational, front-line work.”Footnote 13 Ostherr argues that scholars in the medical humanities—including historians—can play an essential role in the response to COVID-19 by bring their expertise to bear in the construction and analysis of narratives that connect human behavior and data about disease. To take one example, in 2006, researchers affiliated with the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan were asked by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control to study non-pharmaceutical responses to the 1918 pandemic. They combined historical and statistical methods to demonstrate that early implementation of mitigation efforts in cities lowered mortality associated with the outbreak. They then published their results in the Journal of the American Medical Association and, along with the results of a handful of similar projects, their analysis became the basis for the CDC's pandemic response guidelines.Footnote 14 I don't think it is too much of a stretch to say that we are all living with the results of their work. This is a really powerful example of how historical scholarship can very much be an applied endeavor.

At the same time, though, from my perspective one of the most important connections between 1918 and today is the ongoing process through which novel viruses emerge and our failure to adequately prepare for the concomitant threat to public health. I think it is really important for people—including our students—to understand that the 1918 pandemic was a particularly horrible example of a process that, in many ways, appears to be getting worse rather than better due to globalization; environmental destruction; the development of industrial agriculture; and other large, structural changes to our economy and society. I think that as historians we could be doing a lot better in terms of connecting the dots between these things and explaining the really profound threat that novel viruses represent, including both novel strains of influenza and coronaviruses. I haven't fully thought this through, but it may be the case that the focus on the 1918 pandemic as “forgotten” actually reinforces this tendency in subtle ways. After all, even though the broader public may have stopped talking about the 1918 pandemic soon after it took place, public health authorities, virologists, and other relevant scientific communities did not. They have been thinking about the 1918 pandemic ever since. Yet the ability of the public health infrastructure in the United States to respond to another catastrophic event has been significantly eroded over the last three or four decades for what I think are primarily ideological reasons. We are obviously living with the consequences of this reduced ability right now, and I don't think the fact that the 1918 pandemic somehow got written out of our historical memory is coincidental. So, I think it is worth asking ourselves whether the 1918 pandemic was in fact “forgotten” or whether knowledge about it was in an important sense intentionally erased or limited to certain communities of researchers and experts. This gets into a complicated discussion about the differences between forgetting, the intentional creation of ignorance, and related topics that historians and philosophers of science have recently begun to explore through the framework of agnotology, or the study of socially induced ignorance. We need to talk about the 1918 pandemic in terms of our current failure to adequately conceptualize and prepare for what is coming down the pike.

Outside of this, my biggest concern about the way that narratives of the 1918 pandemic have been deployed during the current crisis is how they have tended to replicate the simple message that we should all follow the recommendations of public health authorities without making much of an effort to describe why so many people don't. I think everyone in this roundtable agrees that we should follow public health recommendations to the extent that we can. But a lot of people don't agree with us. And a lot of people may agree with us but be unable to do so, for a wide variety of reasons. Unfortunately, in my view, we often describe people who reject the authority of physicians and public health experts as irrational or in other uncharitable ways. This doesn't do anyone any good and, in fact, can actually make the problem worse. It really is a problem that both public health authorities and clinicians make recommendations that people either can't or won't follow, and one of the things that historians can contribute in this area is a deeper and more subtle understanding of why people often reject the authority of medical and public health experts—not so that we can get people to do what we want them to do, but so that we can craft our interventions to better meet their needs. Judith Leavitt, Robert Johnston, and others have done important work on this issue as it relates to the Mary Mallon case, antivaccinationism, and related topics, but the tension between scientific authority and popular resistance to its implementation is a general dynamic that as scholars we could really do better on. Simply pointing to the 1918 pandemic and saying that it shows that we should all be following public health recommendations isn't really adequate, at least not in my view. We need to understand why people don't believe us when we make these kinds of assertions. And part of this is understanding and being honest about the messy, contested, and sometimes arbitrary nature of scientific practice and authority.

BM: Pandemics and Pandemonium: I see the pandemic changing my teaching in how I address public health problems in poor countries. It was only during the last fall semester (2019) that I was discussing with my history majors the latest Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where corrupt governance, poverty, and sharp ethnic conflict are the norm. Not coincidentally, the provinces of the DRC most affected by the outbreak were those same areas that have been at the center of civil unrest since the 1990s. At the time, October 2019, my class discussed in amazement how and why local communities looked with suspicion upon nonprofit groups like Doctors Without Borders. Many Congolese refused to believe the outbreak was real, and that recommended treatment was a hoax to poison people. It is striking how Covid-19 has revealed American versions of public hysteria comparable to that seen in parts of the DRC facing Ebola.

Moving forward, as I continue to teach about the influenza of 1918 as well as start to integrate discussions of Covid-19 into my classrooms, I want to give more consideration to the social and cultural factors that problematize attempts to mitigate pandemics. How could Congolese not take Ebola seriously? Why would many Congolese deny help and treatment? Why would some Congolese bring violence upon treatment centers? These questions from my students in fall 2019 eerily parallel questions we have in the present about why many Americans spurn public health experts’ protocols and warnings about Covid-19. Why do some Americans not socially distance? Why do some Americans insist on reopening businesses despite rising numbers of cases? Why do some Americans roll their eyes at the idea of wearing masks in public? Clearly, pandemics are more than just health crises. They produce concerns about the mentality of a nation as much as they do about the microbes of the people.

Pandemics, coming to a country near you: As we think about what lessons the influenza outbreak of 1918 holds for us dealing with Covid-19 in 2020, it is important to acknowledge that pandemics will likely affect underdeveloped and poorer nations worse than developed nations. Like Mexico of a century ago, Syria's civil war is nearly a decade old; the economy is in ruins, hundreds of thousands of people have been killed; millions more have been displaced. Also, like the Mexican Revolution, foreign intervention has played an indelible part in Syria's civil war. Why should this concern us? Why is it important? For the reason that one nation's problems can easily become the problems of another nation, or an entire region of nations. When we look around the world at countries in crisis, we should consider how their internal problems (e.g., revolutions), one, are breeding grounds for the pandemic but also, two, how the interconnectedness of our globalized world can magnify the problem of pandemics. Immigration is one of the most indelible features of globalization.

We commonly view immigration as a choice. Immigrants are dissatisfied with their lot in their home country and so they make the decision to go to another country. For many persons, however, immigration is less a choice than an escape from exploitation and even violence.

It was not until after World War II that the community of nations realized that persons forced to leave their home countries because of violence and poverty were not really immigrants but rather refugees. A formal definition for refugees was codified in 1951 and has been accentuated since.Footnote 15 In the decades after World War II, however, the definition of refugees was increasingly inadequate as the world was “teeming” with millions of refugees because of war, revolution, and famines.Footnote 16 What responsibilities, it was asked by world leaders, did the global community have to a person who was a refugee not because of their religion or political affiliation, but rather because of the poor structural problems and violence in their home countries? This lack of clarity played a part in refugee-receiving nations such as the United States gradually closing the legal entryways for displaced peoples. As international responsibility toward the welfare of refugees withered, nativist prejudice toward immigrants proliferated during the last decades of the twentieth century.

The ways in which European politics have changed in response to the Syrian refugee crisis has been well documented. What is new for us to consider in this time of Covid-19 is how fears of pandemic graft onto anxieties about immigrants. Here we will look back to history to provide an answer for the present. Even though they were not deemed as such the hundreds of thousands of Mexicans who crossed into the United States during Mexico's Revolution of 1910–1920—like Syrians crossing into Europe since 2011—were essentially refugees. During the flu pandemic, nativism and public health concerns worked in tandem at the U.S.-Mexican border, demonstrating how public health could and was used as a tool of racial prejudice and a justification for immigration restriction.

Influenza came to the United States not only within a context of war but also at a time of rapidly changing immigration law. The Immigration Act of 1917 was the first action by the U.S. Congress in almost forty years to place substantive restrictions on immigration to the United States.Footnote 17 Its two most notable features were to bar all illiterate immigrants from entering the United States and a measure to completely disallow Asian immigration. In the coming years, 1921 and 1924, U.S. immigration law would become even stricter as quotas were placed on European immigration, with the prime objective to curtail what was considered undesirable immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. Ironically, in this context of war and hardening immigration policies, rates of European immigration to the United States plummeted, by over 90 percent between 1914 and 1918 (from 1,218,480 to 110,618).Footnote 18 Within this void, Mexican immigration came under more scrutiny. And that increased Mexican immigration was driven in no small part by the influenza outbreak of 1918–19.

Anti-immigrant sentiment—nativism—runs deep in U.S. history. For many Americans, immigrants were a foreign threat. Immigrants’ foreignness was rooted not just in different cultural mores and social norms, but also in the microbes that immigrants allegedly brought into the United States. One of the most durable words used by nativists to describe what they viewed as the immigrant threat was invasion. Immigrants invaded the nation economically (labor competition), politically (socialism, anarchism, communism), socially (religion), and biologically (disease). Immigrants were, to use Elizabeth's terminology, scapegoated.

Among its features already mentioned, the 1917 Immigration Act also established a medical examination process by which immigrants were determined health risks to the American people. During the flu pandemic, the fear for public health directly fused with a nativist view of immigrants as diseased persons. One tangible way in which this fear for public health combined with a conception of foreigners as diseased was in border inspections at crossings such as in El Paso, Texas. A process of separating those who were “desirable” from the “undesirable” immigrants was with border inspectors using subjective exams to separate “first class” passengers—those who looked well to do and educated—from those “second class” migrants (the concept of steerage passengers borrowed from ocean travel). While first class passengers were exempted from medical exams, second class passengers, most of whom would have been Mexican migrants, who came to El Paso after 1917 were subjected to delousing baths. These baths were a humiliating process: migrants were forced to remove their clothes and bathe while their clothes were washed and dried. It was easy to distinguish people who had recently crossed the border because their clothes were often wrinkled after the delousing process. Migrants compared the experience to being treated like animals who “were bringing germs.” Hoping to persuade border officials to waive the delousing requirement, some migrants tried to avoid the humiliation of these baths by taking care to be clean and well dressed as they arrived at the border crossing.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, as one migrant would recount, “it did me no good to tell them [border agents] that I had taken a bath a few minutes before in [Ciudad] Juarez,” he was subjected to a bath anyway. Clearly, the nativist fear of Mexicans ran deeper than the public health risk posed by migrants.Footnote 20

Even as the flu dissipated by spring 1919, a new, invasive threat seemed to loom for Americans: Communism. For Americans who had suffered from a fever that had made them irrational,Footnote 21 it was not a coincidence that the great majority of socialist and communist subversives identified by the U.S. Justice Department during the (First) Red Scare were Russian and German immigrants.

As we consider the politics of the pandemic, we need to notice how the fever of panic and prejudice spreads. In U.S. history, the fear of invasion is deeply imbued with the fear of immigrants. Xenophobia underlined the resurgent isolationist/unilateralist spirit of American politics after the late 1910s. It was an isolationism that undermined global security concerns as it spurned foreign peoples. The first step toward ameliorating Americans’ xenophobic, isolationist tendencies in the present is to test the paranoia that underlines American nativism, track all the ways xenophobia crops up in public rhetoric, and trust that our lessons from the past do not predetermine our future responses to issues such as global pandemics.

Part III: Expanding the Frame: Teaching, Presenting, and Commenting

CMN: Ben's comments present an advantageous way to draw together a number of strands of our conversation and segue into our final focus on teaching. Since we all teach aspects of the pandemic of 1918–19, I wanted to tap your expertise. As for me, I always begin my U.S. history survey class, which covers the 1910s to the present, with the pandemic. Never has it been so interesting to my students and the obvious relevance led to a dynamic discussion and to a spate of optional writing assignments in a way that I have not seen in my time as a professor in teaching required lower-level classes. So, with that in mind, I'd like to ask two connected questions: What do you think the pandemic offers for the classroom? What are some specific best practices, techniques, and resources you might recommend for those who want to learn or are now hoping to teach the pandemic in their courses?

TE: The 1918 influenza epidemic provides historians and history students with a remarkable opportunity to observe the process of how societies make sense of an unexpected disease outbreak. My research and teaching have focused on the ways that three types of primary sources reveal this process before, during, and after the epidemic: newspapers, medical journals, and health department reports. These sources address many of the key themes identified in this roundtable, yet they also suggest other themes that provide insights into public opinion, expert knowledge, and social impact. Interpreting these sources requires careful attention to omissions, biases, and priorities, but these patterns themselves are essential to understand the epidemic. For students, doing research on the 1918 influenza epidemic is a remarkable way to explore contemporary responses to the outbreak, to learn the skills needed for historical analysis, and then develop empathy as part of historical understanding.

Digitized newspapers allow students to explore local responses to the epidemic within particular cities and communities. A search for keyword “influenza” or “epidemic” in the Library of Congress Chronicling America collection produces more than 40,000 results for just the months from September to December 1918, including more than 6,000 front pages of newspapers. Research by students in my class revealed that some newspapers included coverage of the influenza on every front page during the peak month of the epidemic, October 1918. The scale of this coverage clearly refutes the claim made by some historians, and repeated in popular reporting, that news about the epidemic was either suppressed or censored. The more challenging research and teaching question, therefore, is to ask what the newspaper coverage reveals about popular understanding of the disease, how newspapers served to mediate between expert advice and public responses, and how different kinds of content (news articles, editorials, public health statements, advertisements, leisure columns, and even sports section) reported on the disease at the national, regional, and local levels. In addition to providing a substantive basis for writing a narrative of the disease, we used a model suggested by the open access Influenza Encyclopedia to think about how newspapers can also help us explore critical questions about the influenza, including the differential impact on various populations, the tension in public health statements between raising awareness, stoking fear, and encouraging complacency; the important local and regional variations in the impact of the epidemic; and especially the opportunity to tell the story of the epidemic using individual stories of victims, health care workers, and other community members. Using newspapers to research and teach about the 1918 influenza epidemic is complicated, unfortunately, by inconsistencies in newspaper collections, especially given that so many titles are available only in subscription databases.

CMN: In addition to thinking about teaching and resources, as Tom just did, I also wanted to ask how you have approached doing public commentary regarding the pandemic of 1918–19 given the remarkable relevance of the topic and the pressure to explain the “lessons” of the past that we might apply today.

NB: The 1918 influenza pandemic is an extraordinarily rich subject for teaching. As this roundtable has illuminated, it invites the use of the widest range of methodologies across the discipline of history. It encourages as well cross-disciplinary and interdisciplinary explorations as Elizabeth has made clear. Above all, it is a subject of importance around the globe, both in particular nations and also, as Ben has illustrated, transnationally. This means that teachers can approach influenza from the space they most comfortably occupy as a pedagogue, gaining a foothold there. In my case, then, I focus especially on the social history of the pandemic, but I also attempt to reach across methodologies and beyond the field of history, because this provides access routes for a diversity of students with their varied preoccupations and passions. Science students might feel invited in if a course touches on the hunt for the virus, while a student with interest in English might find their footing with the exploration of the literary output of the aftermath, and a student in African American Studies might want to learn more about how black newspapers covered the pandemic. This is not to suggest that students should only study that which is familiar, but rather the opposite: that once a student finds a place for themselves in the subject, they will likely be intrigued as well by other aspects of a unit or course that focuses on the pandemic.